Strict censure may this harmless sport endure:

My page is wanton, but my life is pure.[Innocuos censura potest permittere lusus:

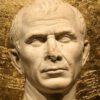

Lasciva est nobis pagina, vita proba.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 4 (1.4.7-8) (AD 85-86) [tr. Duff (1929)]

(Source)

An appeal to Emperor Domitian, who became censor-for-life in AD 85.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Wantons we are; and though our words be such,

Our Lives do differ from our Lines by much.

[tr. Herrick (1648)]

The Censor does with harmless Pastime bear;

My Leaves are wanton, but my Life’s severe.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

The censorship may tolerate innocent jokes:

my page indulges in freedoms, but my life is pure.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Licentious though my page, my life is pure.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

A censor can permit harmless trifling:

wanton is my page; my life is good.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

From censure may my harmless mirth be free,

My page is wanton but my life is clean.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Your censure well such license may endure;

My page is wanton, but my life is pure.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924)]

The censor passes the risqué parts in a play

and my pages can be very gay

without my being that way.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Harmless wit

You may, as Censor, reasonably permit:

My life is strict, however lax my page.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

A censor can permit harmless jollity. My page is wanton, but my life is virtuous.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

A censor can relax, wink just one eye:

My poetry is filthy -- but not I.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

As Censor, you can exercise discretion: my jokes hurt no one; let them be. My page may be dirty, but my life is clean.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

Let not these harmless sports your censure taste:

My lines are wanton, but my life is chaste.

[tr. 17th C Manuscript]

These games are harmless, censor: let them pass.

My poems play around; but not my life.

[tr. Elliot]

Quotations by:

Martial

‘Tis not, believe me, a wise man’s part to say, “I will live.” Tomorrow’s life is too late: live today.

[Non est, crede mihi, sapientis dicere “Vivam”:

Sera nimis vita est crastina: vive hodie.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 15 (1.15.11-12) (AD 85-86) [tr. Bohn’s (1859)]

(Source)

A sentiment echoed in 5.58. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Trust me, it is not wise to say,

I'll live; 'twill be too late tomorrow,

Live if thou'rt wise today.

[tr. Oldmixon (1728)]

"I'll live tomorrow," will a wise man say?

Tomorrow is too late, then live today.

[tr. Hay (1755), quoted in Bohn's, but not in Hay's own book]

Tomorrow I shall live, the fool will say. [...]

Wouldst thou be sure of living? Live today.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 2, ep. 45]

No wisdom 'tis to say "I'll soon begin to live."

'Tis late to live tomorrow; live today.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

It sorts not, believe me, with wisdom to say "I shall live."

Too late is tomorrow's life; live thou today.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

"I'll live tomorrow," no wise man will say;

Tomorrow is too late. Then live today.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #10]

To say, "I mean to live," is folly's place:

Tomorrow's life comes late; live, then, today.

[tr. Duff (1929)]

It's not a wise man's part to say

"I'll live," Tomorrow's life is much to late.

Live! Today.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Believe me, the wise man does not say "1 shall live." Tomorrow's life is too late. Live today.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

No sage will e'er "I'll live tomorrow" say:

Tomorrow is too late: live thou today.

[tr. WSB]

Good work you’ll find, some poor, and much that’s worse,

It takes all sorts to make a book of verse.[Sunt bona, sunt quaedam mediocria, sunt mala plura

quae legis hic: aliter non fit, Avite, liber.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 16 (1.16) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

"To Avitus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Some things are good, indifferent some, some naught,

You read: a book can't otherwise be wrote.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Here's some good things, some middling, more bad, you will see:

Else a book, my Avitus, it never could be.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 12.6]

Some of my epigrams are good, some moderately so, more bad: there is no other way, Avitus, of making a book.

[tr. Amos (1858), 2.23 (cited as 1.17)]

Of the epigrams which you read here, some are good, some middling, many bad: a book, Avitus, cannot be made in any other way.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Here you will read some few good things, while some

Are mediocre, most are bad: 'tis thus

That every book's compiled.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

There are good things, there are some indifferent, there are more things bad that you read here. Not otherwise, Avitus, is a book produced.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Good work you’ll find, some poor, and much that’s worse;

It takes all sorts to make a book of verse.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Some things are good, some fair, but more you'll say

Are bad herein -- all books are made that way!

[tr. Duff (1929)]

Some of these epigrams are good,

Some mediocre, many bad.

Otherwise, it is understood,

A bookful of poems cannot be had.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Among these lines you'll find a few

that are rather good, more that are only fair,

and a lot that are bad.

From that, Avitus, it may be deduced

just how a book is produced.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Some good, some middling, and some bad

You’ll find here. They are what I had.

[tr. Cunningham (1971)]

Some lines in here are good, some fair,

And most are frankly rotten;

No other kind of book, Avitus,

Can ever be begotten.

[tr. Wender (1980)]

There are good things that you read here, and some indifferent, and more bad. Not otherwise, Avitus, is a book made.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Some good things here, and some not worth a look.

For this is that anomaly, a book.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Some of my poems are good, some

not up to scratch, some

bad.

That’s how it is with most books,

if the truth were told.

Who tells the truth about truth, my dear?

Make way for the judge and the jester.

[tr. Kennelly (2008), "How It Is"]

You'll read some good things here, some fair, more worse.

There's no way else to make a book of verse.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You're reading good poems here, Avitus -- and a few that are so-so, and a lot that are bad; a book doesn't happen any other way.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

Some good, some so-so, most of them naught!

Well, if not worse, the book may still be bought.

[Anon.]

Why fight off fame now beating at your door?

What other writers dare to promise more?

You must make immortality start now,

Not make it wait to give your corpse a bow.[Ante fores stantem dubitas admittere Famam

Teque piget curae praemia ferre tuae?

Post te victurae per te quoque vivere chartae

Incipiant: cineri gloria sera venit.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 25 (1.25.5-8) (AD 85-86) [tr. Wills (2007)]

(Source)

"To Faustinus." (Source (Latin)). Some early writers number this as ep. 26, as noted. Alternate translations:

Wilt not admit fame standing at thy doore?

And take the fruit of all thy paines before?

Fame to the Urne comes late; let those Books live

With thee, which after life to thee must give.

[tr. May (1629), 1.26]

Dost doubt t'admit Fame standing at thy gate?

Thy labour's just reward to bear, dost hate?

That which will after, in thy time let live:

Too late men praise unto our ashes give.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Fame at your portal waits; the door why barr'd?

Why loth to take your labour's just reward?

Let works live with you, which will long survive;

For honours after death too late arrive.

[tr. Hay (1755), 1.26]

Admit fair fame, who dances at thy door;

And dain to reap thyself thy toil's reward.

The strains that shall survive thee, give to soar;

Nor to thine ashes leave the late record.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 2.34]

Do you hesitate to let in Fame when standing for admittance before your threshold, and does it grieve you to reap the rewards of your own diligence? May your poems, which will survive you, begin to live by your means. The glory which is shed upon ashes arrives full late.

[tr. Amos (1858), 1.26 "Posthumous Works"]

Do you hesitate to admit Fame, who is standing before your door; and does it displease you to receive the reward of your labour? Let the writings, destined to live after you, begin to live through your means. Glory comes too late, when paid only to our ashes.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

If after thee thy verses are to live,

Let them begin whilst thou'rt alive. Too late

The glory that illumines but they tomb.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Do you hesitate to admit Fame that stands before your doors, and shrink from winning the reward of your care? Let writings that will live after you by your adi also begin to live now; to the ashes of the dead glory comes too late.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Nay, doth it irk you that reward is nigh?

Why bar out fame who standeth at the gate?

Give birth to what must live, before you die,

For honour paid to ashes comes too late.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Fame stands before your threshold, let her in;

Are you ashamed your meed of praise to win?

Your books will long outlive you in their fame;

Come then, begin, for ashes have no name.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #14]

Tell me why you hesitate;

Fame is standing at your door.

Take the prize she long has offered,

Long has held for you in store!

Let works that will survive you after

You have trod the path so dread

Live now, while you still are living.

Fame comes too late to the dead.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Fame is at the door,

and you keep her waiting.

You can't bring yourself to accept

the reward of your worry?

Hurry!

Let those pages begin to live -- show your face.

They will live on after you're gone in any case.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Do you hesitate to let Fame in when she stands at your door? Are you reluctant to take the reward for your pains? Your pages will live after you; let them also begin to live through you. Glory comes late to the grave.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Amos (above) provides a number of examples where the last line has inspired other writers. Byron wrote, in the same vein, in "Martial, Lib. I, Epig. I" (c. 1821):

He unto whom thou art so partial,

O reader! is the well-known Martial,

The Epigrammatist: while living

Give him the fame thou wouldst be giving;

So shall he hear, and feel, and know it --

Post-obits rarely reach a poet.

The fact I asked you last night

To come round this evening and dine,

Procillus, would seem to be due

To that fifth or sixth bottle of wine.

To think it entirely arranged

And take notes on the nonsense you hear

Is a hazardous way to behave —

D–n a drinker whose memory’s clear![Hesterna tibi nocte dixeramus,

Quincunces puto post decem peractos,

Cenares hodie, Procille, mecum.

Tu factam tibi rem statim putasti

Et non sobria verba subnotasti

Exemplo nimium periculoso:

Μισῶ μνάμονα συμπόταν, Procille.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 27 (1.27) (AD 85-86) [tr. Nixon (1911), “A Alleybi’s the Thing”]

(Source)

"To Procillus." The Greek phrase, attested to elsewhere in Classical literature, reads, as variously translated here, "I dislike a drinking companion who remembers."

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

I had this day carroust the thirteenth cup,

And was both slipper-tong'd, and idle-brain'd,

And said by chance, that you with me should sup.

You thought hereby, a supper cleerely gain'd:

And in your Tables you did quote it up.

Uncivill ghest, that hath been so ill train'd!

Worthy thou are hence supperlesse to walke,

That tak'st advantage of our Table-talke.

[tr. Harington (fl. c. 1600)]

To sup with me, to thee I did propound,

But 'twas when our full cups had oft gone round.

The thing thou straight concludest to be done,

Merry and sober words counting all one.

Th' example's dangerous at the highest rate;

A memorative drunkard all men hate.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Yesternight, it seems, I swore,

Fifty bumpers hardly o'er,

You should sup tonight with me;

Instant you devour'd the glee;

And would bind the words of drink:

Dang'rous precedent, I think.

Wofull partner of the bowl,

Proves a reminiscent soul.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 7, ep. 17]

Last night I had invited you -- after some fifty glasses, I suppose, had been despatched -- to sup with me today. You immediately thought your fortune was made, and took note of my unsober words, with a precedent but too dangerous. I hate a boon companion whose memory is good, Procillus.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Last night I said to you (I think it was after I had got through ten half-pints): "Dine with me today, Procillus." You at once thought the matter settled for you, and took secret note of my unsober remark -- a precedent too dangerous! "I hate a messmate with a memory," Procillus.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

I may have asked you here to dine,

But that was late at night,

And none of us had spared the wine

If I remember right.

You thought the invitation meant,

Though wine obscured my wit!

And -- O most parous precedent --

You made a note of it!

The maxim that in Greece was true

Is true in Rome today --

"I hate a fellow-toper who

Remembers what I say."

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "'Tis Wise to Forget"]

After ten cups were put away

I said, "Procillus," yesterday,

"You'll dine with me, my friend, you're wanted."

You promptly took the thing for granted

And made a note without formality

Of my incautious hospitality;

A dangerous precedent to set;

I hate a guest who won't forget.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #16]

Last night I said, while feeling fine,

Having drunk much too much wine,

That you must promise, when this way,

To stop and dine with me some day.

You made a mental note of it,

A practice which, I must admit --

Taking me at my drunken word! --

Is dangerous and quite absurds.

Barroom promises are fine,

But he who keeps them is a swine!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Last night in my cups,

or my brandy tumbler, at least,

I asked you for dinner today.

But you took me seriously, Procillus,

and noted down carefully the words I spouted

under the influence. A dangerous business.

I don't like to drink with people who remember.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Last night, after five pints of wine,

I said, "Procillus, come and dine

Tomorrow." You assumed I meant

What I said (a dangerous precedent)

And slyly jotted down a note

Of my drunk offer. Let me quote

A proverb from the Greek: "I hate

An unforgetful drinking mate."

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Last night when I was carried off with wine

I made you promise to drop by and dine

With me today. Only a fool or a turd

Expects a drunken man to keep his word.

[tr. O'Connell (1991), "Bummer"]

Last night after getting through four pints or so I asked you to dine with me this evening, Procillus. You thought you had the matter settled then and there, and made a mental note of my tipsy words -- a very dangerous precedent. I don't like a boozing partner with a memory, Procillus.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

When drinks I had beyond my number,

I thought I would myself encumber

With a pledge to give you lunch today.

You wrote it down with great display

As if to register disputed votes.

I hate a tippler taking notes.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Last night, Procillus, after I had drunk

four pints or so, I asked if you would dine

with me today. At once, you thought the matter

was settled, based on statements blurred by wine --

a risky precedent. Good memory

is odious in one who drinks with me.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Last night I invited you,

after we killed, what, fifty-something cups,

to come and eat some food with me today.

Right then and there you thought the thing was done

and took me at my not-so-sober word.

A very risky thing to do: I hate

a drinking bud whose memory is good.

[tr. Goldman (2022)]

Who says with last night’s wine Acerra stinks,

Is much deceived: till day Acerra drinks.[Hesterno fetere mero qui credit Acerram,

Fallitur: in lucem semper Acerra bibit.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 28 (1.28) (AD 85-86) [tr. Wright (1663)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Acerra smells of last night's wine, you say.

Don't wrong Acerra: he topes on till day.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 117]

Whoever believes it is of yesterday's wine that Acerra smells, is mistaken: Acerra always drinks till morning.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Lest you think Afer smells of his yesterday's wine

I give warning

That Afer continues potating each night

Till it's morning.

[tr. Nixon (1911), "By the Book"]

He who fancies that Acerra reeks of yesterday's wine is wrong. Acerra always drinks till daylight.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

He reeks, you might think, of his yesterday's drink;

But knowing his customs and ways,

You are wrong, I'll be sworn, for he drank till the morn,

So the savour is truly today's.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

You say he still reeked of last night's wine

When he spoke to you, stifling a yawn?

Oh no, you are wrong, you're mistaken, sir!

He always drinks till dawn.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Acerra reeks of last night's wine?

No. He drinks on into the sunshine.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Anybody who thinks that Acerra reeks of yesterday's wine misses his guess. Acerra always drinks till sunrise.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

They claimed, with blamings not condign,

He reeked at morn of last night's wine.

He intermits not in such ways:

Not last night's wine -- it was today's.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Whoever thinks Acerra stinks of last night's wine

is wrong. He drinks till light begins to shine.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

To say Acerra stinks of day-old booze is wrong!

Each drink is freshened all night long!

[tr. Juster (2016)]

I do not love thee, Sabidius, nor can I say why;

I can only say this, I do not love thee.[Non amo te, Sabidi, nec possum dicere quare:

Hoc tantum possum dicere, non amo te.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 32 (1.32) (AD 85-86) [tr. Bohn’s (1859)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

I love thee not, Sabidius; ask you why?

I do not love thee, let that satisfy!

[tr. Wright (1663)]

I love thee not, but why, I can't display.

I love thee not, is all that I can say.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

SABBY, I love thee not, nor can say why.

One thing I can say, SAB: thee love not I.

[tr. Elphinston (1782)]

I love you not, Sabidis, I cannot tell why.

This only can I tell, I love you not.

[tr. Amos (1858), 3.86, cited as 1.33]

I do not love you, Sabidius, nor can I say why;

I can only say this, I do not love you.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1897)]

I do not love you, Sabidius; and I can't say why.

This only I can say: I do not love you.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

I like you not, Sabidius, and I can't tell why. All I can tell is this: I like you not.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

I don’t love you, Sabidius, no, I can’t say why:

All I can say is this, that I don’t love you.

[tr. Kline (2006)]

Mister Sabidius, you pain me.

I wonder (some) why that should be

And cannot tell -- a mystery.

You inexplicably pain me.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Sabidius, I dislike you, but why this is so true

I can't say, I can only say I don't like you.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Sabinus, I don’t like you. You know why?

Sabinus, I don’t like you. That is why.

[tr. Cunningham (1971)]

Sabidius, I don't like you. Why? No clue.

I just don't like you. That will have to do.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

There are some variations of this epigram of note. The first is from Thomas Forde (b. 1624):

I love thee not, Nell,

But why I can't tell;

Yet this I know well,

I love thee not, Nell.

[Letter to Thomas Fuller in Virtus Rediviva (1661)]

This seemingly served as a prototype for a more famous variant, attributed to Thomas Brown (1663-1704) (sometimes ascribed to "an Oxford wit") on Dr. John Fell, the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, c. 1670:

I do not like thee, Dr. Fell,

The reason why I cannot tell;

But this, I'm sure, I know full well,

I do not like thee, Dr. Fell.

[Works, Vol. 4 (1774)]

This is sometimes rendered:

I do not love you, Dr. Fell,

But why I cannot tell;

But this I know full well,

I do not love you, Dr. Fell.

Along these same lines:

I do not like you, Jesse Helms.

I can’t say why I’m underwhelmed,

but I know one thing sure and true:

Jesse Helms, I don’t like you.

[tr. Matthews (1995)]

She weeps not for her sire if none be near,

In company she calls up many a tear.

True mourners would not have their sorrows known,

For grief of heart will choose to weep alone.[Amissum non flet cum sola est Gellia patrem,

Si quis adest, iussae prosiliunt lacrimae.

Non luget quisquis laudari, Gellia, quaerit,

Ille dolet vere, qui sine teste dolet.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 33 (1.33) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

"On Gellia." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Gellia ne'er mourns her father's loss,

When no one's by to see,

but yet her soon commanded tears

Flow in society:

To weep for praise is but a feigned moan;

He grieves most truly, that does grieve alone.

[tr. Fletcher (1656)]

When all alone, your tears withstand;

In company, can floods command.

Who mourns for fashion, bids us mark;

Who mourns indeed, mourns in the dark.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Gellia alone, alas! can never weep,

Though her fond father perish'd in the deep;

With company the tempest all appears

And beauteous Gellia's e'en dissolved in tears.

Through public grief though Gellia aims at praise,

'Tis private sorrow which must merit raise.

[Gentleman's Magazine (1736)]

Her father dead! -- Alone no grief she knows;

Th' obedient tear at every visit flows.

No mourner he, who must with praise be fee'd!

But he, who mourns in secret, mourns indeed.

[tr. Hay (1755), 1.34]

Sire-reft, alone, poor Gellia weeps no woe:

In company she bids the torrent flow.

they cannot grieve, who to be seen, can cry:

Theirs is the grief, who without witness sigh.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 6, Part 3, ep. 1]

Gellia, when she is alone, does not lament the loss of her father. If any one be present, her bidden tears gush forth. A person does not grieve who seeks for praise; his is real sorrow who grieves without a witness.

[tr. Amos (1858), #95 "Feigned Tears"]

Gellia does not mourn for her deceased father, when she is alone; but if any one is present, obedient tears spring forth. He mourns not, Gellia, who seeks to be praised; he is the true mourner, who mourns without a witness.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

He grieves not much who grieves to merit praise;

His grief is real who grieves in solitude.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Gellia weeps not while she is alone for her lost father; is any one be present, her tears leap forth at her bidding. He does not lament who looks, Gellia for praise;' he truly sorrows who sorrows unseen.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Gellia, alone, ne'er weeps her sire at all;

In company the bidden tears down fall.

True grief is not for admiration shown.

He only weeps indeed, who weeps alone.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #18, 1.32]

When alone, Gellia never cries for the father she lost.

If someone is with her, tears well up in her eyes,

as if ordered to fall in. If some one looks for praise,

he is not in mourning, Gellia.

He truly mourns

who mourns

alone.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

In private she mourns not the late-lamented;

If someone's by her tears leap forth on call.

Sorry, my dear, is not so easily rented.

They are true tears that without witness fall.

[tr. Cunningham (1971)]

Gellia does not cry for her lost father when she's by herself, but if she has company, out spring the tears to order. Gellia, whoever seeks credit for mourning is no mourner. He truly grieves who grieves without witnesses.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Gellia's mourning for her father?

If by herself she doesn't bother.

But when she sees that company lurks

She opens up the waterworks.

She just wants praise for grief that's shown;

They truly grieve who weep alone.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

When Janet is sequestered, out of view,

Then never for her father's death she cries.

But let some viewers come, just one or two,

Then tears dramatically flood her eyes.

We know from this how sad in fact she's been:

It is not grief that's only grieved when seen.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Gellia doesn't weep for her dead father

when she's alone, but tears pour on command

if someone comes. Who courts praise isn't mourning --

he truly grieves who grieves with none at hand.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Alone, Gellia never weeps over her father's death;

if someone's there, her tears burst forth at will.

Mourning that looks for praise, Gellia, is not grief:

true sorrow grieves unseen.

[tr. Powell]

The verse is mine but friend, when you declaim it,

It seems like yours, so grievously you maim it.[Quem recitas meus est, o Fidentine, libellus:

sed male cum recitas, incipit esse tuus.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 38 (1.38) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

"To Fidentinus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

The Booke thou readst, O Fidentine, is mine;

But when thou ill recit'st it, it proves thine.

[tr. May (1629)]

The verses, Sextus, thou dost read, are mine;

But with bad reading thou wilt make them thine.

[tr. Harington (fl. c. 1600)]

The verses, friend, which thou hast read, are mine;

But, as thou read'st them, they may pass for thine.

[tr. Bouquet]

The verses, friend, which thou hast read, are mine;

But, as thou read'st so ill, 't is surely thine.

[tr. Fletcher (c. 1650)]

My living lays were those that you dispense:

But, when you murder them, they yours commence.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 12.14]

O Fidentinus! the book you are reciting is mine, but you recite it so badly it begins to be yours.

[tr. Amos (1858), ch. 2, ep. 33]

With faulty accents, and so vile a tone,

You quote my lines, I took them for your own.

[tr. Halhead (fl. c. 1800)]

The book which you are reading aloud is mine, Fidentinus but, while you read it so badly, it begins to be yours.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

The verses, friend, which thou has read, are mine;

But, as though read'st them, they may pass for thine.

[tr. Bouquet (<1879)]

You're reading my book to your friends as your own:

But in reading so badly your claim to it's shown.

[tr. Nixon (1911)]

That book you recite, O Fidentinus, is mine. But your vile recitation begins to make it your own.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

The book you read in public from

is one I wrote. But the way you moan

and mangle it turns it into your own.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

They're mine, but while a fool like you recites

My poems I resign the author's rights.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

The little book you are reciting, Fidentinus, belongs to me. But when you recite it badly, it begins to belong to you.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Fame of how badly you read it endures.

Though that's my book, just call it yours.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

Although the lines are mine (their worth assures) --

By badly singing them, you make them yours.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Dear Rud, the book from which you are

giving a reading is mine

but since you read so badly

it's yours.

[tr. Kennelly (2008)]

The book that you recite from, Fidentinus, is my own.

But when you read it badly, it belongs to you alone.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

That little book you're reciting is one of mine, Fidentinus; but you're reciting it so badly, it's turning into one of yours.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

You ask me to recite my poems to you?

I know how you’ll “recite” them, if I do.

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]

That verse is mine, you know, which you’re

Reciting, But you quote it

So execrably, that I believe

I’ll let you say you wrote it

[tr. Wender]

The poems thou are reading, friend, are mine;

But such bad reading starts to make them thine.

[tr. Oliver]

Lest all overlook so tiny a book

And brevity lead to its loss,

I will not refuse such padding to use

As “Τὸν δ̕ ἀπαμειθόμενος.”[Edita ne brevibus pereat mihi cura libellis,

Dicatur potius Τὸν δ᾽ ἀπαμειβόμενος.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 45 (1.45) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921), “Poet’s Padding”]

(Source)

Using a phrase ("to him in answer" or "answering him") that is repeated many, many times in Homer's epics, The Odyssey and The Iliad. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Lest, in air, the mere lightness my distics should toss;

I'd rather sing δ̕ ἀπαμειθόμενος.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 12.216]

That the care which I have bestowed upon what I have published may not come to nothing through the smallness of my volumes, let me rather fill up my verses with Τὸν δ̕ ἀπαμειθόμενος.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Lest his pains should be lost by publishing too short a book, he will fill it up with repetitions, like Homer's well-known verse.

[tr. Paley/Stone (1890)]

That my labor be not lost because published in tiny volumes, rather let there be added Τὸν δ̕ ἀπαμειθόμενος.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

For fear my fount of poetry run dry

"Him answering" is still my cuckoo-cry.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), ep. 24]

To keep my little books from dropping dead

of brevity, I could pad with "... then he said."

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Rather than have my work published in small volumes and so go to waste, let me say "to him in answer."

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You’re rich and young, as all confess,

And none denies your loveliness;

But when we hear your boastful tongue

You’re neither pretty, rich, nor young.[Bella es, novimus, et puella, verum est,

Et dives, quis enim potest negare?

Sed cum te nimium, Fabulla, laudas,

Nec dives neque bella nec puella es.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 64 (1.64) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921), “The Boaster”]

(Source)

"To Fabulla." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Of beautie braue we knowe thou art,

and eke a maide beside:

Abounding eke in wealthe and store,

this ne maie bee denied.

But while to much you praise your self,

and boste you all surmount:

Ne riche, ne faire, Fabulla, nor

A maide we can you counte.

[tr. Kendall (1577)]

You're fayre, I know't; and modest too, 't is true;

And rich you are; well, who denyes it you?

But whilst your owne prayse you too much proclame,

Of modest, rich, and fayre you loose the same.

[17th C Manuscript]

Faire, rich, and yong? how rare is her perfection,

Were it not mingled with one soule infection?

I meane, so proud a heart, so curst a tongue,

As makes her seeme, nor faire, nor rich, nor yong.

[tr. Harington (fl. c. 1600), ep. 291; Book 4, ep. 37 "Of a faire Shrew"]

Th' art faire Fabulla, tis most true,

Rich, yongue, there's none denies thy due.

But whilest thy selfe dost too much boast,

Thy youth, thy wealth, thy beautie's lost.

[tr. May (1629)]

Genteel 't is true, O nymph, you are;

You're rich and beauteous to a hair.

But while too much you praise yourself,

You've neither air, nor charms, nor pelf.

[tr. Gent. Mag. (1746)]

Pretty thou art, we know; a pretty maid!

A rich one, too, it cannot be gainsay'd.

But when thy puffs we hear, thy pride we see;

Thou neither rich, nor fair, nor maid canst be.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 6, Part 3, ep. 48; Bohn labels this as Anon.]

You are pretty, -- we know it; and young, --it is true; and rich, -- who can deny it? But when you praise yourself extravagantly, Fabulla, you appear neither rich, nor pretty, nor young.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Fabulla, it's true you're a fair ingénue,

And your wealth is on every one's tongue:

But your loud self-conceit

Makes people you meet

Think you neither fair, wealthy, nor young.

[tr. Nixon (1911), "The Egoist"]

You are beautiful, we know, and young, that is true, and rich -- for who can deny it? But while you praise yourself overmuch, Fabulla, you are neither rich, nor beautiful, nor young.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You’re beautiful, oh yes, and young, and rich;

But since you tell us so, you’re just a bitch.

[tr. Humphries (1963)]

It's true enough, Fabulla, you are

by you, Fabulla, you aren't rich, or beautiful, or young.

Bovie (1970)]

That you're young, beautiful and rich,

Fabulla, no one can deny.

But when you praise yourself too much,

None of the epithets apply.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

You're beautiful, oh yes, and young, and rich;

But since you tell us so, you're just a bitch.

[tr. Humphries (<1987)]

You are pretty: we know. You are young: true. And rich: who can deny it? But when you praise yourself too much, Fabulla, you are neither rich nor pretty nor young.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You're rich, and young, and beautiful!

It's true, and who can doubt it?

But less and less we feel that pull

The more you talk about it.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

Of debutantes you are beyond compare --

So wealthy, beautiful, and debonair.

Yet you make all this matter not a whit:

Your beauty to undo -- you boast of it.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

You’re lovely, yes, and young, it’s true,

and rich -- who can deny your wealth?

But you aren’t lovely, young or rich,

Fabulla, when you praise yourself.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

When you offered your wife to each passer-by free,

Not a soul ever wanted to try her.

You have learnt wisdom now: kept beneath lock and key

She has crowds of men waiting to buy her.[Nullus in urbe fuit tota qui tangere vellet

Uxorem gratis, Caeciliane, tuam,

Dum licuit: sed nunc positis custodibus ingens

Turba fututorum est: ingeniosus homo es.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 73 (1.73) (AD 85-86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Cayus, none reckned of they wife a poynt,

While each man might, without all let or cumber,

But since a watch o're her thou didst appoint,

Of Customers she hath no little number.

Well, let them laugh hereat that list, and scoffe it,

But thou do'st find what makes most for thy profit.

[tr. Harington (1618)]

Scarce one in all the city would embrace

Thy proffere'd wife, Caecilian, free to have;

But now she's guarded, and lock'd up, apace

Thy custom comes. Oh, thou'rt a witty knave!

[tr. Fletcher (c. 1650)]

Your wife's the plainest piece a man can see:

No soul would touch her, whilst you left her free:

But since to guard her you employ all arts,

The rakes besiege her. -- You're a man of parts!

[tr. Hay (1755), ep. 74]

These was no one in the whole city, Caecilianus, who desired to meddle with your wife, even gratis, while permission was given; but now, since you have set a watch upon her, the crowd of gallants is innumerable. You are a clever fellow!

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

There was no one in the whole town willing to touch your wife, Caecilianus, gratis, while he was allowed; but now you have set your guards, there is a huge crowd of gallants. You are an ingenious person!

[tr. Ker (1919)]

No one in town would touch your wife

so long as she was free, and willing to boot.

But you posted guards, and suddenly brought to life

a swarm of suitors ardent after forbidden fruit

in the garden.

Say, you're a wily warden.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

When you complaisantly allowed Any man, free of charge, to lay Hands on your wife, not one would play. But now you've posted a house guard There's an enormous randy crowd. Caecilianus, you're a card.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Nobody in all Rome would have wanted to lay a finger on your wife gratis so long as it was permitted, Maecilianus; but now you have posted guards, there is a huge crowd of fuckers. You're a smart fellow.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

To screw your wife, unguarded, no one cared.

But once you barred her door, a thousand dared.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

None in all Rome would've wished to touch your wife

for free -- if you permitted it -- not ever.

Now that you've posted guards, Caecilianus,

you've drawn a crowd of fuckers. You're so clever.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

No one in this city would

touch your wife, while free they could;

now she’s guarded, there’s a band

of fuckers for her -- clever man!

[tr. @sentantiq/Robinson (2016)]

Caecilianus,

There wasn’t a guy in this whole damn city

Who would have touched your old lady without a stud fee

When she was easily available.

But now, with all those chaperones you’ve hired,

There’s a pack of cocksmen waiting to bang her.

You sure are clever.

[tr. Salemi]

I muse not that your Dog turds oft doth eat;

To a tongue that licks your lips, a turd’s sweet meat.[Os et labra tibi lingit, Manneia, catellus:

Non miror, merdas si libet esse cani.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 83 (1.83) (AD 85-86) [tr. Davison (1608)]

(Source)

"On Manneia." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

That thy Dog loves to lick thy Lips, th'art pleas'd;

He'll lick that too, of which thy Belly's eas'd;

And not to flatter, and the Truth to smother,

I do believe, he knows not one from t'other.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

On thy lov'd lips, the whelpling lambent hung.

No wonder if a dog can feed on dung.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 171]

Your lap-dog, Manneia, licks your mouth and lips:

I do not wonder at a dog liking to eat ordure.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Your face and lips, Manneia, your little dog licks;

I don't wonder that a dog likes to eat filth.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Your dog licks your mouth and you don't push him from it.

But what says the proverb -- "A dog and his vomit"?

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Your puppy licks your face and your lips:

No wonder, considering the way he also dips

into turds.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Your little dog licks you from head to foot

Am I surprised, Manneia?

Not a bit.

I’m not surprised that dogs like shit.

[tr. O'Connell (1987)]

Manneia, your little dog licks your face and lips. Small wonder that a dog likes eating dung.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Manneia, your lapdog licks his lips with his tongue.

It’s no surprise that a dog likes eating dung.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Dear Manneia:

Your lapdog’s licking your lips and chin:

no wonder with that shit-eating grin.

[tr. Juster (2016)]

Your little puppy licks your mouth and lips --

Manneia, I no longer find it strange

That dogs are tempted by the smell of turds.

[tr. Salemi]

Your puppy licks your mouth and lips

And never wants to quit.

Manneia, I don't wonder why.

All dogs eat their shit.

[tr. Cooper]

That I ne’er saw thee in a Coach with Man,

Nor thy chaste Name in wanton satire met;

That from thy sex thy liking never ran,

So as to suffer a Male-servant yet;

I thought thee the Lucretia of our time:

But, Bassa, thou the while a Tribas wert,

And clashing — with a prodigious Crime

Didst act of Man th’ inimitable part.

What Oedipus this Riddle can untie?

Without a Male there was Adultery.[Quod numquam maribus iunctam te, Bassa, videbam

Quodque tibi moechum fabula nulla dabat,

Omne sed officium circa te semper obibat

Turba tui sexus, non adeunte viro,

Esse videbaris, fateor, Lucretia nobis:

At tu, pro facinus, Bassa, fututor eras.

Inter se geminos audes committere cunnos

Mentiturque virum prodigiosa Venus.

Commenta es dignum Thebano aenigmate monstrum,

Hic ubi vir non est, ut sit adulterium.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 90 (1.90) (AD 85-86) [tr. Sedley (1702)]

(Source)

"To Bassa". This epigram is often untranslated or omitted in collections. Martial thought lesbian sexuality perverse, though he enjoyed and wrote highly of pederasty, as any good Roman male would. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

That with the males thou ne'er wast known to mix,

Nor e'er gallant did envious slander fix;

That thine officious sex thee homag'd round,

And not a man durst taint the hallow'd ground:

What less than a Lucretia could'st thou be?

Ah! what was found? Th' adulterer in thee,

To make the mounts collide emerg'd they plan,

And monstrous Venus would bely the man.

Thou a new Theban torture could'st explore,

And bid adult'ry need a male no more.

[tr. Hay (1755); Book 6, Part 3, ep. 44]

Inasmuch as I never saw you, Bassa, surrounded by a crowd of admirers, and report in no case assigned to you a favoured lover; but every duty about your person was constantly performed by a crowd of your own sex, without the presence of even one man; you seemed to me, I confess it, to be a Lucretia.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1897), "On Bassa"; the "translation" then shifts to the original Latin.]

In that I never saw you, Bassa, intimate with men, and that no scandal assigned you a lover, but every office a throng of your own sex round you performed without the approach of man -- you seemed to me, I confess, a Lucretia; yet, Bassa -- oh, monstrous! -- you are, it seems, a nondescript. You dare things unspeakable, and your portentous lust imitates man. You have invented a prodigy worthy of the Theban riddle, that here, where no man is, should be adultery!

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Never having seen you taking a man's arm, Bassa,

realizing that no gossip attaches a lover to you,

noticing how you were always surrounded

by a throng of your own sex doing things for you

and letting no man approach you, I admit I felt

that we had another Lucretia in you.

But you were doing the raping, Bassa,

working out ways for identical twin genitals

to double their fun by pretending that one -- yours --

was the man in this case, a barefaced lie

you've conjured up a riddle only the Sphinx could solve:

Adultery, without any man involved.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

I never saw you close to men, Bassa, and no rumor gave you a lover. You were always surrounded by a crowd of your own sex, performing every office, with no man coming near you. So I confess I thought you a Lucretia; but Bassa, for shame, you were a fornicator. You dare to join two cunts and your monstrous organ feigns masculinity. You have invented a portent worthy of the Theban riddle: where no man is, there is adultery.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

I never saw you, Bassa, with a man

No rumor ever spread of an affair.

You seemed as chaste as any woman can,

With Lucrece pure you made a worthy pair.

Belatedly I found I venerated,

A woman who a woman penetrated.

You found an amphisbaenic instrument --

To give cunts simultaneous content.

You pose a riddle Sphinxes never knew,

To be a woman and a woman screw.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Bassa, I never saw you hang with guys --

Nobody whispered that you had a beau.

Girls surrounded you at every turn;

They did your errands, with no attendant males.

And so, I guess I naturally assumed

That you were what you seemed: a chaste Lucretia.

But hell no. Why, you shameless little tramp,

You were an active humper all the time.

You improvised, by rubbing cunts together,

And using that bionic clit of yours

To counterfeit the thrusting of a male.

Unbelievable. You’ve managed to create

A real conundrum, worthy of the Sphinx:

Adultery without a co-respondent.

[tr. Salemi (2008)]

Bassa, I never saw you close to men; no gossip linked you to a lover here.

A crowd of your own sex was always with you at every function, no man coming near.

I have to say, I thought you a Lucretia, but you (for shame!) were fucking even then.

You dare link twin cunts and, with your monstrous clitoris, pretend to fuck like men.

You'd suit a Theban riddle perfectly:

where there's no man, there's still adultery.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You damn every poem I write,

Yet you won’t publish those of your own.

Now kindly let yours see the light,

Or else leave my damned ones alone.[Cum tua non edas, carpis mea carmina, Laeli.

Carpere vel noli nostra vel ede tua.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 91 (1.91) (AD 85-86) [tr. Nixon (1911)]

(Source)

"To Lælius". (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thou blam'st my verses and conceal'st thine own:

Or publish thine, or else let mine alone!

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

You do not publish your own verses, Laelius; you criticise mine. Pray cease to criticise mine, or else publish your own.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Although you don't publish your own, you carp at my poems, Laelius. Either do not carp at mine, or publish your own.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You blame my verse; to publish you decline;

Show us your own or cease to carp at mine.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Although you have not published

Even a single line

Of poetry yourself, you scoff

And sneer and jeer at mine.

Get off my back or publish!

I'd like to hear you whine!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Although you don't punish anything, Laelius,

you keep finding fault with my songs. So please,

stop criticizing my stuff, or publish your own.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Although you don't publish your own poems, Laelius, you carp at mine. Either don't carp at mine or publish your own.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Each poem I publish you loudly bemoan.

Unfair that you never share works of your own.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

You don’t write poems, Laelius, you criticise mine. Stop criticising me or write your own.

[tr. Kline (2006)]

With carpings you my works revile.

Your own you never publish.

Without such works, your carpings I'll

Consider snooty rubbish.

[tr. Wills (2007), "The Critic"]

You blast my verses, Laelius; yours aren’t shown.

Either don’t carp at mine or show your own.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You won’t reveal your verse,

but whine that mine is worse.

Just leave me alone

or publish your own.

[tr. Juster (2016)]

You never wrote a poem,

yet criticize mine?

Stop abusing me or write something fine

of your own!

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]

“Write shorter epigrams,” is your advice.

Yet you write nothing, Velox. How concise![Scribere me quereris, Velox, epigrammata longa.

Ipse nihil scribis: tu breviora facis.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 110 (1.110) (AD 85-86) [tr. McLean (2014)]

(Source)

"To Velox." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Velox complains my epigrams are long,

When he writes none: he sings a shorter song.

[tr. Fletcher (c. 1650)]

You say my epigrams, Velox, too long are:

You nothing write; sure yours are shorter far.

[tr. Wright (1663)]

Of my long epigrams, you, Swift, complain;

And nothing write: I laud your shorter strain.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 16, "To Velox, or Swift"]

You complain, Velox, that the epigrams which I write are long. You yourself write nothing; your attempts are shorter.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

You complain, Velox, that I write long epigrams, you yourself write nothing. Yours are shorter.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

"Such lengthy epigrams," you say, "affright one."

True, yours are shorter, for you never write one.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Velox, I make my epigrams too long, you snort?

You don't write any: That's making them too short.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Velox, you complain that I write long epigrams, and yourself write nothing. Do you make shorter ones?

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You say I write lines longer than I ought?

It's true your lines are shorter -- they are nought.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

You say my epigrams are too long.

Yours are shorter.

You write nothing.

[tr. Kennelly (2008), "Nothing"]

Swifty, you moan that I write long epigrams. You aren't writing anything yourself; is that you making shorter ones?

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

My epigrams are word, you've complained;

But you write nothing. Yours are more restrained.

[tr. O'Connell]

“Much too long” you say, Velox, censorious,

Of my epigrams -- that’s quite uproarious.

You write none. Your brevity is glorious.

[tr. Schmidgall (2001)]

You call my epigrams verbose and lacking in concision

while you yourself write nothing. Wise decision.

[tr. Clark, "Short Enough?"]

My epigrams are wordy, you’ve complained;

But you write nothing. Yours are more restrained.

[tr. Oliver]

Paul reads as his own all the poems he buys.

Well, all that he pays for is his, I surmise.[Carmina Paulus emit, recitat sua carmina Paulus.

Nam quod emas, possis iure vocare tuum.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 20 (2.20) (AD 86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

Martial returns to this theme (and Paulus) in epigram 6.12. Original Latin. Alternate translations:

Paulus buys verse, recites, and owns them all,

For what thou buy'st, thou may'st thine truly call.

[tr. Fletcher (1656)]

Bought verses for his own Paul doth recite,

For what you buy you may call yours by right.

[tr. Wright (1663)]

Paul verses buys; and what he buys, recites.

Alike his own are what he buys and writes.

[tr. Elphinson (1782)]

Sly Paul buys verse as he buys merchandise,

Then for his own he'll pompously recite it --

Paul scorns a lie -- the poetry is his --

By law his own, although he could not write it.

[tr. New Monthly Magazine (1825)]

Paulus buys verses; Paulus recites his own verses. And they are his own, for that which you buy, you have a right to call yours.

[tr. Amos (1858), 2.32]

Paullus buys poems, and aloud,

As his, recites them to the crowd.

For what you buy it is well known

You have a right to call your own.

[tr. Webb (1879)]

Paulus buys verses: Paulus recites his own verses; and what you buy you may legally call your own.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1897)]

Paullus buys poems; his own poems he'll recite,

For what he buys is surely his by right.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Paulus buys a book of verse

And reads us then his own.

One's right, of course, to what one buys

Can legally be shown.

[tr. Nixon (1911)]

Paul buys up poems, and to your surprise,

Paul then recites them as his own:

And Paul is right; for what a person buys

Is his, as can by law be shown!

[tr. Duff (1929)]

Paulus buys poems, Paulus recites

his own poems. What you can buy

you are entitled to call your own.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

He buys up poems for recital

And then as "author" reads.

Why not? The purchase proves the title.

our words become his "deeds."

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Paulus buys poems, Paulus recites his poems. For what you buy, you may rightly call your own.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Paulus buys poems; Paulus gives readings from his poems.

After all, what you buy you can rightfully call your own.

[tr. Williams (2004)]

A poet's name is what you sought.

The name, you found, is all you bought.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Paulus buys verse, which he recites as his,

for if the things you buy aren't yours, what is?

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Paul is reciting poems he buys.

At least he doesn’t plagiarize.

[tr. Juster (2016)]

I had hardly thought by asking

For five hundred I’d be tasking

The kindness of a rich old friend like you.

“Practice law,” you said, “it’s healthy,

And it soon will make you wealthy.”

Now, Gaius, tell me “Yes,” not what to do.[Mutua viginti sestertia forte rogabam,

Quae vel donanti non grave munus erat.

Quippe rogabatur felixque vetusque sodalis

Et cuius laxas arca flagellat opes.

Is mihi ‘Dives eris, si causas egeris’ inquit.

Quod peto da, Gai: non peto consilium.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 30 (2.30) (AD 86) [tr. Nixon (1911), “Neither a Borrower”]

(Source)

"To Caius/Gaius." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

When twenty pounds I'd borrow of a friend,

One, who might give me more, as well as lend;

Blest in his fortune; my companion old;

Whose coffers, and whose purse-strings, crack with gold.

"Turn lawyer, and you'll soon grow rich," he cries:

Give me what I ask, my friend: -- 'tis not advice.

[tr. Hay (1755)]

Of sesterces a score I crave in loan,

Which scarce a boon would honest bounty own.

A fortune-blest old intimate I urge,

Whose gen'rous wealth tyrannic coffers scourge.

"Go, ply the bar: be affluent in a trice."

I ask your aid, my Cay, not your advice.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 5, ep. 31]

I asked Caius to lend me twenty sestertia, a sum which could not weigh heavy on him, even if he had been asked to give and not to lend; for he was my old companion, and hd been fortunate in life; and his chest can scarcely press down his overflowing riches. He replied to me, "You will become wealthy if you will take to pleading causes." Caius! give me what I ask for, I do not ask for advice.

[tr. Amos (1858), "Unseasonable Advice"; ch. 3, ep. 89]

I asked, by chance, a loan of twenty thousand sesterces, which would have been no serious matter even as a present. He whom I asked was an old acquaintance in good circumstances, whose money-chest finds difficulty in imprisoning his overflowing hoards. "You will enrich yourself, was his reply, "if you will go to the bar." Give me, Caius, what I ask: I do not ask advice.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

I asked, as it chanced, the loan of twenty thousand sesterces, which, even to a give, would have been no burden. The fact was I asked them of a well-to-do and old friend, and one whose money-chest keeps in control o'erflowing wealth. His answer was, "You will be rich if you plead causes." Give me what I ask, Gaius: I don't ask for advice.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

I chanced to ask a loan -- a hundred, merely;

E'en as a gift that should not task severely

A wealthy friend, and so I asked him, knowing

His pockets bulge with cash over-flowing.

"Go to the Bar," says he, "get rich by pleading" --

'Tis cash, not counsel, Gaius, that I'm needing.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

I asked you twenty thousand as a loan,

A trifle, had I craved it for my own,

Such claim might ancient friendship well afford

On one whose coffers chid their bursting hoard.

"Plead and you'll make a fortune in a trice."

I want your money, Gaius, not advice.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), ep. 79]

I asked a rich old friend of mine

for a loan of twenty thousand:

No trouble at all for him to give it to me,

he was so loaded. But in answer to my request

he said, "You know what? You want to make money?

Become a lawyer." Look, Gaius:

I asked you for money, not for advice.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

I happened to ask a Ioan of twenty thousand sesterces, no burdensome present even as a gift. He of whom I asked it was a faithful old friend, he whose coffer whips up his ample wealth. Says he to me: "You'll be a rich man if you plead cases." Give me what I ask, Gaius; I'm not asking advice.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

I need a loan of twenty grand.

Can you lend a helping hand?

We're friends, it's not a huge amount

Against your massive bank account.

But your reply? "Go practice law,

it's easy to get rich, ha-ha!"

So here's a thought on which to chew:

No job advice I asked from you.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

I chanced to seek a loan of twenty thousand --

which one could give away and not think twice.

The man I asked, a trusted longtime friend,

whose strongbox whips up riches in a trice,

said, "Be a lawyer. You'll make piles of cash."

I asked for money, Gaius, not advice.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You ask me how my farm can pay,

Since little it will bear;

It pays me thus — ‘Tis far away

And you are never there.[Quid mini reddat ager quaeris, Line, Nomentanus?

Hoc mini reddit ager: te, Line, non video.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 38 (2.38) (AD 86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:

Linus, dost ask what my field yields to me?

Even this profit, that I ne'er see thee.

[tr. Fletcher (1656)]

What my farm yields me, doest thou urge to know?

This, that I see not thee, when there I go.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Do you ask what profit my Nomentan estate brings me, Linus? My estate brings me this profit, that I do not see you, Linus.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1860)]

Ask you what my Nomentane fields

Can yield me, Linus, bleak and few?

For me my farm this, Linus, yields;--

That, when I'm there, I'm rid of you.

[tr. Webb (1879)]

You ask what I grow on my Sabine estate.

A reliable answer is due.

I grow on that soil --

Far from urban turmoil --

Very happy at not seeing you.

[tr. Nixon (1911)]

Do you ask, Linus, what my Nomentan farm returns me? This my land returns me: I don't see you, Linus.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You ask of my Nomentan farm

How such a barren waste can charm.

One reason is, I find no trace

There, Linus, of your ugly face.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #83]

Linus, you mock my distant farm,

And ask what good it is to me?

Well, it has got at least one charm --

When there, from Linus I am free!

[tr. Duff (1929)]

You don't see what I see, you say,

In living here so far away?

What I see, Linus, is a view

In which I see no sign of you.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

What return on my real estate at Nomentum?

Up there i get out of seeing you, Linus.

That's what I get out of it.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

You ask me what I get

Out of my country place.

The profit, gross or net,

Is never seeing your face.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Linus, you ask me what I get out of my land near Nomentum. This is what I get out of the land: I don't see you, Linus.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You ask what my estate at Nomentum produces for me? It produces this: that I don't see you, Linus.

[tr. Williams (2003)]

You ask me why I like the country air.

I never meet you there.

[tr. Kennelly (2004), "The Reason"]

You ask what I see in my farm near Nomentum, Linus?

What I see in it, Linus, is: from there I can’t see you.

[tr. Kline (2006)]

What, Linus, can my farm be minus

When it successfully lacks Linus?

[tr. Wills (2007)]

You ask me why I like the country air.

I never meet you there.

[tr. Kennelly (2008)]

What yield does my Nomentan farmstead bear?

Linus, I don’t see you when I am there.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You're wondering what the yield is from my farm at Nomentum, Linus? Here's the yield form my farm: Linus, I don't have to look at you.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

You ask me why I love fresh country air?

You’re not befouling it there.

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]

You ask me why I choose to live elsewhere? You're not there.

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]

Ask you what my Nomentane field brings me?

This, Linus, 'mongst the rest, I ne'er see thee.

[tr. Wright]

You wonder if my farm pays me its share?

It pays me this: I do not see you there.

[tr. Oliver]

You ask me, Roger, what I gain

By living on this barren plain.

This credit to the spot is due,

I live there without seeing you.

[tr. Cowper]

Laugh if you are wise, O girl, laugh.

[Ride, si sapis, o puella, ride.]

Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 41 (2.41.1) (AD 86) [tr. Ker (1919)]

(Source)

"To Maximina." (Source (Latin)).

Martial says he thinks he's quoting Ovid, but it aligns with nothing known or still extant from that poet. As the phrase is hendecasyllabic, and Ovid is not known to have published anything in that meter, it is at the very least believed a paraphrase. It is still usually credited as a fragment for Ovid. It's ironic, since it is the point of this Martial epigram, that in Ars Amatoria 3.279ff, Ovid warns against laughing if one's teeth are bad; see Williams for more discussion.

Alternate translations:

Laugh, my girl, laugh, if you bee wise.

[16th C Manuscript]

Laugh, lovely maid, laugh oft, if thou art wise.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Laugh, my pretty damsel, laugh;

If thou'rt cunning, but by half.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 6, Part 3, ep. 8]

Smile, O damsel, if you are wise, smile.

[tr. Amos (1858), ch. 3, ep. 101]

Laugh if thou art wise, girl, laugh.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Laugh if you are wise, girl, laugh

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1871)]

Laugh, if thou be wise.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

Laugh, maiden, laugh, if thou be wise.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Smile, maiden, smile.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), ep. 86]

Laugh, girl, laugh if you're sensible.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Laugh if you have any sense, girl, laugh.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Laugh, girl; if you're clever, laugh!

[tr. Williams (2004)]

I wanted to love you: you prefer

To have me as your courtier.

Well, I must follow your direction.

But goodbye, Sextus, to affection.[Vis te, Sexte, coli: volebam amare.

Parendum est tibi: quod iubes, coleris:

Sed si te colo, Sexte, non amabo.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 55 (2.55) (AD 86) [tr. Michie (1972)]

(Source)

"To Sextus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

I Offer Love, but thou Respect wilt have;

Take, Sextus, all thy Pride and Folly crave:

But know I can be no Man's Friend and Slave.

[tr. Sedley (1702)]

The more I honour thee, the less I love.

[tr. Johnson (c. 1755)]

Yes, I submit, my lord; you've gained your end:

I'm now your slave -- that would have been your friend;

I'll bow, I'll cringe, be supple as your glove;

-- Respect, adore you -- ev'rything but -- love.

[tr. Graves (1766)]

Sextus, would'st though courted be?

I had hopes of loving thee.

If thou wilt, I must obey;

I shall court thee, nor delay.

Dost thou ceremony seek?

And renounce my friendship? Speak.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 5, ep. 35]

To love you well you bid me know you better,

And for that wish I rest your humble debtor;

But, if the simple truth I may express,

To love you better, I must know you less.

[tr. Byron (c. 1820)]

You wish to be treated with deference, Sextus: I wished to love you. I must obey you: you shall be treated with deference, as you desire. But if I treat you with deference, I shall not love you.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

You wish to be courted, Sextus; I wished to love you. I must obey you; as you demand, you shall be courted. But if I court you, Sextus, I shall not love you.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

I offered love -- you ask for awe;

Then I'll obey you and revere;

But don't forget the ancient saw

That love will never dwell with fear.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

You want my respect, I wanted to love you,

Sextus. I give in. Have my respect.

But I cannot prefer someone I defer to.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

You would be courted, dear, and I would love you.

But be it as you will, and I will court you.

But if I court you, dear, I will not love you.

[tr. Cunningham (1971)]

You want to be cultivated, Sextus. I wanted to love you. I must do as you say. Cultivated you shall be, as you demand. But if I cultivate you, Sextus, I shall not love you.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

I would love you, dear, by preference,

But you instead demand my deference.

And so my love I will defer,

With courtesy, as you prefer.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

You ask for deference when I offer love;

So be it; you shall have my bended knee.

But Sextus, by great Jupiter above,

Getting respect, you'll get no love from me.

[tr. Hill]

You want to be my patron and my friend.

If you insist on patron, goodbye friend!

[tr. Wills (2007)]

I wished to love you; you would have

me court you. What you want must be.

But if I court you, as you ask,

Sextus, you'll get no love from me.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

You have robbed the young gallant of nostrils and ears,

And his face now of both is bereft.

But your vengeance remains incomplete it appears;

He has still got another part left.[Foedasti miserum, marite, moechum,

Et se, qui fuerant prius, requirunt

Trunci naribus auribusque voltus.

Credis te satis esse vindicatum?

Erras: iste potest et irrumare.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 83 (2.83) (AD 86) [tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thou hast deform'd the poor gallant;

Nor could they justice mercy grant.

His nose so slit and ear so tore,

Now seek in vain the grace they wore.

Now vengeance boasts her ample due.

Fool! mayn't the foe the charge renew?

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 6.2.34]

Husband, you have disfigured the wretched gallant, and his countenance, deprived of nose and ears, regrets the loss of its original form. Do you think that you are sufficiently avenged? You are mistaken: something still remains.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

You have disfigured, O' husband, the wretched adulterer, and his face, shorn of nose and ears, misses its former self. Do you believe you are still sufficiently avenged? You mistake; he still has other activities.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

The cuckold finally caught the culprit,

Boxed his ears and broke his jaw.

But hasn't he missed the point?

[tr. Murray (1967)]

Oh husband, you have disfigured your wife's

unhappy seducer; with his nose and ears your knife's

satisfied its user. How his face misses

its familiar features! This revenge, it meets your

requirements? He can still ram it up their asses.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

You took a dire revenge, one hears,

On him who stole your wife,

By cutting off his nose and ears --

It's marred his social life.

Still there's one thing you didn't get

And that could cause you trouble yet.

[tr. O. Pitt-Kethley (1987)]

Husband, you mutilated your wife's unhappy lover, and his face, maimed of nose and ears, misses its former self. Do you suppose you are sufficiently avenged? You err. He can also give suck.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

You have disfigured your wife's unfortunate lover, O husband: his face, deprived of nose and ears, vainly seeks its former state. Do you think you have sufficiently taken revenge? You're wrong. The man can also fuck in the mouth.

[tr. Williams (2004)]

The man gave you the cuckold's horn?

His ears and nose your knife has shorn.

Have you deprived him of a screw?

Just ask his mouth what it can do.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Husband, you maimed your wife's poor lover.

Shorn of its nose and ears, his face

looks vainly for its former grace.

Do you believe you've done enough?

You're wrong. He still can be sucked off.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

‘Tis hard bewildering riddles to compose

And labour lost to work at nonsense prose.[Turpe est difficiles habere nugas,

Et stultus labor est ineptiarum.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 86 (2.86.9-10) (AD 86) [tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #105]

(Source)

Discussing writing elaborate or highly stylized poetry forms. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Disgraceful 't is unto a poet's name

Difficult toys to make his highest am:

The labour's foolish that doth rack the brains

For things have nothing in them, but much pains.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

How foolish is the toil of trifling cares.

[tr. Johnson (1750); he credits the translation Elphinston]

How pitifull the boast of petty feats!

How idle is the toil of mean conceits!

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 2.76]

It is disgraceful to be engaged in difficult trifles; and the labour spent on frivolities is foolish.

[tr. Amos (1858), 2.19]

It is absurd to make one's amusements difficult; and labor expended on follies is childish.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

'Tis mean and foolish to assign

Long care and pains to trifles light.

[tr. Webb (1879)]

Disgraceful ’tis to treat small things as difficult;

‘Tis silly to waste time on foolish trifles.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

'Tis degrading to undertake difficult trifles; and foolish is the labour spent on puerilities.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

'Tis hard bewildering riddles to compose

And labor lost to work at nonsense prose.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924)]

It's demeaning to make difficulties out of trifles, and labor over frivolities is foolish.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

It is absurd to make trifling poetry difficult, and hard work on frivolities is foolish.

[tr. Williams (2004)]

The Latin phrase was used by Addison as the epigram of The Spectator #470 (29 Aug 1712).

You recite no verse, Mamercus, but claim you write.

Claim what you like — so long as you don’t recite.[Nil recitas et vis, Mamerce, poeta videri.

Quidquid vis esto, dummodo nil recites.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 2, epigram 88 (2.88) (AD 86) [tr. McLean (2014)]

(Source)

"To Mamercus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

You'd Poet seem, yet nothing you rehearse:

Be what you will, so we ne'er hear your verse.

[tr. Wright (1663)]

Thou would'st a poet be, yet nought dost write:

Be what thou wilt, so nought thou dost indite.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Arthur, they say, has wit. "For what?

For writing?" No -- for writing not.

[tr. Swift (early 18th C)]

Nought you recite, and would be pris'd a poet?

Be what you will, so no reciting blow it.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 12.18]

You don't recite, but would be deemed a poet;

You shall be Homer -- so you do not show it.

[tr. Byron (early 19th C)]

You don't recite; but still would seem a poet.

You shall be Homer, so you do not show it.

[tr. Byron (early 19th C), alt.]

You recite nothing, and you wish, Mamercus, to be thought a poet. Be whatever you will, only do not recite.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Though you never have read us a line of your verse,

You insist on our thinking you write.

Yes, yes, be a poet; be anything else --

If only you'll forbear to recite.

[tr. Nixon (1911)]

You recite nothing, and yet wish, Mamercus, to be held a poet. Be what you like -- provided you recite nothing.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You never recite, though you pose as a poet.

Well, for that many thanks: we will gladly forgo it.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

You'd like to be thought of as a poet

but refuse to recite your material?

Be what you want, Mammercus; the public

will tolerate you so long as you don't inflict

your verse on public nerves.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

You recite nothing and want to be considered a poet, Mamercus. Be what you like, so long as you recite nothing.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

In the verse Cinna writes

I am slandered, it’s said.

But the man doesn’t write

Whose verses aren’t read.[Versiculos in me narratur scribere Cinna.

Non scribit, cuius carmina nemo legit.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 3, epigram 9 (3.9) (AD 87-88) [tr. Nixon (1911)]