However that may be, it is always disastrous when governments set to work to uphold opinions for their utility rather than for their truth. As soon as this is done it becomes necessary to have a censorship to suppress adverse arguments, and it is thought wise to discourage thinking among the young for fear of encouraging “dangerous thoughts.” When such mal-practices are employed against religion as they are in Soviet Russia, the theologians can see that they are bad, but they are still bad when employed in defence of what the theologians think good. Freedom of thought and the habit of giving weight to evidence are matters of far greater moral import than the belief in this or that theological dogma. On all these grounds it cannot be maintained that theological beliefs should be upheld for their usefulness without regard to their truth.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

“Is There a God?” (1952)

(Source)

Essay commissioned by Illustrated magazine in 1952, but never published there. First publication in Russell, Last Philosophical Testament, 1943-68 (1997) [ed. Slater/Köllner].

Quotations about:

morality

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

And what is shameful if those who do it don’t think it so?

[τί δ’ αἰσχρὸν ἢν μὴ τοῖσι χρωμένοις δοκῇ]

Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Æolus [Αἴολος], frag. 19 (TGF) [tr. Aleator (2012)]

(Source)

This bit of moral relativism (likely coming from Macareus, the son of Aeolus, who committed incest with his sister, Canace) continues to provoke commentary, thus varied translations. Aristophanes includes a reference to this line in his The Frogs.

Nauck frag. 19, Barnes frag. 5, Musgrave frag. 1. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:

But what is base, if it appear not base

To those who practice what their soul approves?

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]

What is shameful, if it does not seem to be so to those who do it?

[Source]

What's wrong if they who do it think not so?

[Source (1902)]

Why shameful, if it does not seem so to those who practice it?

[Source (2018)]

To an embalmer there are no good men and bad men. There are only dead men and live men.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

A Little Book in C Major, ch. 4, § 15 (1916)

(Source)

Call me a scoundrel, only call me rich!

All ask how great my riches are, but none

Whether my soul is good.[ἔα με κερδαίνοντα κεκλῆσθαι κακόν]

Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bellerophon [Βελλεροφῶν], frag. 181 (Nauck, TGF) (c. 430 BC) [tr. Gummere (1925)]

(Source)

Barnes frag. 65. Found (in Latin) in Seneca, Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, 115.14:

Sine me vocari pessimum, ut dives vocer.

An dives, omnes quaerimus, nemo, an bonus.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:

If any gain ensue, I am content.

To be term'd wicked. We all ask this question,

Whether a man be rich, not whether virtuous.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]

Let me be called a scoundrel, but a rich one.

We all ask if he’s rich, not if he’s good.

[Source]

LEAR: I am a man

More sinned against than sinning.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

King Lear, Act 3, sc. 2, l. 62ff (3.2.62-63) (1606)

(Source)

I’m an atheist, and that’s it. I believe there’s nothing we can know except that we should be kind to each other and do what we can for other people.

Katharine Hepburn (1907-2003) American actress

“Kate Talks Straight,” interview by Myrna Blyth, Ladies’ Home Journal (1991-10)

(Source)

I am afraid that the pleasantness of an employment does not always evince its propriety.

History. We want to find moral lessons in it, but its only lessons are of politics, military art, etc.

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], 1806 [tr. Auster (1983)]

(Source)

I have been unable to find an analog in other translations, or in the original French.

Imaginary evil is romantic and varied; real evil is gloomy, monotonous, barren, boring. Imaginary good is boring; real good is always new, marvelous, intoxicating.

Simone Weil (1909-1943) French philosopher

Gravity and Grace [La Pesanteur et la Grâce], “Evil” (1947) [ed. Thibon] [tr. Crawford/von der Ruhr (1952)]

(Source)

Speaking of the portrayal of good and evil in literature.

Boundless compassion for all living things is the firmest and surest guarantee of pure moral conduct, and needs no casuistry. Whoever is inspired with it will assuredly injure no one, will wrong no one, will encroach on no one’s rights; on the contrary, he will be lenient and patient with everyone, will forgive everyone, will help everyone as much as he can, and all his actions will bear the stamp of justice, philanthropy, and loving-kindness. On the other hand, if we attempt to say, “This man is virtuous but knows no compassion,” or “He is an unjust and malicious man yet he is very compassionate,” the contradiction is obvious.

[Denn gränzenloses Mitleid mit allen lebenden Wesen ist der festeste und sicherste Bürge für das sittliche Wohlverhalten und bedarf keiner Kasuistik. Wer davon erfüllt ist, wird zuverlässig Keinen verletzen, Keinen beeinträchtigen, Keinem wehe thun, vielmehr mit Jedem Nachsicht haben, Jedem verzeihen, Jedem helfen, so viel er vermag, und alle seine Handlungen werden das Gepräge der Gerechtigkeit und Menschenliebe tragen. Hingegen versuche man ein Mal zu sagen: „dieser Mensch ist tugendhaft, aber er kennt kein Mitleid.” oder: „es ist ein ungerechter und boshafter Mensch; jedod, ist er sehr mitleidig;” so wird der Widerspruch fühlbar.]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

On the Basis of Morality [Über die Grundlage der Moral], § 19.4 (Part 3, ch. 8.4) (1840) [tr. Saunders (1965)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:

Boundless compassion for all living beings is the surest and most certain guarantee of pure moral conduct, and needs no casuistry. Whoever is filled with it will assuredly injure no one, do harm to no one, encroach on no man's rights ; he will rather have regard for every one, forgive every one, help every one as far as he can, and all his actions will bear the stamp of justice and loving-kindness. On the other hand, if we try to say: "This man is virtuous, but he is a stranger to Compassion"; or: "he is an unjust and malicious man, yet very compassionate;" the contradiction at once leaps to light.

[tr. Bullock (1903)]

Conscience is a man’s compass, and though the needle sometimes deviates, though one often perceives irregularities in directing one’s course after it, still one must try to follow its direction.

The delight of social relations between friends is fostered by a shared attitude to life, together with certain differences of opinion on intellectual matters, through which either one is confirmed in one’s own views, or else one gains practice and instruction through argument.

[Le plaisir de la société entre les amis se cultive par une ressemblance de goût sur ce qui regarde les moeurs, et par quelques différences d’opinions sur les sciences: par là ou l’on s’affermit dans ses sentiments, ou l’on s’exerce et l’on s’instruit par la dispute.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 5 “Of Society and Conversation [De la Société et de la Conversation],” § 61 (5.61) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

The pleasure of Society amongst Friends is cultivated by a likeness of Inclinations, as to Manners; and a difference in Opinion, as to Sciences: the one confirms and humours us in our sentiments; the other exercises and instructs us by disputation.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]

The Pleasure of Society amongst Friends, is cultivated by a likeness of Inclinations, as to Manners, and by some difference in Opinion, as to Sciences: The one confirms us in our Sentiments, the other exercises and instructs us by Disputation.

[Curll ed. (1713)]

The pleasure of social intercourse amongst friends is kept up by a similarity of morals and manners, and by slender differences in opinion about science; this confirms us in our sentiments, exercises our faculties or instructs us through arguments.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

Moral compromises don’t stop happening even when everyone involved is trying to do the right thing.

Elizabeth Bear (b. 1971) American author [pseud. for Sarah Bear Elizabeth Wishnevsky]

Ancestral Night (2009)

(Source)

Evil communication corrupts good manners. I hope to live to hear that good communication corrects “bad manners.”

Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806) American naturalist, surveyor, almanac author, mathematician

Handwritten note in one of his almanacs

(Source)

Quoted in Friends' Intelligencer, vol. 11 (1854).

Manners consist in pretending that we think as well of others as of ourselves. Manners are necessary because, as a rule, there is a pretence; when our good opinion of others is genuine, manners look after themselves. Perhaps instead of teaching manners, parents should teach the statistical probability that the person you are speaking to is just as good as you are. It is difficult to believe this; very few of us do, in our instincts, believe it. One’s own ego seems so incomparably more sensitive, more perceptive, wiser and more profound than other people’s. Yet there must be very few of whom this is true, and it is not likely that oneself is one of those few. There is nothing like viewing oneself statistically as a means both to good manners and to good morals.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

“On Being Insulting,” New York American (1934-12-21)

(Source)

We cannot, by total reliance on law, escape the duty to judge right and wrong [….] There are good laws and there are occasionally bad laws, and it conforms to the highest traditions of a free society to offer resistance to bad laws, and to disobey them.

Alexander M. Bickel (1924-1974) Romanian-American law professor, constitutional scholar

Politics and the Warren Court, Part 3, ch. 5 “Civil Rights and Civil Disobedience” (1965)

(Source)

There is no outward mark of politeness that does not have a profound moral reason. The right education would be that which taught the outward mark and the moral reason together.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) German poet, statesman, scientist

Elective Affinities, Part 2, ch. 5 (1809) [tr. Hollingdale (1971)]

(Source)

Alternate translation:

There is no outward sign of courtesy that does not rest on a deep moral foundation. . The proper education would be that which communicated the sign and the foundation of it at the same time.

[Niles ed. (1872)]

You’re going to have to explain the logic of man to me, Mr. Grudge. For example, tell me how you come about your selective morality. This ease with which you strip off your conscience like an overcoat — and let your satisfied belch drown out the hunger cries that fill the air around you. How do you create the exact science whereby you disinvolve yourself from all the anguish of the world that doesn’t happen to be in your direct line of vision? That doesn’t take a special breed of man at all, Mr. Grudge. That is man in his normal condition.

Rod Serling (1924-1975) American screenwriter, playwright, television producer, narrator

A Carol for Another Christmas [Ghost of Christmas Present] (1964)

(Source)

A good cause can become bad if we fight for it with means that are indiscriminately murderous. A bad cause can become good if enough people fight for it in a spirit of comradeship and self-sacrifice. In the end it is how you fight, as much as why you fight, that makes your cause good or bad.

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) English-American theoretical physicist, mathematician, futurist

Disturbing the Universe, ch. 4 (1979)

(Source)

The gentleman admires rightness above all. A gentleman who possessed courage but lacked a sense of rightness would create political disorder, while a common person who possessed courage but lacked a sense of rightness would become a bandit.

[君子義以爲上、君子有勇而無義、爲亂、小人有勇而無義、爲盜]

[君子义以为上君子有勇而无义为乱小人有勇而无义为盗]Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 17, verse 23 (17.23) (6th C. BC – AD 3rd C.) [tr. Slingerland (2003)]

(Source)

When asked if a gentleman (junzi) values valor. Annping Chin's notes suggest that the two uses of junzi are different: the first, speaking in general of a moral person, the second of a person of high status (vs the person of low status, xiaoren) following).

(Source (Chinese) 1, 2). Alternate translations:

The superior man holds righteousness to be of highest importance. A man in a superior situation, having valour without righteousness, will be guilty of insubordination; one of the lower people having valour without righteousness, will commit robbery.

[tr. Legge (1861)]

Righteousness he counts higher. A gentleman who is brave without being just may become turbulent; while a common person who is brave and not just may end in becoming a highwayman.

[tr. Jennings (1895)]

A gentleman esteems what is right as of the highest importance. A gentleman who has valour, but is without a knowledge and love of what is right, is likely to commit a crime. A man of the people who has courage, but is without the knowledge and love of what is right, is likely to become a robber.

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898)]

Men of the superior class deem rectitude the highest thing. It is men of the superior class, with courage but without rectitude, who rebel. It is men of the lower class, with courage but without rectitude, who become robbers.

[tr. Soothill (1910)]

The proper man puts equity at the top, if a gentleman have courage without equity it will make a mess; if a mean man have courage without equity he will steal.

[tr. Pound (1933)]

A gentleman gives the first place to Right. If a gentleman has courage but neglects Right, he becomes turbulent. If a small man has courage but neglects Right, he becomes a thief.

[tr. Waley (1938)]

The perfect gentleman is given to justice and assigns to it first place. If the perfect gentleman possesses courage but not justice, there will be disorders. In the case of the mean man, there will be burglaries.

[tr. Ware (1950), 17.21]

For the gentleman it is morality that is supreme. Possessed of courage but devoid of morality, a gentleman will make trouble while a small man will be a brigand.

[tr. Lau (1979)]

Rightness the gentleman regards as paramount; for if a gentleman has courage but lacks a sense of right and wrong, he will cause political chaos; and if a small man has courage but lacks a sense of right and wrong, he will commit burglary.

[tr. Dawson (1993), 17.21]

A gentleman puts justice above everything. A gentleman who is brave but not just may become a rebel; a vulgar man who is brave but not just may become a bandit.

[tr. Leys (1997)]

The gentleman regards righteousness as supreme. A gentleman who possesses courage but wants righteousness will become rebel; a small man who possesses courage but wants righteousness will become a bandit. [tr. Huang (1997), 17.22]A gentleman stresses the righteousness as a top rule. If a gentleman has the braveness but no righteousness, will be disordered. If a mean person has the braveness but no righteousness, will be a robber.

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998), No. 463]

In fact, the exemplary person gives first priority to appropriate conduct (yi). An exemplary person who is bold yet is lacking a sense of appropriateness will be unruly, while a petty person of the same cut will be a thief.

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]

With the gentleman, right comes before all else. If a gentleman has courage but lacks a sense of right, he will make a rebellion. If a little man has courage but lacks a sense of right, he will become a thief.

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998), 17:21]

The noble-minded honor Duty above all. In the noble-minded, courage without Duty leads to turmoil. In little people, courage without Duty leads to theft and robbery.

[tr. Hinton (1998), 17.22]

The gentleman holds rightness in highest esteem. A gentleman who possesses courage but lacks rightness will become rebellious. A petty man who possesses courage but lacks rightness will turn to thievery.

[tr. Watson (2007)]

The gentleman (junzi) puts rightness at the top. If a man of high status (junzi) has courage but not a sense of rightness, he will create political upheaval. If a lowly man has courage but not a sense of rightness, he will turn to banditry.

[tr. Annping Chin (2014)]

A Jun Zi's top objective is righteousness. If a Jun Zi has valor but acts against righteousness, he is prone to make trouble. If a Xiao Ren has valor but acts against righteousness, he is prone to commit crimes.

[tr. Li (2020)]

But a man can be physically courageous and morally craven.

Melvin B. Tolson (1898-1966) American poet, educator, columnist, politician

“Paul Robeson Rebels against Hollywood’s Dollars,” Caviar and Cabbage column, Washington Tribune (25 Mar 1939)

(Source)

We cannot learn what causes violence and how we could prevent it as long as we are thinking in the traditional moral and legal terms. The only questions that this way of thinking can ask take the form: “How evil (or heroic) was this particular act of violence, and how much punishment (or reward) does the person who did it deserve?” But even if it were possible to gain the knowledge that would be necessary to answer those questions (which it is not), answers would still not help us in the least to understand what causes violence or how we could prevent it — these are empirical not moral questions.

James Gilligan (b. c. 1936) American psychiatrist and author

Preventing Violence, Introduction (2001)

(Source)

In pursuit of virtue, do not be afraid to overtake your teacher.

[當仁、不讓於師。]

[当仁不让于师]Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 15, verse 36 (15.36) (6th C. BC – 3rd C. AD) [tr. Leys (1997)]

(Source)

(Source (Chinese) 1, 2). Modern numbering is 15.36; exceptions (mostly after Legge) noted below. Alternate translations:

Let every man consider virtue as what devolves on himself. He may not yield the performance of it even to his teacher.

[tr. Legge (1861), 15.35]

Rely upon good-nature. 'Twill not allow precedence (even) to a teacher.

[tr. Jennings (1895), 15.35]

When the question is one of morality, a man need not defer to his teacher.

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898), 15.35]

He upon whom a Moral duty devolves should not give way even to his Master.

[tr. Soothill (1910), 15.35]

He who has undertaken the way of Virtue does not yield place to his Teacher.

[tr. Soothill (1910), 15.35, alternate]

Manhood’s one's own, not leavable to teacher.

[tr. Pound (1933), 15.35]

When it comes to Goodness one need not avoid competing with one's teacher.

[tr. Waley (1938), 15.35]

He who is manhood at its best does not make way for the teacher.

[tr. Ware (1950)]

When faced with the opportunity to practice benevolence do not give precedence even to your teacher.

[tr. Lau (1979)]

When one is confronted by humaneness, one does not yield precedence to one's teacher.

[tr. Dawson (1993)]

Confronting an act of humanity, do not yield the precedence even to your teacher.

[tr. Huang (1997)]

One should not decline modestly to one's teacher when one faces the benevolent thing.

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998), # 420]

In striving to be authoritative in your conduct (ren), do not yield even to your teacher.

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]

With (ren), one need not defer to one's teacher.

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998)]

Abide in Humanity, and you need not defer to any teacher.

[tr. Hinton (1998)]

When it comes to being Good, defer to no one, not even your teacher.

[tr. Slingerland (2003)]

In matters of humaneness, do not defer even to your teacher.

[tr. Watson (2007)]

When encountering matters that involve the question of humaneness, do not yield even to your teacher.

[tr. Annping Chin (2014)]

When confronted with a challenge of upholding Ren virtue or not, one should not yield -- not even to his own teacher.

[tr. Li (2020), 15.37]

The superior man in everything considers righteousness to be essential. He performs it according to the rules of propriety. He brings it forth in humility. He completes it with sincerity. This is indeed a superior man.

[君子義以為質,禮以行之,孫以出之,信以成之,君子哉]

Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 15, verse 18 (15.18) (6th C. BC – 3rd C. AD) [tr. Legge (1861), 15.17]

(Source)

(Source (Chinese)). Alternate translations, noting where Legge's numbering is used:

When the "superior man" regards righteousness as the thing material, gives operation to it according to the rules of propriety, lets it issue in humility, and become complete in sincerity, -- there indeed is your superior man!

[tr. Jennings (1895), 15.17]

A wise and good man makes Right the substance of his being; he cries it out with judgment and good sense; he speaks it with modesty; and he attains it with sincerity: -- such a man is a really good and wise man!

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898), 15.17]

The noble man takes the Right as his foundation principle, reduces it to practice with all courtesy, carries it out with modesty, and renders it perfect with sincerity, -- such is the noble man.

[tr. Soothill (1910), 15.17]

When a princely man makes the Right his fundamental principle, makes Courtesy his rule in evolving it, Modesty his rule for exhibiting it, and Sincerity his rule for effectuating it perfectly, -- what a princely man he is!

[tr. Soothill (1910), 15.17, alternate]

The proper man gives substance to his acts by equity. He proceeds according to the rites, puts them forth modestly, and makes them perfect by sticking to his word. That's the proper man (in whom's the voice of his forebears).

[tr. Pound (1933), 15.17]

The gentleman who takes the right as his material to work upon and ritual as the guide in putting what is right into practice, who is modest in setting out his projects and faithful in carrying them to their conclusions, he indeed is a true gentleman.

[tr. Waley (1938), 15.17]

He whose very substance is justice; whose actions are governed by the rites; whose participation in affairs is compliant; and whose crowning perfection is truthfulness -- that man is a perfect gentleman.

[tr. Ware (1950)]

The gentleman has morality as his basic stuff and by observing the rites puts it into practice, by being modest gives it expression, and by being trustworthy in word brings it to completion. Such is a gentleman indeed!

[tr. Lau (1979)]

Righteousness the gentleman regards as the essential stuff and the rites are his means of putting it into effect. If modesty is the quality with which he reveals it and good faith is his method of bringing it to completion, he is indeed a gentleman.

[tr. Dawson (1993)]

A gentleman takes justice as his basis, enacts it in conformity with the ritual, expounds it with modesty, and through good faith, brings it to fruition. That is how a gentleman proceeds.

[tr. Leys (1997)]

A gentleman considers righteousness his major principle; he practices it in accordance with the rituals, utters it in modest terms, and fulfils it with truthfulness. A gentleman indeed!

[tr. Huang (1997)]

A gentleman takes the righteousness as his essence, practices with the rituals, words with modesty, and gets achievement with honesty. It is the gentleman.

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998), v. 402]

Having a sense of appropriate conduct [yi] as one's basic disposition [zhi], developing it in observing ritual propriety [li], expressing it with modesty, and consummating it in making good on one's word [xin]; this then is an exemplary person [junzi].

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]

If a gentleman has right as his substance, and puts it in practice with propriety, promulgates it with lineality, and brings it to a conclusion with fidelity, he is a gentleman indeed!

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998), LY17 c0270 addition]

The noble-minded make Duty their very nature. They put it into practice through Ritual; they make it shine through humility; and standing by their words, they perfect it. Then they are noble-minded indeed!

[tr. Hinton (1998)]

The gentleman takes rightness as his substance, puts it into practice by means of ritual, gives it expression through modesty, and perfects it by being trustworthy. Now that is a gentleman!

[tr. Slingerland (2003)]

The gentleman makes rightness the substance, practices it through ritual, displays it with humility, brings it to completion with trustworthiness. That’s the gentleman.

[tr. Watson (2007)]

The gentleman makes rightness the substance. He works at it through ritual propriety; he expresses it with modesty; he brings it to completion by being trustworthy. Now that is a gentleman!

[tr. Annping Chin (2014)]

A Jun Zi regards righteousness and honor as fundamental bases, acts in line with Li, shows humility, delivers promises, and completes contracts with sincerity and trust. If so, he is indeed a Jun Zi.

[tr. Li (2020)]

A leader takes rightness as their essence, puts it into practice through ritual, manifests it through humility, and brings it to fruition through trustworthiness. This is how a leader behaves.

[tr. Brown (2021)]

Holden decided that he was okay with not feeling any remorse for them. The moral complexity of the situation had grown past his ability to process it, so he just relaxed in the warm glow of victory instead.

Daniel Abraham (b. 1969) American writer [pseud. James S. A. Corey (with Ty Franck), M. L. N. Hanover]

Leviathan Wakes, ch. 41 (2011) [with Ty Franck]

(Source)

Cherish what you believe. Don’t job off one single value judgment because it swims upstream against what appears to be a majority. Respect your own logic, your own sense of morality. Death and taxes may be the only absolutes. It’s for you to conjure up the modus operandi of how you live, act, react and hammer out a code of ethics. Certainly listen to arguments; certainly ponder and respect the opinions of your peers. But there’s a point you compromise, and there’s a point all human beings draw a line and say, “Beyond this point it’s not right or just or honest, and beyond this point I don’t move.”

Rod Serling (1924-1975) American screenwriter, playwright, television producer, narrator

Commencement Address, Ithaca College, New York (13 May 1972)

(Source)

“There’s a right thing to do,” Holden said.

“You don’t have a right thing, friend,” Miller said. “You’ve got a whole plateful of maybe a little less wrong.”

Daniel Abraham (b. 1969) American writer [pseud. James S. A. Corey (with Ty Franck), M. L. N. Hanover]

Leviathan Wakes, ch. 36 (2011) [with Ty Franck]

(Source)

Courage is the ladder on which all the other virtues mount.

Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987) American dramatist, diplomat, politician

“Is the New Morality Destroying America?”, speech, IBM Golden Circle Conference, Honolulu (28 May 1978)

(Source)

The speech was first published in The Human Life Review, Vol. 4 (1978). Then the quotation was extracted in "Quotable Quotes," Reader's Digest (May 1979), which is the most common citation.

More discussion about this quotation: The Big Apple: “Courage is the ladder on which all the other virtues mount”.

Acts and their consequences are the things by which our fellows judge us. Anything else, and all that you get is a cheap feeling of moral superiority by thinking how you would have done something nicer if it had been you. So as for the rest, leave it to heaven. I’m not qualified.

Count heads. That is what matters in all things. When you must, follow the common taste, and make your way toward eminence. The wise should adapt themselves to the present, even when the past seems more attractive, both in the clothes of the soul and of the body. This rule for living holds for everything but goodness, for one must always practice virtue.

[El gusto de las cabeças haze voto en cada orden de cosas. Ésse se ha de seguir por entonces, y adelantar a eminencia. Acomódese el cuerdo a lo presente, aunque le parezca mejor lo pasado, así en los arreos del alma como del cuerpo. Sólo en la bondad no vale esta regla de vivir, que siempre se ha de practicar la virtud.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 120 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:

Let a prudent man accommodate himself to the present, whether as to body, or mind, though the past may even seem better unto him. In manners onely that rule is not to be observed, seeing vertue is at all times to be practised.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]

In everything the taste of the many carries the votes; for the time being one must follow it in the hope of leading it to higher things. In the adornment of the body as of the mind adapt yourself to the present, even though the past appear better. But this rule does not apply to kindness, for goodness is for all time.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]

The choice of the many carries the vote in every field. For the time being, therefore, it must be bowed to, in order to bring it to higher level: the man of wisdom accommodates himself to the present, even though the past seems better, alike in the dress of his spirit, as in the dress of his body. Only in the matter of being decent does this rule of life not apply, for virtue should be practiced eternally.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

True character arises from a deeper well than religion. It is the internalization of moral principles of a society, augmented by those tenets personally chosen by the individual, strong enough to endure through trials of solitude and adversity. The principles are fitted together into what we call integrity, literally the integrated self, wherein personal decisions feel good and true. Character is in turn the enduring source of virtue. It stands by itself and excites admiration in others. It is not obedience to authority, and while it is often consistent with and reinforced by religious belief, it is not piety.

E. O. Wilson (1929-2021) American biologist, naturalist, writer [Edward Osborne Wilson]

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, ch. 11 “Ethics and Religion” (1998)

(Source)

The problem of drugs, of divorce, of race prejudice, of unmarried pregnancy, and so on — as if evil were a problem, something that an be solved, that has an answer, like a problem in fifth grade arithmetic. If you want the answer, you just look in the back of the book. That is escapism, that posing evil as a “problem,” instead of what it is: all the pain and suffering and waste and loss and injustice we will meet our loves long, and must face and cope with over and over and over, and admit, and live with, in order to live human lives at all.

Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) American writer

“The Child and the Shadow,” Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress (Apr 1975)

(Source)

On the difficulty of "realistic fiction" for children to teach morality. First delivered as a speech; later reprinted in The Language of the Night (1979).

There is always a certain glamour about the idea of a nation rising up to crush an evil simply because it is wrong. Unfortunately, this can seldom be realized in real life; for the very existence of the evil usually argues a moral weakness in the very place where extraordinary moral strength is called for.

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) American writer, historian, social reformer [William Edward Burghardt Du Bois]

The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, ch. 12, sec. 93 (1896)

(Source)

In a word, our moral dispositions are formed as a result of the corresponding activities. Hence it is incumbent on us to control the character of our activities, since on the quality of these depends the quality of our dispositions. It is therefore not of small moment whether we are trained from childhood in one set of habits or another; on the contrary it is of very great, or rather of supreme, importance.

[καὶ ἑνὶ δὴ λόγῳ ἐκ τῶν ὁμοίων ἐνεργειῶν αἱ ἕξεις γίνονται. διὸ δεῖ τὰς ἐνεργείας ποιὰς ἀποδιδόναι: κατὰ γὰρ τὰς τούτων διαφορὰς ἀκολουθοῦσιν αἱ ἕξεις. οὐ μικρὸν οὖν διαφέρει τὸ οὕτως ἢ οὕτως εὐθὺς ἐκ νέων ἐθίζεσθαι, ἀλλὰ πάμπολυ, μᾶλλον δὲ τὸ πᾶν.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Nicomachean Ethics [Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια], Book 2, ch. 1 (2.1, 1103b.20ff) (c. 325 BC) [tr. Rackham (1934), sec. 7-8]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:

Or, in one word, the habits are produced from the acts of working like to them: and so what we have to do is to give a certain character to these particular acts, because the habits formed correspond to the differences of these. So then, whether we are accustomed this way or that straight from childhood, makes not a small but an important difference, or rather I would say it makes all the difference.

[tr. Chase (1847)]

And indeed, in a word, all habits are formed by acts of like nature to themselves. And hence it becomes our duty to see that our acts are of a right character. For, as our acts vary, our habits will follow in their course. It makes no little difference, then, to what kind of habituation we are subjected from our youth up; but it is, on the contrary, a matter that is important to us, or rather all-important.

[tr. Williams (1869), sec. 24]

In a word moral states are the results of activities corresponding to the moral states themselves. It is our duty therefore to give a certain character to the activities, as the moral states depend upon the differences of the activities. Accordingly, the difference between one training of the habits and another from early days is not a light matter, but is serious or rather all-important.

[tr. Welldon (1892)]

In a word, acts of any kind produce habits or characters of the same kind. Hence we ought to make sure that our acts be of a certain kind; for the resulting character varies as they vary. It makes no small difference, therefore, whether a man be trained from his youth up in this way or in that, but a great difference, or rather all the difference.

[tr. Peters (1893)]

Thus, in one word, states of character arise out of like activities. This is why the activities we exhibit must be of a certain kind; it is because the states of character correspond to the differences between these. It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.

[tr. Ross (1908)]

In a word, then, states come about from activities that are similar to them. That is why the activities must exhibit a certain quality, since the states follow along in accord with the differences between these. So it makes no small difference whether people are habituated in one way or in another way straight from childhood; on the contrary, it makes a huge one -- or rather, all the difference.

[tr. Reeve (1948)]

In short, it is by similar activities that habits are developed in men; and in view of this, the activities in which men are engaged should be of [the right] quality, for the kinds of habits which develop follow the corresponding differences in these activities. So in acquiring habit it makes no small difference whether we are acting in one way or on the contrary way right from our early youth; it makes a great difference, or rather all the difference.

[tr. Apostle (1975)]

In a word, then, like activities produce like dispositions. Hence we must give our activities a certain quality, because it is their characteristics that determine the resulting dispositions. So it is a matter of no little importance what sort of habits we form from the earliest age -- it makes a vast difference, or rather all the difference in the world.

[tr. Thomson/Tredennick (1976)]

In a word, then, like states arise from like activities. This is why we must give a certain character to our activities, since it is on the differences between them that the resulting states depend. So it is not unimportant how we are habituated from our early days; indeed it makes a huge difference -- or rather all the difference.

[tr. Crisp (2000)]

And so, in a word, the characteristics come into being as a result of the activities akin to them. Hence we must make our activities be of a certain quality, for the characteristics correspond to the differences among the activities. It makes no small difference, then, whether one is habituated to this or that way straight from childhood but a very great difference -- or rather the whole difference.

[tr. Bartlett/Collins (2011)]

All other knowledge is hurtful to him who has not the science of goodness.

[Toute autre science, est dommageable à celuy qui n’a la science de la bonté.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 1, ch. 24 “Of Pedantry” (1580) [tr. Cotton (1686), rev Hazlitt (1877)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

- "Each other science is prejudciall unto him that hath not the science of goodnesse." [tr. Florio (1603)]

- "All other knowledge is detrimental to him who has not the science of becoming a good man." [tr. Friswell (1868)]

- "All other learning is hurtful to him who has not the knowledge of honesty and goodness." [tr. Rector (1899)]

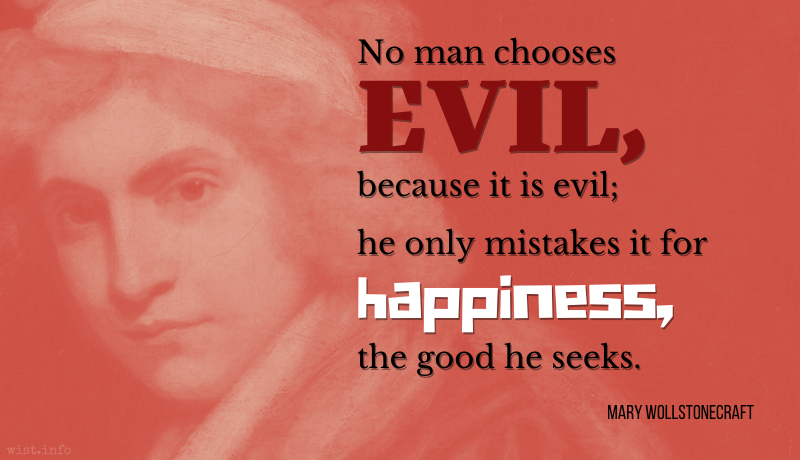

It may be confidently asserted that no man chooses evil, because it is evil; he only mistakes it for happiness, the good he seeks.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) English social philosopher, feminist, writer

A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790)

(Source)

Whether or not birth control is eugenic, hygienic, and economic, it is the most revolutionary practice in the history of sexual morals.

Walter Lippmann (1889-1974) American journalist and author

A Preface To Morals, ch. 19 (1929)

(Source)

Nothing could be less worthy of you than to think anything worse than dishonor, infamous behavior, and wickedness. To escape these, any pain is not so much as to be avoided as to be sought voluntarily, undergone, and welcomed.

[Quid enim minus est dignum quam tibi peius quicquam videri dedecore flagitio turpitudine? Quae ut effugias, quis est non modo recusandus, sed non ultro adpetendus subeundus excipiendus dolor?]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Tusculan Disputations [Tusculanae Disputationes], Book 2, ch. 5 (2.5) / sec. 14 [Marcus] (45 BC) [tr. Douglas (1990)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:

For what is more unsuitable to that high Character, than for you to think any thing worse, than dishonour, scandal, baseness? to avoid which, what Pain would not only not be declin'd, but also be eagerly pursu'd, undergone, encounter'd?

[tr. Wase (1643)]

For what is so unbecoming? What can appear worse to you, than disgrace, wickedness, immorality? To avoid which, what pain should we not only not refuse, but willingly take on ourselves?

[tr. Main (1824)]

For what is less worthy than for anything to appear worse to you than disgrace, turpitude, wickedness? which to escape, what pain is to be refused, or rather not to be welcomed, sought for, embraced?

[tr. Otis (1839)]

For what is so unbecoming -- what can appear worse to you, than disgrace, wickedness, immorality? To avoid which, what pain is there which we ought not (I will not say to avoid shirking, but even) of our own accord to encounter, and undergo, and even to court?

[tr. Yonge (1853)]

For what is more unworthy than that anything should seem to you worse than disgrace, crime, baseness? To escape these what pain should be not only not shunned, but voluntarily sought, endured, welcomed?

[tr. Peabody (1886)]

There is nothing more unworthy than for you to think anything worse than disgrace, criminal behavior, and infamous conduct. In order to escape these, any pain is not so to be rejected, as to be actively sought out, undergone, welcomed.

[tr. Davie (2017)]

No society can exist unless the laws are respected to a certain degree. The safest way to make laws respected is to make them respectable. When law and morality contradict each other, the citizen has the cruel alternative of either losing his moral sense or losing his respect for the law.

[Aucune société ne peut exister si le respect des Lois n’y règne à quelque degré ; mais le plus sûr, pour que les lois soient respectées, c’est qu’elles soient respectables. Quand la Loi et la Morale sont en contradiction, le citoyen se trouve dans la cruelle alternative ou de perdre la notion de Morale ou de perdre le respect de la Loi.]

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) French philosopher, economist, politician

The Law [La Loi] (1850) [tr. Russell]

(Source)

Violence is often caused by a surfeit of morality and justice, at least as they are conceived in the minds of the perpetrators.

Steven Pinker (b. 1954) Canadian-American cognitive psychologist, linguist, author

The Better Angels of our Nature, ch. 3 (2011)

(Source)

The moral case for intervention is only as strong as the practicality of the mission itself. There is no moral case for doing something you’re not capable of doing.

Dexter Filkins (b. 1961) American journalist

“The Moral Logic of Humanitarian Intervention,” New Yorker (16 Sep 2019)

(Source)

It must be made clear to men that the narrow path that leadeth unto life is as crowded with adventure as the broad path that leadeth to destruction.

“It’s not as simple as that. It’s not a black and white issue. There are so many shades of grey.”

“Nope.”

“Pardon?”

“There’s no greys, only white that’s got grubby.”Terry Pratchett (1948-2015) English author

Carpe Jugulum [Rev. Mightily Oats, Granny Weatherwax] (1998)

(Source)

Character is that which reveals moral purpose, showing what kind of things a man chooses or avoid.

[ἔστιν δὲ ἦθος μὲν τὸ τοιοῦτον ὃ δηλοῖ τὴν προαίρεσιν, ὁποία τις ἐν οἷς οὐκ ἔστι δῆλον ἢ προαιρεῖται ἢ φεύγει διόπερ οὐκ ἔχουσιν ἦθος τῶν λόγων ἐν οἷς μηδ᾽ ὅλως ἔστιν ὅ τι προαιρεῖται ἢ φεύγει ὁ λέγων.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Poetics [Περὶ ποιητικῆς, De Poetica], ch. 6, sec. 17 / 1450b.9 (c. 335 BC) [tr. Butcher (1895)]

(Source)

Original Greek. The key word êthos [ἦθος] is generally given here as "character." Alternate translations:

- "Character in a play is that which reveals the moral purpose of the agents, i.e. the sort of thing they seek or avoid, where that is not obvious." [tr. Bywater (1909)]

- "Psychology in the sense of "an index to the quality of the purpose" has for its sphere places where the ulterior purposes of an immediate resolve (positive or negative) is naturally obscure." [tr. Margoliouth (1911)]

- "Character is that which reveals choice, shows what sort of thing a man chooses or avoids in circumstances where the choice is not obvious." [tr. Fyfe (1932)]

- "Character is that which reveals decision, of whatever sort." [tr. Janko (1987), sec. 3.1.3]

- "Moral character is what reveals the nature of people's fundamental options." [tr. Kenny (2013)]

Man the master, ingenious past all measure,

past all dreams the skills within his grasp —

he forges on, now to destruction,

now again to greatness. When he weaves in

the laws of the land, and the justice of the gods

that bind his oaths together

he and his city rise high —

but the city casts out

that man who weds himself to inhumanity

thanks to reckless daring. Never share my hearth,

never think my thoughts, whoever does such things.[σοφόν τι τὸ μηχανόεν τέχνας ὑπὲρ ἐλπίδ᾽ ἔχων

τοτὲ μὲν κακόν, ἄλλοτ᾽ ἐπ᾽ ἐσθλὸν ἕρπει,

νόμους γεραίρων χθονὸς θεῶν τ᾽ ἔνορκον δίκαν,

370ὑψίπολις: ἄπολις ὅτῳ τὸ μὴ καλὸν

ξύνεστι τόλμας χάριν. μήτ᾽ ἐμοὶ παρέστιος

γένοιτο μήτ᾽ ἴσον φρονῶν ὃς τάδ᾽ ἔρδει.]Sophocles (496-406 BC) Greek tragic playwright

Antigone, l. 365ff, Stasimon 1, Antistrophe 2 [Chorus] (441 BC) [tr. Fagles (1982)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

Wise in his craft of art

Beyond the bounds of expectation,

The while to good he goes, the while to evil.

Honouring his country's laws and heaven's oathbound right,

High is he in the state!

But cityless is he with whom inherent baseness dwells;

When boldness dares so much,

No seat by me at festive hearth,

No seat by me in sect or party,

For him that sinneth!

[tr. Donaldson (1848)]

Passing the wildest flight thought are the cunning and skill,

That guide man now to the light, but now to counsels of ill.

If he honors the laws of the land, and reveres the Gods of the State

Proudly his city shall stand; but a cityless outcast I rate

Whoso bold in his pride from the path of right doth depart;

Ne'er may I sit by his side, or share the thoughts of his heart.

[tr. Storr (1859)]

Inventive beyond wildest hope, endowed with boundless skill,

One while he moves toward evil, and one while toward good,

According as he loves his land and fears the Gods above.

Weaving the laws into his life and steadfast oath of Heaven,

High in the State he moves but outcast he,

Who hugs dishonour to his heart and follows paths of crime

Ne'er may he come beneath my roof, nor think like thoughts with me.v [tr. Campbell (1873)]

Possessing resourceful skill, a subtlety beyond expectation he moves now to evil, now to good. When he honors the laws of the land and the justice of the gods to which he is bound by oath, his city prospers. But banned from his city is he who, thanks to his rashness, couples with disgrace. Never may he share my home, never think my thoughts, who does these things!

[tr. Jebb (1891)]

Cunning beyond fancy's dream is the fertile skill which brings him, now to evil, now to good. When he honours the laws of the land, and that justice which he hath sworn by the gods to uphold, proudly stands his city: no city hath he who, for his rashness, dwells with sin. Never may he share my hearth, never think my thoughts, who doth these things!

[tr. Jebb (1917)]

O clear intelligence, force beyond all measure!

O fate of man, working both good and evil!

When the laws are kept, how proudly his city stands!

When the laws are broken, what of his city then?

Never may the anarchic man find rest at my hearth,

Never be it said that my thoughts are his thoughts.

[tr. Fitts/Fitzgerald (1939), l. 285ff]

O wondrous subtlety of man, that draws

To good or evil ways! Great honor is given

And power to him who upholdeth his country’s laws

And the justice of heaven.

But he that, too rashly daring, walks in sin

In solitary pride to his life’s end.

At door of mine shall never enter in

To call me friend.

[tr. Watling (1947)]

Clever beyond all dreams

the inventive crat that he has

which may drive him one time or another to well or ill.

When he honors the laws of the land and the gods' sworn right

high indeed is his city; but stateless is the man

who dares to dwell with dishonor. Not by my fire,

never to share my thoughts, who does these things.

[tr. Wyckoff (1954)]

Surpassing belief, the device and

Cunning that Man has attained,

And it bringeth him now to evil, now to good.

If he observe Law, and tread

The righteous path God ordained,

Honored is he; dishonored, the man whose reckless heart

Shall make him join hands with sin:

May I not think like him,

Nor may such an impious man

Dwell in my house.

[tr. Kitto (1962)]

He has cunning contrivance,

Skill surpassing hope,

And so he slithers into wickedness sometimes,

Other times into doing good.

If he honors the law of the land

And the oath-bound justice of the gods,

Then his city shall stand high.

But no city for him if he turns shameless out of daring.

He will be no guest of mine,

He will never share my thoughts,

If he goes wrong.

[tr. Woodruff (2001)]

Possessing a means of invention, a skillfulness beyond expectation,

now toward evil he moves, now toward good.

By integrating the laws of the earth

and justice under oath sworn to the gods,

he is lofty of city. Citiless is the man with whom ignobility

because of his daring dwells.

May he never reside at my hearth

or think like me,

whoever does such things.

[tr. Tyrell/Bennett (2002)]

And though his wisdom is great in discovery -- wisdom beyond all imaginings!

Yet one minute it turns to ill the next again to good.

But whoever honours the laws of his land and his sworn oaths to the gods, he’ll bring glory to his city.

The arrogant man, on the other hand, the man who strays from the righteous path is lost to his city. Let that man never stay under the same roof as me or even be acquainted by me!

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]

The qualities of his inventive skills

bring arts beyond his dreams and lead him on,

sometimes to evil and sometimes to good.

If he treats his country’s laws with due respect

and honours justice by swearing on the gods,

he wins high honours in his city.

But when he grows bold and turns to evil,

then he has no city. A man like that --

let him not share my home or know my mind.

[tr. Johnston (2005), l. 415ff]

With clever creativity beyond expectation, he moves now to evil, now to good. The one who observes the laws of the land and justice, our compat with the gods, is honored in the city, but there is no city for one who participates in what is wrong for the sake of daring. Let him not share my hearth, nor let me share his ideas who had done these things.

[tr. Thomas (2005)]

I believe that censorship grows out of fear, and because fear is contagious, some parents are easily swayed. Book banning satisfies their need to feel in control of their children’s lives. This fear is often disguised as moral outrage. They want to believe that if their children don’t read about it, their children won’t know about it. And if they don’t know about it, it won’t happen.

But no moral philosopher, from Aristotle to Aquinas, to John Locke and Adam Smith, divorced economics from a set of moral ends or held the production of wealth to be an end in itself; rather it was seen as a means to the realization of virtue, a means of leading a civilized life.

Nothing so outrages the feelings of the church as a moral unbeliever — nothing so horrible as a charitable Atheist.

If nobody were to know or even to suspect the truth, when you do anything to gain riches or power or sovereignty or sensual gratification — if your act should be hidden for ever from the knowledge of gods and men, would you do it? […] Should they answer that, if impunity were assured, they would do what was most to their selfish interest, that would be a confession that they are criminally minded; should they say that they would not do so, they would be granting that all things in and of themselves immoral should be avoided.

[Si nemo sciturus, nemo ne suspicaturus quidemn sit, curn aliquid divitiarum, potentiae, dominationis, libidinis causa feceris, si id dis hominibusque futurum sit semper ignotuml, sisne facturus. […] Si responderint se impunitate proposita facturos, quod expediat, facinorosos se esse fateantur, si negent, omnia turpia per se ipsa fugienda esse concedant.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 3, ch. 9 (3.9) / sec. 39 (44 BC) [tr. Miller (1913)]

(Source)

Attacking the Epicurean philosophy that people are deterred from evil acts, not because they are evil, but because they might be caught. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Suppose you could do any dishonest action, for the gratifying of a lustful, covetous, or ambitious desire, so as that no one living could either know or suspect it, but both gods and men must be kept perfectly in ignorance; whether in such case would you do it or no? [...] If they say they would gratify such desires on assurance of impunity, we may know them to be villains by their own confession; but if they deny it, they may be forced to grant that every base and dishonest action is barely as such to be shunned and detested.

[tr. Cockman (1699)]

If no man should know, or not even suspect, that you were any way engaged in the pursuit of wealth, power, or domination, or for the gratification of lust; and if it were to be forever unknown to gods and men; would you behave so? [...] If they answer, upon impunity being proposed, they would do what is profitable, they may confess themselves profligate, but if they refuse that they would follow such a course, they admit that every vice from its own nature ought to be avoided.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]

If nobody were to know, nobody even to suspect that you were doing anything for the sake of riches, power, domination, lust -- if it would be for ever unknown to gods and men, would you do it? [...] If they answer that they would do, if impunity were offered, what it was their interest to do, they must confess that they are wicked; if they deny that they would do so, they must admit that all base actions are to be shunned on their own account.

[tr. Edmonds (1865)]

If no one would ever know, if no one would ever suspect, when you performed some act for the sake of wealth, power, ascendency, lust, -- if it would remain forever unknown to gods and men, would you do it? [...] If they answer that they would do what seemed expedient if assured of impunity, they may confess themselves atrociously guilty; and if they make the contrary answer, that they may grant that whatever is wrong in itself ought to be shunned.

[tr. Peabody (1883)]

Would you gratify your desire for riches, power, dominion, or sensual pleasure, if you had no fear of detection or even of suspicion, and were certain that the act would for ever be unknown to gods and men? [...] If they replied that they would do what was best for themselves if assured of impunity, they would thereby admit their criminal intention ; if they said they would not, they would grant that every shameful act must be shunned on its own account.

[tr. Gardiner (1899)]

If no one were to know, if no one were even to suspect when you were about to commit a crime to gain wealth, power, ascendancy, or sexual satisfaction, if this fact were to remain unknown for lal time to the gods and to men, would you go ahead and do it? [...] If they replied that they would perform actions for their personal advantage if they had a guarantee of impunity, they would admit they were criminal types. If they said they would not, they would concede that all immortal acts must be avoided at all times.

[tr. Edinger (1974)]

In their moral justification, the argument of the lesser evil has played a prominent role. If you are confronted with two evils, thus the argument runs, it is your duty to opt for the lesser one, whereas it is irresponsible to refuse to choose altogether. […] Politically, the weakness of the argument has always been that those who choose the lesser evil forget very quickly that they chose evil.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) German-American philosopher, political theorist

“Personal Responsibility Under Dictatorship” (1964)

(Source)

We have a tendency to condemn people who are different from us, to define their sins as paramount and our own sinfulness as being insignificant.

Jimmy Carter (b. 1924) American politician, US President (1977-1981), Nobel laureate [James Earl Carter, Jr.]

“A Statesman And a Man Of Faith,” interview by Don Lattin, San Francisco Chronicle (12 Jan 1997)

(Source)

One strain in Protestant thinking has always looked to economic life not just for its efficacy in producing goods and services but as a vast apparatus of moral discipline, of rewards for virtue and industry and punishments for vice and indolence.

Richard Hofstadter (1916-1970) American historian and intellectual

“Pseudo-Conservatism Revisited — 1965,” sec. 3 (1965)

(Source)