We should keep silent about those in power; to speak well of them almost implies flattery; to speak ill of them while they are alive is dangerous, and when they are dead is cowardly.

[L’on doit se taire sur les puissants: il y a presque toujours de la flatterie à en dire du bien; il y a du péril à en dire du mal pendant qu’ils vivent, et de la lâcheté quand ils sont morts.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 9 “Of the Great [Des Grands],” § 56 (9.56) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

The less we talk of the powerful, the better; what we say good of them, is often flattery: 'Tis dangerous to speak ill of 'em while they live, and villainous when they are dead.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]

The less we talk of the Great and Powerful, the better; what good we say of them is often Flattery 'Tis dangerous to speak ill of them while they are alive, and villainous when dead.

[Curll ed. (1713)]

The less we talk of the Great and Powerful, the better; what good we say of them is often Flattery: It is dangerous to speak of of them while living, it is base to insult over them when dead.

[Browne ed. (1752)]

The less we talk of the great and powerful the better; if we say any good of them, it is often almost flattery; it is dangerous to speak ill of them whilst they are alive, and cowardly when they are dead.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

Quotations about:

criticism

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Perhaps the greatest rudenesses of our time come not from the callousness of strangers, but from the solicitousness of intimates who believe that their frank criticisms are always welcome, and who feel free to “be themselves” with those they love, which turns out to mean being their worst selves, while saving their best behavior for strangers.

Judith Martin (b. 1938) American author, journalist, etiquette expert [a.k.a. Miss Manners]

Common Courtesy, “Those Who Would Change the Country’s Manners Encounter Citizen Resistance” (1985)

(Source)

ADRIANA: He is deformèd, crooked, old, and sere,

Ill-faced, worse-bodied, shapeless everywhere,

Vicious, ungentle, foolish, blunt, unkind,

Stigmatical in making, worse in mind.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Comedy of Errors, Act 4, sc. 2, l. 21ff (4.2.21-24) (1594)

(Source)

Doubtless we’re all mistaken so — ’tis true,

Each is in something a Suffenus too:

Our neighbour’s failing on his back is shown,

But we don’t see the wallet on our own.[Nimirum idem omnes fallimur, neque est quisquam

quem non in aliqua re videre Suffenum

possis. Suus cuique attributus est error,

sed non videmus manticae quod in tergo est.]Catullus (c. 84 BC – c. 54 BC) Latin poet [Gaius Valerius Catullus]

Carmina # 22 “To Varus,” ll. 18-21 [tr. Cranstoun (1867)]

(Source)

Discussing Suffenus, a prolific (but very mediocre) poet, who believes himself to be extremely clever and talented. The metaphor in the last few lines reference Aesop's fable of the two bags.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Yet all to such errors are prone, I believe;

Each man in himself a Suffenus may find:

The failings of others we quickly perceive,

But carry our own imperfection behind.

[tr. Nott (1795), # 19]

Yet we are all, I doubt, in truth

Deceived like this complacent youth;

All, I am much afraid, demean us

In some one thing just like Suffenus.

For still to every man that lives

His share of errors Nature gives;

But they, as 'tis in fable sung,

Are in a bag behind us hung;

And our formation kindly lacks

The power to see behind our backs.

[tr. Lamb (1821)]

Yet, which of us is there but makes

About himself as odd mistakes?

In some one thing we all demean us

Not less absurdly than Suffenus;

For vice or failing, small or great,

Is dealt to every man by fate.

But in a wallet at our back

Do we our peccadilloes pack,

And, as we never look behind,

So out of sight is out of mind.

[tr. T. Martin (1861)]

Friend, 'tis the common error; all alike are wrong,

Not one, but in some trifle you shall eye him true

Suffenus; each man bears from heaven the fault they send,

None sees within the wallet hung behind, our own.

[tr. Ellis (1871)]

In sooth, we all thus err, nor man there be

But in some matter a Suffenus see

Thou canst: his lache allotted none shall lack

Yet spy we nothing of our back-borne pack.

[tr. Burton (1893)]

Still, we are all the same and are deceived, nor is there any man in whom you can not see a Suffenus in some one point. Each of us has his assigned delusion: but we see not what's in the wallet on our back.

[tr. Smithers (1894)]

True enough, we all are under the same delusion, and there is no one whom you may not see to be a Suffenus in one thing or another. Everybody has his own fault assigned to him: but we do not see that part of the bag which hangs on our back.

[tr. Warre Cornish (1904)]

After all, every man of us is deceived in the same way, nor is there any one in whom, in some trait or another, you cannot recognize a Suffenus. Every one has his weak point, but we do not see what lies in that part of our wallet which is behind our backs.

[tr. Stuttaford (1912)]

Sure, all men into some such error fall,

There's a Suffenus in us one and all,

Each has his proper fault and each is blind

To the wallet's other half that hangs behind.

[tr. MacNaghten (1925)]

Have we not all some faults like these?

Are we not all Suffenuses?

In others the defect we find,

But cannot see our sack behind.

[tr. Landor (c. 1926)]

And we (all of us) have the same rich glow, the rapture

when writing verse. And there is no one living

who cannot find within him something of Suffenus,

each his hallucination that blinds him,

nor can he nor his sharp eyes discover

the load on his own shoulders.

[tr. Gregory (1931)]

Well, we all fall this way! There's not a person

whom in some matter you can fail to see

to be Suffenus. We cart round our follies,

but cannot see the bags upon our backs.

[tr. Fraser (1961)]

Conceited? Yes, but show me a man who isn't:

someone who doesn't seem like Suffenus in something.

A glaring fault? It must be somebody else's:

I carry mine in my backpack & ignore them.

[tr. C. Martin (1979)]

Of course we’re all deceived in the same way, and

there’s no one who can’t somehow or other be seen

as a Suffenus. Whoever it is, is subject to error:

we don’t see the pack on our own back.

[tr. Kline (2001)]

Clearly we are all deceived in the same way, nor is there anyone

Whom you could see not to be Suffenus in some thing.

To each one of us one's own mistakes have been assigned;

but we do not see the knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Drudy (1997)]

Ah well, we all make that mistake -- there's not

one of us whom you can't in some small way

see as Suffenus. Each reveals his inborn flaw --

and yet we're blind to the load on our own backs!

[tr. Green (2005)]

Evidently we all falter in the same way, and there is no one

whom you cannot see Suffenus in some fashion.

To each man is attributed his own error;

but we do not see the kind of knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Wikibooks (2017)]

Evidently we all are deceived the same way, nor is there anyone

whom you are not able to see Suffenus in some way.

To each their own error has been assigned;

but we do not see the knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Wikisource (2018)]

Pride plays a greater part than kindness in our censure of a neighbor’s faults. We criticize faults less to correct them, than to prove that we do not possess them.

[L’orgueil a plus de part que la bonté aux remontrances que nous faisons à ceux qui commettent des fautes; et nous ne les reprenons pas tant pour les en corriger que pour leur persuader que nous en sommes exempts.]

François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) French epigrammatist, memoirist, noble

Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales [Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims], ¶37 (1665-1678) [tr. Heard (1917)]

(Source)

Present from the first edition. (Source (French)). Alternate translations:

We are liberal of our remonstrances and reprehensions towards those, whom we think guilty of miscarriages; but we therein betray more pride, than charity. Our reproving them does not so much proceed from any desire in us of their reformation, as from an insinuation that we our selves are not chargeable with the like faults.

[tr. Davies (1669), ¶142]

Pride hath a greater share than Goodness in the reproofs we give other people for their faults; and we chide them, not so much with a design to mend them, as to make them believe that we ourselves are not guilty of them.

[tr. Stanhope (1694), ¶38]

Pride is more concerned than benevolence in our remonstrances to persons guilty of faults; and we reprove them not so much with a design to correct, as to make them believe that we ourselves are free from such failings.

[pub. Donaldson (1783), ¶349; ed. Lepoittevin-Lacroix (1797), ¶37]

In our reprehensions, pride has a greater share than good nature. We reprove, not so much in order to correct, as to intimate that we hold ourselves free from such failings.

[ed. Carville (1835), ¶309]

Pride has a greater share than goodness of heart in the remonstrances we make to those who are guilty of faults; we reprove not so much with a view to correct them as to persuade them that we are exempt from those faults ourselves.

[ed. Gowens (1851), ¶38]

Pride has a larger part than goodness in our remonstrances with those who commit faults, and we reprove them not so much to correct as to persuade them that we ourselves are free from faults.

[tr. Bund/Friswell (1871), ¶37]

Pride, rather than virtue, makes us reprove those who have done wrong; our reproaches are not so much intended to improve the evil-doer, as to show him that we are quite free of his taint.

[tr. FitzGibbon (1957), ¶37]

Pride plays a greater part than kindness in our remonstrating with those who make mistakes; and we point out their faults, less to correct them than to indicate they are not ours.

[tr. Kronenberger (1959), ¶37]

Pride plays a greater part than kindness in the reprimands we address to wrongdoers; we reprove them not so much to reform them as to make them believe that we are free from their faults.

[tr. Tancock (1959), ¶37]

Pride shares a greater part than the goodness of our hearts in the reprimands we give to those who commit faults; and we do not reprove so much in order to correct them, as in order to persuade them that we are ourselves exempt from those faults.

[tr. Whichello (2016), ¶37]

O the times! O the manners!

[O tempora, o mores!]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Orationes in Catilinam [Catilinarian Orations], No. 1, § 1, cl. 2 (1.1.2) (63-11-08 BC) [tr. Mongan (1879)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Oh what times! what a world do we live in!

[tr. Wase (1671)]

But O degenerate times!

[tr. Sydney (1795)]

Shame on the age and on its principles!

[tr. Yonge (1856)]

O the times! O the manners.

[tr. Underwood (1885)]

O times! O manners!

[tr. Dewey (1916)]

What a scandalous commentary on our age and its standards!

[tr. Grant (1960)]

O what times (we live in)! O what customs (we pursue)!

[IB Notes]

What times! What morals!

[Source]

There is really no way of considering a book independently of one’s special sensations in reading it on a particular occasion. In this as in everything else one must allow a certain relativity. In a sense, one can never read the book that the author originally wrote, and one can never read the same book twice.

Edmund Wilson, Jr. (1895-1972) American writer, literary critic, journalist

The Triple Thinkers, Foreword (1948 ed.)

(Source)

The writer who considers only the taste of his own time is concerned more with his personal fame than with that of his books: we should always aim at perfection, and then we shall receive from posterity that justice which our contemporaries sometimes deny us.

[Celui qui n’a égard en écrivant qu’au goût de son siècle songe plus à sa personne qu’à ses écrits: il faut toujours tendre à la perfection, et alors cette justice qui nous est quelquefois refusée par nos contemporains, la postérité sait nous la rendre.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 1 “Of Works of the Mind [Des Ouvrages de l’Esprit],” § 67 (1.67) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

He who regards nothing more in his Works than the taste of the Age, has a greater value for his Person than his Writings: He should always aim at Perfection; and tho his Contemporaries refuse him Justice, Posterity will give it him.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]

He who regards nothing more in his Works than the Taste of his own Age, Considers his Person more than his Writings: He should always aim at Perfection, and tho his Contemporaries refuse him Justice, Posterity will give it him.

[Curll ed. (1713)]

He who regards nothing more in his Works than the Taste of the Age, has a greater value for his Person than his Writings: He should always aim at Perfection; and though his Cotempararies refuse him Justice, he will be better used by Posterity.

[Browne ed. (1752)]

He who only writes to suit the taste of the age, considers himself more than his writings. We should always aim at perfection, and then posterity will do us that justice which sometimes our contemporaries refuse.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

If, as certain small-minded philosophers believe, I shall feel nothing at all after death, then at least I don’t have to worry that they will be there to mock me after they die!

[Sin mortuus, ut quidam minuti philosophi censent, nihil sentiam, non vereor ne hunc errorem meum philosophi mortui irrideant.]Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 23 / sec. 85 (23.85) (44 BC) [tr. Freeman (2016)]

(Source)

Critiquing the Epicurians, who would disagree with his belief in an immortal soul.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

For if aftir this presente life I be dede as wele in soule as in body as that some yong and smale philosophers of whiche men name Epycures that affermyn, Certayne it is that I shall feele nothyng. And also I am not afferde that suche philosophers so ded mockyn me nor of this myne oppinion. Aftir whiche I verily beleve that the soules be undedly.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]

And if it were not so, that after death I should feel nothing nor have any sense at all (as certain perrifoggers and bastard philosophers hold opinino) I fear not a whit least these lip-labourers and ideitical philosophers, when they themselves be dead, should scoff and make a mocking-stock at this mine assertion and belief, because they themselves shall also be without sense, and like to brute beasts.

[tr. Newton (1569)]

But if when I am dead (as some small Philosophers say) I shall feel nothing, I fear not least the dead Philosophers should laugh at this my error.

[tr. Austin (1648)]

If those who this Opinion have despis'd,

And their whole life to pleasure sacrific'd;

Should feel their error, they when undeceiv'd,

Too late will wish, that me they had believ'd.

[tr. Denham (1669)]

But if after this Life I shall no longer be sensible, as some little Philosophers imagine, then am I in no Fear that dead Philosophers will laugh at my mistaken Opinion.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

And if, when dead, I should (as some minute Philosophers imagine) be deprived of all further Sense, I am safe at least in this, that those Blades themselves will have no Opportunity beyond the Grave to laugh at me for my Opinion.

[tr. Logan (1744)]

I have the satisfaction in the meantime to be assured that if death should utterly extinguish my existence, as some minute philosophers assert, the groundless hope I entertained of an after-life in some better state cannot expose me to the derision of these wonderful sages, when they and I shall be no more.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

But if (as certain super-subtle philosophers conclude) I shall feel nothing, I am not afraid lest these philosophers, when dead, should ridicule this error of mine.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

But if I, when dead, shall have no consciousness, as some narrow-minded philosophers imagine, I do not fear lest dead philosophers should ridicule this my delusion.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

While if in death, as some paltry philosophers think, I shall have no consciousness, the dead philosophers cannot ridicule this delusion of mine.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

But if when dead, as some insignificant philosophers think, I am to be without sensation, I am not afraid of dead philosophers deriding my errors.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

But if when dead;

As some philosophers of little note

Believe, I feel no more, there is no fear

These dead philosophers should mock me there.

[tr. Allison (1916)]

But if when dead I am going to be without sensation (as some petty philosophers think), then I have no fear that these seers, when they are dead, will have the laugh on me!

[tr. Falconer (1923)]

True, certain insignificant philosophers hold that I shall feel nothing after death. If so, then at least I need not fear that after their own deaths they will be able to mock my conviction!

[tr. Grant (1960, 1971 ed.)]

If on the other hand, as certain petty philosophers have held, I shall have no sensation when I am dead, then I need have no fear that deceased philosophers will make fun of this delusion of mine.

[tr. Copley (1967)]

Some second-rate philosophers suggest that when I am dead I will be conscious of nothing. But all that means is that, if I’m wrong, they won't be able to make fun of me after their death.

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]

But anyway, if when I die my spirit also dies, I certainly won't give a flip about the opinions of dead philosophers.

[tr. Gerberding (2014)]

If when I am dead I’ll have no sensation,

As some small philosophers think, I won’t fear

Accents of derision from their graves to hear.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

A man must serve his time to every trade

Save Censure — Critics all are ready made.George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) English poet

“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,” l. 63ff (1809)

(Source)

Some thirty poems in the book

Are poor, you say. Egad!

If you’ve found thirty good ones, too,

The book is great, not bad.[‘Triginta toto mala sunt epigrammata libro.’

Si totidem bona sunt, Lause, bonus liber est.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 7, epigram 81 (7.81) (AD 92) [tr. Marcellino (1968)]

(Source)

"To Lausus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thou thirty epigrams dost note for bad:

Call my book good if thirty good it had.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

For thirty bad epigrams here you may look:

If as many good ones, it is a good book.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 7]

In this whole book there are thirty bad epigrams; if there as many good ones, Lausus, the book is good.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

"Take all your book, and there are thirty bad epigrams in it." If as many are good, Lausus, the book is a good one.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You’ve read my poems and condemn

Some thirty, so you say, of them:

The book’s a good one I submit,

If there are thirty good in it.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "Proportions"]

"There are thirty bad epigrams

in your book, at least."

If there are that many good ones,

Lausus, I'll be pleased.

[tr. Bovie (1970), mislabeled 7.18]

"There are thirty bad epigrams in the whole book." If there as many good ones, Lausus, it's a good book.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

"Your book as thirty epigrams unneeded."

I've only thirty clunkers? I've succeeded.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

"In this book, thirty poems are bad," you state.

Lausus, if thirty are good, the book is great.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You can’t beat an Administration by attacking it. You have to show some plan of improving on it.

It is as unreasonable in any one Man or Set of Men to expect to be pleas’d with every thing that is printed, as to think that nobody ought to be pleas’d but themselves.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

“Apology for Printers,” Philadelphia Gazette (1731-06-10)

(Source)

The way to achieve happiness is to have a high standard for yourself and a medium one for everyone else.

Marcelene Cox (1900-1998) American writer, columnist, aphorist

“Ask Any Woman” column, Ladies’ Home Journal (1954-08)

(Source)

One sure way to lose another woman’s friendship is to try to improve her flower arrangements.

Marcelene Cox (1900-1998) American writer, columnist, aphorist

“Ask Any Woman” column, Ladies’ Home Journal (1948-02)

(Source)

This was a regularly revisited aphorism for Cox:

One sure way to lose another woman's friendship is to try to improve her husband.

(1955-12)

The quickest way to lose another woman's friendship is to endeavor to improve her husband, her children, or her flower arrangements.

(1959-05)

One sure way to lose another woman's friendship is to try to improve either her children or her flower arrangements.

(1961-07)

Whereas I formerly believed it to be my bounden duty to call others to order, I must now admit that I need calling to order myself, and that I would do better to set my own house to rights first.

Carl Jung (1875-1961) Swiss psychologist

“The Spiritual Problem of Modern Man,” ¶ 162 (1928)

(Source)

Bad reviews jar me down to the instep. I will never become philosophically resigned to a negative reaction to something I’ve written.

Rod Serling (1924-1975) American screenwriter, playwright, television producer, narrator

Patterns, Introduction (1957)

(Source)

The First Amendment means to me, however, that the only constitutional way our Government can preserve itself is to leave its people the fullest possible freedom to praise, criticize or discuss, as they see fit, all governmental policies and to suggest, if they desire, that even its most fundamental postulates are bad and should be changed.

Hugo Black (1886-1971) American politician and jurist, US Supreme Court Justice (1937-71)

Barenblatt v. United States, 360 U.S. 109, 145-46 (1959) [dissent]

(Source)

Persons of today praise the things of yesterday, and those here the things there. Everything past seems best and everything distant is more valued.

[También alaban los de hoy las cosas de ayer, y los de acá las de allende. Todo lo pasado parece mejor, y todo lo distante es más estimado.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 209 (1647) [tr. Jacobs (1892)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:

Modern men praise ancient things, and those that are here, things that are there. All that's past seems best, and all that's remote is most esteemed.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]

People of today praise things of yesterday, and those who are here, the things that are there. The past seems better, and everything distant is held more dear.

[tr. Maurer (1992)]

They of today glorify only things of yesterday, and those from here only the things from afar. Or that all that is past is better, and everything that is distant, more valuable.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

The usual devastating put-downs imply that a person is basically bad, rather than that he is a person who sometimes does bad things. Obviously, there is a vast difference between a “bad” person and a person who does something bad.

Hilary Hinton "Zig" Ziglar (1926-2012) American author, salesperson, motivational speaker

See You at the Top, Segment 2, ch. 2 “Causes of a Poor Self Image” (1974)

(Source)

Matho alleges that my book’s uneven.

He compliments my poems, if that’s true.

Calvinus and Umber write consistent books.

Consistent books are lousy through and through.[Iactat inaequalem Matho me fecisse libellum:

Si verum est, laudat carmina nostra Matho.

Aequales scribit libros Calvinus et Umber:

Aequalis liber est, Cretice, qui malus est.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 7, epigram 90 (7.90) (AD 92) [tr. McLean (2014)]

(Source)

"To Creticus" (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Matho objects, my books unequal are;

If he says true, he praises ere aware.

Calvin and Umber write an equal strain:

Naught is the book that's free from heights, and plain.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

My book is unequal, a Matho may boast.

So saying, he knows not he cries it up most.

Books equal a Calvin and Umber did write;

But equally penn'd in poor Pallasses spite.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 3, ep. 15]

Matho exults that I have produced a book full of inequalities; if this be true, Matho only commends my verses. Books without inequalities are produced by Calvinus and Umber. A book that is all bad, Creticus, may be all equality.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

I've writ, says Matho, an uneven book:

If that be true, then Matho lauds my verse.

Umber writes evenly, Calvinus too;

For even books, to be sure, are always bad.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Matho puts it abroad that I have composed an unequal book; if that is true, Matho praises my poems. Equal books are what Calvinus and Umber write: the equal book, Creticus, is the bad one.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

My work's uneven, you protest

And sometimes falls beneath my best;

A compliment, say I:

Dull bards on level planes that grope

Shall never err -- or soar -- with Pope,

Although they shine with Pye.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "The Dull Level"]

I write unequal verse, so Matho says;

If it be true his criticism's a praise.

Try Umber, Cluveienus by that test:

No, Creticus; bad's bad; good seldom best.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #382]

Matho exults and crows my book's uneven.

If that is true, he praises me. I'm glad.

Calvinus and Umber write books that are even.

Even books are books that are all bad.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Matho's mad,

upset,

says my book

is unfair.

That's good,

I'm glad:

fair books

are dull books.

[tr. Goertz (1971)]

Matho spreads the word that I have made an uneven book. If so, Matho praises my poems. Calvinus adn Umber write even books. An even book, Creticus, is a bad book.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Matho says my book's uneven.

He thinks he's quite the joker.

I'd rather have both highs and lows,

Than just be mediocre.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

Matho's one-word review of my small book:

"Uneven." I'm supposed to get all shook!

The scribblings of Calvinus and Umber

Are very "even" ... yet how they lumber.

I swear to you, Creticus, I thank God

My gift is for being quite frankly "odd."

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

Dour Matho offers me a "mixed review,"

To which contentedly I answer, "Whew!"

Most poets get reviews that are unmixed,

With every verse and stanza in them nixed.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Smootus says my book is uneven.

I see this as praise of my work.

A bad book is fat with unvarying quality.

[tr. Kennelly (2008)]

Matho is crowing that I've "made an inconsistent book." If he's right, he's actually praising my poems. Calvinus and Umber write "consistent" books; if a book's "consistent," Creticus, it's consistently bad.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

We should be sure, when we rebuke a want of charity, to do it with charity.

Christian Nestell Bovee (1820-1904) American epigrammatist, writer, publisher

Intuitions and Summaries of Thought, Vol. 1, “Charity” (1862)

(Source)

“Write shorter epigrams,” is your advice.

Yet you write nothing, Velox. How concise![Scribere me quereris, Velox, epigrammata longa.

Ipse nihil scribis: tu breviora facis.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 110 (1.110) (AD 85-86) [tr. McLean (2014)]

(Source)

"To Velox." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Velox complains my epigrams are long,

When he writes none: he sings a shorter song.

[tr. Fletcher (c. 1650)]

You say my epigrams, Velox, too long are:

You nothing write; sure yours are shorter far.

[tr. Wright (1663)]

Of my long epigrams, you, Swift, complain;

And nothing write: I laud your shorter strain.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 16, "To Velox, or Swift"]

You complain, Velox, that the epigrams which I write are long. You yourself write nothing; your attempts are shorter.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

You complain, Velox, that I write long epigrams, you yourself write nothing. Yours are shorter.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

"Such lengthy epigrams," you say, "affright one."

True, yours are shorter, for you never write one.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Velox, I make my epigrams too long, you snort?

You don't write any: That's making them too short.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Velox, you complain that I write long epigrams, and yourself write nothing. Do you make shorter ones?

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You say I write lines longer than I ought?

It's true your lines are shorter -- they are nought.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

You say my epigrams are too long.

Yours are shorter.

You write nothing.

[tr. Kennelly (2008), "Nothing"]

Swifty, you moan that I write long epigrams. You aren't writing anything yourself; is that you making shorter ones?

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

My epigrams are word, you've complained;

But you write nothing. Yours are more restrained.

[tr. O'Connell]

“Much too long” you say, Velox, censorious,

Of my epigrams -- that’s quite uproarious.

You write none. Your brevity is glorious.

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

You call my epigrams verbose and lacking in concision

while you yourself write nothing. Wise decision.

[tr. Clark, "Short Enough?"]

My epigrams are wordy, you’ve complained;

But you write nothing. Yours are more restrained.

[tr. Oliver]

You damn every poem I write,

Yet you won’t publish those of your own.

Now kindly let yours see the light,

Or else leave my damned ones alone.[Cum tua non edas, carpis mea carmina, Laeli.

Carpere vel noli nostra vel ede tua.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 91 (1.91) (AD 85-86) [tr. Nixon (1911)]

(Source)

"To Lælius". (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thou blam'st my verses and conceal'st thine own:

Or publish thine, or else let mine alone!

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

You do not publish your own verses, Laelius; you criticise mine. Pray cease to criticise mine, or else publish your own.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Although you don't publish your own, you carp at my poems, Laelius. Either do not carp at mine, or publish your own.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You blame my verse; to publish you decline;

Show us your own or cease to carp at mine.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Although you have not published

Even a single line

Of poetry yourself, you scoff

And sneer and jeer at mine.

Get off my back or publish!

I'd like to hear you whine!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Although you don't punish anything, Laelius,

you keep finding fault with my songs. So please,

stop criticizing my stuff, or publish your own.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Although you don't publish your own poems, Laelius, you carp at mine. Either don't carp at mine or publish your own.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Each poem I publish you loudly bemoan.

Unfair that you never share works of your own.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

You don’t write poems, Laelius, you criticise mine. Stop criticising me or write your own.

[tr. Kline (2006)]

With carpings you my works revile.

Your own you never publish.

Without such works, your carpings I'll

Consider snooty rubbish.

[tr. Wills (2007), "The Critic"]

You blast my verses, Laelius; yours aren’t shown.

Either don’t carp at mine or show your own.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You won’t reveal your verse,

but whine that mine is worse.

Just leave me alone

or publish your own.

[tr. Juster (2016)]

You never wrote a poem,

yet criticize mine?

Stop abusing me or write something fine

of your own!

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]

But if our democracy is to flourish it must have criticism, if our government is to function it must have dissent. Only totalitarian governments insist upon conformity and they — as we know — do so at their peril. Without criticism abuses will go unrebuked; without dissent our dynamic system will become static. The American people ‘have a stake in the maintenance of the most thorough-going inquisition into American institutions. They have a stake in nonconformity, for they know that the American genius is nonconformist.

In the verse Cinna writes

I am slandered, it’s said.

But the man doesn’t write

Whose verses aren’t read.[Versiculos in me narratur scribere Cinna.

Non scribit, cuius carmina nemo legit.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 3, epigram 9 (3.9) (AD 87-88) [tr. Nixon (1911)]

"On Cinna." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Cinna writes verses against me, 'tis said:

He writes not, whose bad verse no man doth read.

[tr. Fletcher (c. 1650)]

Against me Cinna, as I hear, indites;

Since none him reads, who can affirm he writes?

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Cinna's verse upon me, they say, keenly procedes.

He's beli'd: for he writes not, whom nobody reads.

[tr. Elphinston (1782). 12.23]

Jack writes severe lampoons on me, 'tis said

----But he writes nothing, who is never read.

[tr. Hodgson (c. 1810)]

Cinna, I am told, is a writer of small squibs against me. A man cannot be called a writer, whose effusions no one reads.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Cinna, they say, 'gainst me is writing verses:

He can't be said to write whom no one reads.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Cinna is said to write verses against me. He doesn't write at all whose poems no man reads.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

He publishes lampoons on me, 'tis said;

How can he publish who is never read?

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Cinna writes poems against me? He has no readers,

so how can they say that he's a writer?

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Cinna is reported to write verses against me. Nobody writes, whose poems nobody reads.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Cinna, a writer, attacks me with screeds.

But he's not a writer whom nobody reads.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

They say Cinna writes little poems about me.

He’s no writer, whose verse nobody reads.

[tr. Kline (2006), "A Silent Critic"]

His verse was meant to strike me low,

But since he wrote it -- who will know?

[tr. Wills (2007)]

I hear Cinna has written some verses against me.

A man is no writer

if his poems have no reader.

[tr. Kennelly (2008)]

Cinna, they say, writes verse attacking me.

He doesn’t write, whose verses none will see.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

They say Cinna is writing epigrams and I'm his target. He's not "writing" if no one's reading him.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

They say that Cinna slams

me in his epigrams.

A poem no one has heard

has really not occurred.

[tr. Juster (2016)]

Cinna attacks me, calls me dirt?

Let him. Who isn't read, can't hurt.

[tr. O'Connell]

We do not protect freedom in order to indulge error. We protect freedom in order to discover truth. We do not maintain freedom in order to permit eccentricity to flourish; we maintain freedom in order that society may profit from criticism, even eccentric criticism. We do not encourage dissent for sentimental reasons; we encourage dissent because we cannot live without it.

Henry Steele Commager (1902-1998) American historian, writer, activist

“The Necessity of Freedom,” Freedom, Loyalty, Dissent (1954)

(Source)

An earlier version of the essay was given as "The Pragmatic Necessity for Freedom," Cooper Lecture, Swarthmore College (1951).

Reader and hearer, Aulus, love my stuff;

A certain poet says it’s rather rough.

Well, I don’t care. For dinners or for books

The guest’s opinion matters, not the cook’s.[Lector et auditor nostros probat, Aule, libellos,

Sed quidam exactos esse poeta negat.

Non nimium curo: nam cenae fercula nostrae

Malim convivis quam placuisse cocis.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 9, epigram 81 (9.81) (AD 94) [tr. Francis & Tatum (1924)]

(Source)

"To Aulus". The numbering for this epigram varies between 81, 82, and 83 within in Book 9. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

The readers and the hearers like my books,

And, yet, some writers cannot them digest:

But what care I? for when I make a feast,

I would my guests should praise it, not the cooks.

[tr. Harington (16th C)]

Readers and hearers, both my Bookes renowne;

Some Poets say th' are not exactly done.

I care not much; like banquets, let my Bookes

Rather be pleasing to the guests than Cookes.

[tr. May (1629), 9.82]

My works the reader and the hearer praise:

They're not exact; a brother poet says:

I heed not him; for when I give a feast,

Am I to please the cook, or please the guest?

[tr. Hay (1755), ep. 82]

The reader and the hearer like my lays.

But they're unfinisht things, a poet says.

The stricture ne'er shall discompose my looke:

My chear is for my guests, and not for cooks.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 3.14]

My works the reader and the hearer praise; --

They're incorrect, a brother poet says:

But let him rail; for when I give a feast,

Am I to praise the cook, or please the guest?

[tr. Hoadley (fl. 18th C), 9.82, §255]

The reader and the hearer approve of my small books, but a certain critic objects that they are not finished to a nicety. I do not take this censure much to heart, for I would wish that the course of my dinner should afford pleasure to guests rather than to cooks.

[tr. Amos (1858) 2.24]

My readers and hearers, Aulus, approve of my compositions; but a certain critic says that they are not faultless. I am not much concerned at his censure; for I should wish the dishes on my table to please guests rather than cooks.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Reader and hearer both my verses praise:

Some other poet cries, "They do not scan."

But what care I? my dinner's always served

To please my guests, and not to please the cooks.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Though my readers sincerely admire me,

A poet finds fault with my books.

What's the odds? When I'm giving a dinner

I'd rather please guests than the cooks.

[tr. Nixon (1911)]

Reader and hearer approve of my works, Aulus, but a certain poet says they are not polished. I don't care much, for I should prefer the courses of my dinner to please guests rather than cooks.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

"Unpolished" -- so that scribbler sneers,

While he that reads and he that hears,

Approve my little books;

I do not care a single jot,

My fame is for my guests and not

To please my rival cooks.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

The public likes my poems, though

A certain poet thinks them rough

Or never polished quite enough.

I could not care less! I prefer

The morsels served up in my books

To please my guests, not would-be cooks.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Readers and listeners like my books,

Yet a certain poet calls them crude.

What do I care? I serve up food

To please my guests, not fellow cooks.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Everyone enjoys my delightful books

Except a certain poet who objects.

I aim to please my guests, not other cooks.

[tr. O'Connell (1991)]

Reader and listener approve my little books, Aulus, but a certain poet says they lack finish. I don't care too much; for I had rather the courses at my dinner pleased the diners than the cooks.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Read or recited, my verse is much praised,

Aulus, yet one poet opines: "Ill-phrased."

I couldn't care less! When I set a table,

My guests, not the cooks, should say I'm able.

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

My books are praised by him who reads,

Though critics damn them in their screeds.

But who's to judge a proper meat --

Another cook, or those who eat?

[tr. Wills (2007), ep. 83]

It is advantageous to an author, that his book should be attacked as well as praised. Fame is a shuttlecock. If it be struck at one end of the room, it will soon fall to the ground. To keep it up, it must be struck at both ends.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) English writer, lexicographer, critic

Comment (11-19 Nov 1793), in James Boswell, Journey of a Tour to the Hebrides (1785)

(Source)

Physics is an organized body of knowledge about nature, and a student of it says that he is learning physics, not nature. Art, like nature, has to be distinguished from the systematic study of it, which is criticism.

Northrop Frye (1912-1991) Canadian literary critic and literary theorist

Anatomy of Criticism, “Polemical Introduction” (1957)

(Source)

Who sneers at epigrams and feigns to scout them,

Believe me, does not know a thing about them.

The real bores are the dreary epic spinners

Who rant of Tereus’ or Thyestes’ dinners,

Who rave of cunning Daedalus applying

The wings to Icarus to teach him flying,

Or else to show what dullards they esteem us

Bleat endless pastorals on Polyphemus.

My unpretentious Muse is not bombastic,

But deems these robes of Tragedy fantastic.

“Such things,” you say, “earn all men’s commendation,

As works of genius and inspiration.”

Ah, very true — those pompous classic leaders

Do get the praise — but then I get the readers![Nescit, crede mihi, quid sint epigrammata, Flacce,

Qui tantum lusus ista iocosque vocat.

Ille magis ludit, qui scribit prandia saevi

Tereos, aut cenam, crude Thyesta, tuam,

Aut puero liquidas aptantem Daedalon alas,

Pascentem Siculas aut Polyphemon ovis.

A nostris procul est omnis vesica libellis,

Musa nec insano syrmate nostra tumet.

“Illa tamen laudant omnes, mirantur, adorant.”

Confiteor: laudant illa, sed ista legunt.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 4, epigram 49 (4.49) (AD 89) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

"To Valerius Flaccus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Flaccus thou knowest not Epigrams,

no more then babes or boyes:

Which deemst them to be nothyng els,

but sports and triflyng toyes:

He rather toyes, and sports it out,

whiche doeth in Verse recite

Fell Tereus dinner, or whiche doeth,

Thyestes supper write:

Or he whiche telles how Dedalus,

did teache his sonne to flie:

Which telleth eke of Plyphem,

the Shepheard with one eye.

From bookes of myne, are quight exempt,

all rancour, rage and gall:

No plaier in his euishe weeds,

heare prankyng see you shall:

Yet these men doe adore (thou sayest)

laude, like and love: in deed,

I graunt you sir those they do laude,

perdie but these thei reed.

[tr. Kendall (1577)]

Thou know'st not, trust me, what are Epigrams,

Flaccus, who think'st them jest and wanton games.

He wantons more, who writes what horrid meat

The plagu'd Tyestes and vex't Tereus eat,

Or Daedalus fitting is boy to fly,

Or Polyphemus' flocks in Sicily.

My booke no windy words nor turgid needes,

Nor swells my Muse with mad Cothurnall weedes.

Yet those things all men praise, admire, adore.

True; they praise those, but read these poems more.

[tr. May (1629)]

Though little know'st what epigram contains,

Who think'st it all a joke in jocund strains.

He direly jokes, who bids a Tereus dine;

Or dresses suppers like, Thyestes, thine;

Feins him who fits the boy with melting wings,

Or the sweet shepherd Polyphemus sings.

Or muse disdains by fustian to excel;

by rant to rattle, or in buskin swell.

Those strains the learn'd applaud, admire, adore.

Those they applaud, I own; but these explore.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), ep. 48]

You little know what Epigram contains,

Who deem it but a jest in jocund strains.

He rather jokes, who writes what horrid meat

The plagued Thyestes and vex't Tereus eat;

Or tells who robed the boy with melting wings;

Or of the shepherd Polyphemus sings.

Our muse disdains by fustian to excel,

By rant to rattle, or in buskins swell.

Though turgid themes all men admire, adore,

Be well assured they read my poems more.

[Westminster Review (Apr 1853)]

He knows not, Flaccus, believe me, what Epigrams really are,

who calls them mere trifles and frivolities.

He is much more frivolous, who writes of the feast of the cruel

Tereus; or the banquet of the unnatural Thyestes;

or of Daedalus fitting melting wings to his son's body;

or of Polyphemus feeding his Sicilian flocks.

From my effusions all tumid ranting is excluded;

nor does my Muse swell with the mad garment of Tragedy.

"But everything written in such a style is praised, admired, and adored by all."

I admit it. Things in that style are praised; but mine are read.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

He does not know, believe me, what epigrams are, Flaccus,

who styles them only frivolities and quips.

He is more frivolous who writes of the meal of savage

Tereus, or of thy banquet, dyspeptic Thyestes,

or of Daedalus fitting to his son melting wings,

or of Polyphemus pasturing Sicilian sheep.

Far from poems of mine is all turgescence,

nor does my Muse swell with frenzied tragic train.

"Yet all men praise those tragedies, admire, worship them."

I grant it: those they praise, but they read the others.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

What makes an epigram he knows not best

Who deems it, Flaccus, but an idle jest.

They rather jest, who Tereus' crime indict

Or the foul banquet of Thyestes write,

Or Icarus equipped with waxen wing

Or Polyphemus and his shepherding.

No fustian ornaments my page abuse

Nor struts in senseless pomp my tragic Muse.

"Men praise," you say, "and call such verse divine."

Yes, they may praise it, but they study mine.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #188, "A Defence of Epigram"]

He does not know what epigrams

Are really meant to be

Who calls them only jests and jokes

Or comic poetry --

A dimwit dilettante's delight,

Mere vers de societé

He really is the one who jests

Who writes about the stew

Served Tereus, or that loathsome meal

Of children served to you,

Thyestes, indigestion-prone,

Of sons your brother slew.

Or Daedalus fitting Icarus

With two liquescent wings,

Or who of Polyphemus tending

Sheep in Sicily sings,

And those huge, monstrous boulders which

He at Ulysses flings.

Far from my verse is any trace

Of rank turgidity.

My Muse has never donned the robes

Of pompous tragedy.

"But that's what's praised!" But what is read?

My earthy poetry!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

To say that epigrams are only jokes and gags

is not to know what they are, my good friend Flaccus.

The poet is more entertaining who asks you to dine

at the cannibal board of Tereus, or describes,

oh indigestible Thyestes, your dinner party;

or the diverting poet turns your attention away

to the mythical sight of Daedalus, fittingly typed

as the one who tailored those tender wings for his son;

or wanders off with Polyphemus, the pastoral giant

pasturing preposterous sheep. Far be it from me

to enlarge on the standard rhetorical situation

and wax eloquent in the interests of inflation.

Our Muse makes no use of the billowing robes

that stalk the figures of Tragedy. "But those poems

are what everyone praises and adores."

I admit it, they praise them, but they read ours.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Who deem epigrams mere trifles,

Flaccus, know not epigram.

He trifles who describes the meal

wild Tereus, rude Thyestes ate,

The Cretan Glider moulting wax,

the one-eyed shepherd herding sheep.

Foreign to my verse the tragic sock,

it's turgid, ranting rhetoric.

"Men praise -- esteem -- revere these works."

True: them they praise ... while reading me.

[tr. Whigham (1987)]

Anybody who calls them just frivolities and jests, Flaccus, doesn't know what epigrams are, believe me. More frivolous is the poet who writes about the meal of savage Tereus or your dinner, dyspeptic Thyestes, or Daedalus fitting his boy with liquid wings, or Polyphemus feeding Sicilian sheep. All bombast is far from my little books, neither does my Muse swell with tragedy's fantastic robe. "And yet all the world praises such things and admires and marvels." I admit it: that they praise, but this they read.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Quite clueless, Flaccus, all these sorry folks

Who brand short poems mere badinage and jokes.

Want to know who's more idle? The big boys,

Our Epic Poets, who rehearse the joys

Of serving human flesh up à la carte --

Tereus' bloody banquet or the huge tart

Chez Thyestes ("It's a little gristly!").

Or they serve us crap, like how remissly

Daedalus made -- with wax, imagine! -- wings

For his poor doomed son. Then Big Epic sings

Of arms and the -- not "man" -- one-eyed giant?

Polyphemus: his brain was far from pliant,

So Homer made him watch sheep in Sicily.

Pardon me for carping so pissily,

Flaccus, at insults to my epigrams,

So far from the bloated whimsy that crams

Our big-assed epics. All men blare in praise

of these "classics," you say, and bask in their rays.

I will not disagree, but mark my word:

Some day, far off, a wise man will be heard

To say, "Classics we all want to have read,

Never to read." My books get read instead!

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

You think my epigrams are silly?

Far worse is bombast uttered shrilly --

Like Tereus baking human pie.

Or Daedal son who tried to fly.

Monster Cyclopes keeping sheep.

My verse is of such nonsense free.

It poses not as tragedy.

But praise for those things does exceed?

Those things men praise -- but mine they read.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

One doesn't fathom epigrams, believe me,

Flaccus, who labels them mere jokes and play.

He's trifling who writes of savage Tereus' mean

or yours, queasy Thyestes, or the way

Daedalus fit his boy with melting wings

or Polyphemus grazed Sicilian flocks.

My little books shun bombast and my Muse

won't rave in puffed-up tragedy's long frocks.

"Yet all admire, praise, honor those," Indeed,

they praise those, I confess, but these they read.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Trust me, Flaccus, anyone who says it's just "ditties" and "jokes"

doesn't know what epigram is.

The real joker is the poet who describes the feast of cruel

Tereus, or the dinner that gave Thyestes indigestion,

or Daedalus strapping melting wings to his son,

or Polyphemus pasturing his Sicilian sheep.

No puffery gets near my little books;

my Muse doesn't swell and strut in the trailing robe of Tragedy.

"But that stuff gets the applause, the awe, the worship."

I can't deny it: that stuff does get the applause. But my stuff gets read.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

The only way to forestall the work of criticism is through censorship, which has the same relation to criticism that lynching has to justice.

Northrop Frye (1912-1991) Canadian literary critic and literary theorist

Anatomy of Criticism, “Polemical Introduction” (1957)

(Source)

A painting in a museum probably hears more foolish remarks than anything else in the world .

[Ce qui entend le plus de bêtises dans le monde est peut-être un tableau de musée.]

The Brothers Goncourt - Edmond (1822-96) & Jules (1830-70), French writers [a.k.a. J.E. de Goncourt]

Idées et sensations (1866)

(Source)

Often mis-cited to just Edmond. Alternate translations:

[Fascism] imagines the masses not as a pluralistic citizenry but as a primal horde whose power can be awakened by playing upon atavistic feelings of hatred and belonging. Its chosen leader must exhibit strength: his refusal to compromise and readiness to attack are seen as signs of tough-mindedness, while any concern for constitutionality or the rule of law are disdained as signs of weakness. The most powerful myth, however, is that of the embattled collective. Critics are branded as traitors, while those who do not fit the criteria for inclusion are vilified as outsiders, terrorists, and criminals.

Peter E, Gordon (b. 1966) American intellectual historian

“Why Historical Analogy Matters,” New York Review of Books (7 Jan 2020)

(Source)

Nobody wants constructive criticism; it’s all we can do to put up with constructive praise.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 4 (1963)

(Source)

Since we all need reproving and rebuking, and since we all know that we need reproving and rebuking, we ought — if we were logical — to be extremely grateful to those who reprove and rebuke us. And I suppose that, sooner or later, we are; but almost invariably later.

People ask you for criticism, but they only want praise.

W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) English novelist and playwright [William Somerset Maugham]

Of Human Bondage, ch. 50 (1915)

(Source)

As President of our country and Commander-in-Chief of our military, I accept that people are going to call me awful things every day, and I will always defend their right to do so.

Barack Obama (b. 1961) American politician, US President (2009-2017)

Speech, United Nations (25 Sep 2012)

(Source)

A society is most vigorous, and appealing, when both partisan and critic are legitimate voices in the permanent dialogue that is the testing of ideas and experience. One can be a critic of one’s country without being an enemy of its promise.

Daniel Bell (1919-2011) American sociologist, writer, editor, academic

The End of Ideology, Introduction (1961 ed.)

(Source)

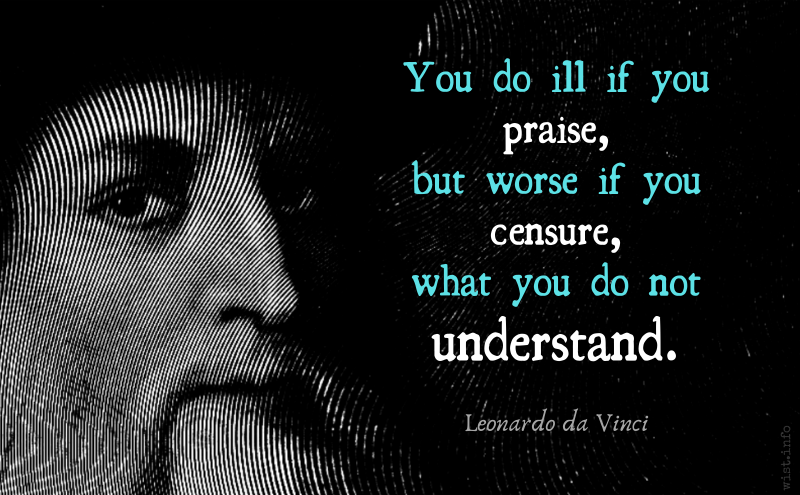

You do ill if you praise, but worse if you censure, what you do not understand.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Italian artist, engineer, scientist, polymath

Notebook entry (c. 1500), Leonardo da Vinci’s Note-Books (1906) [tr. MacCurdy]

(Source)

Codice Atlantico 76 v. a.

It is better to correct your own faults than those of another.

[Κρέσσον τὰ οἰκήϊα ἐλέγχειν ἁμαρτήματα ἢ τὰ ὀθνεῖα.]

Democritus (c. 460 BC - c. 370 BC) Greek philosopher

Frag. 60 (Diels) [tr. Bakewell (1907)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Diels cites this as "Fragment 60, (114 N.) DEMOKRATES. 25"; collected in Joannes Stobaeus (Stobaios) Anthologium III, 13, 46. Bakewell lists this under "The Golden Sayings of Democritus." Freeman notes this as one of the Gnômae, from a collection called "Maxims of Democratês," but because Stobaeus quotes many of these as "Maxims of Democritus," they are generally attributed to the latter.

Alternate translations:

- "It is better to examine one's own faults than those of others." [tr. Freeman (1948)]

- "It is better to examine your own mistakes than those of others." [tr. Barnes (1987)]

- "It is better to rebuke familiar faults than foreign ones." [tr. @sententiq (2018)]

- "Rather examine your own faults than those of others." [Source]

Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye? Or how can you say to your neighbor, “Let me take the speck out of your eye,” while the log is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take the speck out of your neighbor’s eye.

The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Matthew 7:3-5 [NRSV]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- [KJV] "And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother's eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye? Or how wilt thou say to thy brother, Let me pull out the mote out of thine eye; and, behold, a beam is in thine own eye? Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother's eye."

- [GNT] "Why, then, do you look at the speck in your brother's eye and pay no attention to the log in your own eye? How dare you say to your brother, 'Please, let me take that speck out of your eye,' when you have a log in your own eye? You hypocrite! First take the log out of your own eye, and then you will be able to see clearly to take the speck out of your brother's eye.

The Bible has been interpreted to justify such evil practices as, for example, slavery, the slaughter of prisoners of war, the sadistic murders of women believed to be witches, capital punishment for hundreds of offenses, polygamy, and cruelty to animals. It has been used to encourage belief in the grossest superstition and to discourage the free teaching of scientific truths. We must never forget that both good and evil flow from the Bible. It is therefore not above criticism.

Steve Allen (1922-2000) American composer, entertainer, and wit.

More Steve Allen on the Bible, Religion, and Morality, Introduction (1993)

(Source)

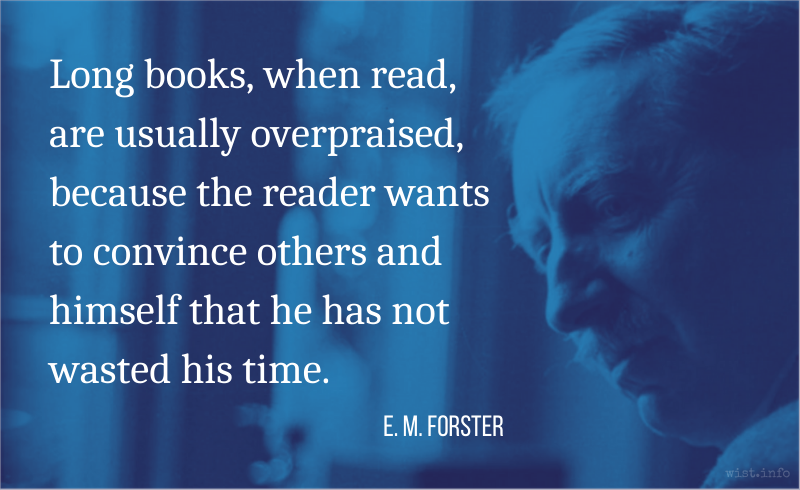

Long books, when read, are usually overpraised, because the reader wants to convince others and himself that he has not wasted his time.

E. M. Forster (1879-1970) English novelist, essayist, critic, librettist [Edward Morgan Forster]

Commonplace Book (1985) [ed. Gardner]

(Source)

He who would acquire fame must not show himself afraid of censure. The dread of censure is the death of genius.

William G. Simms (1806-1870) American writer and politician

Egeria, Or Voices of Thought and Counsel, for the Woods and Wayside, “Ambition” (1853)

(Source)

One mustn’t criticize other people on grounds where he can’t stand perpendicular himself.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, ch. 26 “The First Newspaper” (1889)

(Source)

ANTON EGO: In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little, yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so.

Your minds that once did stand erect and strong,

What madness swerves them from their wonted course?

[Quo vobis mentes, rectae quae stare solebant

antehac, dementis sese flexere viai?]Ennius (239-169 BC) Roman poet, writer [Quintus Ennius]

Annals, Book 6, frag. 11 [tr. Falconer (1923)]

(Source)

Setting the words of Appius Claudius to verse, when Appius in his old age berated the Senate for considering peace and alliance with King Pyrrhus of Epirus, who had defeated them (in a "Pyrhhic victory") at Heraclea (280 BC). Fragment recorded in Cicero, De Senectute, ch. 6 / sec. 16 (4.16) (44 BC).

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Why seid Appius haue ye inclyned and revaled youre couragious hertys whiche til nowe were accustumyd to be ferme and stidfast. Be ye madd or for lak of discressyon agree ye for to condescend and desyre ye to make alliance and peas with kyng Pirrus bycause that he putteth in strength for to putt you downe and in subjection and wolde destroye yowe?

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]

Why do your wits

And senses so rave?

What foolish conceit

Doth encumber your brain?

Where be the ripe judgments,

Which wont you were to have,

To agree to your country's

Ruin most plain?

[tr. Newton (1569)]

Whether now bend your minds, a headlong fall to bring,

Which heretofore had wont to stand, as straight as any thing.

[tr. Austin (1648)]

Whither now do you bend your Thoughts

Which, heretofore, were firm and resolute,

What! madly on your Ruin. ? --

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

What Frenzy now has your wild Minds possest?

You, who were first with sagest Counsels blest,

Your selves on sure Destruction thus to throw!

[tr. Logan (1744)]

Shall folly now that honoured Council sway,

Where sacred wisdom wont to point the way!

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

Ah! wither have your minds demented turned themselves, wich heretofore were wont to stand erect?

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

Whither have your minds, which used to stand upright before, in folly turned away?

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

Wont to stand firm, upon what devious way

Demented rush ye now?

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

Whither have swerved the souls so firm of yore?

Is sense grown senseless? Can feet stand no more?

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

Where are the minds that used to stand serene,

where is the bravery that once has been?

[tr. Allison (1916)]

What is this madness that has turned your minds, until now firm and strong, from their course?

[tr. Grant (1960, 1971 ed.)]

Where are your minds? They always stood up straight till now! Are you mad? Where did you miss the road?

[tr. Copley (1967)]

Up until now your minds were straight and firm.

What bends them now onto this foolish path?

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]

How on earth could your mind

Once upright and dignified

Take a downturn and backslide?

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

What madness has turned your minds, once firm and strong, from their course?

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

Abuse is a proof that you are felt. If they praise you, you will work no revolution.

America is therefore a free country, in which, lest anyone be hurt by your remarks, you are not allowed to speak freely of private individuals or of the State; of the citizen or of the authorities; of public or of private undertakings; or, in short, of anything at all, except it be of the climate and the soil; and even then Americans will be found ready to defend either the one or the other, as if they had been contrived by the inhabitants of the country.

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) French writer, diplomat, politician

Democracy in America, Vol. 1, “Public Spirit in the United States” (1835) [tr. Reeve (1839)]

(Source)

Whether Parliament is either a representative body or an efficient one is questionable, but I value it because it criticizes and talks, and because its chatter gets widely reported. So two cheers for Democracy: one because it admits variety and two because it permits criticism. Two cheers are quite enough: there is no occasion to give three.

E. M. Forster (1879-1970) English novelist, essayist, critic, librettist [Edward Morgan Forster]

“What I Believe,” The Nation (16 Jul 1938)

(Source)

The writer’s role is to menace the public’s conscience. He must have a position, a point of view. He must see the arts as a vehicle of social criticism and he must focus on the issues of his time.

The slander of some people is as great a recommendation as the praise of others. For one is as much hated by the dissolute world, on the score of virtue, as by the good, on that of vice.

Henry Fielding (1707-1754) English novelist, dramatist, satirist

The Temple Beau, Act 1, sc. 1 (1729)

(Source)

A torn jacket is soon mended; but hard words bruise the heart of a child.