There is no heroic poem in the world but is at bottom a biography, the life of a man; also, it may be said, there is no life of a man, faithfully recorded, but is a heroic poem of its sort, rhymed or unrhymed.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

“Sir Walter Scott,” London and Westminster Review No. 12 and 55, Art. 2 (1838-01)

(Source)

A review of Scott's Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Baronet, Vols. 1-6 (1837). Reprinted in Carlyle, Critical and Miscellaneous Essays (1827-1855).

Quotations about:

epic

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

“What do you think is going on, anyway?”

Some horrible Wagnerian thing, I told him, full of blood, thunder, and death for us all.

“Oh, the usual,” Luke said.

Exactly, I replied.

Roger Zelazny (1937-1995) American writer

“Coming to a Cord,” Pirate Writings, #7 [Frakir] (1995)

(Source)

Who sneers at epigrams and feigns to scout them,

Believe me, does not know a thing about them.

The real bores are the dreary epic spinners

Who rant of Tereus’ or Thyestes’ dinners,

Who rave of cunning Daedalus applying

The wings to Icarus to teach him flying,

Or else to show what dullards they esteem us

Bleat endless pastorals on Polyphemus.

My unpretentious Muse is not bombastic,

But deems these robes of Tragedy fantastic.

“Such things,” you say, “earn all men’s commendation,

As works of genius and inspiration.”

Ah, very true — those pompous classic leaders

Do get the praise — but then I get the readers![Nescit, crede mihi, quid sint epigrammata, Flacce,

Qui tantum lusus ista iocosque vocat.

Ille magis ludit, qui scribit prandia saevi

Tereos, aut cenam, crude Thyesta, tuam,

Aut puero liquidas aptantem Daedalon alas,

Pascentem Siculas aut Polyphemon ovis.

A nostris procul est omnis vesica libellis,

Musa nec insano syrmate nostra tumet.

“Illa tamen laudant omnes, mirantur, adorant.”

Confiteor: laudant illa, sed ista legunt.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 4, epigram 49 (4.49) (AD 89) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

"To Valerius Flaccus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Flaccus thou knowest not Epigrams,

no more then babes or boyes:

Which deemst them to be nothyng els,

but sports and triflyng toyes:

He rather toyes, and sports it out,

whiche doeth in Verse recite

Fell Tereus dinner, or whiche doeth,

Thyestes supper write:

Or he whiche telles how Dedalus,

did teache his sonne to flie:

Which telleth eke of Plyphem,

the Shepheard with one eye.

From bookes of myne, are quight exempt,

all rancour, rage and gall:

No plaier in his euishe weeds,

heare prankyng see you shall:

Yet these men doe adore (thou sayest)

laude, like and love: in deed,

I graunt you sir those they do laude,

perdie but these thei reed.

[tr. Kendall (1577)]

Thou know'st not, trust me, what are Epigrams,

Flaccus, who think'st them jest and wanton games.

He wantons more, who writes what horrid meat

The plagu'd Tyestes and vex't Tereus eat,

Or Daedalus fitting is boy to fly,

Or Polyphemus' flocks in Sicily.

My booke no windy words nor turgid needes,

Nor swells my Muse with mad Cothurnall weedes.

Yet those things all men praise, admire, adore.

True; they praise those, but read these poems more.

[tr. May (1629)]

Though little know'st what epigram contains,

Who think'st it all a joke in jocund strains.

He direly jokes, who bids a Tereus dine;

Or dresses suppers like, Thyestes, thine;

Feins him who fits the boy with melting wings,

Or the sweet shepherd Polyphemus sings.

Or muse disdains by fustian to excel;

by rant to rattle, or in buskin swell.

Those strains the learn'd applaud, admire, adore.

Those they applaud, I own; but these explore.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), ep. 48]

You little know what Epigram contains,

Who deem it but a jest in jocund strains.

He rather jokes, who writes what horrid meat

The plagued Thyestes and vex't Tereus eat;

Or tells who robed the boy with melting wings;

Or of the shepherd Polyphemus sings.

Our muse disdains by fustian to excel,

By rant to rattle, or in buskins swell.

Though turgid themes all men admire, adore,

Be well assured they read my poems more.

[Westminster Review (Apr 1853)]

He knows not, Flaccus, believe me, what Epigrams really are,

who calls them mere trifles and frivolities.

He is much more frivolous, who writes of the feast of the cruel

Tereus; or the banquet of the unnatural Thyestes;

or of Daedalus fitting melting wings to his son's body;

or of Polyphemus feeding his Sicilian flocks.

From my effusions all tumid ranting is excluded;

nor does my Muse swell with the mad garment of Tragedy.

"But everything written in such a style is praised, admired, and adored by all."

I admit it. Things in that style are praised; but mine are read.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

He does not know, believe me, what epigrams are, Flaccus,

who styles them only frivolities and quips.

He is more frivolous who writes of the meal of savage

Tereus, or of thy banquet, dyspeptic Thyestes,

or of Daedalus fitting to his son melting wings,

or of Polyphemus pasturing Sicilian sheep.

Far from poems of mine is all turgescence,

nor does my Muse swell with frenzied tragic train.

"Yet all men praise those tragedies, admire, worship them."

I grant it: those they praise, but they read the others.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

What makes an epigram he knows not best

Who deems it, Flaccus, but an idle jest.

They rather jest, who Tereus' crime indict

Or the foul banquet of Thyestes write,

Or Icarus equipped with waxen wing

Or Polyphemus and his shepherding.

No fustian ornaments my page abuse

Nor struts in senseless pomp my tragic Muse.

"Men praise," you say, "and call such verse divine."

Yes, they may praise it, but they study mine.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #188, "A Defence of Epigram"]

He does not know what epigrams

Are really meant to be

Who calls them only jests and jokes

Or comic poetry --

A dimwit dilettante's delight,

Mere vers de societé

He really is the one who jests

Who writes about the stew

Served Tereus, or that loathsome meal

Of children served to you,

Thyestes, indigestion-prone,

Of sons your brother slew.

Or Daedalus fitting Icarus

With two liquescent wings,

Or who of Polyphemus tending

Sheep in Sicily sings,

And those huge, monstrous boulders which

He at Ulysses flings.

Far from my verse is any trace

Of rank turgidity.

My Muse has never donned the robes

Of pompous tragedy.

"But that's what's praised!" But what is read?

My earthy poetry!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

To say that epigrams are only jokes and gags

is not to know what they are, my good friend Flaccus.

The poet is more entertaining who asks you to dine

at the cannibal board of Tereus, or describes,

oh indigestible Thyestes, your dinner party;

or the diverting poet turns your attention away

to the mythical sight of Daedalus, fittingly typed

as the one who tailored those tender wings for his son;

or wanders off with Polyphemus, the pastoral giant

pasturing preposterous sheep. Far be it from me

to enlarge on the standard rhetorical situation

and wax eloquent in the interests of inflation.

Our Muse makes no use of the billowing robes

that stalk the figures of Tragedy. "But those poems

are what everyone praises and adores."

I admit it, they praise them, but they read ours.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Who deem epigrams mere trifles,

Flaccus, know not epigram.

He trifles who describes the meal

wild Tereus, rude Thyestes ate,

The Cretan Glider moulting wax,

the one-eyed shepherd herding sheep.

Foreign to my verse the tragic sock,

it's turgid, ranting rhetoric.

"Men praise -- esteem -- revere these works."

True: them they praise ... while reading me.

[tr. Whigham (1987)]

Anybody who calls them just frivolities and jests, Flaccus, doesn't know what epigrams are, believe me. More frivolous is the poet who writes about the meal of savage Tereus or your dinner, dyspeptic Thyestes, or Daedalus fitting his boy with liquid wings, or Polyphemus feeding Sicilian sheep. All bombast is far from my little books, neither does my Muse swell with tragedy's fantastic robe. "And yet all the world praises such things and admires and marvels." I admit it: that they praise, but this they read.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Quite clueless, Flaccus, all these sorry folks

Who brand short poems mere badinage and jokes.

Want to know who's more idle? The big boys,

Our Epic Poets, who rehearse the joys

Of serving human flesh up à la carte --

Tereus' bloody banquet or the huge tart

Chez Thyestes ("It's a little gristly!").

Or they serve us crap, like how remissly

Daedalus made -- with wax, imagine! -- wings

For his poor doomed son. Then Big Epic sings

Of arms and the -- not "man" -- one-eyed giant?

Polyphemus: his brain was far from pliant,

So Homer made him watch sheep in Sicily.

Pardon me for carping so pissily,

Flaccus, at insults to my epigrams,

So far from the bloated whimsy that crams

Our big-assed epics. All men blare in praise

of these "classics," you say, and bask in their rays.

I will not disagree, but mark my word:

Some day, far off, a wise man will be heard

To say, "Classics we all want to have read,

Never to read." My books get read instead!

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

You think my epigrams are silly?

Far worse is bombast uttered shrilly --

Like Tereus baking human pie.

Or Daedal son who tried to fly.

Monster Cyclopes keeping sheep.

My verse is of such nonsense free.

It poses not as tragedy.

But praise for those things does exceed?

Those things men praise -- but mine they read.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

One doesn't fathom epigrams, believe me,

Flaccus, who labels them mere jokes and play.

He's trifling who writes of savage Tereus' mean

or yours, queasy Thyestes, or the way

Daedalus fit his boy with melting wings

or Polyphemus grazed Sicilian flocks.

My little books shun bombast and my Muse

won't rave in puffed-up tragedy's long frocks.

"Yet all admire, praise, honor those," Indeed,

they praise those, I confess, but these they read.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Trust me, Flaccus, anyone who says it's just "ditties" and "jokes"

doesn't know what epigram is.

The real joker is the poet who describes the feast of cruel

Tereus, or the dinner that gave Thyestes indigestion,

or Daedalus strapping melting wings to his son,

or Polyphemus pasturing his Sicilian sheep.

No puffery gets near my little books;

my Muse doesn't swell and strut in the trailing robe of Tragedy.

"But that stuff gets the applause, the awe, the worship."

I can't deny it: that stuff does get the applause. But my stuff gets read.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns …

driven time and again off course, once he had plundered

the hallowed heights of Troy.

Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds,

many pains he suffered, heartsick on the open sea,

fighting to save his life and bring his comrades home.[Ἄνδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ

πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσε·

πολλῶν δ’ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω,

πολλὰ δ’ ὅ γ’ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν ἄλγεα ὃν κατὰ θυμόν,

ἀρνύμενος ἥν τε ψυχὴν καὶ νόστον ἑταίρων.]Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Odyssey [Ὀδύσσεια], Book 1, l. 1ff (1.1-5) (c. 700 BC) [tr. Fagles (1996)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

The man, O Muse, inform, that many a way

Wound with his wisdom to his wished stay;

That wander’d wondrous far, when he the town

Of sacred Troy had sack’d and shiver’d down;

The cities of a world of nations,

With all their manners, minds, and fashions,

He saw and knew; at sea felt many woes,

Much care sustain’d, to save from overthrows

Himself and friends in their retreat for home;

But so their fates he could not overcome.

[tr. Chapman (1616)]

Tell me, O Muse, th’ adventures of the man

That having sack’d the sacred town of Troy,

Wander’d so long at sea; what course he ran

By winds and tempests driven from his way:

That saw the cities, and the fashions knew

Of many men, but suffer’d grievous pain

To save his own life, and bring home his crew.

[tr. Hobbes (1675)]

The man for wisdom's various arts renown'd,

Long exercised in woes, O Muse! resound;

Who, when his arms had wrought the destined fall

Of sacred Troy, and razed her heaven-built wall,

Wandering from clime to clime, observant stray'd,

Their manners noted, and their states survey'd,

On stormy seas unnumber'd toils he bore,

Safe with his friends to gain his natal shore.

[tr. Pope (1725)]

Muse make the man thy theme, for shrewdness famed

And genius versatile, who far and wide

A Wand’rer, after Ilium overthrown,

Discover’d various cities, and the mind

And manners learn’d of men, in lands remote.

He num’rous woes on Ocean toss’d, endured,

Anxious to save himself, and to conduct

His followers to their home.

[tr. Cowper (1792)]

Sing me, O Muse, that hero wandering

Who of men's minds did much experience reap,

And knew the citied realms of many a king,

Even from the hour he smote the Trojan keep.

Also a weight of sorrows in the deep

Brooding he bore, in earnest hope to save,

'Mid hard emprise and labour all too steep,

Himself and comrades from a watery grave --

Whom yet he rescued not with zeal nor yearnings brave.

[tr. Worsley (1861), st. 1]

Tell me, O Muse, declare to me that man

Tost too and fro by fate, who, when his arms

Had laid Troy's holy city in the dust,

Far wand'ring roam'd on many a tribe of men

To bend his gaze, their minds and thoughts to learn.

Grief upon grief encounter'd he, when, borne

On ocean-waves, his life he carried off

A prize from perils rescued, and would fain

Have homeward led his brethren in arms.

[tr. Musgrave (1869)]

Tell me, oh Muse, of the many-sided man,

Who wandered far and wide full sore bestead,

When had razed the mighty town of Troy:

And of many a race of human-kind he saw

The cities; and he learned their mind and ways:

And on the deep fully many a woe he bore

In his own bosom, while he strove to save

His proper life, and his comrades' home-return.

[tr. Bigge-Wither (1869)]

Tell me, Muse, of that man, so ready at need, who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy, and many were the men whose towns he saw and whose mind he learnt, yea, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep, striving to win his own life and the return of his company. Nay, but even so he saved not his company, though he desired it sore.

[tr. Butcher/Lang (1879)]

Tell me, O Muse, of the Shifty, the man who wandered afar,

After the Holy burg, Troy-town, he had wasted with war:

He saw the towns of menfolk, and the mind of men did he learn;

As he warded his life in the world, and his fellow-farers' return,

Many a grief of heart on the deep-sea flood he bore,

Nor yet might he save his fellows, for all that he longed for it sore.

[tr. Morris (1887)]

Speak to me, Muse, of the adventurous man who wandered long after he sacked the sacred citadel of Troy. Many the men whose towns he saw, whose ways he proved; and many a pang he bore in his breast at sea while struggling for his life and his men's safe return.

[tr. Palmer (1891)]

Tell me, oh Muse, of that ingenious hero who travelled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy. Many cities did he visit, and many were the nations with whose manners and customs he was acquainted; moreover he suffered much by sea while trying to save his own life and bring his men safely home.

[tr. Butler (1898)]

Tell me, O Muse, of that many-sided hero who traveled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy. Many cities did he visit, and many were the people with whose customs and thinking he was acquainted; many things he suffered at sea while seeking to save his own life and to achieve the safe homecoming of his companions.

[tr. Butler (1898), rev. Power/Nagy]

That man, tell me O Muse the song of that man, that versatile man, who in very many ways veered from his path and wandered off far and wide, after he had destroyed the sacred citadel of Troy. Many different cities of many different people did he see, getting to know different ways of thinking. Many were the pains he suffered in his heart while crossing the sea struggling to merit the saving of his own life and his own homecoming as well as the homecoming of his comrades.

[tr. Butler (1898), rev. Kim/McCray/Nagy/Power (2018)]

Tell me, O Muse, of the man of many devices, who wandered full many ways after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy. Many were the men whose cities he saw and whose mind he learned, aye, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the sea, seeking to win his own life and the return of his comrades.

[tr. Murray (1919)]

O Divine Poesy,

Goddess-daughter of Zeus,

Sustain for me

This song of the various-minded man,

Who after he had plundered

The innermost citadel of hallowed Troy

Was made to stray grievously

About the coasts of men,

The sport of their customs good or bad,

While his heart

Through all the seafaring

Ached in an agony to redeem himself

And bring his company safe home.

[tr. Lawrence (1932)]

Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story

of that man skilled in all ways of contending,

the wandering, harried for years on end after he plundered the stronghold

on the proud height of Troy.

He saw the townlands

and learned the minds of many distant men,

and weathered many bitter nights and days

in his deep heart at sea, while he fought only

to save his life, to bring his shipmates home.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1961)]

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways, who was driven

far journeys after he had sacked Troy's sacred citadel.

Many were they whose cities he saw, whose minds he learned of,

many the pains he suffered in his spirit on the wide sea,

struggling for his own life and the homecoming of his companions.

[tr. Lattimore (1965)]

Muse, tell me of the man of many wiles,

the man who wandered many paths of exile

after he sacked Troy's sacred citadel.

He saw the cities -- mapped the minds -- of many;

and on the sea, his spirit suffered every

adversity -- to keep his life intact;

to bring his comrades back.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1990)]

Speak, Memory -- Of the cunning hero,

The wanderer, blown off course time and again

After he plundered Troy's sacred heights. Speak

Of all the cities he saw , the minds he grasped,

The suffering deep in his heart at sea

As he struggled to survive and bring his men home.

[tr. Lombardo (2000)]

Tell me, Muse, of the man versatile and resourceful, who wandered many a sea-mile afer he ransacked Troy's holy city. Many the men whose towns he observed, whose minds he discovered, many the pains in his heart he suffered, traversing the seaway, fighting for his own life and a way back home for his comrades.

[tr. Merrill (2002)]

Tell me, Muse, the story of that resourceful man who was driven to wander far and wide after he had sacked the holy citadel of Troy. He saw the cities of many people and he learnt their ways. He suffered great anguish on the high seas in his struggles to preserve his life and bring his comrades home.

[tr. DCH Rieu (2002)]

Tell me, Muse, of the man of many turns, who was driven

far and wide after he had sacked the sacred city of Troy.

Many were the men whose cities he saw, and learnt their minds,

many the sufferings on the open sea he endured in his heart,

struggling for his own life and his companions' homecoming.

[tr. Verity (2016)]

Tell me about a complicated man.

Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost

when he had wrecked the holy town of Troy,

and where he went, and who he met, the pain

he suffered in the storms at sea, and how

he worked to save his life and bring his men

back home.

[tr. Wilson (2017)]

The man, Muse -- tell me about that resourceful man, who wandered

far and wide, when he'd sacked Troy's sacred citadel:

many men's townships he saw, and learned their ways of thinking,

many the griefs he suffered at heart on the open sea,

battling for his own life and his comrades' homecoming.

[tr. Green (2018)]

Muse, speak to me now of that resourceful man

who wandered far and wide after ravaging

the sacred citadel of Troy. He came to see

many people’s cities, where he learned their customs,

while on the sea his spirit suffered many torments,

as he fought to save his life and lead his comrades home.

[tr. Johnston (2019)]

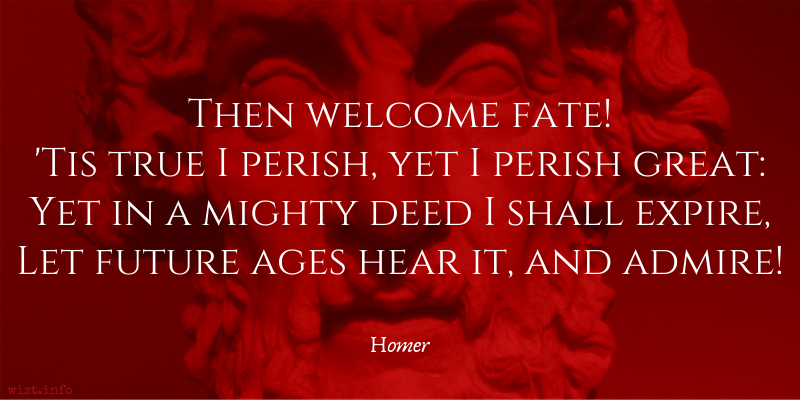

Then welcome fate!

‘Tis true I perish, yet I perish great:

Yet in a mighty deed I shall expire,

Let future ages hear it, and admire![νῦν αὖτέ με μοῖρα κιχάνει.

μὴ μὰν ἀσπουδί γε καὶ ἀκλειῶς ἀπολοίμην,

ἀλλὰ μέγα ῥέξας τι καὶ ἐσσομένοισι πυθέσθαι.]Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Iliad [Ἰλιάς], Book 22, l. 303ff (22.303) [Hector] (c. 750 BC) [tr. Pope (1715-20), l. 385ff]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

But Fate now conquers; I am hers; and yet not she shall share

In my renown; that life is left to every noble spirit,

And that some great deed shall beget that all lives shall inherit.

[tr. Chapman (1611), l. 266ff]

But I will not fall

Inglorious; I will act some great exploit

That shall be celebrated ages hence.

[tr. Cowper (1791), l. 347ff]

Fate overtakes me. Nevertheless I will not perish cowardly and ingloriously at least, but having done some great deed to be heard of even by posterity.

[tr. Buckley (1860)]

My fate hath found me now.

Yet not without a struggle let me die,

Nor all inglorious; but let some great act,

Which future days may hear of, mark my fall.

[tr. Derby (1864)]

Now my fate hath found me. At least let me not die without a struggle or ingloriously, but in some great deed of arms whereof men yet to be born shall hear.

[tr. Leaf/Lang/Myers (1891)]

My doom has come upon me; let me not then die ingloriously and without a struggle, but let me first do some great thing that shall be told among men hereafter.

[tr. Butler (1898)]

Now again is my doom come upon me. Nay, but not without a struggle let me die, neither ingloriously, but in the working of some great deed for the hearing of men that are yet to be.

[tr. Murray (1924)]

But now my death is upon me. Let me at least not die without a struggle, inglorious, but do some big thing first, that men to come shall know of it.

[tr. Lattimore (1951)]

Now the appointed time's upon me. Still, I would not die without delivering a stroke, or die ingloriously, but in some action memorable to men in days to come.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1974)]

So now I meet my doom. Well let me die --

but not without struggle, not without glory, no,

in some great clash of arms that even men to come

will hear of down the years!

[tr. Fagles (1990), l. 359ff]

But now has my doom overcome me. But let me at least not die without making a fight, without glory, but a great deed having done for the men of the future to hear of.

[tr. Merrill (2007)]

May I not die without a fight and without glory

but after doing something big for men to come to learn about.

[tr. @Sentantiq (2011)]

I sing of warfare and a man at war.

From the sea-coast of Troy in early days

He came to Italy by destiny,

To our Lavinian western shore,

A fugitive, this captain, buffeted

Cruelly on land as on the sea

By blows from powers of the air — behind them

Baleful Juno in her sleepless rage.

And cruel losses were his lot in war,

Till he could found a city and bring home

His gods to Latium, land of the Latin race,

The Alban lords, and the high walls of Rome.[Arma virumque canō, Trōiae quī prīmus ab ōrīs

Ītaliam, fātō profugus, Lāvīniaque vēnit

lītora, multum ille et terrīs iactātus et altō

vī superum saevae memorem Iūnōnis ob īram;

multa quoque et bellō passus, dum conderet urbem,

inferretque deōs Latiō, genus unde Latīnum,

Albānīque patrēs, atque altae moenia Rōmae.]Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

The Aeneid [Ænē̆is], Book 1, l. 1ff (1.1-7) (29-19 BC) [tr. Fitzgerald (1981)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Arms and the man I sing who first did come,

Driven by fate, from Troy to Latium.

And Tyrrhen shores; Much toff'd by Land and Sea

By wrath of Gods, and lasting enmity

Of cruell Juno, suffering much by Wars

Whiles he a Citie builds, and Gods transfers

To Latium whence, Latine Originalls

The Alban fathers, and Romes lofty walls.

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]

Arms, and the man I sing, who, forc'd by fate,

And haughty Juno's unrelenting hate,

Expell'd and exil'd, left the Trojan shore.

Long labours, both by sea and land, he bore,

And in the doubtful war, before he won

The Latian realm, and built the destin'd town;

His banish'd gods restor'd to rites divine,

And settled sure succession in his line,

From whence the race of Alban fathers come,

And the long glories of majestic Rome.

[tr. Dryden (1697)]

Arms I sing, and the hero, who first, exiled by fate, came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and by the Lavinian shore: much was he tossed both on sea and land, by the power of those above, on account of the unrelenting rage of cruel Juno: much too he suffered in war till he founded a city, and brought his gods into LatiumL from whence the Latin progeny, the Alban fathers, and the walls of lofty Rome.

[tr. Davidson/Buckley (1854)]

Arms and the man I sing, who first,

By Fate of Ilian realm amerced,

To fair Italia onward bore,

And landed on Lavinium’s shore: --

Long tossing earth and ocean o’er,

By violence of heaven, to sate

Fell Juno’s unforgetting hate:

Much laboured too in battle-field,

Striving his city’s walls to build,

And give his Gods a home:

Thence come the hardy Latin brood,

The ancient sires of Alba’s blood,

And lofty-rampired Rome.

[tr. Conington (1866)]

I sing of arms, and of the man who first

Came from the coasts of Troy to Italy

And the Lavinian shores, exiled by fate.

Much was he tossed about upon the lands

And on the ocean by supernal powers,

Because of cruel Juno's sleepless wrath.

Many things also suffered he in war,

Until he built a city, and his gods

Brought into Latium, whence the Latin race,

The Alban sires, and walls of lofty Rome.

[tr. Cranch (1872)]

I sing of arms and the man who of old from the coasts of Troy came, an exile of fate, to Italy and the shore of Lavinium; hard driven on land and on the deep by the violence of heaven, for cruel Juno's unforgetful anger, and hard bestead in war also, ere he might found a city and carry his gods into Latium; from whom is the Latin race, the lords of Alba, and the stately city Rome.

[tr. Mackail (1885)]

I sing of arms, I sing of him, who from the Trojan land

Thrust forth by Fate, to Italy and that Lavinian strand

First came: all tost about was he on earth and on the deep

By heavenly might for Juno's wrath, that had no mind to sleep:

And plenteous war he underwent ere he his town might frame

And set his Gods in Latian earth, whence is the Latin name,

And father-folk of Alba-town, and walls of mighty Rome.

[tr. Morris (1900)]

Of arms I sing, and of the man, whom Fate

First drove from Troy to the Lavinian shore.

Full many an evil, through the mindful hate

Of cruel Juno, from the gods he bore,

Much tost on earth and ocean, yea, and more

In war enduring, ere he built a home,

And his loved household-deities brought o'er

To Latium, whence the Latin people come,

Whence rose the Alban sires, and walls of lofty Rome.

[tr. Taylor (1907), st. 1]

Arms and the man I sing, who first made way,

predestined exile, from the Trojan shore

to Italy, the blest Lavinian strand.

Smitten of storms he was on land and sea

by violence of Heaven, to satisfy

stern Juno's sleepless wrath; and much in war

he suffered, seeking at the last to found

the city, and bring o'er his fathers' gods

to safe abode in Latium; whence arose

the Latin race, old Alba's reverend lords,

and from her hills wide-walled, imperial Rome.

[tr. Williams (1910)]

Arms I sing and the man who first from the coasts of Troy, exiled by fate, came to Italy and Lavinian shores; much buffeted on sea and land by violence from above, through cruel Juno's unforgiving wrath, and much enduring in war also, till he should build a city and bring his gods ot Latium; whence came the Latin race, the lords of Alba, and the walls of lofty Rome.

[tr. Fairclough (1916)]

Arms and the man I sing, the first who came,

Compelled by fate, an exile out of Troy,

To Italy and the Lavinian coast,

Much buffeted on land and on the deep

By violence of the gods, through that long rage,

That lasting hate, of Juno’s. And he suffered

Much, also, in war, till he should build his town

And bring his gods to Latium, whence, in time,

The Latin race, the Alban fathers, rose

And the great walls of everlasting Rome.

[tr. Humphries (1951)]

I tell about war and the hero who first from Troy's frontier,

Displaced by destiny, came to the Lavinian shores,

To Italy -- a man much travailed on sea and land

By the powers above, because of the brooding anger of Juno,

Suffering much in war until he could found a city

And march his gods into Latium, whence rose the Latin race,

The royal line of Alba and the high walls of Rome.

[tr. Day Lewis (1952)]

I sing of arms and of a man: his fate

had made him fugitive; he was the first

to journey from the coasts of Troy as far

as Italy and the Lavinian shores.

Across the lands and waters he was battered

beneath the violence of High Ones, for

the savage Juno's unforgetting anger;

and many sufferings were his in war

until he brought a city into being

and carried in his gods to Latium;

from this have come the Latin race, the lords

of Alba, and the ramparts of high Rome.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1971)]

I sing of arms and of the man, fated to be an exile, who long since left the land of Troy and came to Italy to the shores of Lavinium; and a great pounding he took by land and sea at the hands of the heavenly gods because of the fierce and unforgetting anger of Juno. Great too were his suffering in war before he could found his city and carry his gods into Latium. this was the beginning of the Latin race, the Alban fathers and the high walls of Rome.

[tr. West (1990)]

I sing of arms and the man, he who, exiled by fate,

first came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and to

Lavinian shores – hurled about endlessly by land and sea,

by the will of the gods, by cruel Juno’s remorseless anger,

long suffering also in war, until he founded a city

and brought his gods to Latium: from that the Latin people

came, the lords of Alba Longa, the walls of noble Rome.

[tr. Kline (2002)]

Arms I sing -- and a man,

The first to come from the shores

Of Troy, exiled by Fate, to Italy

And the Lavinian coast; a man battered

On land and sea by the powers above

In the face of Juno's relentless wrath;

A man who also suffered greatly in war

Until he could found his city and bring his gods

Into Latium, from which arose

The Latin people, our Alban forefathers,

And the high walls of everlasting Rome.

[tr. Lombardo (2005)]

Wars and a man I sing -- an exile driven on by Fate,

he was the first to flee the coast of Troy,

destined to reach Lavinian shores and Italian soil,

yet many blows he took on land and sea from the gods above --

thanks to cruel Juno’s relentless rage -- and many losses

he bore in battle too, before he could found a city,

bring his gods to Latium, source of the Latin race,

the Alban lords and the high walls of Rome.

[tr. Fagles (2006)]

My song is of war and a man: a refugee by fate,

the first from Troy to Italy's Lavinian shores,

battered much on land and sea by blows from gods

obliging brutal Juno's unforgetting rage;

he suffered much in war as well, all to plant

his town and gods in Latium. From here would rise

the Latin race, the Alban lords, and Rome's high walls.

[tr. Bartsch (2021)]

Far over the misty mountains cold

To dungeons deep and caverns old

We must away ere break of day

To seek the pale enchanted gold.The dwarves of yore made mighty spells,

While hammers fell like ringing bells

In places deep, where dark things sleep,

In hollow halls beneath the fells.For ancient king and elvish lord

There many a gleaming golden hoard

They shaped and wrought, and light they caught

To hide in gems on hilt of sword.On silver necklaces they strung

The flowering stars, on crowns they hung

The dragon-fire, in twisted wire

They meshed the light of moon and sun.Far over the misty mountains cold

To dungeons deep and caverns old

We must away, ere break of day,

To claim our long-forgotten gold.Goblets they carved there for themselves

And harps of gold; where no man delves

There lay they long, and many a song

Was sung unheard by men or elves.The pines were roaring on the height,

The winds were moaning in the night.

The fire was red, it flaming spread;

The trees like torches blazed with light.The bells were ringing in the dale

And men they looked up with faces pale;

The dragon’s ire more fierce than fire

Laid low their towers and houses frail.The mountain smoked beneath the moon;

The dwarves they heard the tramp of doom.

They fled their hall to dying fall

Beneath his feet, beneath the moon.Far over the misty mountains grim

To dungeons deep and caverns dim

We must away, ere break of day,

To win our harps and gold from him!J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) English writer, fabulist, philologist, academic [John Ronald Reuel Tolkien]

The Hobbit, ch. 1 “An Unexpected Party” [Thorin, et al.] (1937)

(Source)

Song sung by Thorin Oakenshield and the rest of his dwarvish company.