Democracy is the theory that two thieves will steal less than one, and three less than two, and four less than three, and so on ad infinitum.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

A Little Book in C Major, ch. 5, § 25 (1916)

(Source)

Variant:

DEMOCRACY. The theory that two thieves will steal less than one, and three less than two, and four less than three, and so on ad infinitum.

A Book of Burlesques, "The Jazz Webster" (1924)

Quotations about:

theft

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Sometimes when a person sees the roguery of poor people and the thievery of people in high positions, he is tempted to regard society as a forest full of robbers, the most dangerous of which are the policemen that are set up to stop the others.

[En voyant quelquefois les friponneries des petits et les brigandages des hommes en place, on est tenté de regarder la société comme un bois rempli de voleurs, dont les plus dangereux sont les archers, préposés pour arrêter les autres.]

Nicolas Chamfort (1741-1794) French writer, epigrammist (b. Nicolas-Sébastien Roch)

Products of Perfected Civilization [Produits de la Civilisation Perfectionée], Part 1 “Maxims and Thoughts [Maximes et Pensées],” ch. 3, ¶ 198 (1795) [tr. Siniscalchi (1994)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

Seeing the rogueries of little men and the extortions of the great in office, one is tempted to look upon Society as a wood infested by robbers, the most dangerous being the constables sent to arrest the others.

[tr. Mathers (1926)]

At times, seeing the petty thieveries of the petty, and the robberies of those in office, one is tempted to regard society as a wood full of thieves, of which the most dangerous are the officers set there to arrest the others.

[tr. Merwin (1969)]

Sometimes, when one observes the rogueries perpetuated by petty people and the graft committed by men in office, one is tempted to think of society as a wood infested by thieves, of which the most dangerous are the archers, posted to prevent the others from escaping.

[tr. Pearson (1973)]

There are times when, seeing the nasty tricks people get up to, the gross frauds of high officers, you're tempted to think that you're in a wood infested by thieves, amongst whom the most dangerous are the police, whose purpose is supposed to be that of arresting them.

[tr. Parmée (2003), ¶ 152]

A poor man defended himself when charged with stealing food to appease the cravings of hunger, saying, the cries of the stomach silenced those of the conscience.

Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington (1789-1849) Irish novelist [Lady Blessington, b. Margaret Power]

(Attributed)

(Source)

Quoted, without citation, in R. R. Madden, The Literary Life and Correspondence of the Countess of Blessington, Vol. 1 (1855).

To have and not give is in some cases worse than stealing.

[Haben und nichts geben, ist in manchen Fällen schlechter als stehlen.]

Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830-1916) Austrian writer

Aphorisms [Aphorismen], No. 41 (1880-1893) [tr. Wister (1882)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:

To have and not give is in some instances worse than stealing.

[tr. Scrase/Mieder (1994)]

Every man is bound to bear his own misfortunes rather than to get quit of them by wronging his neighbour.

[Suum cuique incommodum ferendum est potius quam de alterius commodis detrahendum.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 3, ch. 5 (3.5) / sec. 30 (44 BC) [tr. Cockman (1699)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translation:

Every man ought to bear his own evils, rather than wrong another, by stripping him of his comforts.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]

It is rather the duty of each to bear his own misfortune, than wrongfully to take from the comforts of others.

[tr. Edmonds (1865)]

Each man must bear his own privations rather than take what belongs to another.

[tr. Peabody (1883)]

A man should bear his own misfortune rather than trench upon the good fortune of another.

[tr. Gardiner (1899)]

It is the duty of each man to bear his own discomforts, rather than diminish the comforts of his neighbor.

[ed. Harbottle (1906)]

Each one must bear his own burden of distress rather than rob a neighbour of his rights.

[tr. Miller (1913)]

Each man should endure his own suffering rather than reduce the benefits of another person.

[tr. Edinger (1974)]

For that is an absurd position which is taken by some people, who say that they will not rob a parent or a brother for their own gain, but that their relation to the rest of their fellow-citizens is quite another thing. Such people contend in essence that they are bound to their fellow-citizens by no mutual obligations, social ties, or common interests. This attitude demolishes the whole structure of civil society.

[Nam illud quidem absurdum est, quod quidam dicunt, parenti se aut fratri nihil detracturos sui commodi causa, aliam rationem esse civium reliquorum. Hi sibi nihil iuris, nullam societatem communis utilitatis causa statuunt esse cum civibus, quae sententia omnem societatem distrahit civitatis.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 3, ch. 6 (3.6) / sec. 28 (44 BC) [tr. Miller (1913)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translation:

For as to what is usually said by some men, that they would not take anything away from a father or brother for their own advantage, but that there is not the same reason for their ordinary citizens, it is foolish and absurd: for they thrust themselves out from partaking of any privileges, and from joining in common with the rest of their citizens, for the public good; an opinion that strikes at the very root and foundation of all civil societies.

[tr. Cockman (1699)]

That indeed is absurd, which some men avow, that for their own advantage they would take nothing from a parent or a brother; but that the case of other citizens is different. These men, stablish with their fellow-citizens no common right, no society for common advantage; an opinion that unhinges the whole internal intercourse of a state.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]

For that which some say, that they would take nothing wrongfully, for the sake of their own advantage, from a parent or brother, but that the case is different with other citizens, is indeed absurd. These establish the principle that they have nothing in the way of right, no society with their fellow citizens, for the sake fo the common interest -- an option which tears asunder the whole social compact.

[tr. Edmonds (1865)]

For this is absurd indeed which some say, that they would take nothing from a parent or a brother for their own benefit, but that it is quite another thing with persons outside of one’s own family. These men disclaim all mutual right and partnership with their fellow-citizens for the common benefit, -- a state of feeling which dismembers the fellowship of the community.

[tr. Peabody (1883)]

It is absurd for people to say that they will not despoil a father or a brother for their own advantage but that fellow-citizens stand on quite a different footing. That is practically to assert that they are bound to their fellow-citizens neither by mutual obligations, social ties, nor common interests. But such a theory tears in pieces the whole fabric of civil society.

[tr. Gardiner (1899)]

The contention that some people advance is absurd, of course: they argue that they would not deprive a parent or brother of anything for their own advantage but that there is another standard applicable to all other citizens. These people do not submit themselves to any law or to any obligation to cooperate with fellow citizens for the common benefit. Their attitude destroys any cooperation within the city.

[tr. Edinger (1974)]

If fifty bands of men surrounded us

and every sword sang for your blood,

you could make off still with their cows and sheep.[εἴ περ πεντήκοντα λόχοι μερόπων ἀνθρώπων

νῶϊ περισταῖεν, κτεῖναι μεμαῶτες Ἄρηϊ,

καί κεν τῶν ἐλάσαιο βόας καὶ ἴφια μῆλα.]Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Odyssey [Ὀδύσσεια], Book 20, l. 49ff (20.49) [Athena to Odysseus] (c. 700 BC) [tr. Fitzgerald (1961)]

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:

If there were

Of divers-languag’d men an army here

Of fifty companies, all driving hence

Thy sheep and oxen, and with violence

Offer’d to charge us, and besiege us round,

Thou shouldst their prey reprise, and them confound.

[tr. Chapman (1616)]

Though fifty bands of men should us oppose,

You should their herds of cattle drive away.

[tr. Hobbes (1675), l. 37ff]

Were we hemm’d around

By fifty troops of shouting warriors bent

To slay thee, thou should’st yet securely drive

The flocks away and cattle of them all.

[tr. Cowper (1792), l. 54ff]

Though fifty bands stood threatening thee and me,

All breathing slaughter, their fat kine and sheep

Thou shouldst drive off, and take their wealth in fee.

[tr. Worsley (1861), st. 6]

If fifty troops of men, as good as thou

Surround us twain, and strive to slay in battle,

Of their fat kine and sheep should'st thou be captor!

[tr. Bigge-Wither (1869)]

Though fifty bands of mortals that in speech

Articulate use their tongues around us rose

In conflict fierce to kill us both intent,

Still should'st though prove the man that all those beeves

And fatten'd flocks should to thye homestall drive.

[tr. Musgrave (1869), l. 70ff]

Even should fifty companies of mortal men compass us about eager to slay us in battle, even their kine shouldst thou drive off and their brave flocks.

[tr. Butcher/Lang (1879)]

If fifty bands of menfolk, word-speaking wights that are,

Stood round about us, eager for our slaying in the war,

Yet their kine shouldst though be driving and their goodly fatted sheep.

[tr. Morris (1887)]

Should fifty troops of mortal men stand round about us, eager in the fight to slay, you still might drive them away from their oxen and sturdy sheep.

[tr. Palmer (1891)]

Even though there were fifty bands of men surrounding us and eager to kill us, you should take all their sheep and cattle, and drive them away with you.

[tr. Butler (1898)]

If fifty troops of mortal men should stand about us, eager to slay us in battle, even their cattle and goodly sheep shouldest thou drive off.

[tr. Murray (1919)]

Though fifty troops of humans hemmed us round, all mad to kill outright, yet shuld you win through to lift their flocks and herds.

[tr. Lawrence (1932)]

If you and I were surrounded by fifty companies of men-at-arms, all thirsting for your blood, you could drive away their cows and sheep beneath their very noses.

[tr. Rieu (1946)]

Even though there were fifty battalions of mortal people

standing around us, furious to kill in the spirit of battle,

even so you could drive away their cattle and fat sheep.

[tr. Lattimore (1965)]

Even if fifty bands of mortal fighters

closed around us, hot to kill us off in battle,

still you could drive away their herds and sleek flocks!

[tr. Fagles (1996)]

Even if there were fifty squadrons of armed men

All around us, doing their mortal best to kill us,

You would still be able to run off with their cattle!

[tr. Lombardo (2000)]

If in fact there were fifty battalions of men who are mortal

Standing around us, eagerly striving to kill us in battle,

even from them you would drive their cattle away and their fat sheep.

[tr. Merrill (2002)]

You and I could be surrounded by fifty companies of men-at-arms, all thirsting for our blood, but you would still drive away their cows and sheep.

[tr. DCH Rieu (2002)]

If we were ambushed, surrounded by not one but fifty gangs of men who hoped to murder us -- you would escape, and even poach their sheep and cows.

[tr. Wilson (2017)]

If there were fifty troops of mortal men in ambush all around us, firmly determined to kill us, nevertheless even then you'd drive off their cattle and fattened sheep.

[tr. Green (2018)]

Even were fifty troops around us, to kill us, you'd end by driving off their cattle!

[tr. Green (2018), summary]

If there were fifty groups

of other men standing here around us,

intent on slaughter, even so, I say,

you’d still drive off their cattle and fine sheep.

[tr. Johnston (2019), l. 55ff]

Not to oversee Workmen, is to leave them your Purse open.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard’s Almanack (Nov 1751)

(Source)

Stealing, of course, is a crime, and a very impolite thing to do. But like most impolite things, it is excusable under certain circumstances. Stealing is not excusable if, for instance, you are in a museum and you decide that a certain painting would look better in your house, and you simply grab the painting and take it there. But if you were very, very hungry, and you had no way of obtaining money, it might be excusable to grab the painting, take it to your house, and eat it.

I took such pains not to keep my money in the house, but to put it out of the reach of burglars by buying stock, and had no guess that I was putting it into the hands of these very burglars now grown wiser and standing dressed as Railway Directors.

A real writer learns from earlier writers the way a boy learns from an apple orchard — by stealing what he has a taste for and can carry off.

Archibald MacLeish (1892–1982) American poet, writer, statesman

In Charles Poore, “Mr. MacLeish and the Disenchantmentarians,” The New York Times (25 Jan 1968)

(Source)

When the rich rob the poor it’s called business. When the poor fight back it’s called violence.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

(Spurious)

Frequently, but incorrectly attributed to Twain, no earlier than 2015. It appears to have been an anonymous phrase coined in the Occupy Movement in 2011. See here for more information.

[The] “robbing of the poor because he is poor,” is especially the mercantile form of theft, consisting in taking advantage of a man’s necessities in order to obtain his labor or property at a reduced price. The ordinary highwayman’s opposite form of robbery — of the rich, because he is rich — does not appear to occur so often to the old merchant’s mind; probably because, being less profitable and more dangerous than the robbery of the poor, it is rarely practice by persons of discretion.

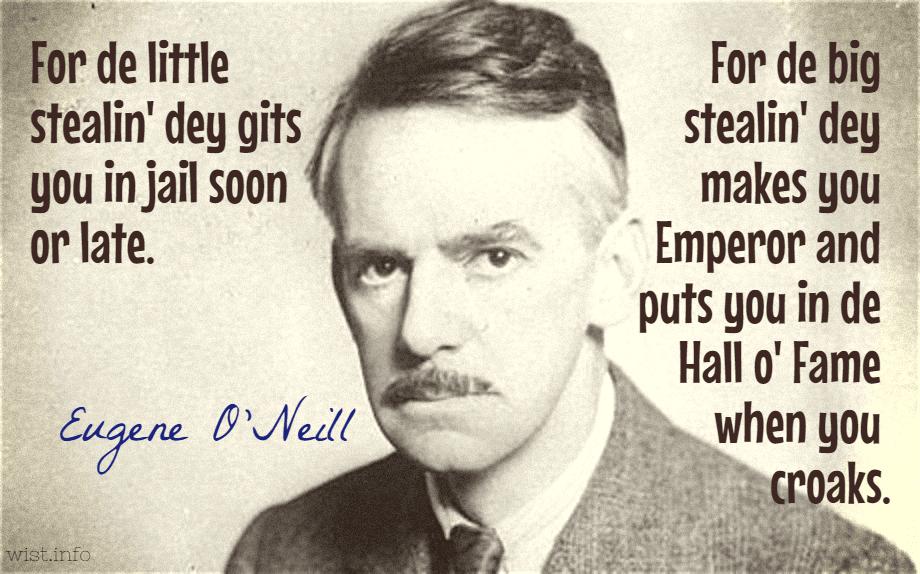

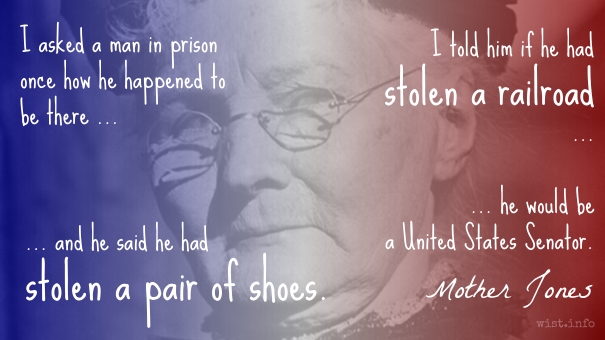

I asked a man in prison once how he happened to be there and he said he had stolen a pair of shoes. I told him if he had stolen a railroad he would be a United States Senator.

If you attempt to beat a man down and to get his goods for less than a fair price, you are attempting to commit burglary, as much as though you broke into his shop to take the things without paying for them. There is cheating on both sides of the counter and generally less behind it than before it.

I am convinced that every boy, in his heart, would rather steal second base than an automobile.

Tom C. Clark (1899-1977) American lawyer, US Attorney General, US Supreme Court Justice (1949-1967)

(Attributed)

Speaking of recreational programs to reduce juvenile delinquency. Quoted in Reader's Digest, Vol. 60 (1952). Restated as "I still believe that any boy would rather steal second base than an automobile" in Washington World, Vol. 3 (1963).

Accepting praize that iz not our due iz not mutch better than tew be a receiver of stolen goods.

[Accepting praise that is not our due is not much better than to be a receiver of stolen goods.]

Still, I do not mean to find fault with the accumulation of property, provided it hurts nobody, but unjust acquisition of it is always to be avoided.

[Nec vero rei familiaris amplificatio nemini nocens vituperanda est, sed fugienda semper iniuria est.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 1, ch. 8 (1.8) / sec. 25 (44 BC) [tr. Miller (1913)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Not but that a moderate desire of riches, and bettering a man's estate, so long as it abstains from oppressing of others, is allowable enough; but a very great care ought always to be taken that we be not drawn to any injustice by it.

[tr. Cockman (1699)]

The enlargement of fortune is blameless, while no man suffers by its increase; but injury is forever to be avoided.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]

Nor indeed is the mere desire to improve one's private fortune, without injury to another, deserving of blame; but injustice must ever be avoided.

[tr. Edmonds (1865)]

Nor, indeed, is the increase of property, without harm to any one, to be blamed; but wrong-doing for the sake of gain is never to be tolerated.

[tr. Peabody (1883)]

Not that we have any fault to find with the innocent accumulation of property; it is the unjust acquisition of it of which we must beware.

[tr. Gardiner (1899)]

Of course, no one should criticize an increase in a family's estate that harms no one else, but it should never involve breaking the law.

[tr. Edinger (1974)]

Fear: A club used by priests, presidents, kings and policemen to keep the people from recovering stolen goods.

Elbert Hubbard (1856-1915) American writer, businessman, philosopher

The Roycroft Dictionary (1914)

(Source)