The solemn ritual continued. The pastor gave his final blessing. The coffin was lowered into the grave and earth cast on it; the most final sound in the world, Phryne thought, clods thudding hollowly on the lid.

Kerry Greenwood (b. 1954) Australian author and lawyer

Phryne Fisher No. 11, Away with the Fairies, ch. 18 (2001)

(Source)

When I am dead, I hope it may be said:

“His sins were scarlet, but his books were read.”Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) Franco-British writer, historian [Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc]

Poem (1923), “Epigram 1: On His Books,” Sonnets and Verse

(Source)

Sometimes called "An Author's Hope."

“What you do in this world is a matter of no consequence,” returned my companion, bitterly. “The question is, what can you make people believe that you have done?”

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) British writer and physician

Story (1886-04), “A Study in Scarlet,” Part 2, ch. 7 [Holmes], Beeton’s Christmas Annual, Vol. 28 (1887-11-21)

(Source)

Is not every true Reformer, by the nature of him, a Priest first of all? He appeals to Heaven’s invisible justice against Earth’s visible force; knows that it, the invisible, is strong and alone strong. He is a believer in the divine truth of things; a seer, seeing through the shows of things; a worshipper, in one way or the other, of the divine truth of things; a Priest, that is. If he be not first a Priest, he will never be good for much as a Reformer.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

Lecture (1840-05-15), “The Hero as Priest,” Home House, Portman Square, London

(Source)

The lecture notes were collected by Carlyle into On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, Lecture 4 (1841).

Much of man’s thinking is propaganda of his appetites.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 261 (1955)

(Source)

The man who wont beleave enny thing he kant see, aint so wize az a mule, for they will kick at a thing in the dark.

[The man who won’t believe anything he can’t see, ain’t so wise as a mule, for they will kick at a thing in the dark.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Josh Billings’ Farmer’s Allminax, 1871-06 (1871 ed.)

(Source)

For men ought not to be so elated by the dignity of the affairs which they have undertaken to manage, as to have no regard to their ease; nor ought they to dwell with fondness on any sort of ease which is inconsistent with dignity.

[Neque enim rerum gerendarum dignitate homines ecferri ita convenit ut otio non prospiciant, neque ullum amplexari otium quod abhorreat a dignitate.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Pro Sestio [For Publius Sestius], ch. 45 / sec. 98 (56-02 BC) [tr. Yonge (1891)]

(Source)

Part of Cicero's discussion of otium cum dignitate ("peace with dignity"), an idealized active private life after retiring from public service. See here for more.

(Source (Latin)). Other translations:For neither is it fitting that men be so carried away by political freedom as to make no provision for tranquility, nor to accept any tranquility which is inconsistent with freedom.

[tr. Hickie (1888)]For just as it ill befits men to be so carried away by the dignity of a public career that they are indifferent in peace, so too it is unfitting for them to welcome a peace which is inconsistent with dignity.

[tr. Gardner (Loeb) (1958)]

Wars bring scars.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1745 ed.)

(Source)

Our understanding is conducted solely by means of the word: anyone who falsifies it betrays public society. It is the only tool by which we communicate our wishes and our thoughts; it is our soul’s interpreter: if we lack that, we can no longer hold together; we can no longer know each other. When words deceive us, it breaks all intercourse and loosens the bonds of our polity.

[Nostre intelligence se conduisant par la seule voye de la parolle, celuy qui la faulse, trahit la societé publique. C’est le seul util, par le moyen duquel se communiquent noz volontez & noz pensees : c’est le truchement de nostre ame : s’il nous faut, nous ne nous tenons plus, nous ne nous entreconnoissons plus. S’il nous trompe, il rompt tout nostre commerce, & dissoult toutes les liaisons de nostre police.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 2, ch. 18 (2.18), “Of Giving the Lie [Du Démentir]” (1578–79) [tr. Screech (1987)]

(Source)

This essay (and this passage) appeared in the 1st (1580) edition.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Our intelligence being onely conducted by the way of the Worde: Who so falsifieth the same, betraieth publike society. It is the onely instrument, by meanes wherof our wils and thoughts are communicated: it is the interpretour of our souls: If that faile us we hold our selves no more, we enterknow one another no longer. If it deceive us, it breaketh all our commerce, and dissolveth all bonds of our policie.

[tr. Florio (1603)]Our intelligence being by no other canal to be conveyed to one another but by words, he, who falsifies them, betrays public society: it is the only tube through which we communicate our thoughts and wills to one another; it is the interpreter of the soul, and, if it fails us, we no longer know, nor have any farther tie upon another: if that deceive us, it breaks all our correspondence, and dissolves all the bands of our government.

[tr. Cotton (1686)]Our intelligence being by no other way communicable to one another but by a particular word, he who falsifies that betrays public society. ’Tis the only way by which we communicate our thoughts and wills; ’tis the interpreter of the soul, and if it deceive us, we no longer know nor have further tie upon one another; if that deceive us, it breaks all our correspondence, and dissolves all the ties of government.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]Our intelligence being conducted solely by the way of the word, he who falsifies that betrays all society. It is the only instrument by means of which our desires and our thoughts are exchanged; it is the interpreter of our souls; if it fails us, we no longer have any hold upon one another, we no longer mutually know one another. If it deceives us, it severs all our intercourse and dissolves all the ties of our government.

[tr. Ives (1925)]Our intercourse being carried on solely by means of the word, he who falsifies that is a traitor to society. It is the only instrument by which our thoughts and wills are communicated, it is the interpreter of our soul. If it fails us, we no longer hold together, we no longer know one anther. If it deceives us, it breaks up all our intercourse and dissolves all the ties of our government.

[tr. Zeitlin (1934)]Since mutual understanding is brought about solely by way of words, he who breaks his word betrays human society. It is the only instrument by means of which our wills and thoughts communicate, it is the interpreter of our soul. If it fails us, we have no more hold on each other, no more knowledge of each other. If it deceives us, it breaks up all our relations and dissolves all the bonds of our society.

[tr. Frame (1943)]

SARAH JANE: I mean, well, whatever’s in that Tower, it’s got enormous powers and, well, what can we do against it?

THE DOCTOR: What I’ve always done, Sarah Jane. Improvise.

Doctor Who (1963-1989) British science fiction television series (BBC)

20xS1 “The Five Doctors,” Part 2 (1983-11-23) [w. Terrance Dicks]

(Source)

(Source (Video); dialog confirmed). This 20th Anniversary special feature was originally broadcast as a feature-length TV movie. For later releases, it was broken into four parts/episodes.

We find what we are looking for. If we are looking for life and love and openness and growth, we are likely to find them. If we are looking for witchcraft and evil, we’ll likely find them, and we may get taken over by them.

Madeleine L'Engle (1918-2007) American writer

Speech (1983-11-16), “Dare To Be Creative,” Lecture, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

(Source)

“Oh, all right,” said the old man. “Here’s a prayer for you. Got a pencil?”

“Yes,” said Arthur.

“It goes like this. Let’s see now: ‘Protect me from knowing what I don’t need to know. Protect me from even knowing that there are things to know that I don’t know. Protect me from knowing that I decided not to know about the things that I decided not to know about. Amen.’ That’s it. It’s what you say silently inside yourself anyway, so you may as well have it out in the open.”

“Hmmmm,” said Arthur. “Well, thank you –”

“There’s another prayer that goes with it that’s very important,” continued the old man, “so you’d better jot this down, too.”

“Okay.”

“It goes, ‘Lord, lord, lord …’ It’s best to put that bit in, just in case. You can never be too sure. ‘Lord, lord, lord. Protect me from the consequences of the above prayer. Amen.’ And that’s it. Most of the trouble people get into in life comes form leaving out that last part.”Douglas Adams (1952-2001) English author, humorist, screenwriter

Hitchhiker’s Guide No. 5, Mostly Harmless, ch. 9 (1992)

(Source)

Ironically, most quotations of the above prayer leave out the "very important" second part.

The values communicated by status-insecure parents are such that their children learn to put personal success and the acquisition of power above all else. They are taught to judge people for their usefulness rather than their likableness. Their friends, and even future marriage partners, are selected and used in the service of personal advancement; love and affection take second place to knowing the right people. They are taught to eschew weaknesses and passivity, to respect authority, and to despise those who have not made the socio-economic grade. Success is equated with social esteem and material advantage, rather than with more spiritual values.

Norman F. Dixon (1922-2013) British cognitive psychologist, author, military engineer

On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, Part 2, ch. 22 “Authoritarianism” (1976)

(Source)

I have known some pacifists who wished history taught without reference to wars, and thought that children should be kept as long as possible ignorant of the cruelty in the world. But I cannot praise the “fugitive and cloistered virtue” that depends upon absence of knowledge. As soon as history is taught at all, it should be taught truthfully. If true history contradicts any moral we wish to teach, our moral must be wrong, and we had better abandon it. I quite admit that many people, including some of the most virtuous, find facts inconvenient, but that is due to a certain feebleness in their virtue. A truly robust morality can only be strengthened by the fullest knowledge of what really happens in the world.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

Education and the Good Life, Part 2, ch. 11 “Affection and Sympathy” (1926)

(Source)

The nation that complacently and fearfully allows its artists and writers to become suspected rather than respected is no longer regarded as a nation possessed with humor or depth.

James Thurber (1894-1961) American cartoonist and writer

Essay (1958-12-07), “State of the Nation’s Humor: ‘On the Brink of Was,'” New York Times Magazine

(Source)

The Gluttons dig their own graves with their teeth.

[Le gourmans, sont leurs fosses avec leurs dents.]

James Howell (c. 1594–1666) Welsh historian and writer

Paroimiographia [Παροιμιογραφία]: Proverbs, or, Old Sayed Sawes & Adages, “Proverbs in French” (1659) [compiler]

(Source)

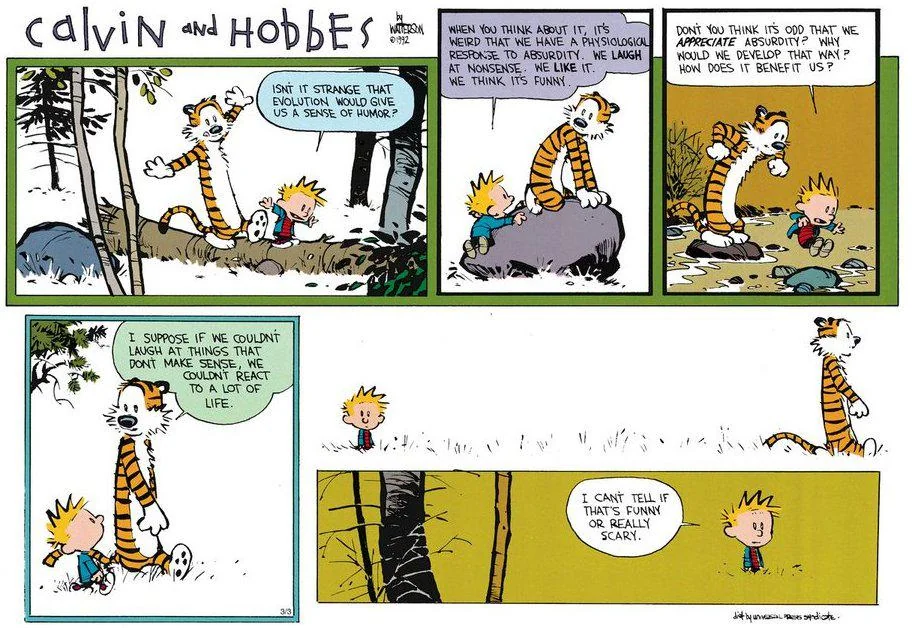

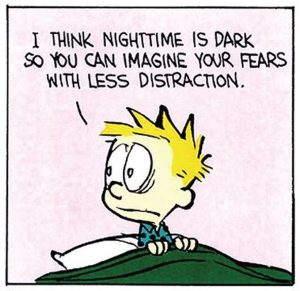

CALVIN: No one recognizes my hints to smother me with affection.

AUTHENTIC, adj. Indubitably true — in someone’s opinion.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) American writer and journalist

“Authentic,” “Devil’s Dictionary” column, San Francisco Wasp (1881-04-09)

(Source)

Not collected in later books.

Organizing is what you do before you do something, so that when you do it, it is not all mixed up.

A. A. Milne (1882-1956) English poet and playwright [Alan Alexander Milne]

(Attributed)

Widely quoted and attributed to Milne, but I can find no instance of it with an actual, proven citation.

Ross Webber in Management: Basic Elements of Managing Organizations (1979) gives the following:In A. A. Milne's childhood classic Winnie the Pooh, Christopher Robin tells his group of stuffed-animal friends that before they can search for the North Pole they ought to get organized. Pooh asks what getting organized means, and Christopher replies, "Organizing is what you do before you do something, so that when you do it, it is not all mixed up."

All well and good, and Christopher Robin does organize such an expedition ("expotition") to the North Pole in that book -- but never says anything of the sort. It is possible that the line derives from a Disney animated adaptation, but could not confirm this.

Samuel told the people who were asking him for a king everything that the Lord had said to him. “This is how your king will treat you,” Samuel explained.

“He will make soldiers of your sons; some of them will serve in his war chariots, others in his cavalry, and others will run before his chariots. He will make some of them officers in charge of a thousand men, and others in charge of fifty men. Your sons will have to plow his fields, harvest his crops, and make his weapons and the equipment for his chariots.

“Your daughters will have to make perfumes for him and work as his cooks and his bakers.

“He will take your best fields, vineyards, and olive groves, and give them to his officials. He will take a tenth of your grain and of your grapes for his court officers and other officials. He will take your servants and your best cattle and donkeys, and make them work for him. He will take a tenth of your flocks. And you yourselves will become his slaves.

“When that time comes, you will complain bitterly because of your king, whom you yourselves chose, but the Lord will not listen to your complaints.”

The people paid no attention to Samuel, but said, “No! We want a king.”The Bible (The Old Testament) (14th - 2nd C BC) Judeo-Christian sacred scripture [Tanakh, Hebrew Bible], incl. the Apocrypha (Deuterocanonicals)

Book 9: 1 Samuel 8:10ff (1 Sam. 8:10-19) [GNT (1992 ed.)]

(Source)

Alternate translations:And Samuel told all the words of the Lord unto the people that asked of him a king. And he said, This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you:

He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots. And he will appoint him captains over thousands, and captains over fifties; and will set them to ear his ground, and to reap his harvest, and to make his instruments of war, and instruments of his chariots.

And he will take your daughters to be confectionaries, and to be cooks, and to be bakers.

And he will take your fields, and your vineyards, and your oliveyards, even the best of them, and give them to his servants. And he will take the tenth of your seed, and of your vineyards, and give to his officers, and to his servants. And he will take your menservants, and your maidservants, and your goodliest young men, and your asses, and put them to his work. He will take the tenth of your sheep: and ye shall be his servants.

And ye shall cry out in that day because of your king which ye shall have chosen you; and the Lord will not hear you in that day.

Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel; and they said, Nay; but we will have a king over us.

[KJV (1611)]All that Yahweh had said Samuel repeated to the people who were asking him for a king. He said, "These will be the rights of the king who is to reign over you.

"He will take your sons and assign them to his chariotry and cavalry, and they will run in front of his chariot. He will use them as leaders of a thousand and leaders of fifty; he will make them plough his ploughland and harvest his harvest and make his weapons of war and the gear for his chariots.

"He will also take your daughters as perfumers, cooks and bakers.

"He will take the best of your fields, of your vineyards and olive groves and give them to his officials. He will tithe your crops and vineyards to provide for his eunuchs and his officials. He will take the best of your manservants and maidservants, of your cattle and your donkeys, and make them work for him. He will tithe your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves.

"When that day comes, you will cry out on account of the king you have chosen for yourselves, but on that day God will not answer you."

The people refused to listen to the words of Samuel. They said, 'No! We want a king."

[JB (1966)]Everything that Yahweh had said, Samuel then repeated to the people who were asking him for a king. He said, "This is what the king who is to reign over you will do.

"He will take your sons and direct them to his chariotry and cavalry, and they will run in front of his chariot. He will use them as leaders of a thousand and leaders of fifty; he will make them plough his fields and gather in his harvest and make his weapons of war and the gear for his chariots.

"He will take your daughters as perfumers, cooks and bakers.

"He will take the best of your fields, your vineyards and your olive groves and give them to his officials. He will tithe your crops and vineyards to provide for his courtiers and his officials. He will take the best of your servants, men and women, of your oxen and your donkeys, and make them work for him. He will tithe your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves.

"When that day comes, you will cry aloud because of the king you have chosen for yourselves, but on that day Yahweh will not hear you."

The people, however, refused to listen to Samuel. They said, "No! We are determined to have a king."

[NJB (1985)]Then Samuel explained everything the Lord had said to the people who were asking for a king. “This is how the king will rule over you,” Samuel said:

“He will take your sons, and will use them for his chariots and his cavalry and as runners for his chariot. He will use them as his commanders of troops of one thousand and troops of fifty, or to do his plowing and his harvesting, or to make his weapons or parts for his chariots.

"He will take your daughters to be perfumers, cooks, or bakers.

"He will take your best fields, vineyards, and olive groves and give them to his servants. He will give one-tenth of your grain and your vineyards to his officials and servants. He will take your male and female servants, along with the best of your cattle and donkeys, and make them do his work. He will take one-tenth of your flocks, and then you yourselves will become his slaves!

"When that day comes, you will cry out because of the king you chose for yourselves, but on that day the Lord won’t answer you.”

But the people refused to listen to Samuel and said, “No! There must be a king over us."

[CEB (2011)]So Samuel reported all the words of the Lord to the people who were asking him for a king. He said, “These will be the ways of the king who will reign over you:

"He will take your sons and appoint them to his chariots and to be his horsemen, and to run before his chariots, and he will appoint for himself commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties and some to plow his ground and to reap his harvest and to make his implements of war and the equipment of his chariots.

"He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers.

"He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive orchards and give them to his courtiers. He will take one-tenth of your grain and of your vineyards and give it to his officers and his courtiers. He will take your male and female slaves and the best of your cattle and donkeys and put them to his work. He will take one-tenth of your flocks, and you shall be his slaves.

"And on that day you will cry out because of your king, whom you have chosen for yourselves, but the Lord will not answer you on that day.”

But the people refused to listen to the voice of Samuel; they said, “No! We are determined to have a king over us."

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]Samuel reported all God’s words to the people, who were asking him for a king. He said, “This will be the practice of the king who will rule over you:

"He will take your sons and appoint them as his charioteers and riders, and they will serve as outrunners for his chariots. He will appoint them as his chiefs of thousands and of fifties; or they will have to plow his fields, reap his harvest, and make his weapons and the equipment for his chariots.

"He will take your daughters as perfumers, cooks, and bakers.

"He will seize your choice fields, vineyards, and olive groves, and give them to his courtiers. He will take a tenth part of your grain and vintage and give it to his eunuchs and courtiers. He will take your male and female slaves, your choice young men, and your donkeys, and put them to work for him. He will take a tenth part of your flocks, and you shall become his slaves.

"The day will come when you cry out because of the king whom you yourselves have chosen; and God will not answer you on that day.”

But the people would not listen to Samuel’s warning. “No,” they said. “We must have a king over us."

[RJPS (2023 ed.)]

There need not be much integrity for a monarchical or despotic government to maintain or sustain itself. The force of the laws in the one, and the prince’s ever-raised arm in the other, can rule or contain the whole. But in a popular state there must be an additional spring, which is virtue.

[Il ne faut pas beaucoup de probité, pour qu’un gouvernement monarchique, ou un gouvernement despotique, se maintiennent ou se soutiennent. La force des loix dans l’un, le bras du prince toujours levé dans l’autre, reglent ou contiennent tout. Mais, dans un état populaire, il faut un ressort de plus, qui est la VERTU.]

Charles-Lewis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) French political philosopher

Spirit of Laws [The Spirit of the Laws; De l’esprit des lois], Book 3, ch. 3 (3.3) (1748) [tr. Cohler/Miller/Stone (1989)]

(Source)

In his Preface, Montesquieu clarifies:For the understanding of the first four books of this work, it must be noted that what I call virtue in the republic is love of the homeland, in other words love of equality. It is not a moral virtue, nor a Christian virtue, it is political virtue; and this virtue is what drives republican government, as honor is what drives monarchy. I have therefore called political virtue love of the homeland and of equality.

(Source (French)). Other translations:There is no great share of probity necessary to support a monarchical or despotic government: the force of laws, in one, and the prince’s arm, in the other, are sufficient to direct and maintain the whole. But, in a popular state, one spring more is necessary, namely, virtue.

[tr. Nugent (1750)]It does not take much probity for a monarchical or despotic government to maintain or sustain itself. The force of the laws in the first, and the ever-threatening arm of the prince in the second, determine or contain everything. But a popular state needs to be driven by something more, which is VIRTUE.

[tr. Stewart (2018)]

A preoccupation with the so-called bottom line of profit and loss statements, coupled with a lust for expansion, is creating an environment in which fewer businessmen honor traditional values; where responsibility is increasingly disassociated from the exercise of power; where skill in financial manipulation is valued more than actual knowledge and experience in the business; where attention and effort is directed mostly to short-term considerations, regardless of longer range consequences.

Hyman Rickover (1900-1986) American naval engineer, submariner, US Navy Admiral

Speech (1982-01-28), Joint Economic Committee, U.S. Congress, 97th Congress, 2nd Session

(Source)

Look, examine, reflect. You hold capital punishment up as an example. Why? Because of what it teaches. And just what is it that you wish to teach by means of this example? That thou shalt not kill. And how do you teach that “thou shalt not kill”? By killing.

[Voyez, examinez, réfléchissez. Vous tenez à l’exemple [de la peine de mort]. Pourquoi? Pour ce qu’il enseigne. Que voulez-vous enseigner avec votre exemple? Qu’il ne faut pas tuer. Et comment enseignez-vous qu’il ne faut pas tuer? En tuant.]

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) French writer

Speech (1848-09-15), “Plaidoyer contre la peine de mort [An argument against the death penalty],” Assemblée Constituante, Paris

(Source)

(Source (French)).

I have been unable to find the origin of the English translation that is widely used for this quotation (let alone an English record of the entire speech).

I do have a compulsion to read in out-of-the-way places, and it is often a blessing; on the other hand, it sometimes comes between me and what I tell the children is “my work.” As a matter of fact, I will read anything rather than work. And I don’t mean interesting things like the yellow section of the telephone book or the enclosures that come with the Bloomingdale bill about McKettrick classics in sizes 12 to 20, blue, brown, or navy @ 12.95 (by the way, did you know that colored facial tissue is now on sale at the unbelievably low price of 7.85 a carton? ). The truth is that, rather than put a word on paper, I will spend a whole half hour reading the label on a milk-of-magnesia bottle. “Philips’ Milk of Magnesia,” I read with the absolute absorption of someone just stumbling on Congreve, “is prepared only by the Charles H. Philips Co., division of Sterling Drug, Inc. Not to be used when abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or other symptoms of appendicitis are present, etc.”

Jean Kerr (1922-2003) American author and playwright [b. Bridget Jean Collins]

Essay (1957), “Introduction,” Please Don’t Eat the Daisies

(Source)

People who live at the lower ends of watersheds cannot be isolationists — or not for long. Pretty soon they will notice that water flows, and that will set them to thinking about the people upstream who either do or do not send down their silt and pollutants and garbage. Thinking about the people upstream out to cause further thinking about the people downstream. Such pondering on the facts of gravity and the fluidity of water shows us that the golden rule speaks to a condition of absolute interdependency and obligation. People who live on rivers — or, in fact, anywhere in a watershed — might rephrase the rule in this way: Do unto those downstream as you would have those upstream do unto you.

Wendell Berry (b. 1934) American farmer, educator, poet, conservationist

Essay (1997), “Watershed and Commonwealth,” Citizenship Papers (2003)

(Source)

See Matthew 7:12.

LUCIUS: From hence, let fierce contending nations know,

What dire effects from civil discord flow.Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Cato, Act 5, sc. 4, l. 106ff (1713)

(Source)

After Cato's suicide during the civil war against Julius Caesar.

MEMBRILLO: All day long, Manny, I sort through pure sadness. I find evidence, and I piece together stories. But none of my stories end well — they all end here. And the moral of every story is the same: we may have years, we may have hours, but sooner or later, we push up flowers.

Tim Schafer (b. 1967) American video game designer.

Grim Fandango, “Year 2,” computer game (1998)

(Source)

(Source (Video); dialog confirmed). To Manny, in the morgue.

MALCOLM: Be comforted.

Let’s make us med’cines of our great revenge,

To cure this deadly grief.MACDUFF: He has no children. All my pretty ones?

Did you say “all”? O hell-kite! All?

What, all my pretty chickens and their dam

At one fell swoop?MALCOLM: Dispute it like a man.

MACDUFF: I shall do so,

But I must also feel it as a man.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Macbeth, Act 4, sc. 3, l. 252ff (4.3.252-261) (1606)

(Source)

Macduff, learning his family and household have been killed on Macbeth's orders.

In the jungles of central Klatch there are, indeed, lost kingdoms of mysterious Amazonian princesses who capture male explorers for specifically masculine duties. These are indeed rigorous and exhausting and the luckless victims do not last long.*

* This is because wiring plugs, putting up shelves, sorting out the funny noises in attics, and mowing lawns can eventually reduce even the strongest constitution.

And yet I am held responsible for my belief. Then why does not God give me the evidence? They say he has. In what? In an inspired book. But I do not understand it as they do. Must I be false to my understanding? They say: “When you come to die you will be sorry if you do not.” Will I be sorry when I come to die that I did not live a hypocrite? Will I be sorry that I did not say I was a Christian when I was not? Will the fact that I was honest put a thorn in the pillow of death? Cannot God forgive me for being honest? They say that when he was in Jerusalem he forgave his murderers, but now he will not forgive an honest man for differing from him on the subject of the Trinity.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, freethinker, orator

Lecture (1884-01-20), “Orthodoxy,” Tabor Opera House, Denver, Colorado

(Source)

Published as its own book in 1884.

Fortune nor home not more the man can cheer,

Who lives a prey to covetise or fear,

Than may a picture’s richest hues delight

Eyes that with dropping rheum are thick of sight,

Or warm soft lotions soothe a gout-racked foot,

Or aching ears be charmed by twangling lute.

On minds unquiet joy has lost its power;

In a foul vessel everything turns sour.[Qui cupit aut metuit, iuvat ilium sic domus et res,

Ut lippum pictae tabulae, fomenta podagrum,

Auriculas citbarae collecta sorde dolentes.

Sincerumst nisi vas, quodcumque infundis acescit

Sperne voluptate.]Horace (65–8 BC) Roman poet, satirist, soldier, politician [Quintus Horatius Flaccus]

Epistles [Epistularum, Letters], Book 1, ep. 2 “To Lollius,” l. 51ff (1.2.51-54) (14 BC) [tr. Martin (1881)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Other translations:The wisshinge, and the tremblinge chuffe his house and good doth please,

As portraytures the poreblind eyes, as bathes, the gowtie ease.

As musicke dothe delite the eares with matter stuffde, and sore.

The vessels sowers what so it takes if it be fowle before.

[tr. Drant (1567)]Who fears, or covets: House to him and Ground,

Are Pictures to blind men, Incentives bound

About a gouty Limb, Musick t'an ear

Dam'd up with filth. A vessel not sincere

Sowres whatsoe're you put into't.

[tr. Fanshawe; ed. Brome (1666)]He that desires or fears, diseas'd in mind,

Wealth profits him as Pictures do the blind;

Plaisters the Gouty Feet; and charming Airs

And sweetest sounds the stuft and troubled Ears:

The musty Vessels sour what they contain.

[tr. Creech (1684)]Houses and riches gratify the breast

For lucre lusting, or with fear deprest,

As pictures, glowing with a vivid light,

With painful pleasure charm a blemisht sight;

As chafing soothes the gout, or music cheers

The tingling organs of imposthum'd ears.

Your wine grows acid when the cask is foul.

[tr. Francis (1747)]Who frets or covets, wealth can please no more

Than pictures him whose eyes with rheum run o'er --

Than furst an flannels can the cripple cheer,

Or warbling music charm an aching ear.

Life's every relish lies beyond his power,

As in the tainted vessel all turns sour.

[tr. Howes (1845)]To him that is a slave to desire or to fear, house and estate do just as much good as paintings to a sore-eyed person, fomentations to the gout, music to ears afflicted with collected matter. Unless the vessel be sweet, whatever you pour into it turns sour.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]Who fears or hankers, land and country-seat

Soothe just as much as tickling gouty feet,

As pictures charm an eye inflamed and blear,

As music gratifies an ulcered ear.

Unless the vessel whence we drink is pure,

Whate'er is poured therein turns foul, be sure.

[tr. Conington (1874)]A house and wealth afford like pleasure to him who is covetous or fearful, as paintings do to a person with defective sightk, fomentations to a gouty man, or music to those whose ears suffer from accumulated dirt. Except a jar be clean, whatever you may pour in turns sour.

[tr. Elgood (1893)]If a mind is bound by greed or harassed by fears, his house, his home and all his possessions will give him no more pleasure than paintings do to the blind, warm blankets the feverish or music the deaf. In an unclean pitcher sweet milk soon turns sour.

[tr. Dana/Dana (1911)]To one with fears or cravings, house and fortune give as much pleasure as painted panels to sore eyes, warm wraps to the gout, or citherns to ears that suffer from secreted matter. Unless the vessel is clean, whatever you pour in turns sour.

[tr. Fairclough (Loeb) (1926)]His house and estate are as much of a pleasure to him

Who wants something more (or is deathly afraid he won't get it)

As dazzling canvases are to a man with sore eyes,

Or nice wram robes to a man who suffers from gout,

Or the music of mournful guitars to infected ears.

If the vase isn't clean, whatever you put in turns sour.

[tr. Palmer Bovie (1959)]A man who desires or fears enjoys his good as much

as a sore-eyed man likes art, a man with gout

fine shoes, someone with wax-plugged hears a cithara.

Anything you pour into a dirty pot gets spoiled.

[tr. Fuchs (1977)]A miser, or a man endlessly

Greedy, enjoys his mansion, his rolling meadows, as much

As a sore-eyed man takes pleasure in paintings, a gouty man relishes

Hot cloths, a man with pus-filled ears loves music.

If the cup isn't clean, everything you drink is dirty.

[tr. Raffel (1983)]If your life is governed

By cravings for what you lack, or else by fear

Of losing what you have, then what you have,

Your house and your possessions, give you as much

Pleasure as a picture gives a blind man,

Or an elegant pair of shoes gives a man with gout,

Or music gives to an ear stuffed up with wax.

A glass that isn't clean will guarantee

That whatever you pour into it will sour.

[tr. Ferry (2001)]A man with fear or desire has as much pleasure from his house

and possessions as sore eyes from a picture, gouty feet

from muffs, or ears from a lyre when aching with lumps of dirt.

When a jar is unclean, whatever you fill it with soon goes sour.

[tr. Rudd (2005 ed.)]House and fortune grant

As much pleasure to one who’s full of fear and craving

As painting to sore eyes, poultice to gouty joint,

Or lute to ears that ache from accumulated wax.

Unless the jar is clean whatever you pour in sours.

[tr. Kline (2015)]

If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.

George Orwell (1903-1950) English journalist, essayist, writer [pseud. of Eric Arthur Blair]

Essay (1946-04), “Politics and the English Language,” Horizon Magazine

(Source)

Well, I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the world. I’m a consulting detective, if you can understand what that is. Here in London we have lots of government detectives and lots of private ones. When these fellows are at fault, they come to me, and I manage to put them on the right scent. They lay all the evidence before me, and I am generally able, by the help of my knowledge of the history of crime, to set them straight. There is a strong family resemblance about misdeeds, and if you have all the details of a thousand at your finger ends, it is odd if you can’t unravel the thousand and first.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) British writer and physician

Story (1886-04), “A Study in Scarlet,” Part 1, ch. 2 [Holmes], Beeton’s Christmas Annual, Vol. 28 (1887-11-21)

(Source)

But his [Shakespeare’s] laughter seems to pour from him in floods; he heaps all manner of ridiculous nicknames on the butt he is bantering, tumbles and tosses him in all sorts of horse-play; you would say, with his whole heart laughs. And then, if not always the finest, it is always a genial laughter. Not at mere weakness, at misery or poverty; never. No man who can laugh, what we call laughing, will laugh at these things. It is some poor character only desiring to laugh, and have the credit of wit, that does so. Laughter means sympathy; good laughter is not “the crackling of thorns under the pot.” Even at stupidity and pretension this Shakspeare does not laugh otherwise than genially. Dogberry and Verges tickle our very hearts; and we dismiss them covered with explosions of laughter: but we like the poor fellows only the better for our laughing; and hope they will get on well there, and continue Presidents of the City-watch. Such laughter, like sunshine on the deep sea, is very beautiful to me.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

Lecture (1840-05-12), “The Hero as Poet,” Home House, Portman Square, London

(Source)

The spelling of Shakespeare's name is as used by Carlyle (and is one of the variants Shakespeare actually used).

The lecture notes were collected by Carlyle into On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, Lecture 3 (1841).

Whenever a minister haz preached a sermon that pleazes the whole congregashun, he probably haz preached one that the Lord wont endorse.

[Whenever a minister has preached a sermon that pleases the whole congregation, he probably haz preached one that the Lord won’t endorse.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Josh Billings’ Farmer’s Allminax, 1871-06 (1871 ed.)

(Source)

Lying is a villainous vice, and an ancient writer depicts it as most shameful when he says that to lie is to manifest contempt of God together with fear of man. It is not possible to represent more fully the horror, the vileness, the outrageousness of it. For what can be conceived more villainous than to be cowardly with respect to men, and audacious with respect to God?

[C’est un vilain vice, que le mentir; & qu’un ancien peint bien honteusement, quand il dit, que c’est donner tesmoignage de mespriser Dieu, & quand & quand de craindre les hommes. Il n’est pas possible d’en representer plus richement l’horreur, la vilité & le desreiglement: Car que peut on imaginer plus vilain, que d’estre couart à l’endroit des hommes, & brave à l’endroit de Dieu?]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 2, ch. 18 (2.18), “Of Giving the Lie [Du Démentir]” (1578–79) [tr. Ives (1925)]

(Source)

This essay (and passage) appeared in the 1st (1580) edition, and was expanded in each succeeding edition.

The ancient writer mentioned is Plutarch in his Life of Lysander.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:To ly is a horrible-filthy vice; and which an auncient writer setteth forth very shamefully, when he saith, that whosoever lieth, witnesseth that he contemneth God and therewithal feareth men. It is impossible more richly to represent the horrour, the vilenesse and the disorder of it: For, What can be imagined so vile, and base, as to be a coward towardes men, and a boaster towardes God?

[tr. Florio (1603)]Lying is a base vice; a vice that one of the ancients paints in the most odious colours when he says, "That it is too manifest a contempt of God, and a fear of man." It is not possible more copiously to represent the horror, baseness, and irregularity of it; for what can be imagined more vile, than a man, who is a coward towards man, so courageous as to defy his Maker?

[tr. Cotton (1686)]Lying is a base vice; a vice that one of the ancients portrays in the most odious colors when he says, “that it is to manifest a contempt of God, and withal a fear of men.” It is not possible more fully to represent the horror, baseness, and irregularity of it; for what can a man imagine more hateful and contemptible than to be a coward toward men, and valiant against his Maker?

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]Lying is a base vice, and painted in its most shameful colours by one of the ancients, who says that to lie is to give proof that you despise god and at the same time are afraid of men. It is impossible to state its horror, its vileness, and its outrageousness more felicitously. For what baser thing can we imagine than to be a coward toward men and act the brave fellow toward God?

[tr. Zeitlin (1934)]Lying is an ugly vice, which an ancient paints in most shameful colors when he says that it is giving evidence of contempt for God, and at the same time of fear of men. It is not possible to represent more vividly the horror, the vileness, and the profligacy of it. For what can you imagine uglier than being a coward toward men and bold toward God?

[tr. Frame (1943)]Lying is a villein's vice, a vice which an Ancient paints full shamefully when he says that it gives testimony to contempt for God together with fear of men. It is not possible to show more richly the horror of it, its vileness and its disorderliness. For what can one imagine more serf-like than to be cowardly before men and defiant towards God?

[tr. Screech (1987)]

Many years ago, when A Wrinkle in Time was being rejected by publisher after publisher, I wrote in my journal, “I will rewrite for months or even years for an editor who sees what I am trying to do in this book and wants to make it better and stronger. But I will not, I cannot diminish and mutilate it for an editor who does not understand it and wants to weaken it.”

Now, the editors who did not understand the book and wanted the problem of evil soft peddled had every right to refuse to publish the book, as I had, sadly, the right and obligation to try to be true to it. If they refused it out of honest conviction, that was honorable. If they refused it for fear of trampling on someone else’s toes, that was, alas, the way of the world.Madeleine L'Engle (1918-2007) American writer

Speech (1983-11-16), “Dare To Be Creative,” Lecture, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

(Source)

Grown men, he told himself, in flat contradiction of centuries of accumulated evidence about the way grown men behave, do not behave like this.

Douglas Adams (1952-2001) English author, humorist, screenwriter

Hitchhiker’s Guide No. 4, So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish, ch. 11 [Arthur] (1984)

(Source)

It’s frightening to think that you mark your children merely by being yourself.

[C’est effrayant de penser qu’on marque ses enfants rien que par ce qu’on est.]

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) French author, existentialist philosopher, feminist theorist

Les Belles Images, ch. 3 (1966) [tr. O’Brian (1968)]

(Source)

CHORUS: Visitations of love that come

Raging and violent on a man

Bring him neither good repute nor goodness.

But if Aphrodite descends in gentleness

No other goddess brings such delight.[ΚΥΚΛΩΨ: ἔρωτες ὑπὲρ μὲν ἄγαν ἐλθόντες οὐκ εὐδοξίαν

οὐδ᾽ ἀρετὰν παρέδωκαν ἀνδράσιν: εἰ δ᾽ ἅλις ἔλθοι

Κύπρις, οὐκ ἄλλα θεὸς εὔχαρις οὕτως.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Medea [Μήδεια], l. 627ff, Second Stasimon, Strophe 1 (431 BC) [tr. Vellacott (1963)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Other translations:Th' immoderate Loves in their career,

Nor glory nor esteem attends,

But when the Cyprian Queen descends

Benignant from her starry sphere.

No Goddess can more justly claim

From man the grateful prayer.

[tr. Wodhull (1782)]When fierce conflicting passions urge

The breast where love is wont to glow,

What mind can stem the stormy surge

Which rolls the tide of human woe?

The hope of praise, the dread of shame,

Can rouse the tortur’d breast no more;

The wild desire, the guilty flame,

Absorbs each wish it felt before.

But if Affection gently thrills

The soul, by purer dreams possest,

The pleasing balm of mortal ills

In love can sooth the aching breast:

If thus thou comest in disguise,

Fair Venus! from thy native heaven,

What heart, unfeeling, would despise

The sweetest boon the Gods have given?

[tr. Byron (1807)]When with a wild impetuous sway

The Loves come rushing on the breast,

Each virtuous thought is rent away,

Each breath of fame supprest.

But when, confess'd her gentle reign,

Enchanting Venus deigns t'appear,

Of all the pow'rs of heav'n most dear,

She leads the Graces in her train.

[tr. Potter (1814)]The wild loves that force eager way

Nor worth nor fame on man confer,

But if come Cypris with meet sway

There is no gracious god like her.

[tr. Webster (1868)]When in excess and past all limits Love doth come, he brings not glory or repute to man; but if the Cyprian queen in moderate might approach, no goddess is so full of charm as she.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]The loves, when they come too impetuously, have given neither good report nor virtue among men, but if Venus come with moderation, no other Goddess is so benign.

[tr. Buckley (1892)]Love bringeth nor glory nor honour to men when it cometh restraining

Not its unscanted excess: but if Kypris, in measure raining

Her joy, cometh down, there is none other Goddess so winsome as she.

[tr. Way (Loeb) (1894)]Alas, the Love that falleth like a flood,

Strong-winged and transitory:

Why praise ye him? What beareth he of good

To man, or glory?

Yet Love there is that moves in gentleness,

Heart-filling, sweetest of all powers that bless.

[tr. Murray (1906)]When love is in excess

It brings a man no honor

Nor any worthiness.

But if in moderation Cypris comes,

There is no other power at all so gracious.

[tr. Warner (1944)]When the Loves descend in full force they never enhance

Men’s fame or virtue, but if Aphrodite approaches

With reserve, there is no more gracious goddess.

[tr. Podlecki (1989)]Loves that come to us in excess bring no good name or goodness to men. If Aphrodite comes in moderation, no other goddess brings such happiness.

[tr. Kovacs (Loeb) (1994)]When passions come upon men in strength beyond due measure, their gift is neither one of glory nor of greatness. But if the Cyprian tempers her visit, no other goddess is so gracious.

[tr. Davie (1996)]When Aphrodite arrives in the hearts of people, with no fuss and with no exaggerated madness, she is a very enjoyable visitor but, alas, overwhelming lust brings neither honour nor glory to any one.

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]Love coming on too strong

does not give glory or virtue

to men. But if Kypris comes in moderation,

no other goddess is so gracious.

[tr. Luschnig (2007)]Erotic love with too much passion

brings with it no fine reputation,

and nothing virtuous to men.

But if Aphrodite comes in smaller doses,

no other god is so desirable.

[tr. Johnston (2008)]Excess of passion brings no glory or honour to men.

[ed. Yeroulanos (2016)]Love that comes in great excess does not grant reputation or excellence; but if Aphrodite comes more gently, there is no other god who gives such great pleasure.

[tr. Ewans (2022)]When loves come excessive and past all limit, they bring neither good repute nor high ideals [aretē] to men; but if Aphrodite approaches in moderate strength, no goddess is so full of charm as she.

[tr. Coleridge / Ceragioli / Nagy / Hour25]

Truly, I live in dark times!

The guileless word is folly. A smooth forehead

Suggests insensitivity. The man who laughs

Has simply not yet had

The terrible news.

–

What kind of times are they, when

A talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

That man there calmly crossing the street

Is already perhaps beyond the reach of his friends

Who are in need?[Wirklich, ich lebe in finsteren Zeiten!

Das arglose Wort ist töricht. Eine glatte Stirn

Deutet auf Unempfindlichkeit hin. Der Lachende

Hat die furchtbare Nachricht

Nur noch nicht empfangen.

–

Was sind das für Zeiten, wo

Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist

Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele Untaten einschließt!

Der dort ruhig über die Straße geht

Ist wohl nicht mehr erreichbar für seine Freunde

Die in Not sind?]Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) German poet, playwright, director, dramaturgist

Poem (1938 ca.), “To Those Born Later [An die Nachgeborenen],” sec. 1, Svendborger Gedichte (1939) [tr. Willet / Manheim / Fried (1976)]

(Source)

Also translated as "To Those Who Follow in Our Wake" and "To Later Generations." Written while Brecht had left Germany for Denmark ("crossing the street").

An audio recording of the poem by Brecht.

(Source (German)). Other translations:Truly, I live in dark times

The innocent word is suspect.

An unwrinkled forehead

suggests insensitivity.

He who laughs

simply has not heard

the terrible news.

-

What times are these when

a conversation about trees

is almost a crime

because it includes

so much silence

about so many outrages!

[tr. Lettau (1978)]Truly, I live in dark times!

An artless word is foolish. A smooth forehead

Points to insensitivity. He who laughs

Has not yet received

The terrible news.

-

What times are these, in which

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

For in doing so we maintain our silence about so much wrongdoing!

And he who walks quietly across the street,

Passes out of the reach of his friends

Who are in danger?

[tr. Horton (2008)]Really, I live in dark times!

Innocent words are foolish. A smooth brow

Betrays insensitivity. Anyone left laughing

Simply has not yet heard

The terrible news.

-

What are these for times, where

A discussion about trees is almost a crime

Because it involves a silence about so many misdeeds!

He there peacefully crossing the street

Is probably no longer reachable for his friends

Who are in need?

[tr. Rienas (2009)]Really, I live in dark times!

Innocent words are foolish. An unfurrowed brow

Indicates apathy. He who laughs

Just hasn’t yet received

The terrible news.

-

What times are these, in which

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many misdeeds!

He who quietly crosses the street

Is probably no longer within reach of his friends

Who are in need?

[tr. Renaud (2016)]Truly, I live in dark times!

Innocent words are foolish. A smooth forehead

shows insensitivity. The guy laughing

has just not received

the terrible news yet.

-

What kind of times are these, where

talking about trees is almost a crime

when it means silence about so many atrocities!

That man calmly crossing the street

is probably no longer reachable by his friends

who need help.

As long as we are not actually destroyed, we can work to gain greater understanding of other peoples and to try to present to the peoples of the world the values of our own beliefs. We can do this by demonstrating our conviction that human life is worth preserving and that we are willing to help others to enjoy benefits of our civilization just as we have enjoyed it. (20 December 1961)

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962) First Lady of the US (1933–1945), politician, diplomat, activist

Column (1951-12-20), “My Day”

(Source)

Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ.

[Ἀλλήλων τὰ βάρη βαστάζετε καὶ οὕτως ἀναπληρώσετε τὸν νόμον τοῦ Χριστοῦ.]

The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Galatians 6: 2 [KJV (1611)]

(Source)

See Thomas à Kempis (c. 1420).

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:You should carry each other's troubles and fulfil the law of Christ.

[JB (1966)]Carry each other's burdens; that is how to keep the law of Christ.

[NJB (1985)]Help carry one another's burdens, and in this way you will obey the law of Christ.

[GNT (1992 ed.)]Carry each other’s burdens and so you will fulfill the law of Christ.

[CEB (2011)]Bear one another’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

Some men improve the world only by leaving it.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) Irish poet, wit, dramatist

(Spurious)

Not found in Wilde's writing; its earliest appearance is around AD 2000. Nor is a related quotation authentic to Wilde: "Some cause happiness wherever they go; other whenever they go," which first shows up in 1908, after Wilde's death.

Note that the orator Robert Ingersoll, discussing suppression of thought and mob mentality, wrote in his lecture "Plea for Individuality and Arraignment of the Church" (1873-12-21) (emphasis mine):It is mortifying to feel that you belong to a mental mob and cry "crucify him," because others do; that you reap what the great and brave have sown, and that you can benefit the world only by leaving it.

That is the earliest reference I can find to that phrasing, but it is unclear if the phrase was borrowed from Ingersoll and put into the mouth of Wilde.

And as for the argument that criticism [of government foreign policy] may give aid and comfort to some enemy, that is a form of blackmail unworthy of those who profess it. If it is to be accepted, we will have an end to genuine discussion of foreign policies, for it will inevitably be invoked to stop debate and criticism whenever that debate gets acrimonious or the criticism cuts too close to the bone. And to the fevered mind of the FBI, the CIA, and some Senators, criticism always gives aid and comfort to the enemy or cuts too close to

the bone.Henry Steele Commager (1902-1998) American historian, writer, activist

Essay (1965-12-18), “The Problem of Dissent,” Saturday Review

(Source)

Reprinted in Freedom and Order, Part 6 (1966).

Sections of the essay (including this portion) were read into the Congressional Record, Senate Proceedings (1969-06-26), as part of a speech by former Senator Wayne Morse (D-Oregon) at the commencement of Fairleigh Dickinson University (1969-06-07); Morse's speech was read in by Senator Gary Hart (D-Colo.).

When the savages of Louisiana want some fruit, they cut down the tree at the base and gather the fruit. That is how a despotic government works.

[Quand les sauvages de la Louisiane veulent avoir du fruit, ils coupent l’arbre au pied, & cueillent le fruit. Voilà le gouvernement despotique.]

Charles-Lewis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) French political philosopher

Spirit of Laws [The Spirit of the Laws; De l’esprit des lois], Book 5, ch. 13 (5.13) (1748) [tr. Stewart (2018)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Other translations:When the savages of Louisiana are desirous of fruit, they cut the tree to the root, and gather the fruit. This is an emblem of despotic government.

[tr. Nugent (1750)]When the savages of Louisiana want fruit, they cut down the tree and gather the fruit. There you have despotic government.

[tr. Cohler/Miller/Stone (1989)]

Another principle for successful application of a sophisticated technology is to resist the human inclination to hope that things will work out, despite evidence or suspicions to the contrary. This may seem obvious, but it is a human factor you must be conscious of and actively guard against. It can affect you in subtle ways, particularly when you have spent a lot of time and energy on a project and feel personally responsible for it, and thus somewhat possessive. It is a common human problem and it is not easy to admit what you thought was correct did not turn out that way.

Hyman Rickover (1900-1986) American naval engineer, submariner, US Navy Admiral

Essay (1979-05-24), Statement before the Subcommittee on Energy Research and Production, Committee on Science and Technology, US House of Representatives

(Source)

When dictatorship is a fact, revolution becomes a right.

[Quand la dictature est un fait, la révolution devient un droit.]

Victor Hugo (1802-1885) French writer

(Attributed)

While in keeping with his opposition to the regime of Napoleon III, I have been unable to find any primary source or citation in English or French for this quotation (that Time Magazine (1957-06-03) used the quote doesn't really count).

You can’t sleep until noon with the proper élan unless you have some legitimate reason for staying up until three (parties don’t count).

Jean Kerr (1922-2003) American author and playwright [b. Bridget Jean Collins]

Essay (1957), “Introduction,” Please Don’t Eat the Daisies

(Source)

The folly at the root of this foolish economy began with the idea that a corporation should be regarded, legally, as “a person.” But the limitless destructiveness of this economy comes about precisely because a corporation is not a person. A corporation, essentially, is a pile of money to which a number of persons have sold their moral allegiance. Unlike a person, a corporation does not age. It does not arrive, as most persons finally do, at a realization of the shortness and smallness of human lives; it does not come to see the future as the lifetime of the children and grandchildren of anybody in particular.

Wendell Berry (b. 1934) American farmer, educator, poet, conservationist

Essay (2000), “The Total Economy,” Citizenship Papers (2003)

(Source)

CATO: Forbear, Sempronius! — see they suffer death,

But in their deaths remember they are men.

Strain not the laws to make their tortures grievous.Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Cato, Act 3, sc. 5, l. 60ff (1713)

(Source)

In response to Sempronius' plans to torture the captured rebel soldiers before their execution, as an example to others.

SIR THOMAS MORE: Say now the king

(As he is clement, if th’ offender mourn)

Should so much come to short of your great trespass

As but to banish you, whether would you go?

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbor? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, to Spain or Portugal,

Nay, any where that not adheres to England, —

Why, you must needs be strangers. Would you be pleased

To find a nation of such barbarous temper,

That, breaking out in hideous violence,

Would not afford you an abode on earth,

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, nor that the claimants

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But chartered unto them, what would you think

To be thus used? This is the strangers’ case;

And this your mountanish inhumanity.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Sir Thomas More, Act 2, sc. 4, l. 105ff (c. 1592)

(Source)

Quelling rioting Englishmen who were demanding the expulsion of Flemish immigrants, telling them to consider what they themselves might do, and the conditions they might face, if they were forced to leave England.

The play was written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle, with revisions and edits by multiple writers. This particular scene and monologue are in what is considered to be Shakespeare's own hand.

You live through time, that little piece of time that is yours, but that piece of time is not only your own life, it is the summing-up of all the other lives that are simultaneous with yours. It is, in other words, History, and what you are is an expression of History, and you do not live your life, but somehow, your life lives you, and you are, therefore, only what History does to you.

Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989) American poet, novelist, literary critic

Band of Angels, ch. 6 (1955)

(Source)

This is sometimes cited to Warren's World Enough and Time (1950), but is not found there.

Often seen edited down:You live through that little piece of time that is yours, but that piece of time is not only your own life, it is the summing-up of all the other lives that are simultaneous with yours. [...] What you are is an expression of History.

Note that the narrator continues:That is what I have heard said, but we have to try to make sense of what we have lived, or what has lived us, and there are so many questions that cry for an answer, as children gather about your knee and cry for a sweetmeat. No, it would be better to change the comparison and say it is like children gathering about your knee to cry for a story, a bedtime story, and if you can tell the right story, then these children, then these questions, will sleep, and you can, too.

There were times that called for mindless, terror-filled panic, and times that called for measured, considered, thoughtful panic.

And the freedom of the mind, my friends, has served America well. The vigor of our political life, our capacity for change, our cultural, scientific, and industrial achievements, all derive from free inquiry, from the free mind — from the imagination, resourcefulness, and daring of men who are not afraid of new ideas. Most all of us favor free enterprise for business. Let us also favor free enterprise for the mind. For, in the last analysis, we would fight to the death to protect it.

Adlai Stevenson (1900-1965) American diplomat, statesman

Speech (1952-08-27), “The Nature of Patriotism,” American Legion Convention, Madison Square Garden, New York City

(Source)

In his infinite goodness, God invented rheumatism and gout and dyspepsia, cancers and neuralgia, and is still inventing new diseases. Not only this, but he decreed the pangs of mothers, and that by the gates of love and life should crouch the dragons of death and pain. Fearing that some might, by accident, live too long, he planted poisonous vines and herbs that looked like food. He caught the serpents he had made and gave them fangs and curious organs, ingeniously devised to distill and deposit the deadly drop. He changed the nature of the beasts, that they might feed on human flesh. He cursed a world, and tainted every spring and source of joy. He poisoned every breath of air; corrupted even light, that it might bear disease on every ray; tainted every drop of blood in human veins; touched every nerve, that it might bear the double fruit of pain and joy; decreed all accidents and mistakes that maim and hurt and kill, and set the snares of life-long grief, baited with present pleasure, — with a moment’s joy. Then and there he foreknew and foreordained all human tears. And yet all this is but the prelude, the introduction, to the infinite revenge of the good God. Increase and multiply all human griefs until the mind has reached imagination’s farthest verge, then add eternity to time, and you may faintly tell, but never can conceive, the infinite horrors of this doctrine called “The Fall of Man.”

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, freethinker, orator

Lecture (1884-01-20), “Orthodoxy,” Tabor Opera House, Denver, Colorado

(Source)

Published as its own book in 1884.

Religion has treated knowledge sometimes as an enemy, sometimes as a hostage; often as a captive and more often as a child; but knowledge has become of age and religion must either renounce her acquaintance , or introduce her as a companion and respect her as a friend.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon: Or, Many Things in Few Words, Vol. 2, § 141 (1822)

(Source)

Just now, when every one is bound, under pain of a decree in absence convicting them of lèse-respectability, to enter on some lucrative profession, and labour therein with something not far short of enthusiasm, a cry from the opposite party, who are content when they have enough, and like to look on and enjoy in the meanwhile, savours a little of bravado and gasconade. And yet this should not be. Idleness so called, which does not consist in doing nothing, but in doing a great deal not recognized in the dogmatic formularies of the ruling class, has as good a right to state its position as industry itself.

Let the man who has acquired Enough not ask for more.

A house and acreage, a pile of bronze and gold coins,

Have never been able to lower the sick man’s fever

Or drive out his worries. The proprietor must be well

If he plans to enjoy the good things he’s gathered together.[Quod satis est cui contingit, nihil amplius optet.

Non domus et fundus, non aeris acervus et auri

Aegroto doniini deduxit corpore febres,

on animo curas; valeat possessor oportet,

Si conpertatis rebus bene cogitat uti.]Horace (65–8 BC) Roman poet, satirist, soldier, politician [Quintus Horatius Flaccus]

Epistles [Epistularum, Letters], Book 1, ep. 2 “To Lollius,” l. 46ff (1.2.46-50) (14 BC) [tr. Palmer Bovie (1959)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Other translations:He that hath once sufficient, let him wishe for no more:

Not howse nor grove, nor yet of gould, or silver ample store

Can rid the owners crasie corpes fro fellon shaking fever.

Nor can the mynd of man from carke, (for al their vigor) sever:

That owner needes must healthfull bee, and other men excel,

Which hauing riches competent, doth cast to use theim well.

[tr. Drant (1567)]Let him that has enough, desire no more.

Not House and Land, nor Gold and Silver Oare,

The Body's sickness, or the Mind's dispel,

To rellish wealth, the palat must be well.

[tr. Fanshawe; ed. Brome (1666)]He that hath got enough desires no more:

Did ever Lands, or heaps of Silver ease

The feav'rish Lord? Or cool the hot Disease?

Or free his Mind from Cares? He must have health,

He must be well, that would enjoy his wealth.

[tr. Creech (1684)]Blest with a competence, why wish for more?

Nor house, nor lands, nor heaps of labour'd ore

Can give their feverish lord one moment's rest,

Or drive one sorrow from his anxious breast:

The fond possessor must be blest with health,

Who rightly means to use his hoarded wealth.

[tr. Francis (1747)]Nathless who's rich, that is not satisfied? --

Who poor, but he whose wants are unsupplied?

Never did house, or land, or god afford

An hour's short respite to their sickening lord,

Sooth with soft balm the fever's throbbing smart,

Or pluck one rooted sorrow from the heart.

If health be wanting, riches quickly cloy;

'Tis vain to hoard, unless we can enjoy.

[tr. Howes (1845)]He, that has got a competency, let him wish for no more. Not a house and farm, nor a heap of brass and gold, can remove fevers from the body of their sick master, or cares from his mind. The possessor must be well, if he thinks of enjoying the things which he has accumulated.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]Having got

What will suffice you, seek no happier lot.

Not house or grounds, not heaps of brass or gold

Will rid the frame of fever's heat and cold.

Or cleanse the heart of care. He needs good health,

Body and mind, who would enjoy his wealth.

[tr. Conington (1874)]If you've enough, how vain to wish for more!

Nor house, nor lands, nor brass, nor golden store

Can of its fire the fevered frame relieve,

Or make the care-fraught spirit cease to grieve.

Sound, mind and body both, should be his health

To true account who hopes to turn his wealth.

[tr. Martin (1881)]If a sufficiency belong to any one, let him desire no more. A house and farm, a heap of brass and gold, have never removed fever from the sickly body of their possessor, nor cares from his mind. It is a necessity that their owner be sound in body and mind if he contemplate making a good use of his accumulated substance.

[tr. Elgood (1893)]But after all, enough is enough, and he who has enough is wise if he does not ask for more. A house, a farm, and a store of gold, these never drove the fever from their owner's aching body, or took the burden of care from his mind. Verily, the man of wealth must have good health if he would enjoy the fruit of all his labors.

[tr. Dana/Dana (1911)]He, to whose lot sufficient falls, should covet nothing more. No house or land, no pile of bronze or god, has ever freed the owner's sick body of fevers, or his sick mind of cares. The possessor must be sound in health, if he thinks of enjoying the stores he has gathered.

[tr. Fairclough (Loeb) (1926)]But anyone who has enough should want no more.

No house and farm, no heap of copper and gold

can drive a fever from its owner's weakened flesh

Or his worries from his soul. He must be well

if he wants good use from everything he's gathered.

[tr. Fuchs (1977)]But having enough we should never want more. No house

In town, no land, no piles of gold and bronze,

Have ever freed a man's mind, or eased the fevers

Racking his body. To enjoy treasure you must be sound

In mind, stable in body.

[tr. Raffel (1983)]The man who has enough should be satisfied

With what he has. Prosperity is never

Going to be able to cure a body that's sick

Or a mind that's sick. You've got to be well if you want

To enjoy the things you own.

[tr. Ferry (2001)]But when one is blest with enough, one shouldn't long for more.

Possessing a house or farm or a pile of bronze and gold

has never been known to expel a fever from an invalid's body

or a worry from his mind. Unless the owner has sound health

he cannot hope to enjoy the goods he has brought together.

[tr. Rudd (2005 ed.)]But he who’s handed enough, shouldn’t long for more.

Houses and land, piles of bronze and gold, have never

Freed their owner’s sick body from fever, or his spirit

From care: if he wants to enjoy the goods he’s gathered

Their possessor must be well.

[tr. Kline (2015)]

From the beginning men used God to justify the unjustifiable.

She felt that the day should not be bounced in on with rude energy, but carefully and delicately seduced into being, and children and animals were sadly impervious to reason on this matter.

Kerry Greenwood (b. 1954) Australian author and lawyer

Phryne Fisher No. 11, Away with the Fairies, ch. 1 (2001)

(Source)

FAUSTUS. Come, I think hell’s a fable.

MEPHISTOPHILES: Ay, think so still, till experience change thy mind.

Christopher "Kit" Marlowe (1564-1593) English dramatist and poet

The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, Act 2, sc. 1 (sc. 5), l. 573ff (1594; 1604 “A” text)

(Source)

The "B" text (1594; 1616) as a slight variance in Faust's line:FAUSTUS: I think hell's a mere fable.

MEPHISTOPHILES: Aye, think so still, till experience change thy mind.

I’m not going to tell you much more of the case, Doctor. You know a conjurer gets no credit once he has explained his trick; and if I show you too much of my method of working, you will come to the conclusion that I am a very ordinary individual after all.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) British writer and physician

Story (1886-04), “A Study in Scarlet,” Part 1, ch. 4 [Holmes], Beeton’s Christmas Annual, Vol. 28 (1887-11-21)

(Source)

Can the man say, Fiat lux, Let there be light; and out of chaos make a world? Precisely as there is light in himself, will he accomplish this.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

Lecture (1840-05-12), “The Hero as Poet,” Home House, Portman Square, London

(Source)

Talking about Shakespeare and his creativity.

The lecture notes were collected by Carlyle into On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, Lecture 3 (1841).

We are unified both by hating in common and by being hated in common.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 243 (1955)

(Source)

What is the law? A thing that ought neither to be swayed by favor, nor be shattered by force, nor be corrupted by power.

[Quod enim est ius civile? Quod neque inflecti gratia neque perfringi potentia neque adulterari pecunia debeat.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Pro Caecina [For Aulus Caecina], ch. 26 / sec. 73 (c. 69 BC) [tr. @sentantiq (2013)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Other translations:For, indeed, what is the civil law? A thing which can neither be bent by influence, nor broken down by power, nor adulterated by corruption.

[tr. Yonge (1856)]How may we describe it? The law is that which influence cannot bend, nor power break, nor wealth corrupt.

[tr. Grose Hodge (Loeb) (1927)]

I dont know ov enny thing more remorseless, on the face ov the earth, than 7 per cent interest.

[I don’t know of anything more remorseless on the face of the earth than 7 percent interest.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Josh Billings’ Farmer’s Allminax, 1871-03 (1871 ed.)

(Source)

The first sign of corrupt morals is the banishing of truth.

[Le premier traict de la corruption des mœurs, c’est le bannissement de la verité]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 2, ch. 18 (2.18), “Of Giving the Lie [Du Démentir]” (1578–79) [tr. Screech (1987)]

(Source)

This essay (and this passage) appeared in the 1st (1580) edition, and was expanded in each succeeding edition.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:The first part of customs-corruption, is the banishment of truth.

[tr. Florio (1603)]The first step to the corruption of manners is banishing of truth.

[tr. Cotton (1686)]The first thing done in the corruption of manners is banishing truth.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]The first feature of corruption of morals is the banishment of truth.

[tr. Ives (1925)]The first feature in the corruption of morals is the banishment of truth.

[tr. Zeitlin (1934)]The first stage in the corruption of morals is the banishment of truth.

[tr. Frame (1943)]

HUCKLE: As far as we know, the sea was calm and empty.

THE DOCTOR: It may be calm, but it’s never empty.

Doctor Who (1963-1989) British science fiction television series (BBC)

13×01 “Terror of the Zygons,” Part 1 (1975-08-30) [w. Robert Banks Stewart]

(Source)

(Source (Video); dialog confirmed)

The writer whose words are going to be read by children has a heavy responsibility. And yet, despite the undeniable fact that the children’s minds are tender, they are also far more tough than many people realize, and they have an openness and an ability to grapple with difficult concepts which many adults have lost. Writers of children’s literature are set apart by their willingness to confront difficult questions.

Madeleine L'Engle (1918-2007) American writer

Speech (1983-11-16), “Dare To Be Creative,” Lecture, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

(Source)

It is not a bad thing that children should occasionally, and politely, put parents in their place.

[Il n’est pas mauvais que les enfants remettent de temps en temps, avec politesse, les parents à leur place.]

Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873-1954) French writer

My Mother’s House [La Maison de Claudine], “The Priest on the Wall [Le curé sur le mur]” (1922) [tr. Troubridge/McLeod (1949)]

(Source)

Kindness is invincible, if it be sincere and not hypocritical or a mere facade. For what can the most insulting of people do to you if you are consistently kind to him, and, when the occasion allows, gently advise him and quietly put him on the proper course at the very time when he is attempting to do you a mischief. “No, my son, we were born for something other than this; it is not I who am harmed, it is you, my son, who are causing harm to yourself.”

[τὸ εὐμενὲς ἀνίκητον, ἐὰν γνήσιον ᾖ καὶ μὴ σεσηρὸς μηδὲ ὑπόκρισις. τί γάρ σοι ποιήσει ὁ ὑβριστικώτατος, ἐὰν διατελῇς εὐμενὴς αὐτῷ καί, εἰ οὕτως ἔτυχε, πρᾴως παραινῇς καὶ μεταδιδάσκῃς εὐσχολῶν παῤ αὐτὸν ἐκεῖνον τὸν καιρὸν ὅτε κακοποιεῖν σε ἐπιχειρεῖ: ῾μή, τέκνον: πρὸς ἄλλο πεφύκαμεν. ἐγὼ μὲν οὐ μὴ βλαβῶ, σὺ δὲ βλάπτῃ, τέκνον.᾿]

Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180) Roman emperor (161-180), Stoic philosopher

Meditations [To Himself; Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν], Book 11, ch. 18 (11.18) (AD 161-180) [tr. Hard (1997 ed.)]

(Source)

Marcus' 9th point to remember when aggravated by another's actions. Graves comments, "The good Emperor, I am afraid, had too good an opinion of human nature in general."

Hard uses the same translation in their 2011 edition.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Meekness is a thing unconquerable, if it be true and natural, and not affected or hypocritical. For how shall even the most fierce and malicious that thou shalt conceive, be able to hold on against thee, if thou shalt still continue meek and loving unto him; and that even at that time, when he is about to do thee wrong, thou shalt be well disposed, and in good temper, with all meekness to teach him, and to instruct him better? As for example; My son, we were not born for this, to hurt and annoy one another; it will be thy hurt not mine, my son.