You there, reader, the over-solemn one,

Take a hike wherever — my verse is spun

Only for blithe, witty cognoscenti

“Up” for priapic jeux de spree aplenty

Or aroused by bells on harlot’s fingers.

He who in these randy pages lingers —

Though more stern than Curius or Fabricius

Soon gets tingly, and anon lubricious;

Then, lo, beneath a toga something pokes.

My little book’s salacious whims and jokes

Will lead even the chastest dames astray;

Taken with wine, my lines can make ’em bray!

Lucretia, more proper than whom none such,

Peeked between my covers, blushed very much,

And threw me down (but Brutus stood glowering).

Brutus, “Ciao!” — and back she’ll be devouring.[Qui gravis es nimium, potes hinc iam, lector, abire

Quo libet: urbanae scripsimus ista togae;

Iam mea Lampsacio lascivit pagina versu

Et Tartesiaca concrepat aera manu.

O quotiens rigida pulsabis pallia vena,

Sis gravior Curio Fabricioque licet!

Tu quoque nequitias nostri lususque libelli

Uda, puella, leges, sis Patavina licet.

Erubuit posuitque meum Lucretia librum,

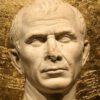

Sed coram Bruto; Brute, recede: leget.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 11, epigram 16 (11.16) (AD 96) [tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:To read my Booke the Virgin shie

May blush, (while Brutus standeth by:)

But when He's gone, read through what's write,

And never staine a cheeke for it.

[tr. Herrick (1658), "On his Booke"]Haste hence, morose remarker, haste:

Urbanity alone has taste.

No strains Lampsacian foul my page,

Nor feels my brass Tartessian rage.

yet here the mirth that cannot cloy,

Shall often shake thy sides with joy:

Suppose thy mind of graver mold,

Than Curius' self possest of old;

Or had thy features greater force,

Than his, that brav'd the solar course.

Nay thou my nonsense keen shalt read,

Meek made of Patavinian breed.

Lucretia blusht, and dropt the book;

Nor, Brutus there, would dain a look.

Brutus, begone: thy dame, at ease

Will show how my perusals please.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 3, ep. 64, "To the Morose"]Reader, if you are exceedingly staid, you may shut up my book whenever you please; I write now for the idlers of the city; my verses are devoted to the god of Lampsacus, and my hand shakes the castanet, as briskly as a dancing-girl of Cadiz. Oh! how often will you feel your desires aroused, even though you were more frigid than Curius and Fabricius. You too, young damsel, will read the gay and sportive sallies of my book not without emotion, even though you should be a native of Patavium. Lucretia blushes, and lays my book aside; but Brutus is present. Let Brutus retire, and she will read.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859). "To His Readers"]You, reader, who are too strait-laced, can now go away from here whither you will: I wrote these verses for the citizen of wit; now my page wantons in verse of Lampascus, and beats the timbrel with the hand of a figurante of Tartessus. Oh, how often will you with your ardour disarrange your garb, though you may be more strait-laced than Curius and Fabricus! You also, O girl, may, when in your cups, read the naughtiness and sportive sallis of my little book, though you may be from Patavium. Lucretia blushed and laid down my volume; but Brutus was present. Brutus, go away: she will read it.

[tr. Ker (1919)]Grave reader, go -- wherever you may please --

I'm writing now for Roman cits at ease.

This scroll is full of Priapean rhymes

And sound of castanets from Spanish climes.

Though you more stern than ancient Curius be

You will be fired, methinks, if you read me.

Yet modest maidens at this sportive book

May in their cups perchance with favour look,

And matrons hide it from their lords away --

Meaning to finish it some other day.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "A Warning to Prudes"]Too serious reader, you may leave at this point and go where you please. I wrote these pieces for the city gown; now my page frolics with verse of Lampsacus and clashes the cymbals with Tartesian hand. Oh, how often you will strike your garment with rigid member, though you be graver than Curius and Fabricius. You also, my girl, will not be dry as you read the naughty jests of my little book, though you come from Patavium. Lucretia blushed and put my book aside, but that was in front of Brutus. Brutus, withdraw: she will read.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]You can leave now, Reader, over-severe,

go, where you please: I write for the city;

my page, now, runs wild with Priapic verse,

strikes the cymbals, with a dancing-girl’s hand.

O, how you’ll beat your cloak in rigid vein,

though you’re weightier than Curius, Fabricius!

You too, that read naughty jokes in my little book,

you’ll be wet, girl, though you’re from moral Padua.

Lucretia would have blushed, and shut my volume,

while Brutus was there; but when he left: she’d have read.

[tr. Kline (2006)]Persnickety readers, time to leave!

I now write stuff to make you grieve.

My toga off, my lines will jiggle

And with the bellydancer wriggle.

Now what we wear will ask no pardon

For standing out with sculptured hard-on.

To make the Founding Fathers horny,

And Boston matrons less than thorny --

They'll lather up between their thighs

And wonder at their fellows' size.

Of course Lucretia will not look

Till Brutus goes -- then: Seize the book!

[tr. Wills (2007)]Let every prudish reader use his feet

And bugger off -- I write for the elite.

My verses gambol with Priapic verve

As dancing harlots' patter starts a nerve.

Though stern as Curius or like Fabricius,

Your prick will stiffen and grow vicious.

Girls while they drink -- even the chastest folk --

Will read each naughty word and dirty joke.

Lucretia blushes, throws away my book.

Her husband goes. She takes another look.

[tr. Reid]

Quotations about:

readers

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

There are three difficulties in authorship: to write anything worth the publishing, to find honest men to publish it, and to get sensible men to read it.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon: or, Many Things in Few Words, Preface (1820)

(Source)

This is perhaps a not unimportant counsel to give to writers: write nothing that does not give you great pleasure; emotion passes easily from writer to reader.

[Ce ne serait peut-être pas un conseil peu important à donner aux écrivains, que celui-ci: n’écrivez jamais rien qui ne vous fasse un grand plaisir; l’émotion se propage aisément de l’écrivain au lecteur.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 23 “Des Qualités de l’Écrivain [On the Qualities of Writers],” ¶ 58 (1850 ed.) [tr. Lyttelton (1899), ch. 22, ¶ 25]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:This were perhaps not an unimportant advice to give to writers: never write any thing that does not give you great enjoyment; emotion is easily propagated from the writer to the reader.

[tr. Calvert (1866), ch. 15]And perhaps there is no advice to give a writer more important than this: -- Never write anything that does not give you great pleasure.

[tr. Auster (1983)], 1823 entry]