It is a rich, full-bodied whistle,

cracked ice crunching in pails,

the night that numbs the leaf,

the duel of two nightingales,

the sweet pea that has run wild,

Creation’s tears in shoulder blades.[Это – круто налившийся свист,

Это – щелканье сдавленных льдинок,

Это – ночь, леденящая лист,

Это – двух соловьев поединок.

Это – сладкий заглохший горох,

Это – слезы вселенной в лопатках.]Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) Russian poet, novelist, and literary translator

“Definition of Poetry [Определение поэзии],” ll. 1-6, My Sister — Life [сестра моя – жизнь] (1922)

(Source)

This is the translation, source unknown, given in Pasternak's obituary, "Farewell in a Poet's Land," Life Magazine (1960-06-13), and frequently quoted from there.

Alternate translations:

It's a tightly filled whistle,

it's the squeaking of jostled ice,

it's night, frosting the leaves,

it's two nightingales dueling.

It's the soundlessness of sweetpeas,

the tears of the universe in a pod.

[tr. Rudman/Boychuk (1983)]

It's a whistle that howls in the veins,

It's the crackle of ice under pressure,

It's the leaf-chilling night in the rain,

It's two nightingales dueling together.

It's the sweet pea all choked in the fields,

It's the universe weeping in pea pods.

[tr. Falen (2012)]

It’s a whistle, acutely full,

It’s a crackle of squeezed ice,

It’s night, freezing a leaf,

It’s two nightingales in a duel.

It’s the sweet grown-wildness of peas,

It’s tears of the universe in pods.

[tr. Livingstone (2015)]

It's a whistle blown ripe in a trice,

It's the cracking of ice in a gale,

It's a night that turns green leaves to ice,

It's a duel of two nightingales.

It is sweet-peas run gloriously wild,

It's the world's twinkling tears in the pod.

[Source]

Quotations about:

poetry

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Nothing so difficult as a beginning

In poesy, unless perhaps the end.

I sing of brooks, of blossoms, birds, and bowers:

Of April, May, of June, and July flowers.

I sing of Maypoles, Hock-carts, wassails, wakes,

Of bridegrooms, brides, and of their bridal cakes.

I write of youth, of love, and have access

By these to sing of cleanly wantonness;

I sing of dews, of rains, and piece by piece

Of balm, of oil, of spice and ambergris;

I sing of times trans-shifting, and I write

How roses first came red and lilies white;

I write of groves, of twilights, and I sing

The Court of Mab, and of the Fairy King;

I write of hell; I sing (and ever shall)

Of heaven, and hope to have it after all.

VERS LIBRE. A device for making poetry easier to write and harder to read.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

The Book of Burlesques, “The Jazz Webster” (1920)

(Source)

Known today as "Free Verse," and how most modern poetry is written.

Historical sense and poetic sense should not, in the end, be contradictory, for if poetry is the little myth we make, history is the big myth we live, and in our living, constantly remake.

Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989) American poet, novelist, literary critic

Brother to Dragons, Foreword (1953)

(Source)

There is no heroic poem in the world but is at bottom a biography, the life of a man; also, it may be said, there is no life of a man, faithfully recorded, but is a heroic poem of its sort, rhymed or unrhymed.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

“Sir Walter Scott,” London and Westminster Review No. 12 and 55, Art. 2 (1838-01)

(Source)

A review of Scott's Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Baronet, Vols. 1-6 (1837). Reprinted in Carlyle, Critical and Miscellaneous Essays (1827-1855).

The house of the bard Theodorus burned down!

What an insult, O Muses, to you!

The gods have done wrong:

For the credit of song

The bard — should have burned with it, too.

[Pierios vatis Theodori flamma penates

Abstulit. Hoc Musis et tibi, Phoebe, placet?

O scelus, o magnum facinus crimenque deorum,

Non arsit pariter quod domus et dominus!]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 11, epigram 93 (11.93) (AD 96) [tr. Nixon (1911), “An Oversight”]

(Source)

"On Theodorus, a Bad Poet." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Flames Theodore's Pierian roofs did seize.

Can this Apollo, this the Muses, please?

O oversight of the gods! O dire disaster!

To burn the harmless house, and spare the master!

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Poor poet Dogrel's house consum'd by fire?

Is the muse pleas'd? or father of the lyre?

O cruel Fate! what injury you do,

To burn the house! and not the master too!

[tr. Hay (1755), ep. 94]

The poor poet Theodore's goods, in a flame,

Gave you, wicked Muses, and Phebus full glee.

Ye sov'rain disposers, what sin and what shame,

That holder and house so disparted should be!

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 3, ep. 49]

Fitzgerald's house hath been on fire -- the Nine

All smiling saw that pleasant bonfire shine.

Yet -- cruel Gods! Oh! ill-contrived disaster!

The house is burnt -- the house -- without the Master!

[tr. Byron (c. 1820); referencing Irish/British poet, William Thomas Fitzgerald (1759-1829)]

The flames have destroyed the Pierian dwelling of the bard Theodorus. Is this agreeable to you, you muses, and you, Phoebus? Oh shame, oh great wrong and scandal of the gods, that house and householder were not burned together!

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

The poetic abode of bard Theodorus a fire has destroyed. Does this please you, ye Muses, and you, Phoebus? Oh, what guilt, oh, what a huge crime and scandal of the gods is here! House and master did! House and master did not burn together!

[tr. Ker (1919)]

A poet’s house consumed by fire!

Phoebus and ye, the heavenly choir,

What vengeance will ye now require

For such a fell disaster?

How foul a deed, how black a shame!

Can men acquit the gods of blame

When they delivered to the flame

The house and not its master?

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "The Gods' Mistake"]

Where were ye, Muses, when in angry flame

Sank Pye's Pierian dwelling? Phoebus, shame!

Oh cruel sin, o scandal to the sky,

To bake the Pye-dish and forget the Pye!

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), ep. 634; referring to Henry James Pye (1745-1813), Poet Laureate of the UK]

Not a single trace remains

Of poet Theodorus' home.

Everything completely burned,

Every last poetic tome!

You Muses and Apollo too,

Now are you fully satisfied?

O monstrous shame that when it burned

The poet was not trapped inside!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Flames have gutted th' abode Pierian

Of the wide-renowned poet Theodorus.

Didst thou permit this sacrilege, Apollo?

Where were ye, Muse's Chorus?

Ay me, I fondly sight, that was a crime,

A wicked deed, a miserable disaster.

Ye gods are much to blame: ye burnt the house

But failed to singe its master!

[tr. Wender (1980)]

Ted's studio burnt down, with all his poems.

Have the Muses hung their heads?

You bet, for it was criminal neglect

not also to have sautéed Ted.

[tr. Matthews (1992)]

Fire has consumed the Pierian home of poet Theodoras. Does this please the Muses and you, Phoebus? Oh crime, oh monstrous villainy and reproach to heaven! -- that house and householder did not perish together.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Flames took the home of poet Theodorus.

Are the Muses and Phoebus pleased with this disaster?

What a great crime and insult to the gods

not to have burned together home and master!

[tr. McLean (2014)]

BLANK-VERSE, n. Unrhymed iambic pentameters — the most difficult kind of English verse to write acceptably; a kind, therefore, much affected by those who cannot acceptably write any kind.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) American writer and journalist

“Blank-verse,” The Cynic’s Word Book (1906)

(Source)

Included in The Devil's Dictionary (1911). Originally published in the "Devil's Dictionary" column in the San Francisco Wasp (1881-05-14). In that version, it included the final sentence:

Of all English and American poets not a half-dozen have been able to write good blank-verse; and the six hundred Californian poets are not among them.

If there’s no money in poetry, neither is there poetry in money.

Robert Graves (1895-1985) English poet, novelist, critic

“Mammon,” lecture, London School of Economics and Political Science (1963-12-06)

(Source)

Reprinted in Mammon and the Black Goddess (1965).

Some thirty poems in the book

Are poor, you say. Egad!

If you’ve found thirty good ones, too,

The book is great, not bad.[‘Triginta toto mala sunt epigrammata libro.’

Si totidem bona sunt, Lause, bonus liber est.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 7, epigram 81 (7.81) (AD 92) [tr. Marcellino (1968)]

(Source)

"To Lausus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thou thirty epigrams dost note for bad:

Call my book good if thirty good it had.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

For thirty bad epigrams here you may look:

If as many good ones, it is a good book.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 12, ep. 7]

In this whole book there are thirty bad epigrams; if there as many good ones, Lausus, the book is good.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

"Take all your book, and there are thirty bad epigrams in it." If as many are good, Lausus, the book is a good one.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You’ve read my poems and condemn

Some thirty, so you say, of them:

The book’s a good one I submit,

If there are thirty good in it.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "Proportions"]

"There are thirty bad epigrams

in your book, at least."

If there are that many good ones,

Lausus, I'll be pleased.

[tr. Bovie (1970), mislabeled 7.18]

"There are thirty bad epigrams in the whole book." If there as many good ones, Lausus, it's a good book.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

"Your book as thirty epigrams unneeded."

I've only thirty clunkers? I've succeeded.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

"In this book, thirty poems are bad," you state.

Lausus, if thirty are good, the book is great.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

There is no such thing as a unique scientific vision, any more than there is a unique poetic vision. Science is a mosaic of partial and conflicting visions. But there is one common element in these visions. The common element is rebellion against the restrictions imposed by the locally prevailing culture, Western or Eastern as the case may be. It is no more Western than it is Arab or Indian or Japanese or Chinese. Arabs and Indians and Japanese and Chinese had a big share in the development of modern science. And two thousand years earlier, the beginnings of science were as much Babylonian and Egyptian as Greek. One of the central facts about science is that it pays no attention to East and West and North and South and black and yellow and white. It belongs to everybody who is willing to make the effort to learn it. And what is true of science is true of poetry. Poetry was not invented by Westerners. India has poetry older than Homer. Poetry runs as deep in Arab and Japanese culture as it does in Russian and English. Just because I quote poems in English, it does not follow that the vision of poetry has to be Western. Poetry and science are gifts given to all of humanity.

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) English-American theoretical physicist, mathematician, futurist

The Scientist as Rebel, Part 1, ch. 1 “The Scientist as Rebel” (2006)

(Source)

Originally given as a lecture in Cambridge, England (1992-11). Published as "The Scientist as Rebel," in John Cornwell, ed., Nature's Imagination, Introduction (1995), and "The Scientist as Rebel," New York Review of Books (1995-05-25).

It is true that the poet does not directly address his neighbors; but he does address a great congress of persons who dwell at the back of his mind, a congress of all those who have taught him and whom he has admired; that constitute his ideal audience and his better self. To this congress the poet speaks not of peculiar and personal things, but of what in himself is most common, most anonymous, most fundamental, most true of all men. And he speaks not in private grunts and mutterings but in the public language of the dictionary, of literary tradition, and of the street. Writing poetry is talking to oneself; yet it is a mode of talking to oneself in which the self disappears; and the product’s something that, though it may not be for everybody, is about everybody.

I, for example, do not like poems that resemble hay compressed into a geometrically perfect cube. I like it when the hay, unkempt, uncombed, with dry berries mixed in it, thrown together gaily and freely, bounces along atop some truck—and more, if there are some lovely and healthy lasses atop the hay—and better yet if the branches catch at the hay, and some of it tumbles to the road.

Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1933-2017) Russian poet, writer, film director, academic [Евге́ний Евтуше́нко, Evgenij Evtušenko]

“Yevtushenko: A Soviet Poet Turns to Movie Making,” New York Times (2 Feb 1986)

(Source)

I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

William Faulkner (1897-1962) American novelist

Speech, Nobel Banquet, Stockholm (1950-12-10)

(Source)

Faulkner received the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature.

His poetry seems to please the critics, and because it is plain-spoken, rhymes and scans, it pleases human beings as well.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

Familiar Poems Annotated, “Robert Frost, ‘Fire and Ice'” (1977)

(Source)

Once considered an art form that called for talent, or at least a craft that called for practice, a poem now needs only sincerity. Everyone, we’re assured, is a poet. Writing poetry is good for us. It expresses our inmost feelings, which is wholesome. Reading other people’s poems is pointless since those aren’t our own inmost feelings.

Barbara Holland (1933-2010) American author

Wasn’t the Grass Greener?: A Curmudgeon’s Fond Memories, “Poetry” (1999)

(Source)

To be a poet at twenty is to be twenty; to be a poet at forty is to be a poet.

[Écrire des vers à vingt ans, c’est avoir vingt ans. En écrire à quarante, c’est être poète.]

Eugène Delacroix (1799-1863) French painter [Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix]

(Attributed)

A review of English sources shows nearly all attributions of this quotation are to Delacroix, albeit without citation to where/when he said or wrote it.

There are some references attributing it to French poet Charles Péguy (1873-1914), e.g., Daniel Halevy's study of Péguy, Péguy and Les Cahiers de la Quinzaine, ch. 12, epigraph (1940) [tr. Bethell (1947)]), but even there, no actual citation is provided.

A few attributions can also be found to Canadian poet Louis Dudek (1918-2001).

A review of French sources show the quotation widely attributed to French author Francis Carco (1886-1958), but, again, I cannot find any actual citations of when or where Carco may have said or written that.

Vacerra likes no bards but those of old —

Only the poets dead are poets true!

Really, Vacerra — may I make so bold? —

It’s not worth dying to be liked by you.[Miraris veteres, Vacerra, solos

nec laudas nisi mortuos poetas.

Ignoscas petimus, Vacerra: tanti

non est, ut placeam tibi, perire.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 8, epigram 69 (8.69) (AD 94) [tr. Duff (1929)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:

Vacerra, thou approv'st of none

For Poets, but are dead and gone.

Pardon; for so much do not I

Esteeme thy praises as to dy.

[tr. May (1629)]

I ask’t thee oft, what Poets thou hast read,

And lik'st the best? Still thou reply'st, The dead.

I shall, ere long, with green turfs cover'd be;

Then sure thou't like, or thou wilt envie me.

[tr. Herrick (1648)]

The ancients all your veneration have:

You like no poet on this side of the grave.

Yet, pray, excuse me; if to pleases you, I

Can hardly think it worth my while to die.

[tr. Hay (1755)]

Vacerra! you admire only the ancients; your praise is restricted to the deceased poets. Pardon me, Vacerra, if I do not think your praise of so much value as to die for it.

[tr. Amos (1858)]

You admire, Vacerra, only the poets of old, and praise only those who are dead. Pardon me, I beseech you, Vacerra, it I think death too high a price to pay for your praise.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

The ancients only you admire, Vacerra;

No poet wins your favor till he dies.

I ask your pardon, but I don't think your praise

is worth so much that I will die for it.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

You admire, Vacerra, the ancients alone, and praise none but dead poets. Your pardon, pray, Vacerra: it is not worth my while, merely to please you, to die.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

You puff the poets of other days,

The living you deplore.

Spare me the accolade: your praise

Is not worth dying for.

[tr. Fitts (1967)]

Rigidly classical, you save

Your praise for poets in the grave.

Forgive me, it's not worth my while

Dying to earn your critical smile.

[tr. Michie (1972)]

You admire only the ancients, Vacerra, and praise no poets except dead ones. I crave your pardon, Vacerra; your good opinion is not worth dying for.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

There are poets you praise,

But I notice they’re all dead.

I’d rather find another way

to please you, friend, instead.

[tr. Matthews (1995)]

Vacerra, you admire the ancients only

and praise no poets but those here no more.

I beg that you will pardon me, Vacerra,

but pleasing you is not worth dying for.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Deceased authors thou admir'st alone,

And only praisest poets dead and gone:

Vacerra, pardon me, I will not buy

Thy praise so dear, as for the same to die.

[tr. Fuller]

You praise long-dead authors rapturously;

the living ones you savage or ignore,

but since your praise can’t grant immortality

I really don’t think it’s worth dying for.

[tr. Clark]

You pine for bards of old

and poets safely cold.

Excuse me for ignoring your advice,

but good reviews from you aren’t worth the price.

[tr. Juster]

Unless they’re dead, no poets seem

To fully satisfy;

Forgive me if, for some esteem,

I’m not prepared to die.

[tr. Mitchell]

More books have resulted from somebody’s need to write than from anybody’s need to read.

Ashleigh Brilliant (b. 1933) Anglo-American epigramist, aphorist, cartoonist

Pot-Shots, #3273

(Source)

If poetry is like an orgasm, an academic can be likened to someone who studies the passion-stains on the bedsheets.

Irving Layton (1912-2006) Romanian-Canadian poet [b. Israel Pincu Lazarovitch]

“Obs II,” The Whole Bloody Bird (1969)

(Source)

Histories make men wise; poets, witty; the mathematics, subtle; natural philosophy, deep; moral, grave; logic and rhetoric, able to contend.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

“Of Studies,” Essays, No. 50 (1625)

(Source)

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away,

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing poetry.Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) American poet

“There is no Frigate like a Book,” ll. 1-4 (c. 1873)

(Source)

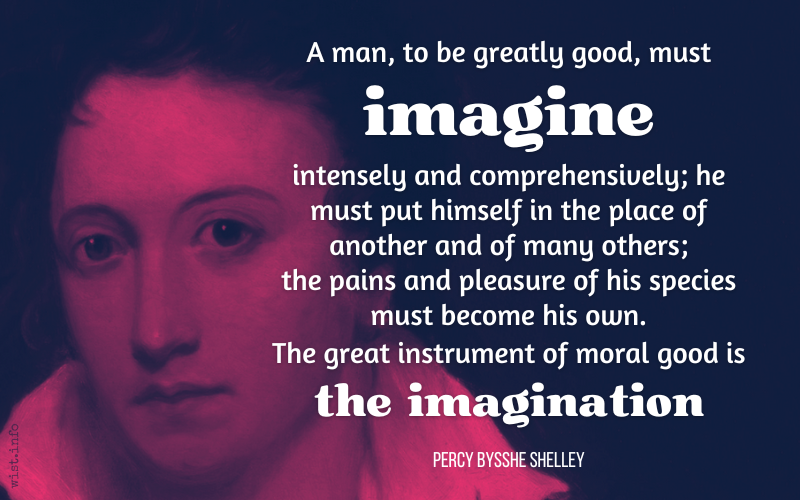

A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasure of his species must become his own. The great instrument of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect by acting upon the cause.

I am very sure that any man of common understanding may, by proper culture, care, attention and labor, make himself whatever he pleases, except a great poet.

Lord Chesterfield (1694-1773) English statesman, wit [Philip Dormer Stanhope]

Letter to his son, #113 (9 Oct 1746)

(Source)

We may have an excellent Ear in Musick, without being able to perform in any kind. We may judge well of Poetry, without being Poets, or possessing the least of a Poetick Vein: But we can have no tolerable Notion of Goodness, without being tolerably good.

The Muse was suddenly there for Dad.

The Truth lay easy in his mind.

The Subconscious lay saying its say, untouched, and flowing off his tongue.

As we must learn to do in our writing.

As we can learn from every man or woman or child around us when, touched and moved, they tell of something they loved or hated this day, yesterday, or some other day long past. At a given moment, the fuse, after sputtering wetly, flares and the fireworks begin.

Oh, it’s limping crude hard work for many, with language in their way. But I have heard farmers tell about their very first wheat crop on their first farm after moving from another state, and if it wasn’t Robert Frost talking, it was his cousin, five times removed. I have heard locomotive engineers talk about America in the tones of Thomas Wolfe who rode our country with his style as they ride it in their steel. I have heard mothers tell of the long night with their firstborn when they were afraid that they and the baby might die. And I have heard my grandmother speak of her first ball when she was seventeen. And they were all, when their souls grew warm, poets.Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) American writer, futurist, fabulist

“How to Keep and Feed a Muse,” The Writer (1961-07)

(Source)

Reprinted in Bradbury, Zen in the Art of Writing (1990).

With a view to poetry, an impossible thing that is believable is preferable to an unbelievable thing that is possible.

[πρός τε γὰρ τὴν ποίησιν αἱρετώτερον πιθανὸν ἀδύνατον ἢ ἀπίθανον καὶ δυνατόν.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Poetics [Περὶ ποιητικῆς, De Poetica], ch. 24 / 1461b.11 (c. 335 BC) [tr. Sachs (2006)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

- "The poet should prefer probable impossibilities to improbable possibilities." [tr. Butcher (1895)]

- "A likely impossibility is always preferable to an unconvincing possibility." [tr. Bywater (1909)]

- "You should prefer a plausible impossibility to an unconvincing possibility." [tr. Margoliouth (1911)]

- "For poetic effect a convincing impossibility is preferable to that which is unconvincing though possible." [tr. Fyfe (1932)]

- "Probable impossibilities are preferable to implausible possibilities." [tr. Halliwell (1986)]

- "In relation to the needs of the composition, a believable impossibility is preferable to an unbelievable possibility." [tr. Janko (1987)]

- "With respect to the requirement of art, the probable impossible is always preferable to the improbable possible."

- "For the purposes of poetry a convincing impossibility is preferable to an unconvincing possibility."

Poetry demands a man with special gift for it, or else one with a touch of madness in him; the former can easily assume the required mood, and the latter may be actually beside himself with emotion.

[διὸ εὐφυοῦς ἡ ποιητική ἐστιν ἢ μανικοῦ: τούτων γὰρ οἱ μὲν εὔπλαστοι οἱ δὲ ἐκστατικοί εἰσιν.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Poetics [Περὶ ποιητικῆς, De Poetica], ch. 17 / 1455a.33 (c. 335 BC) [tr. Bywater (1909)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Fyfe (below) notes μανικός to mean "genius to madness near allied," and adds "Plato held that the only excuse for a poet was that he couldn't help it." A possible source of Seneca's "touch of madness" attribution to Aristotle. Alternate translations:

Poetry implies either a happy gift of nature or a strain of madness. In the one case a man can take the mould of any character; in the other, he is lifted out of his proper self.

[tr. Butcher (1895)]

Poetry is the work for the finely constituted or the hysterical; for the hysterical are impressionable, whereas the finely constituted are liable to outbursts.

[tr. Margoliouth (1911); whiles this seems backward, Margoliouth further explains in his footnote.]

Poetry needs either a sympathetic nature or a madman, the former being impressionable and the latter inspired.

[tr. Fyfe (1932)]

Hence the poetic art belongs either to a naturally gifted person or an insane one, since those of the former sort are easily adaptable and the latter are out of their senses.

[tr. Sachs (2006)]

In order to write tragic poetry, you must be either a genius who can adapt himself to anything, or a madman who lets himself get carried away.

[tr. Kenny (2013)]

Poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history; poetry utters universal truths, history particular statements.

[διὸ καὶ φιλοσοφώτερον καὶ σπουδαιότερον ποίησις ἱστορίας ἐστίν: ἡ μὲν γὰρ ποίησις μᾶλλον τὰ καθόλου, ἡ δ᾽ ἱστορία τὰ καθ᾽ ἕκαστον λέγει.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Poetics [Περὶ ποιητικῆς, De Poetica], ch. 9 / 1451b.5 (c. 335 BC) [tr. Kenny (2013)]

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

Poetry, therefore, is a more philosophical and a higher thing than history: for poetry tends to express the universal, history the particular.

[tr. Butcher (1895)]

Poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars.

[tr. Bywater (1909)]

Poetry is the more scientific and the higher class; for it generalizes rather, whereas history particularizes.

[tr. Margoliouth (1911)]

Poetry is something more scientific and serious than history, because poetry tends to give general truths while history gives particular facts.

[tr. Fyfe (1932)]

Poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history; in fact, poetry speaks more of universals, whereas history of particulars.

[tr. Halliwell (1986)]

Poetry is a more philosophical and more serious thing than history: poetry tends to speak of universals, history of particulars.

[tr. Janko (1987), sec. 3.2.3]

Poetry is more philosophical and more serious than history; poetry tends to speak of universals, history of particulars.

[tr. Janko (1987), sec. 3.2.3]

Poetry is more speculative and more serious business than history: for poetry deals more with universals, history with particulars.

[tr. Whalley (1997)]

Poetry is a more philosophical and more serious thing than history, since poetry speaks more of things that are universal, and history of things that are particular.

[tr. Sachs (2006)]

Poetry is finer and more philosophical than history; for poetry expresses the universal, and history only the particular.

[tr. Unknown]

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.

Robert Frost (1874-1963) American poet

“The Figure a Poem Makes,” Collected Poems, Preface, “The Figure a Poem Makes” (1939)

(Source)

KEATING: We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.