Precisely because the tyranny of opinion is such as to make eccentricity a reproach, it is desirable, in order to break through that tyranny, that people should be eccentric. Eccentricity has always abounded when and where strength of character has abounded; and the amount of eccentricity in a society has generally been proportional to the amount of genius, mental vigor, and more courage it contained. That so few dare to be eccentric marks the chief danger of the time.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) English philosopher and economist

On Liberty, ch. 3 “Of Individuality, as One of the Elements of Well-Being” (1859)

(Source)

Quotations about:

eccentricity

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Queerly shaped pieces of flat silver, contrived for purposes known only to their designers, have no place on a well appointed table. So if you use one of these implements for a purpose not intended, it cannot be a breach of etiquette, since etiquette is founded on tradition, and has no rules concerning eccentricities.

Emily Post (1872-1960) American author, columnist [née Price]

Etiquette: The Blue Book of Social Usage, ch. 37 “Flat Silver” (1922; 1927 ed.)

(Source)

The world today does not understand, in either man or woman, the need to be alone. How inexplicable it seems. Anything else will be accepted as a better excuse. If one sets aside time for a business appointment, a trip to the hairdresser, a social engagement or a shopping expedition, that time is accepted as inviolable. But if one says: I cannot come because that is my hour to be alone, one is considered rude, egotistical or strange. What a commentary on our civilization, when being alone is considered suspect; when one has to apologize for it, make excuses, hide the fact that one practices it — like a secret vice!

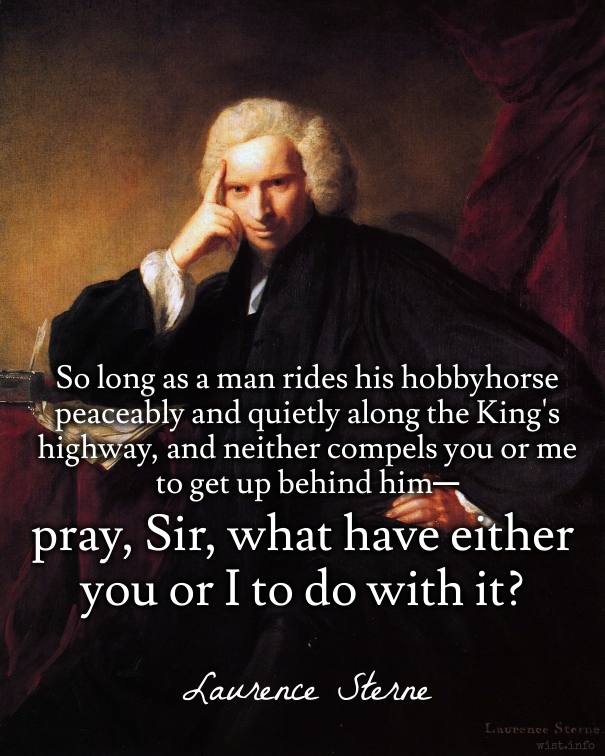

So long as a man rides his hobbyhorse peaceably and quietly along the King’s highway, and neither compels you or me to get up behind him — pray, Sir, what have either you or I to do with it?

The first thing to learn in intercourse with others is non-interference with their own peculiar ways of being happy, provided those ways do not assume to interfere by violence with ours.

William James (1842-1910) American psychologist and philosopher

“What Makes a Life Significant,” Lecture, Harvard (1899)

Reprinted in Talks to Teachers on Psychology, Part 2, Lecture 3.

There is one characteristic of the present direction of public opinion peculiarly calculated to make it intolerant of any marked demonstration of individuality. The general average of mankind are not only moderate in intellect, but also moderate in inclinations; they have no tastes or wishes strong enough to incline them to do anything unusual, and they consequently do not understand those who have, and class all such with the wild and intemperate whom they are accustomed to look down upon.