The uses of a dictionary: at thirteen we look up lewd, licentious, lascivious; at thirty, febrile and inchoate; at fifty, endostosis.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 10 (1963)

(Source)

Quotations about:

youth

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Don’t spurn sweet love,

my child, and don’t you be neglectful

of the choir of love, or the dancing feet,

while life is still green, and your white-haired old age

is far away with all its moroseness. Now,

find the Campus again, and the squares,

soft whispers at night, at the hour agreed,

and the pleasing laugh that betrays her, the girl

who’s hiding away in the darkest corner,

and the pledge that’s retrieved from her arm,

or from a lightly resisting finger.

[Nec dulcis amores

sperne puer neque tu choreas,

donec virenti canities abest

morosa. Nunc et campus et areae

lenesque sub noctem susurri

conposita repetantur hora,

nunc et latentis proditor intumo

gratus puellae risus ab angulo

pignusque dereptum lacertis

aut digito male pertinaci.]Horace (65-8 BC) Roman poet and satirist [Quintus Horacius Flaccus]

Odes [Carmina], Book 1, # 9, l. 15ff (1.9.15-24) (23 BC) [tr. Kline (2015)]

(Source)

"To Thaliarchus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Till testy Age gray Hairs shall snow

Upon thy Head, lose Mask, nor Show:

Soft whispers now delight

At a set hour by Night:

And Maids that gigle to discover

Where they are hidden to a Lover;

And Bracelets or some toy

Snatcht from the willing Coy.

[tr. Fanshaw (Brome (1666))]

Secure those golden early joys,

That youth unsoured with sorrow bears,

Ere withering time the taste destroys,

With sickness and unwieldy years.

For active sports, for pleasing rest,

This is the time to be possest;

The best is but in season best.

The appointed hour of promised bliss,

The pleasing whisper in the dark,

The half unwilling willing kiss,

The laugh that guides thee to the mark;

When the kind nymph would coyness feign,

And hides but to be found again;

These, these are joys the gods for youth ordain.

[tr. Dryden (c. 1685)]

Whilst Thou art green, and gay, and Young,

E're dull Age comes, and strength decays,

Let mirth, and humor, dance, and song

Be all the trouble of thy days.

The Court, the Mall, the Park, and Stage,

With eager thoughts of Love pursue;

Gay Evening whispers fit thy Age,

And be to Assignation true.

Now Love to hear the hiding Maid,

Whom Youth hath fir'd, and Beauty charms

By her own tittering laugh betray'd,

And forc'd into her Lover's Arms.

Go dally with thy wanton Miss,

And from the Willing seeming Coy,

Or force a Ring, or steal a Kiss;

For Age will come, and then farewell to joy.

[tr. Creech (1684)]

Sport in life's young spring,

Nor scorn sweet love, nor merry dance,

While years are green, while sullen eld

Is distant. Now the walk, the game,

The whisper'd talk at sunset held,

Each in its hour, prefer their claim.

Sweet too the laugh, whose feign'd alarm

The hiding-place of beauty tells,

The token, ravish'd from the arm

Or finger, that but ill rebels.

[tr. Conington (1872)]

Nor disdain, being a young fellow, pleasant loves, nor dances, as long as ill-natured hoariness keeps off from your blooming age. Now let both the Campus Martius and the public walks, and soft whispers at the approach of evening be repeated at the appointed hour: now, too, the delightful laugh, the betrayer of the lurking damsel from some secret corner, and the token ravished from her arms or fingers, pretendingly tenacious of it.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]

Let beauty's glance

Engage thee, and the merry dance,

Nor deem such pleasures vain!

Gloom is for age. Young hearts should glow

With fancies bright and free,

Should court the crowded walk, the show,

And at dim eve love's murmurs low

Beneath the trysting tree;

The laugh from the sly corner, where

Our girl is hiding fast,

The struggle for the lock of hair,

The half well pleased, half angry air,

The yielded kiss at last.

[tr. Martin (1864)]

Spurn not, thou, who art young, dulcet loves;

Spurn not, thou, choral dances and song

While the hoar-frost morose keeps aloof from thy verdure.

Thine the sports of the Campus, the gay public gardens;

Thine at twilight the words whispered low;

Each in turn has its own happy hour:

And thine the sweet laugh of the girl -- which betrays her

Hiding slyly within the dim nook of the threshold,

And the love-token snatched from the wrist,

Or the finger's not obstinate hold.

[tr. Bulwer-Lytton (1870)]

Youth must not spurn

Sweet loves, nor yet the dance forsake,

While grudging Age thy prime shall spare.

The Plain, the Squares, be now thy care,

And lounges, dear at nightfall, where

By concert love may whisper 'Hist!'

From inner nook a winsome smile

Betrays the girl that sculks the while,

And keepsakes, deftly filched by guile

From yielding finger, or from wrist.

[tr. Gladstone (1894)]

Nor, while thy vigour lasts, despise thou

Pleasures of love, nor the joys of dancing.

While the moroseness due to advancing age

Whitens not yet thy head, let the walks and park

And gentle whispers heard at nightfall

Each be repeated at fitting seasons.

Now, too, the pleasant laughter be heard, that tells

How lurking beauty hides in the corner-nook,

And token ravish'd from the arm, or

Finger, that daintily seems unwilling.

[tr. Phelps (1897)]

Being but yet a youth, contemn

Neither the sweets of love nor of the dance,

While from your bloom crabbed greyness holds aloof.

Now let the Campus and the city squares,

And whispers low, be sought at nightfall,

On the appointed hour of tryst;

And now the fascinating laugh from some recess

Secluded, the betrayer of a maid

In hiding, and the pledge snatched off

An arm or finger ill retaining it.

[tr. Garnsey (1907)]

Spurn not the dance,

Or in sweet loves to bask,

While surly age mars not thy morning's flower.

Seek now the athlete's training field or court;

See gentle lovers' whispered sport,

At nightfalls's trysted hour;

Seek the gay laught that from her ambush borne

Betrays the merry maiden huddled warm,

And forfeit from her hand or arm

Half given, half playful torn.

[tr. Marshall (1908)]

Nor in thy youth neglect sweet love nor dances, whilst life is still in its bloom and crabbed age is far away! Now let the Campus be sought and the squares, with low whispers at the trysting-hour as night draws on, and the merry tell-tale laugh of maiden hiding in farthest comer, and the forfeit snatched from her arm or finger that but feigns resistance.

[tr. Bennett (Loeb) (1912)]

Scorn not, while still

A boy, sweet loves; scorn not the dance.

Life in its Spring, and crabbed eld

Far off -- that is the time; then hey

For Park, Square, whispered concerts held

At a set hour at close of day:

For the sweet laugh whose soft alarm

Tells in what nook the maid lies hid:

For the love-token snatched from arm,

Of fingers that but half-forbid.

[tr. Mills (1924)]

Now that you're young, and peevish

Grey hairs are still far distant, attend to the

Dance-floor, the heart's sweet business; for now is the

Right time for midnight assignations,

whispers and murmurs in Rome's piazzas

And fields, and soft, low laughter that gives away

The girl who plays love's games in a hiding-place --

Off comes a ring coaxed down an arm or

Pulled from a faintly resisting finger.

[tr. Michie (1963)]

Take love while you're young and you can,

Laugh, dance,

Before time takes your chances

Away. Stroll where baths, where theaters

Bring Romans to walk, to talk, where whispers

Flit through the darkness as lovers meet,

And girls laugh from hidden corners,

Happy as favors

Are snatched in the darkness, laugh

And pretend to say no.

[tr. Raffel (1983)]

While you're still young,

And while morose old age is far away,

There's love, there are parties, there's dancing and there's music,

There are young people out in the city squares together

As evening comes on, there are whispers of lovers, there's laughter.

[tr. Ferry (1997)]

Do not disdain, boy, sweet love; and dance

while you are yet in bloom, and crabbed age far away.

Now frequent the Campus Martius

and public ways, and pizzas where soft whispers

are repeated at the trysting hour

and where the suffocated laughter of a girl

lurking in a corner reveals

secret betrayal and the forfeit

snatched away from a wrist

or from a finger, scarcely resisting.

[tr. Alexander (1999)]

And while you're young don't scorn

sweet love affairs and dances,

so long as crabbed old age is far from

your vigor. Now let the playing field and the

public squares and soft whisperings at nightfall

(the appointed hour) be your pursuits;

now too the sweet laughter of a girl hiding

in a secret corner, which gives her away,

and a pledge snatched from her wrists

or her feebly resisting finger.

[tr. Wikisource (2021)]

Someday we will regard our children not as creatures to manipulate or to change but rather as messengers from a world we once deeply knew, but which we have long since forgotten, who can reveal to us more about the true secrets of life, and also our own lives, than our parents were ever able to.

Alice Miller (1923-2010) Polish-Swiss psychologist, psychoanalyst, philosopher

For Your Own Good [Am Anfang war Erziehung], “Preface to the American Edition” (1980) [tr. Hannum/Hannum (1983)]

(Source)

SYPHAX: Young men soon give and soon forget affronts;

Old age is slow in both.Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Cato, Act 2, sc. 5, l. 136ff (1713)

(Source)

Youth is not a time of life; it is a state of mind; it is not a matter of rosy cheeks, red lips and supple knees; it is a matter of the will, a quality of the imagination, a vigor of the emotions; it is the freshness of the deep springs of life.

Youth means a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity of the appetite, for adventure over the love of ease. This often exists in a man of sixty more than a boy of twenty. Nobody grows old merely by a number of years. We grow old by deserting our ideals.

Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul. Worry, fear, self-distrust bows the heart and turns the spirit back to dust.

Whether sixty or sixteen, there is in every human being’s heart the lure of wonder, the unfailing child-like appetite of what’s next, and the joy of the game of living.

When the aerials are down, and your spirit is covered with snows of cynicism and the ice of pessimism, then you are grown old, even at twenty, but as long as your aerials are up, to catch the waves of optimism, there is hope you may die young at eighty.

Samuel Ullman (1840-1924) German-American businessman, poet, humanitarian, religious leader

“Youth” (1918)

(Source)

This poem was a favorite of Douglas MacArthur, who had a copy hung in his office in Tokyo, and was responsible for much of the author's subsequent fame in Japan.

When a twelfth-century youth fell in love he did not take three paces backward, gaze into her eyes, and tell her she was too beautiful to live. He said he would step outside and see about it. And if, when he got out, he met a man and broke his head — the other man’s head, I mean — then that proved that his — the first fellow’s — girl was a pretty girl. But if the other fellow broke his head — not his own, you know, but the other fellow’s — the other fellow to the second fellow, that is, because of course the other fellow would only be the other fellow to him, not the first fellow who — well, if he broke his head, then his girl — not the other fellow’s, but the fellow who was the — Look here, if A broke B’s head, then A’s girl was a pretty girl; but if B broke A’s head, then A’s girl wasn’t a pretty girl, but B’s girl was. That was their method of conducting art criticism.

Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) English writer, humorist [Jerome Klapka Jerome]

Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow, “On Being Idle” (1886)

(Source)

Nothing — so it seems to me — is more beautiful than the love that has weathered the storms of life. The sweet, tender blossom that flowers in the heart of the young — in hearts such as yours — that, too, is beautiful. The love of the young for the young, that is the beginning of life. But the love of the old for the old, that is the beginning of — of things longer.

Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) English writer, humorist [Jerome Klapka Jerome]

“Passing of the Third Floor Back” [The Stranger] (1908)

(Source)

Still you say, the young man has the hope of long life — a hope which the old cannot have. That hope is sheer wishful thinking, for what is more irrational than to count the uncertain as certain, the false as true? But the old man has nothing to look forward to at all. Even so, he is in better sort than the young, for he has obtained what the young only hope for: the young want to live a long life; the old have lived it.

[At sperat adulescens diu se victurum, quod sperare idem senex non potest. Insipienter sperat; quid enim stultius quam incerta pro certis habere, falsa pro veris? At senex ne quod speret quidem habet. At est eo meliore condicione quam adulescens, quoniam id quod ille sperat hic consecutus est: ille volt diu vivere, hic diu vixit.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 19 / sec. 68 (19.68) (44 BC) [tr. Copley (1967)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

But ye may saye that the man adolescent & yong hopith that he shall lyve longe & aftir that a man is olde he may not have such an hope. Therfor I answere you that the yong man hopith foliously if by cause of his yong age he wenith to live long, for he is not certayn therof nor knowith not the trouthe. Now ther is nothyng more foly thene is for to have & holde the doubtuose thyngys as certayn & the fals as true & if ye oppose agenst olde age that the olde man hath nothyng in hym whereby he may hope to lyve more, I answere you, Scipion & Lelius, that by this thyng is bettir the condicion & the astate of the olde man than of the yong man, for the yong man will lyve long & the olde man hath lyved long.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]

But a young man hopeth to live long, which an old man may not look to do. He truly feedeth himself with a vain and a foolish, hope. For what merer folly can there be, than to accompt and repute things which be doubtful and uncertain, for infallible and certain, and things that are false, for true? An old man hath nothing to hope for; but he is therefore in far better state and case than is a young man, for he hath already enjoyed and obtained that, which the young man doth but hope for. The one desireth to live long, the other hath already lived long.

[tr. Newton (1569)]

But the young man hopes to live long, which the old man cannot. He hopes foolishly; for what is greater folly, then to account uncertain things for certain, false for true? The old man hath nothing to hope for more; therefore he is in better state then the former, seeing that what the other wisheth for, he hath obtained already; the young man would live long, the old man hath lived long.

[tr. Austin (1648), ch. 21]

But vigorous Youth may his gay thoughts erect

To many years, which Age must not expect,

But when he sees his airy hopes deceiv'd,

With grief he saies, who this would have believ'd?

We happier are then they, who but desir'd

To possess that, which we long since acquir'd.

[tr. Denham (1669)]

But Youth, you'll say perhaps, may live in Hopes of Length of Days, when we are deprived even of all Hope. A childish Hope this indeed! To hold Uncertainties for Certainties, and Falsity for Truth! Old Age, you say, has not even Hope for its Relief; but, even in that Respect, is it not far preferable to Youth, in being actually possessed of what the other only hopes for? Long Life is sure on the one side, and only wished for on the other.

[tr. Hemming (1716)]

But the young Man is in Hopes of Living long, which the Old cannot. I must tell him he hopes foolishly; for, can there be a greater Instance of Folly than to make sure of Uncertainties; or embrace Falsities for Truth? The Old Man has nothing more to hope for; then he is in a better State than the Young one, since what this hopes for, the other has already attain'd: The one is in Hopes of Living long, the other has done it.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

It may however be said, perhaps, that Youth has Room at least to hope they have Length of Life before them, which in Old Men would be vain. But foolish is that Hope: For what can be more absurd, than to build on utter Uncertainties, and account on that for sure, which probably may never happen? And to what is alleged, that the Old Man has no Room lest for Hope, I say, Just so much the happier is his Condition, than that of the Young; because he has already attained, and is sure of what the other only wishes and hopes for: The one wishes to live long, the other is at the End of that Wish, he has got it; for he has lived long already.

[tr. Logan (1744)]

It will be replied, perhaps, that "youth may at least entertain the hope of enjoying many additional years; whereas an old man cannot rationally encourage so pleasing an expectation." But is it not a mark of extreme weakness to rely upon precarious contingencies, and to consider an event as absolutely to take place, which is altogether doubtful and uncertain? But admitting that the young may indulge this expectation with the highest reason, still the advantage evidently lies on the side of the old; as the latter is already in possession of that length of life which the former can only hope to attain.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

But a young man hopes that he shall live long; which same thing an old man cannot hope. He hopes absurdly. For what is sillier than to hold uncertainties for certainties, the false for true? An old man has not even what he may hope; but he is by that in a better condition than the young man, since that which the former hopes for, the latter has attained. The former wishes to live long; the latter has lived long.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

Yet a young man hopes that he will live a long time, which expectation an old man cannot entertain. His hope is but a foolish one: for what can be more foolish than to regard uncertainties as certainties, delusions as truths? An old man indeed has nothing to hope for; yet he is in so much the happier state than a young one; since he has already attained what the other is only hoping for. The one is wishing to live long, the other has lived long.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

But, it is said, the young man hopes to live long, while the old man can have no such hope. The hope, at any rate, is unwise; for what is more foolish than to take things uncertain for certain, false for true? Is it urged that the old man has absolutely nothing to hope? For that very reason he is in a better condition than the young man, because what the youth hopes he has already obtained. The one wishes to live long; the other has lived long.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

Yes, you will say; but a young man expects to live long; an old man cannot expect to do so. Well, he is a fool to expect it. For what can be more foolish than to regard the uncertain as certain, the false as true? "An old man has nothing even to hope." Ah, but it is just there that he is in a better position than a young man, since what the latter only hopes he has obtained. The one wishes to live long; the other has lived long.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

But you will say the young

Have hope of life, which is to us denied.

A foolish hope. For what more foolish is

Than where no surety is to think things sure,

Where all is doubtful to believe them fixed?

Granted the old man cannot even hope:

'Tis all the better since he has attained

To what the young man only hopes to gain:

The one desires long life, the other's lived.

[tr. Allison (1916)]

But, you may say, the young man hopes that he will live for a long time and this hope the old man cannot have. Such a hope is not wise, for what is more unwise than to mistake uncertainty for certainty, falsehood for truth? They say, also, that the old man has nothing even to hope for. Yet he is in better case than the young man, since what the latter merely hopes for, the former has already attained; the one wishes to live long, the other has lived long.

[tr. Falconer (1923)]

There is a crucial difference between a young man and an old one: the one hopes for a long life yet to come, and the other knows that his time is nearly up. But a hope is only a hope: what is more foolish than to confuse what is uncertain with what is certain, and what is false with what is true? The young man who lives in a state of great expectations is much worse off than the old man who looks forward to nothing. One can only dream of what the other has accomplished: one wants to live a long time, but the other already has.

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]

But, you say, that is not the point. The point is that a young person can reasonably hope to live a long time and an old one cannot. What an unwise hope. I mean, what is more follish than to value uncertainty above certainty? Look at life this way, what the young person only hopes for (and the hope is uncertain, as we have seen), the old person already has. The one hopes to live a long time, the other has already done so.

[tr. Gerberding (2014)]

But they say a young man hopes in a long lease

Of life while an old man awaits its surcease.

Taking certain for uncertain is a wish,

Like taking false for true, completely foolish.

But, they add, even at the end of the rope

An old man is in a better shape than a young man

For he has already fulfilled his life’s hope.

One wants the long life the other had in full measure,

ut dear gods what is “long” in man’s nature?

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

But you may argue that young people can hope to live a long time, whereas old people cannot. Such hope is not wise, for what is more foolish than to mistake something certain for what is uncertain, or something false for what is true? You might also say8 that an old man has nothing at all to hope for. But he in fact possesses something better than a young person. For what youth longs for, old age has attained. A young person hopes to have a long life, but an old man has already had one.

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

But the young person hopes to live for a long time, a very hope which the old person cannot hold. They hope unwisely for what is more foolish than to take uncertainty for certainty and falsehood for truth. They claim also that the old person has nothing to hope for. But the elderly are in a better place than the young because the young merely hope for what the elderly have obtained and the one wishes to live long, while the other has already done so.

[tr. @sentantiq (2021)]

Let others, then, have their weapons, their horses and their spears, their fencing-foils, and games of ball, their swimming contests and foot-races, and out of many sports leave us old fellows our dice and knuckle-bones. Or take away the dice-box, too, if you will, since old age can be happy without it.

[Sibi habeant igitur arma, sibi equos, sibi hastas, sibi clavam et pilam, sibi natationes atque cursus; nobis senibus ex lusionibus multis talos relinquant et tesseras; id ipsum ut lubebit, quoniam sine eis beata esse senectus potest.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 16 / sec. 58 (16.58) (44 BC) [tr. Falconer (1923)]

(Source)

The actual gaming objects for old folk that Cicero refers to were the talus (a long four-sided die) and the tessera (a six-sided die). Various games were played rolling these, on their own or together.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Yong men have for them for theyr solas & worship, their armours, their horsys, their speris, pollaxis mallys, and Instrumentys of iren, or of leed, and launcegayes for to fyght. And also maryners in vsyng the see and yong men deliten in shippys bargys of dyvers fassions and in rowynges and in sayllyng in watirs and ryvers and in the sees, and som yong men usen the cours of voyages in gooyng rydyng and iourneyeng from one counttre to anothir, and emong many othir labours of playes sportys and of dyvers solacys. The yong men also levyn to the use of olde men the playe at the tablis and chesse and the philosophers playe by nombre of arsmetrike as is made mencion in the boke of O∣vide de vetula callid the reformacion of his life. But we demaunde the Caton, if the olde men may goodly use and when we be olde of thies two said playes of the tablis and chesse, I answere you nay, for withoute thies two playes ol̄de age may wele be stuffid and fulfillyd of alle othir goodnes perteynyng to felicite and to blessidnesse. Now it is so that olde age and yche othir age usyng of discression ought not to doo any thyng, but that it drawe and be longe to vertues and to blessidnesse in stede of playes at tables and at chesses.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]

Let us therefore bid adieu to all such youthly pranks and exercises as lusty and green-headed gallants, agitated and pricked with the fervent heat of unadvised adolescence, do enure themselves withal: God speed them well with their usual disports and dalliance; let them take to themselves their armour, weapons, and artillery; let us permit and give them good leave to daunt fierce horses and with spears in rest to mount on courageous coursers; let them handle the pike, toss the javelin and club daily, and play at the tennis, exercise themselves with running, swimming, and such-like deeds of activity and nimbleness. To us old men among all their other games and pastimes, let them leave the tables, the chance-bone or dice, and the chess, which without any danger or sore straining of the body may be practiced. And yet I will not seem to allow these last-named games further than every man himself is disposed, because they be not necessary, and old age may without them be blessed and fortunate.

[tr. Newton (1569)]

Therefore young men have their weapons, their horses, their speares, their swimming, the ball, the club, and their races, and they leave to us old men the cards and the tables which we sometimes use when we list; for age may be right happy without them.

[tr. Austin (1648)]

Let those of younger Years take to themselves all the Diversions of their several sorts of Gaming, Fencing, Racing, or Bathing can afford them: leave us to our Chesse-boards, and our Tables; and yet we are not solicitous even for those, since the Happiness of old Age does not depend on them.

[tr. Hemming (1716)]

Let therefore the young have their Arms, Horse, Spears, Lances, Balls, Baths, and Races; and of their many Diversions, leave to us the Cards and the Tables, to make use of just when we please; for Old Age can be happy without them.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

To others therefore we can freely resign all other Diversions, in Arms and Horses, with their military Exercises, and all their Accoutrements, their Tennis, and every other Sport; only, if they please, they may leave us Checquers and Tables; or even these also we can give up; since Old Age can be very easy and very happy without any such trifling Amusements.

[tr. Logan (1744)]

In respect to the peculiar articles of rural diversions, let those of a more firm and vigorous age enjoy the robust sports which are suitable to that season of life; let them exert their manly strength and address in darting the javelin, or contending in the race; in wielding the bat, or throwing the ball; in riding, or in swimming; but let them, out of the abundance of their many other recreations, resign to us old fellows the sedentary games of chance. Yet if they think proper even in these to reserve to themselves an exckisive right, I shall not controvert their claim; they are amusements by no means essential to a philosophic old age.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

Therefore let them keep to themselves their arms, horses, spears, cudgel, ball, swimming, and running; and let them leave to us old men, out of so many sports, our astragals and dice; and that very thing whether it shall be to our mind, since old age can be happy without these things.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

Let the young, therefore, keep to themselves their arms, horses, spears, clubs, tennis-ball, swimmings, and races: to us old men let them leave out of many amusements the tali and tessera; and even in that matter it may be as they please, since old age can be happy without these amusements.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

Let others take for their own delight arms, horses, spears, clubs, balls, swimming-bouts, and foot-races. From their many diversions let them leave for us old men knuckle-bones and dice. Either will serve our turn; but without them old age can hardly be contented.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

Let the young keep their arms then to themselves, their horses, spears, their foils and ball, their swimming baths and running path. To us old men let them, out of the many forms of sport, leave dice and counters; but even that as they choose, since old age can be quite happy without them.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

Let who will keep their arms, their steeds, their spears,

Their club and ball, and let them swim and run,

But let them leave from many forms of sport

The dice to us old men, or take them too

If so they will: old age can do without

These trifles, and enjoy full happiness.

[tr. Allison (1916)]

No, let young people keep their equipment, their horses, their spears, their foils, their ball-games, their swimming and running, and out of all their amusements let them leave to us old fellows just the knuckle-bones and dice -- and then only if it strikes their fancy, for old age can be quite happy without them.

[tr. Copley (1967)]

You won't find us [old men] in armor or on horseback throwing spears; we don't fence with sticks or play catch; we'll let other people compete with each other in running or swimming races. Maybe we'll gamble a little with dice or knucklebones, or maybe not -- but, in any case, we'll be perfectly content.

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]

Therefore let others keep their fast cars, speed boats, fitness centers, bats, rackets, and balls, and leave us our checkers and bridge cards. But you know, they can take those too if we have a nice garden.

[tr. Gerberding (2014)]

Let the young have arm and mount

Let them have ball and stick and pike

Let them swim and scurry too,

To the old are paramount

Only dice games and the like.

Should they deem those games undue

We’ll comply without ado.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

Let others have their weapons, their horses, their spears and fencing foils, their balls, their swimming contests and food traces. Just leave old men like me our dice and knucklebones. Or take away those too if you want. Old age can be happy without them.

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

Let others have weapons, horses, spears, fencing-foils, ball games, swimming competitions, races, and leave to the old men dice and knucklebones for games. Or let that go too since old age can be happy without it.

[tr. @sentantiq (2018)]

We come now to the third ground for abusing old age, and that is, that it is devoid of sensual pleasures. O glorious boon of age, if it does indeed free us from youth’s most vicious fault! Now listen, most noble young men, to what that remarkably great and distinguished man, Archytas of Tarentum, said in an ancient speech repeated to me when I was a young man serving with Quintus Maximus at Tarentum: “No more deadly curse,” said he, “has been given by nature to man than carnal pleasure, through eagerness for which the passions are driven recklessly and uncontrollably to its gratification. From it come treason and the overthrow of states; and from it spring secret and corrupt conferences with public foes. In short, there is no criminal purpose and no evil deed which the lust for pleasure will not drive men to undertake. Indeed, rape, adultery, and every like offence are set in motion by the enticements of pleasure and by nothing else; and since nature — or some god, perhaps — has given to man nothing more excellent than his intellect, therefore this divine gift has no deadlier foe than pleasure; for where lust holds despotic sway self-control has no place, and in pleasure’s realm there is not a single spot where virtue can put her foot.”

[Sequitur tertia vituperatio senectutis, quod eam carere dicunt voluptatibus. O praeclarum munus aetatis, si quidem id aufert a nobis, quod est in adulescentia vitiosissimum! Accipite enim, optimi adulescentes, veterem orationem Archytae Tarentini, magni in primis et praeclari viri, quae mihi tradita est cum essem adulescens Tarenti cum Q. Maximo. Nullam capitaliorem pestem quam voluptatem corporis hominibus dicebat a natura datam, cuius voluptatis avidae libidines temere et effrenate ad potiendum incitarentur. Hinc patriae proditiones, hinc rerum publicarum eversiones, hinc cum hostibus clandestina colloquia nasci; nullum denique scelus, nullum malum facinus esse, ad quod suscipiendum non libido voluptatis impelleret; stupra vero et adulteria et omne tale flagitium nullis excitari aliis illecebris nisi voluptatis; cumque homini sive natura sive quis deus nihil mente praestabilius dedisset, huic divino muneri ac dono nihil tam esse inimicum quam voluptatem. Nec enim lubidine dominante temperantiae locum esse, neque omnino in voluptatis regno virtutem posse consistere.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 12 / sec. 39ff (12.39-41) (44 BC) [tr. Falconer (1923)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Nowe folowith the iij vituperacion & defaute by the which yong men seyne that olde age is noiouse myschaunte & wretchid by cause it hath almost no flesshely delectacyons or sensualitees as for to gete with childeren and yssue to encrece and multiplie the world. To whom I answere forwith that it is right a noble gyfte rewarde & the right grete worship of olde age that it be sequestred depryved and dischargid of the delectacyons of sensualitee of the body or flesshely lustis for ys it be so that olde age be pryved and sequestred of such delectacyons It had takin awey from us olde men that thyng whiche is right vicious & right foule in the age of adolescence & yongthe.

And neverthelesshe my right good and lovyng yong men Scipion and Lelius an auncyent senatour purposid an oracion that a philosopher callid Archites made whiche was takyn of Haniballe duc of Cartage when he werrid in Ytaile. He was recoverde by Quintus Fabius the noble senatour when he recoverd Tarente, takyn by the said Haniballe. Archites was pryncypally a grete man connyngly lernyd in sciences and in vertues and was right famous and noble. This oracion purposid which Archites made was yeven to me when I adolescent and yong of age was at Tarente with the seid Fabius, and by this oracyon seid Archites that nature which ordeyned to men complexions gave nevir no pestelence peyne nor turment more damageable to yong men than is flesshely delectacyon. The coveitous playsirs of delectacyon moven tyce and steeren men over boldely and withoute bridell of reason or shame or any restraynt to execute and make an ende of their foule lustys. For thought delectacy∣ons ben made and conspired treasons divisions and dissencyons of countrees & the destruccions of their comon profite, and the secretes of parlementys disclosed to our ennemyes and adversarye partye there is noon untrou∣the there is noon evyll werke but pleasyre of delectacyon which shall constrayne men to encline therto, by cause that they enioyen owt of mesure of spousehode brekyng & that so fervently the cause of defoulyng of maydens virgins the anontry of weddyd women & all such corrupte untrew werkys, whiche ben nevir mevid nor undirtakyn but by the insolence & wantownes & wenlacys of flesshely delectacyon. Archites also saide that as nature by power of which god hath yeven to men noth̄yng bettir than is the soule by the which they have undirstondyng & mynde, also to that soule which is an office & a gift dyvine nothyng is so grete ennemye nor so contrary as ben flesshely delectacyons, for sith delectacyon & flesshely pleasir have dominacyon in the regyon of man. That is to witt in the courage of his body, the vertue of attemperance may not be lodgid therin & wthin the regyon of man which is yeven to delectacyon may not abyde any wisedome nor vertue.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]

Now followeth the third dispraise and fault which is laid in old age, because (say they) it is without pleasure, and must forego voluptuous appetites. O noble and excellent gift, wherewith old age is so blessed, if it take from us that thing, which is in youth most vicious and detestable. But you (noble and virtuous gentlemen, Scipio and Laelius) hear what Archytas, the famous philosopher of Tarentum, was wont to say, whose oration touching on the same matter was lent and delivered to me, when I was a young man and served under Quintus Maximus at the siege of Tarentum. He said that no plague was given by nature so great and pernicious unto men, as the bestial pleasures and voluptuousness of the body: which which pleasures the dissolute and libidinous lusts of men do so much affect and desire, that with all licentious profanation and outrage, their minds be incited and stirred to pursue the same, thinking all things lawful for their unbridled appetites, so that they may enjoy their beastly desires and still wallow in the filthy puddle of their hellish sensuality. Hence (said he_ as from a fountain do spring out all kinds of mischief, as treason, betraying of countries, the ruin and subversion of commonwealths, secret conventicles, and privy conferences with the enemies; finally (he said), there was none so great a villainy, nor any so flagitious and horrible an enormity, which the inordinate desire of pleasure would not egg and prick forward men's froward wills to enterprise: furthermore, that whoredom, adultery, and all such like heinous facts of carnal concupiscency were by none other lures or enticements provoked but by pleasure. And whereas either nature or God hath given unto man nothing of so noble excellency as the mind or reasonable soul, there is nothing so great an enemy until this inestimable and divine gift as pleasure.

For where pleasure beareth away and ruleth the roast, there is no mansion or dwelling-place left for temperance and sobriety, and, to be short, virtue cannot remain where pleasure reigneth.

[tr. Newton (1569)]

There followeth the third Objection to age; they say that it wanteth pleasures. Oh excellent gift of age, if it take away that which makes our youth vitious; therefore hear now, O yee excellent young men, the old oration of Architas the Tarentine, a singular and worthy man, which was delivered me when I was a young man with Q. Maximus at Tarentum. He said that there was no deadlier plague given by nature to men, then the pleasure of the body, the greedy lusts whereof are rash and unbrideledly, stirred up to get and gain. From hence are derived treasons, from hence arise the overthrowes of Commonwealths, and the privy conspiracies and whisperings with the enemies. That to conclude, there was no wickednesse, nor no evill deed, to the undertaking of which, the lust of pleasure did not incite a man; and that whoredome, adultery, and all such evill was stirred up by no other bait then pleasure. And forasmuch as nature, or some God, hath given nothing more excellent to a man, then his minde; to this divine gift, there is no greater enemy then pleasure. For lust bearing rule, there is no place for temperance, neither in the Kingdome of pleasure can virtue consist.

[tr. Austin (1648)]

Now must I draw my forces 'gainst that Host

Of Pleasures, which i'th' Sea of age are lost.

Oh, thou most high transcendent gift of age!

Youth from its folly thus to disengage.

And now receive from me that most divine

Oration of that noble Tarentine,

Which at Tarentum I long since did hear;

When I attended the great Fabius there.

Yee Gods, was it man's Nature? or his Fate?

Betray'd him with sweet pleasures poyson'd bait?

Which he, with all designs of art, or power,

Doth with unbridled appetite devour;

And as all poysons seek the noblest part,

Pleasure possesses first the head and heart;

Intoxicating both, by them, she finds,

And burns the Sacred Temples of our Minds.

Furies, which Reasons divine chains had bound,

(That being broken) all the World confound.

Lust, Murder, Treason, Avarice, and Hell

It self broke loose; in Reason's Pallace dwell,

Truth, Honour, Justice, Temperance, are fled,

All her attendants into darkness led.

But why all this discourse? when pleasure's rage

Hath conquer'd reason, we must treat with age.

Age undermines, and will in time surprize

Her strongest Forts, and cut off all supplies.

And joyn'd in league with strong necessity,

Pleasure must flie, or else by famine die.v [tr. Denham (1669)]

The third Accusation against Old Age is, that it deprives us of the Enjoyments of Pleasure. O glorious Priviledge of Age, if through thy means we can get rid of the most pernicious Bane, to which our You is liable! Give me leave to repeat to you, what a great Orator has said upon this Subject.

"Nature has not implanted in Man any more execrable Curse, than that of bodily Pleasures; to the gratification of which we are hurried on, wich such unbounded and licentious Appetites. For to what else is oweing the Subversion of so many States and Kingdoms? What Villainy too daring, what Undertaking too hazardous, which the Desire of satisfying our unbounded Lusts will not instigate us to attempt? To what are Rapes, Adulteries, or such like abominable Enormities owing, but to the gratification of our Appetites? And since the Faculties of Reason, and Judgment, are the most excellent Qualities, which Nature, or Providence, has conferred upon us; it is certain that nothing can be more destructive, more pernicious to this divine Gift, than the Indulging bodily Pleasures? For it is impossible to observe an Degrees of Temperance, while we are under the Dominion of our unruly Passions, nor can Virtue consiste with the pursuit of such Enjoyments."

[tr. Hemming (1716)]

We come now to the Third Objection, which is, That Old Age is deprived of Pleasure. O excellent State! if it deprives us of what is most vitious in You! For, hear ye well-disposed young Men, the old Remark of Architas the Tarentine, a most ingenious Man, which was given to me when I was a young Fellow at Tarentum, with Q. Maximus. He said, "That Nature had not given Mankind a greater Plague than the Pleasure of the body, whose eager Desires for the Enjoyment of it, are altogether loose and unbridled: That from hence arise Conspiracies against our Country, Subversions of the Commonwealth, and treasonable Conferences with the Enemy. In short, that there was no Wickedness nor Capital Crime, but this Lust after Pleasure would put a man upon undertaking; that Whoredom, Adultery, and all such Vices, were excited by no other Allurements than those of Pleasure. That as Nature, or some God, had given to Man nothing more valuable than his Mind, so to that Gift was joined nothing so much its Enemy as Pleasure; for when Lust is predominant, there is no Room for Temperance; nor can Virtue possibly consist in Pleasure's Throne."

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

The third Charge against Old-Age was, That it is (they say) insensible to Pleasure, and the Enjoyments arising from the Gratifications of the Senses. And a most blessed and heavenly Effect it truly is, if it eases of what in Youth was the sorest and cruellest Plague of Life. Pray listen, my good Friends, to an old Discourse of Archytas the Tarentine, a great and excellent Man in his Time, which I learned when I was but young myself, at Tarentum, under Fabius Maximus, at the Time he recovered that Place. The greatest Curse, the heaviest Plague, said he, derived on Man from Nature, is bodily Pleasure, when the Passions are indulged, and strong inordinate Desires are raised and set in Motion for obtaining it. For this have Men betray'd their Country; for this have States and Governments been plunged in Ruin; for this have treacherous Correspondences been held with publick Enemies: In short, there is no Mischief so horrid, no Villany so execrable, that this will not prompt to perpetrate. And as Adultery, and all the Crimes of that Tribe, are the natural Effects of it; so of course are all the fatal Consequences that ensue on them. 'Tis owned, that the most noble and excellent Gift of Heaven to Man, is his Reason: And 'tis as sure, that of all the Enemies Reason has to engage with, Pleasure is the most capital, and the most pernicious: For where its great Incentive, Lust, prevails, Temperance can have no Place; nor under the Dominion of Pleasure, can Virtue possibly subsist.

[tr. Logan (1750)]

Let us now proceed to examine the third article of complaint against old age, as "bereaving us," it seems, "of the sensual gratifications." Happy effect indeed, if it deliver us from those snares which allure youth into some of the worst vices to which that age is addicted. Suffer me upon this occasion, my excellent young friends, to acquaint vou with the substance of a discourse which was held many years since by that illustrious philosopher Archytas, of Tarentum, as it was related to me when I was a young man in the army of Quintus Maximus, at the siege of that city. "Nature," said this illustrious sage, "has not conferred on mankind a more dangerous present than those pleasures which attend the sensual indulgences; as the passions they excite are too apt to run away with reason, in a lawless and unbridled pursuit of their respective enjoyments. It is in order to gratify inclinations of this ensnaring kind that men are tempted to hold clandestine correspondence with the enemies of the state, to subvert governments, and turn traitors to their country. In short, there is no sort of crimes that afiect the public welfare to which an inordinate love of the sensual pleasures may not directly lead. And as to vices of a more private tendency -- rapes, adulteries and every other flagitious violation of the moral duties -- are they not perpetrated solely from this single motive? Reason, on the other hand," continued Archytas," is the noblest gift which God, or nature, has bestowed on the sons of men. Now nothing is so great an enemy to that divine endowment, as the pleasures of sense. For neither temperance, nor any other of the more exalted virtues, can find a place in that breast which is under the dominion of the voluptuous passions."

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

The third charge against old age comes next, namely, that they say that it is without pleasures. O glorious privilege of old age, if indeed it takes away from us that which in youth is most faulty! For listen, excellent young men, to an ancient discourse of Archytas of Tarentum, a singularly great and renowned man, which was delivered to me when I was a young man with Quintus Maximus: He said, that no deadlier plague than the pleasure of the body was given to men by Nature; of which pleasure the passions being excessively fond, impelled men to enjoy them rashly and precipitously. That hence rose betrayals of country, hence subversions of states, hence clandestine correspondence with enemies. In a word, that there is no atrocity, no wicked deed, to the undertaking of which the lust of pleasure did not incite; and that seductions and adulteries, and every such crime, are called into existence by no other allurements but pleasure; and whereas, whether Nature or some deity had given nothing to man more excellent than the understanding, nothing was more hostile to this divine gift and endowment than pleasure. For neither, when lust bore sway, was there room for temperance, nor could virtue hold any place at all in the reign of pleasure.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

Then follows the third topic of blame against old age, that they say it has no pleasures. Oh, noble privilege of age! if indeed it takes from us that which is in youth the greatest defect. For listen, most excellent young men, to the ancient speech of Archytas of Tarentum, a man eminently great and illustrious, which was reported to me when I, a young man, was at Tarentum with Quintus Maximus. He said that no more deadly plague than the pleasure of the body was inflicted on men by nature; for the passions, greedy of that pleasure, were in a rash and unbridled manner incited to possess it; that hence arose treasons against one's country, hence the ruining of states, hence clandestine conferences with enemies: in short, that there was no crime, no wicked act, to the undertaking of which the lust of pleasure did not impel; but that fornications and adulteries and every such crime, were provoked by no other allurements than those of pleasure. And whereas either nature or some god had given to man nothing more excellent than his mind; that to this divine function and gift, nothing was so hostile as pleasure: since where lust bore sway, there was no room for self-restraint; and in the realm of pleasure, virtue could by no possibility exist.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

I come now to the third charge against old age, that, as it is alleged, it lacks the pleasures of sense. O admirable service of old age, if indeed it takes from us what in youth is more harmful than all things else! For I would have you hear, young men, an ancient discourse of Archytas of Tarentum, a man of great distinction and celebrity, as it was repeated to me when in my youth I was at Tarentum with Quintus Maximus. "Man has received from nature," said he, "no more fatal scourge than bodily pleasure, by which the passions in their eagerness for gratification are made reckless and are released from all restraint. Hence spring treasons against one's country; hence, overthrows of states; hence, clandestine plottings with enemies. In fine, there is no form of guilt, no atrocity of evil, to the accomplishment of which men are not driven by lust for pleasure. Debaucheries, adulteries, and all enormities of that kind have no other inducing cause than the allurements of pleasure. Still more, while neither Nature nor any god has bestowed upon man aught more noble than mind, nothing is so hostile as pleasure to this divine endowment and gift. Nor while lust bears sway can self-restraint find place, nor under the reign of pleasure can virtue have any foothold whatever."

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

The third charge against old age is that it LACKS SENSUAL PLEASURES. What a splendid service does old age render, if it takes from us the greatest blot of youth! Listen, my dear young friends, to a speech of Archytas of Tarentum, among the greatest and most illustrious of men, which was put into my hands when as a young man I was at Tarentum with Q. Maximus. "No more deadly curse than sensual pleasure has been inflicted on mankind by nature, to gratify which our wanton appetites are roused beyond all prudence or restraint. Fornications and adulteries, and every abomination of that kind, are brought about by the enticements of pleasure and by them alone. Intellect is the best gift of nature or God: to this divine gift and endowment there is nothing so inimical as pleasure. For when appetite is our master, there is no place for self-control; nor where pleasure reigns supreme can virtue hold its ground."

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

Thirdly, it is alleged against old age,

It has no sensual pleasures to enjoy.

Divinest gift of age, to take away sensual pleasures.

What is the greatest blot on youthful years!

Hear, my dear friends, a speech Archytas made

(Who was a very old and famous man),

And told me at Tarentum, where I was

With Quintus Maximus, when quite a youth:

'No greater curse than sensuality

Has Nature given to man: its foul desires

To feed, lust grows unbridled and unwise;

Hence countries are betrayed, states overthrown,

Secret arrangements with our foes are made.

There is no crime, no ill deed to which lust

Cannot entice : abominable vice

Of every kind is due to this alone.

Nature herself, or some kind deity

Has given to man no greater gift than mind:

But to this gift, this faculty divine,

No greater enemy can be than lust.

When that bears sway, all moderation's gone,

And 'neath its rule virtue cannot survive.

[tr. Allison (1916)]

Next we come to the third allegation against old age. This was its deficiency in sensual pleasures. But if age really frees us from youth's most dangerous failing, then we are receiving a most blessed gift.

Let me tell you, my dear friends, what was said years ago by that outstandingly distinguished thinker, Archytas of Tarentum, the city at which I heard of his words when I was a young soldier serving under Fabius. "The most fatal curse given by nature to mankind," said Archytas, "is sensual greed: this incites men to gratify their lusts heedlessly and uncontrollably, thus bringing about national betrayals, revolutions, and secret negotiations with the enemy. Lust will drive men to every sin and crime under the sun. Mere lust, without any additiona impulse, is the cause of rape, adultery, and every other sexual outrage. Nature, or a god, has given human beings a mind as their outstanding possession, and this divine gift and endowment has no worse foe than sensuality. For in the realm of the physical passions there can be no room for self-control; where self-indulgence reigns, decent behavior is excluded.

[tr. Grant (1960, 1971 ed.)]

I turn now to the third charge against old age -- one commonly leveled with vehemence: men say that it is cut off from pleasures. What a glorious blessing the years confer if they take away from us the greatest weakness that afflicts our younger days! Let me repeat to you, my dear young friends, what Archytas of Tarentum said many, many years ago. (He was one of the truly great -- a distinguished man -- and his discourse was reported to me when as a young man I visited Tarentum in the company of Quintus Maximus.) Archytas declared that nature had afflicted man with no plague more deadly than physical pleasure, since the hope of pleasure roused men’s desires to fever-pitch and spurred them on, like wild, unbridled beasts, to attainment.

Pleasure, he said, was the ultimate source of treason, of riot and rebellion, of clandestine negotiations with an enemy; to sum it up, there was no crime, no foul perversion, which men were not led to commit by the desire for pleasure. As for crimes of passion, adultery, and the like, he declared that pleasure and its blandishments were the sole cause of them "Here is man," said he. "Nature, or if you will, God, has given him nothing more precious and distinctive than his mind, yet nothing is so hostile to this blessing -- this godlike power -- as pleasure."

Further, he asserted that when the appetites had the upper hand there was no room left for self-discipline -- in fact, to put it generally, virtue could find no foothold anywhere in the kingdom of pleasure.

[tr. Copley (1967)]

Now I come to the third reason why old age is so strenuously condemned: that when we are old we can’t enjoy sensual pleasures. On the contrary, what a gift it is that age takes away from us the most objectionable vices of the young! When I was a young man in the army, someone quoted to me from a speech -- and it is well worth listening to it today -- that was delivered long ago by a distinguished philosopher, Archytas of Tarentum. “Nature,” he said, “has never visited on man a more virulent pestilence than sex. There is nothing we will not do, however rash and ill-considered, in order to satisfy our desires. Sex has impelled men to treason, to revolution, to collusion with the enemy. Under the influence of sex, there is no criminal enterprise they will not undertake, no sin they will not commit. Infidelity, of course, and then any kind of depraved perversion you can think of -- all are driven by the search for sexual pleasure. Nature -- or perhaps some god -- has given us nothing more valuable than the power to reason; but there is nothing more inimical to reason than sex. Lust will always overcome self-control; there is no moral value that can stand up to the attacks of unbridled desire.”

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]

THEY SAY OLD AGE DEPRIVES US OF ALMOST ALL OF THE PLEASURES. Oh, this is a wonderful gift of old age, if it does indeed relieve us of most of the reasons youth gets itself into trouble. Remember, you young folks, the famous warning from Dr. Johnson, the especially great and famous eighteenth century savant. I came to admire him when I was a young man at Oxford. He said that the body is all vice. The body's avid desire for the pleasures makes it seek them rashly and without control until it finds gratification. Oh the trouble! These things often create traitors of their countries: they ruin governments and cause secret dealings with enemies. The desire for bodily pleasure drives people to commit debauchery, adultery, and crimes of all sorts. Since nature's (or God's) greatest gift to mankind is our reason, nothing is so harmful to God's gift than the desire for pleasure because it makes us act so irrationally. By golly, when we are in hot pursuit of pleasure, there is no place for modration or good sense. If the pleasure is too great and lasts too long, it will blot out any trace of rational thinking.

[tr. Gerberding (2014)]

Again old age is given a third censure.

It is devoid, they say, of sensual pleasure,

But that’s also a wonderful gift without price

Taking from us youth’s most wicked vice!

Listen, my good lads, to the time-honoured advice

Of Archytas from Tarentum, great and blessed,

Who in my young days his thoughts expressed,

While I was in Tarentum with Q. Maximus:

No evildoing can be worse than the voluptuous

Pleasure of the senses was his complaint

Which makes men blind and act with no restraint.

From it descend treason, revolution and

Pacts with the enemies of the Fatherland.

All evil actions and crimes combined

Have an urge for lust not far behind,

And then adultery and lewdness

Are set on fire by voluptuousness.

There must have been some god who gave mankind,

Or maybe it wasn’t a god but nature,

The divine privilege of the mind

Which is the enemy of pleasure.

Indeed under the rule of passion

Temperance has no place at all,

And virtue can be kept in thrall

By sensuality’s enticing coils.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

We come now to the third objection to growing older -- that the pleasures of the flesh fade away. But if this is true, I say it is indeed a glorious gift that age frees us from youth's most destructive failing. Now listen, my most noble young friends, to the ancient words of that excellent and most distinguished young man, Archytas of Tarentum, repeated to me when I was serving as a young soldier in that very city with Quintus Maximus. He said the most fatal curse given to men by nature is sexual desire. From it spring passions of uncontrollable and reckless lust seeking gratification. From it come secret plotting with enemies, betrayals of one's country, and teh voer throw of governments. Indeed, there is no evil act, no unscrupulous deed that a man driven by lust will not perform. Uncontrolled sensuality will drive men to rape, adultery, and every other sexual outrage. And since nature -- or perhaps some god -- has given men no finer gift than human intelligence, this divine endowment has no greater foe than naked sensuality. Where lust rules, there is no place for self-control. And in the kingdom of self-indulgence, there is no room for decent behavior.

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

The third typical criticism of old age follows this, and that is that people complain that it lacks [sexual] pleasures. Oh! Glorious wealth of age, if it takes that from us, the most criminal part of youth! Take this from me, most noble young men, this is the ancient speech of Archytas of Tarentum, which was repeated to me when I was a young man working for Quintus Maximus there: “Nature has given man no deadlier a curse than sexual desire.”

[tr. @sentantiq (2019)]

My son, young men’s arms are indeed taut for action, but old men’s counsels are better; for time teaches the most subtle lessons.

Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bellerophon [Βελλεροφῶν], frag. 291 (TGF) (c. 430 BC) [tr. Collard, Hargreaves, Cropp (1995)]

(Source)

Alternate translation:

Son, the hands of young men always itch for action, but the

judgment of the old is sounder.

Time teaches discrimination

[tr. Stevens (2012)]

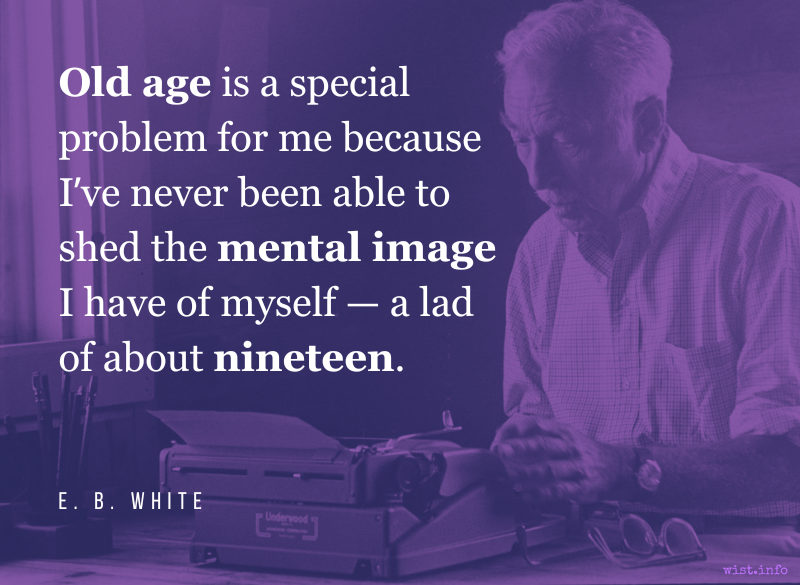

Old age is a special problem for me because I’ve never been able to shed the mental image I have of myself — a lad of about nineteen.

E. B. White (1899-1985) American author, critic, humorist [Elwyn Brooks White]

“E. B. White: Notes and Comment by Author,” interview by Israel Shenker, New York Times (1969-07-11)

(Source)

On his 70th birthday.

So strong is custom formed in early years.

[Adeo in teneris consuescere multum est.]

Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

Georgics [Georgica], Book 2, l. 272ff (2.272) (29 BC) [tr. Greenough (1900)]

(Source)

Discussing how, when transplanting vines, wise farmers try to match the soil and orientation of the plant toward the sun to the conditions where they first sprouted. The same phrase is often extended (when extracted like this) to the lasting effects of early training on children. See also Pope.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Such strength hath custome in each tender soule.

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]

So strong is Custom; such Effects can Use

In tender Souls of pliant Plants produce.

[tr. Dryden (1709), ll. 366-367]

So strong is habit's force in tender age.

[tr. Nevile (1767), l. 302]

So custom strongly sways the youthful year.

[tr. Sotheby (1800)]

Of such avail is custom in tender years.

[tr. Davidson (1854)]

So custom lords it o'er the youthful wood.

[tr. Blackmore (1871), l. 324]

Such is the force of habits formed in early years.

[tr. Wilkins (1873)]

So strong is custom formed in early years.

[tr. Rhoades (1881)]

So powerful is habit in things of tender age.

[tr. Bryce (1897)]

So strong is the habit of infancy.

[tr. Mackail (1899)]

So potent is early habit's control.

[tr. Way (1912)]

So loth to change

Are a young creature's ways.

[tr. Williams (1915)]

So strong is habit in tender years.

[tr. Fairclough (Loeb) (1916)]

So important are habits developed in early days.

[tr. Day-Lewis (1940)]

For habit dominates the early stage.

[tr. Bovie (1956)]

So much effect has habit on the young.

[tr. Wilkinson (1982)]

We grow accustomed to so much in tender years.

[tr. Kline (2001)]

How powerful the innate habits of tender plants!

[tr. Lembke (2004)]

So powerfully runs habit in the tender stems.

[tr. Johnson (2009)]

Such is the need, when young, of what's familiar.

[tr. Ferry (2015)]

The course of a man’s life is certain. The path that we follow goes in only one direction. Every mile is distinctly marked with its own peculiar characteristic — the vulnerability of infants, the animal high spirits of adolescents, the seriousness of adults, the maturity of old men — and at each of these stages we must accept gracefully what Nature grants us.

[Cursus est certus aetatis et una via naturae eaque simplex, suaque cuique parti aetatis tempestivitas est data, ut et infirmitas puerorum et ferocitas iuvenum et gravitas iam constantis aetatis et senectutis maturitas naturale quiddam habet, quod suo tempore percipi debeat.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 10 / sec. 33 (10.33) (44 BC) [tr. Cobbold (2012)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

The cours and the weye of age is certeyne and determyned by nature, whiche hathe onely awey which is symple & is nothyng different more in the one than in the othir. But each go by that symple and determyned wey aftir the degrees in their cours from the one age in to that other. And yet nature had given to every part of age his owne propre season and tyme, and hir pertynent cours of usage in kynde. That is to witt, that sekenesse and maladye is appropryd to the age of puerice in childhode, & cruelte is appropryd to the age of yongth, worshipfulnesse and sadnesse of maners be appropryd to the age of virilite whiche is the fyfthe age. Moderaunce and temperaunce be appropryd to olde age. Eueriche oweth to have sumwhat naturelly and appropryd unto that whiche may be gadird in his tyme.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481), Part 3]

The race and course of age is certain; and there is but one way of nature and the same simple; and to every part of a man's life and age are given his convenient times and proper tempestivities. For even as weakness and infirmity is incident to young children, lustiness and bravery to young men, and gravity when they come to ripe years; so, likewise the maturity or ripeness of old age have a certain special gift given and attributed to it by nature, which ought not to be neglected, but to be taken in his own time and season when it cometh.

[tr. Newton (1569)]

There is but one course of age, and one way of nature, and the same simple, and to every part of age its own timelines is given; for as infirmity belongs to child-hood, fiercenesse to youth, and gravity to age, so the true ripenesse of age hath a certaine natural gravity in it, which ought to be used in it own time.

[tr. Austin (1648)]

Simple, and certain Nature's wayes appear,

As she sets forth the seasons of the year.

So in all parts of life we find her truth,

Weakness to childhood, rashness to our youth:

To elder years to be discreet and grave,

Then to old age maturity she gave.

[tr. Denham (1669)]

Every Age has something in it, peculiar to it self: as Weakness to our Infancy, an unguided Warmth to Youth, Seriousness to Manhood, and a certain Maturity of Judgment to Old Age, which we may expect to reap the Fruits of, when advanced to it.

[tr. Hemming (1716)]

Life has a sure Course, and Nature but one Way, that that too simple and plain. And to every Part of Man's Age a peculiar Propriety of Temper is given: Thus Weakness in Children, a Boldness in Youth, and a Gravity in Manhood appears; and a full Ripeness of Years has always something which seems natural to it, and which ought to be made use of at a proper Time.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]

The Stages of Life are fixed; Nature is the same in all, and goes on in a plain and steady Course: Every Part of Life, like the Year, has its peculiar Season: As Children are by Nature weak, Youth is rash and bold; staid Manhood more solid and grave; and so Old-Age in its Maturity, has something natural to itself, that ought particularly to recommend it.

[tr. Logan (1750)]

Nature conducts us, by a regular and insensible progression through the different seasons of human life; to each of which she has annexed its proper and distinguishing characteristic. As imbecility is the attribute of infancy, ardour of youth, and gravity of manhood; so declining age has its essential properties, which gradually disclose themselves as years increase.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]

The course of life is fixed, and the path of nature is one, and that simple. And its own proper seasonableness has been given to each division of life; so that both the feebleness of boys and the proud spirit of young men, and the gravity of a now settle period of life, and the maturity of old age, has something natural to it, which ought to be gathered in its own season.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]

There is a definite career in life, and one way of nature, and that a simple one; and to every part ot life its own peculiar period has been assigned: so that both the feebleness of boys, and the high spirit of young men, and the steadiness of now fixed manhood, and the maturity of old age, have something natural, which ought to be enjoyed in their own time.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]

Life has its fixed course, and nature one unvarying way; each age has assigned to it what best suits it, so that the fickleness of boyhood, the sanguine temper of youth, the soberness of riper years, and the maturity of old age, equally have something in harmony with nature, which ought to be made availing in its season.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]

The course of life is fixed, and nature admits of its being run but in one way, and only once; and to each part of our life there is something specially seasonable; so that the feebleness of children, as well as the high spirit of youth, the soberness of maturer years, and the ripe wisdom of old age -- all have a certain natural advantage which should be secured in its proper season.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]

One only way

Nature pursues, and that a simple one:

To each is given what is fit for him.

The boy is weak: youth is more full of fire:

Increasing years have more of soberness:

And as in age there is a ripeness too.

Each should be garnered at its proper time,

And made the most of.

[tr. Allison (1916)]

Life's race-course is fixed; Nature has only a single path and that path is run but once, and to each stage of existence has been allotted its own appropriate quality; so that the weakness of childhood, the impetuosity of youth, the seriousness of middle life, the maturity of old age -- each bears some of Nature's fruit, which must be garnered in its own season.

[tr. Falconer (1923)]

The course of life is clear to see; nature has only one path, and it has no turnings. Each season of life has an advantage peculiarly its own; the innocence of children, the hot blood of youth, the gravity of the prime of life, and the mellowness of age all possess advantages that are theirs by nature, and that should be garnered each at its proper time.

[tr. Copley (1967)]

Life and nature have but one direction

Easy to take, without correction.

Each of life’s rite of passage dates

Has its own distinguishing traits:

A child’s weakness

A youth’s boldness

An adult’s authority

An old man’s maturity

And each with a certain natural zest

To be reaped when it’s time for its harvest.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

The course of life cannot change. Nature has but a single path and you travel it only once. Each stage of life has its own appropriate qualities -- weakness in childhood, boldness in youth, seriousness in middle age, and maturity in old age. These are fruits that must be harvested in due season.

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

You can be young without money but you can’t be old without it. You’ve got to be old with money because to be old without it is just too awful, you’ve got to be one or the other, either young or with money, you can’t be old and without it.

Tennessee Williams (1911-1983) American playwright

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Act 1 [Margaret] (1955)

(Source)

But what was it that delighted me save to love and to be loved? Still I did not keep the moderate way of the love of mind to mind — the bright path of friendship. Instead, the mists of passion steamed up out of the puddly concupiscence of the flesh, and the hot imagination of puberty, and they so obscured and overcast my heart that I was unable to distinguish pure affection from unholy desire. Both boiled confusedly within me, and dragged my unstable youth down over the cliffs of unchaste desires and plunged me into a gulf of infamy.

[Et quid erat quod me delectabat, nisi amare et amari? Sed non tenebatur modus ab animo usque ad animum quatenus est luminosus limes amicitiae, sed exhalabantur nebulae de limosa concupiscentia carnis et scatebra pubertatis, et obnubilabant atque obfuscabant cor meum, ut non discerneretur serenitas dilectionis a caligine libidinis. Utrumque in confuso aestuabat et rapiebat inbecillam aetatem per abrupta cupiditatum atque mersabat gurgite flagitiorum.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

Confessions, Book 2, ch. 2 / ¶ 2 (2.2.2) (c. AD 398) [tr. Outler (1955)]

(Source)

Agonizing over how horny he was at age 16.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

And what was it that I delighted in, but to love, and be loved? but I kept not the measure of love, of mind to mind, friendship's bright boundary: but out of the muddy concupiscence of the flesh, and the bubblings of youth, mists fumed up which beclouded and overcast my heart, that I could not discern the clear brightness of love from the fog of lustfulness. Both did confusedly boil in me, and hurried my unstayed youth over the precipice of unholy desires, and sunk me in a gulf of flagitiousnesses.

[tr. Pusey (1838)]

But what was it that I delighted in save to love and to be beloved? But I held it not in moderation, mind to mind, the bright path of friendship, but out of the dark concupiscence of the flesh, and the effervescence of youth exhalations came forth which obscured and overcast my heart, so that I was unable to discern pure affection from unholy desire. Both boiled confusedly within me, and dragged away my unstable youth into the rough places of unchaste desires, and plunged me into a gulf of infamy.

[tr. Pilkington (1876)]

And what was it that delighted me, but to love and to be loved? But the intercourse of mind with mind was not restricted within the clear bounds of honest love; but dense vapours arose from the miry lusts of the flesh, and the bubblings of youth, and clouded and darkened my heart; so that the clearness of true love could not be discerned from the thick mist of sensuality. Both boiled together confusedly within me, and carried away my weak young life over the precipices of passion, and merged me in a whirlpool of disgrace.

[tr. Hutchings (1890)]

Now what was it that gave me pleasure, save to love and to be loved? But I could not keep within the kingdom of light, where friendship binds soul to soul. From the quagmire of concupiscence, from the well of puberty, exhaled a mist which clouded and befogged my heart, so that I could not distinguish between the clear shining of affection and the darkness of lust. Both stormed confusedly within me, whirling my thoughtless youth over the precipices of desire, drowning it in the eddying pool of shame.

[tr. Bigg (1897)]

My one delight was to love and to be loved. But in this I did not keep the measure of mind to mind, which is the luminous line of friendship; but from the muddy concupiscence of the flesh and the hot imagination of puberty mists steamed up to becloud and darken my heart so that I could not distinguish the white light of love from the fog of lust. Both love and lust boiled within me, and swept my youthful immaturity over the precipice of evil desires to leave me half drowned in a whirlpool of abominable sins.

[tr. Sheed (1943)]

What was there to bring me delight except to love and be loved? But that due measure between soul and soul, wherein lie the bright boundaries of friendship, was not kept. Clouds arose from the slimy desires of the flesh and from youth’s seething spring. They clouded over and darkened my soul, so that I could not distinguish the calm light of chaste love from the fog of lust. Both kinds of affection burned confusedly within me and swept my feeble youth over the crags of desire and plunged me into a whirlpool of shameful deeds.

[tr. Ryan (1960)]

I cared for nothing but to love and be loved. But my love went beyond the affection of one mind for another, beyond the arc of the bright beam of friendship. Bodily desire, like a morass, and adolescent sex welling up within me exuded mists which clouded over and obscured my heart, so that I could not distinguish the clear light of true love from the murk of lust. Love and lust together seethed within me. In my tender youth they swept me away over the precipice of my body’s appetites and plunged me in the whirlpool of sin.

[tr. Pine-Coffin (1961)]