Awl plezzures are lawful that don’t end in making us feel sorry.

[All pleasures are lawful that don’t end in making us feel sorry.]Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 148 “Affurisms: Ink Brats” (1874)

(Source)

Quotations about:

regret

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

It does not undo harm to acknowledge that we have done it; but it undoes us not to acknowledge it.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 4 (1963)

(Source)

Whoever too precipitately yields

To anger, shall find sorrow at the last:

For wrath unbridled oft deceives mankind.[Οργή γάρ όστις ευθέως χαρίζεται ,

Κακώς τελευτά πλείστα γάρ σφάλλει βρoτούς .]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Æolus [Αἴολος], frag. 31 (TGF) [tr. Wodhull (1809)]

(Source)

Nauck frag. 31, Barnes frag. 62, Musgrave frag.3. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translation:

Whoever yields to anger suffers a piteous end.

[Source]

“If Mr. Darcy is neither by honour nor inclination confined to his cousin, why is not he to make another choice? And if I am that choice, why may not I accept him?”

“Because honour, decorum, prudence, nay, interest, forbid it. Yes, Miss Bennet, interest; for do not expect to be noticed by his family or friends, if you wilfully act against the inclinations of all. You will be censured, slighted, and despised, by everyone connected with him. Your alliance will be a disgrace; your name will never even be mentioned by any of us.”

“These are heavy misfortunes,” replied Elizabeth. “But the wife of Mr. Darcy must have such extraordinary sources of happiness necessarily attached to her situation, that she could, upon the whole, have no cause to repine.”Jane Austen (1775-1817) English author

Pride and Prejudice, ch. 56 [Elizabeth and Lady Catherine] (1813)

(Source)

The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.

I will apologise for many things that I have done, but I will not apologise for the things that should never be apologised for. It is a little theory of mine that has much exercised my mind lately, that most of the problems of this silly and delightful world derive from our apologising for those things which we ought not to apologise for, and failing to apologise for those things for which apology is necessary.

Stephen Fry (b. 1957) British actor, writer, comedian

Moab Is My Washpot, “Falling In,” ch. 3 (1997)

(Source)

Vesuvius, once latticed with vine shade,

With grapes from which the richest wine was made —

This is where Bacchus had his favorite haunt

And Satyrs could their wildest dances vaunt.

Here Venus more than Sparta made her place.

Here Hercules brought blessings for the race.

What once in beauty and renown was cherished

In fire and ashes has with horror perished.

Were it allowed immortal gods to rue it,

They would have wished they were not doomed to do it.[Hic est pampineis viridis modo Vesbius umbris,

Presserat hic madidos nobilis uva lacus:

Haec iuga, quam Nysae colles, plus Bacchus amavit,

Hoc nuper Satyri monte dedere choros.

Haec Veneris sedes, Lacedaemone gratior illi,

Hic locus Herculeo numine clarus erat.

Cuncta iacent flammis et tristi mersa favilla:

Nec superi vellent hoc licuisse sibi.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 4, epigram 44 (4.44) (AD 89) [tr. Wills (2007)]

(Source)

On the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in AD 79, which destroyed the towns of Pompeii (whose patron was Venus) and Herculaneum (supposedly founded by Hercules), as well as much of the surrounding countryside.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Vesuvius shaded once with greenest vines,

Where pressed grapes did yield the noblest wines.

Which hills far more they say Bacchus lov'd,

Where Satyrs once in mirthfull dances mov'd,

Where Venus dwelt, and better lov'd the place

Than Sparta; where Alcides Temple was,

Is now burnt downe, rak'd up in ashes sad.

The gods are griev'd that such great power they had.

[tr. May (1629)]

Vesuvio, cover'd with the fruitful vine,

Here flourish'd once, and ran with floods of wine.

here Bacchus oft to the cool shades retir'd,

And his own native Nisa less admir'd:

Oft to the mountain's airy tops advanc'd,

The frisking Satyrs on the summits danc'd.

Alcides here, here Venus grac'd the shore,

Nor lov'd her fav'rite Lacedæmon more!

Now piles of ashes , spreading all around

In undistinguish'd heaps, deform the ground.

The gods themselves the ruin'd seats bemoan;

And blame the mischiefs that themselves have done.

[tr. Addison (1705)]

Vesuvius this! So lately crown'd with vines!

Whence in full currents flowed the generous wines!

By Bacchus more than Nysa's hills belov'd!

Upon whose top in dance the satyrs mov'd!

The seat of Venus, more than Sparta dear!

Proud of her name Heraclea once was here!

All drown'd in flames! with ashes cover'd o'er!

the gods, who caus'd the ill, their power deplore.

[tr. Hay (1755)]

Here Vesuvius late with rich festoons was green:

Here noblest clusters gusht a lake serene.

These beyond Nysa's hights the god advanc'd:

On this glad moutnain gamesom satyrs danc'd.

This, more than Sparta, joy'd the laughing dame:

These summits prouden'd by Alcides' name.

Smoke, embers, flames, have laid the glories low:

The pow'rs regret the very pow'r they glow.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 4, part 1, ep. 33]

Yonder is Vesuvius, lately verdant with the shadowy vines; there a noble grape under pressure yielded copious lakes of wine; that hill Bacchus preferred to the hills of Nysa; there lately the Satyrs led their dances; there Venus had a residence more agreeable to her than Lacedæmon; that spot was made illustrious by the name of Hercules. Now, every thing is laid low by flames, and is buried under the sad ashes. Surely the Gods must regret that they possessed so much power for mischief.

[tr. Amos (1858), ch. 7, ep. 167]

This is Vesuvius, lately green with umbrageous vines; here the noble grape had pressed the dripping coolers. These are the heights which Bacchus loved more than the hills of Nysa; on this mountain the satyrs recently danced. This was the abode of Venus, more grateful to her than Lacedaemon; this was the place renowned by the divinity of Hercules. All now lies buried in flames and sad ashes. Even the gods would have wished not to have had the power to cause such a catastrophe.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

This is Vesbius, green yesterday with viny shades; here had the noble grape loaded the dripping vats; these ridges Bacchus loved more than the hills of Nysa; on this mount of late the Satyrs set afoot their dances; this was the haunt of Venus, more pleasant to her than Lacedaemon; this spot was made glorious by the name of Hercules. All lies drowned in fire and melancholy ash; even the High Gods could have wished this had not been permitted them.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Fair were thy shading vines and rich to fill

The overflowing wine-press year by year,

Bacchus hath loved thee more than Nysa’s hill,

Vesuvius, for his fauns held revel here;

Sweet Venus held no other haunt so dear,

Alcides made thee glorious with his name,

Flame-swept art thou, a waste of ashes drear,

And heaven remorseful hides its face for shame.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

Vesuvius here was green with mantling vine,

Here brimming vats o'erflowed with noble wine.

These hills to jocund Bacchus were more dear

Than Nysa, and the Satyrs reveled here.

This blest retreat could Cytherea please,

This owned the fame of godlike Hercules;

Now dismal ashes all and scorching flame.

Such dire caprice might move a god to shame.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), ep. 84]

Behold Vesuvius, lately green

With vineyard-covered slopes!

Here did the noble grapevine yield

Beyond one's wildest hopes!

Here are the ridges Bacchus loves

More than those of his youth.

And here till late his Satyrs danced

There merry dance uncouth.

Here stood Pompeii, dearer far

To Aphrodite than

The Lacedaemonian island where

Her early life began.

And here stood Herculaneum,

Founded by Hercules

Where here he paused to rest the oxen

Of Geryones.

All this, by fire and flame consumed,

Lies sunk, so sad a sight

The very gods might wish they had

Not had it in their might.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Only a short while ago old smoky Vesuvius

bore a green burden of vineyards on his shoulders

and the vats below were clogged with gorgeous grapes.

This was a place whose forests high in the air meant more to Bacchus than his Nysean hills.

And only a short while ago Satyrs led their troupes down this same mountainside. Here were Venus’ haunts

more appealing to her than Sparta.

And this whole landscape knew the sound of Hercules’ roving name. He too made it holy.

And now, there it lies submerged in ashes,

crumpled, shorn by the flames,

so curiously at odds

with the will of the gods

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Hear the testament of death:

yesterday beneath Vesuvius' side

the grape ripened in green shade,

the dripping vats with their viny tide

squatted on hill turf: Bacchus

loved this land more than fertile Nysa:

here the satyrs ran, this was Venus' home,

sweeter to her than Lacedaemon

or the rocks of foam-framed Cyprus.

One city now in ashes the great name

of Hercules once blessed, one other

to the salty sea was manacled.

All is cold silver, all fused with death

murdered by the fire of Heaven. Even

the Gods repent this faculty

that power of death which may not be recalled.

[tr. Porter (1972)]

This is Vesuvius, yesterday green with shady vines.

Here notable grapes weighted down the wine-steeped vats.

These the heights that Bacchus loved more than Nysa's hills.

On this mountain the Satyrs began their dances lately.

This was Venus' seat, more pleasing to her than Sparta.

This place was made renowned by Hercules' godhead.

All lies sunk in flames and bleak ash. Even the high gods

Could wish that this had not been allowed to them.

[tr. Shepherd (1987)]

This is Vesuvius, but lately green with shade of vines. Here the noble grape loaded the vats to overflowing. These slopes were more dear to Bacchus than Nysa's hills, on this mountain not long ago Satyrs held their dances. This was Venus' dwelling, more pleasing to her than Lacedaemon, this spot the name of Hercules made famous. All lies sunk in flames and drear ashes. The High Ones themselves would rather this had not been in their power.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

Here is Vesuvius, viney and shade-green only yesterday;

here, on these slopes Bacchus loved more than Nysa’s hills,

the noble grapes outgave themselves time and again;

on this mountain the Satyrs leaped and danced,

for this was Venus’s adopted home, dearer to her than Sparta,

and here a proud town bore the name of Hercules.

It’s all drowned now by fire, sunk to drab ash. What won’t

the high gods permit themselves, they could well ask.

[tr. Matthews (1995)]

This is Vesuvius, green just now with vines;

here fine grapes loaded brimming vats. These heights

were loved by Bacchus more than Nysa's slopes;

on this mount, satyrs lately danced their rites.

this home of Venus pleased her more than Sparta;

this spot the name of Hercules made proud.

All lie engulfed in flames and dismal ashes:

the gods themselves regret it was allowed.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

The fact I asked you last night

To come round this evening and dine,

Procillus, would seem to be due

To that fifth or sixth bottle of wine.

To think it entirely arranged

And take notes on the nonsense you hear

Is a hazardous way to behave —

D–n a drinker whose memory’s clear![Hesterna tibi nocte dixeramus,

Quincunces puto post decem peractos,

Cenares hodie, Procille, mecum.

Tu factam tibi rem statim putasti

Et non sobria verba subnotasti

Exemplo nimium periculoso:

Μισῶ μνάμονα συμπόταν, Procille.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 1, epigram 27 (1.27) (AD 85-86) [tr. Nixon (1911), “A Alleybi’s the Thing”]

(Source)

"To Procillus." The Greek phrase, attested to elsewhere in Classical literature, reads, as variously translated here, "I dislike a drinking companion who remembers."

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

I had this day carroust the thirteenth cup,

And was both slipper-tong'd, and idle-brain'd,

And said by chance, that you with me should sup.

You thought hereby, a supper cleerely gain'd:

And in your Tables you did quote it up.

Uncivill ghest, that hath been so ill train'd!

Worthy thou are hence supperlesse to walke,

That tak'st advantage of our Table-talke.

[tr. Harington (fl. c. 1600)]

To sup with me, to thee I did propound,

But 'twas when our full cups had oft gone round.

The thing thou straight concludest to be done,

Merry and sober words counting all one.

Th' example's dangerous at the highest rate;

A memorative drunkard all men hate.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]

Yesternight, it seems, I swore,

Fifty bumpers hardly o'er,

You should sup tonight with me;

Instant you devour'd the glee;

And would bind the words of drink:

Dang'rous precedent, I think.

Wofull partner of the bowl,

Proves a reminiscent soul.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 7, ep. 17]

Last night I had invited you -- after some fifty glasses, I suppose, had been despatched -- to sup with me today. You immediately thought your fortune was made, and took note of my unsober words, with a precedent but too dangerous. I hate a boon companion whose memory is good, Procillus.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

Last night I said to you (I think it was after I had got through ten half-pints): "Dine with me today, Procillus." You at once thought the matter settled for you, and took secret note of my unsober remark -- a precedent too dangerous! "I hate a messmate with a memory," Procillus.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

I may have asked you here to dine,

But that was late at night,

And none of us had spared the wine

If I remember right.

You thought the invitation meant,

Though wine obscured my wit!

And -- O most parous precedent --

You made a note of it!

The maxim that in Greece was true

Is true in Rome today --

"I hate a fellow-toper who

Remembers what I say."

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "'Tis Wise to Forget"]

After ten cups were put away

I said, "Procillus," yesterday,

"You'll dine with me, my friend, you're wanted."

You promptly took the thing for granted

And made a note without formality

Of my incautious hospitality;

A dangerous precedent to set;

I hate a guest who won't forget.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #16]

Last night I said, while feeling fine,

Having drunk much too much wine,

That you must promise, when this way,

To stop and dine with me some day.

You made a mental note of it,

A practice which, I must admit --

Taking me at my drunken word! --

Is dangerous and quite absurds.

Barroom promises are fine,

But he who keeps them is a swine!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Last night in my cups,

or my brandy tumbler, at least,

I asked you for dinner today.

But you took me seriously, Procillus,

and noted down carefully the words I spouted

under the influence. A dangerous business.

I don't like to drink with people who remember.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]

Last night, after five pints of wine,

I said, "Procillus, come and dine

Tomorrow." You assumed I meant

What I said (a dangerous precedent)

And slyly jotted down a note

Of my drunk offer. Let me quote

A proverb from the Greek: "I hate

An unforgetful drinking mate."

[tr. Michie (1972)]

Last night when I was carried off with wine

I made you promise to drop by and dine

With me today. Only a fool or a turd

Expects a drunken man to keep his word.

[tr. O'Connell (1991), "Bummer"]

Last night after getting through four pints or so I asked you to dine with me this evening, Procillus. You thought you had the matter settled then and there, and made a mental note of my tipsy words -- a very dangerous precedent. I don't like a boozing partner with a memory, Procillus.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

When drinks I had beyond my number,

I thought I would myself encumber

With a pledge to give you lunch today.

You wrote it down with great display

As if to register disputed votes.

I hate a tippler taking notes.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

Last night, Procillus, after I had drunk

four pints or so, I asked if you would dine

with me today. At once, you thought the matter

was settled, based on statements blurred by wine --

a risky precedent. Good memory

is odious in one who drinks with me.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

Last night I invited you,

after we killed, what, fifty-something cups,

to come and eat some food with me today.

Right then and there you thought the thing was done

and took me at my not-so-sober word.

A very risky thing to do: I hate

a drinking bud whose memory is good.

[tr. Goldman (2022)]

Make your choice, adventurous Stranger,

Strike the bell and bide the danger,

Or wonder, till it drives you mad,

What would have followed if you had.C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) English writer, literary scholar, lay theologian [Clive Staples Lewis]

The Magician’s Nephew, ch. 4 “The Bell and the Hammer” (1955)

(Source)

Inscription below the bell in Charn.

Timely advis’d, the coming Evil shun:

Better not do the Deed, than weep it done.Matthew Prior (1664-1721) English poet and diplomat

“Henry and Emma,” l. 310ff [Henry] (1709)

(Source)

From a wretched deed there is sometimes a good outcome, making penance even more unlikely than usual.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 5 (1963)

(Source)

As one who wills, and then unwills his will,

Changing his mind with every changing whim,

Till all his best intentions come to nil,

So I stood havering in that moorland dim,

While through fond rifts of fancy oozed away

The first quick zest that filled me to the brim.[E qual è quei che disvuol ciò che volle

e per novi pensier cangia proposta,

sì che dal cominciar tutto si tolle,

tal mi fec’ïo ’n quella oscura costa,

perché, pensando, consumai la ’mpresa

che fu nel cominciar cotanto tosta.]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 1 “Inferno,” Canto 2, l. 37ff (2.37-42) (1309) [tr. Sayers (1949)]

(Source)

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:

As he who what he first resolv'd rejects,

And by some fresher reasons is induc'd

Wholly to lay aside his first intent;

So I, now in the mountain's shade arriv'd,

Refus'd th' attempt which I at first desir'd.

[tr. Rogers (1782), ll. 34-38]

Like one, who, some imagin'd peril near,

Feels his warm wishes chill'd by wint'ry fear,

And resolution sicken at the view,

Thus I perceiv'd my sinking spirits fail,

Thus trembling, I survey'd the gloomy vale,

As near the moment of decision drew.

[tr. Boyd (1802), st. 8]

As one, who unresolves

What he hath late resolv'd, and with new thoughts

Changes his purpose, from his first intent

Remov'd; e'en such was I on that dun coast,

Wasting in thought my enterprise, at first

So eagerly embrac'd.

[tr. Cary (1814)]

As one that what he wished unwisheth now,

And, changing purpose in a newer drift.

Doth his first motion wholly disallow;

So wrought I then beneath that gloomy cliff,

Who, meditating, quenched the venturous hope

That in her first beginning rose so swift.

[tr. Dayman (1843)]

And as one who unwills what he willed, and with new thoughts changes his purpose, so that he wholly quits the thing he commenced,

such I made myself on that dim coast: for with thinking I wasted the enterprise, that had been so quick in its commencement.

[tr. Carlyle (1849)]

Like one unwilling for the thing he wills,

Whose second thoughts have made his purpose pale,

And everything upon the threshold fail;

So did I with myself obscure that coast

With thinking much -- the enterprise gave o'er

With vehemence I had embraced before.

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]

And as with him unwishing what he wish'd,

Who changes purpose as new thoughts arise,

So that his first intentions pass away;

It was with me when on that coast obscure;

For as thought grew, the enterprise was lost,

Which at the first so quickly I desir'd.

[tr. Johnston (1867)]

And as he is, who unwills what he willed,

And by new thoughts doth his intention change,

So that from his design he quite withdraws,

Such I became, upon that dark hillside,

Because, in thinking, I consumed the emprise,

Which was so very prompt in the beginning.

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]

And as is he who ceases to will that he willed, and by reason of new thoughts changes purpose, so that he withdraws himself wholly from his beginning, so became I on that dark hillside; so that in my thought I made an end of the enterprise which in its commencement had been so hasty.

[tr. Butler (1885)]

Like unto one who wills not that he would,

And shifts his purpose with thought's changing tide,

So that he dare not make commencement good,

Thus acted I on that hill's darkened side;

In idle thought I wasted the emprise.

To which so swiftly I first had hied.

[tr. Minchin (1885)]

And as is he who unwills what he willed, and because of new thoughts changes his design, so that he quite withdraws from beginning, such I became on that dark hillside: wherefore in my thought I abandoned the enterprise which had been so hasty in the beginning.

[tr. Norton (1892)]

And as one who wisheth not that which he wished, and for new fancies changeth his resolve, so that he turns him wholly from his undertaking; even in such state was I on that dark slope; for, while I pondered, I brought to naught the enterprise, that was at first so readily embraced.

[tr. Sullivan (1893)]

And as one is who what he wished unwishes,

And for new thoughts exchanges his set purpose,

So that he quite departs from his beginnings,

Such I became upon that gloomy hillside;

Because in thought the enterprise I wasted

Which had at the beginning been so eager.

[tr. Griffith (1908)]

And as one who unwills what he willed and with new thoughts changes his purpose so that he quite withdraws from what he has begun, such I became on that dark slope; for by thinking of it I brought to naught the enterprise that was so hasty in its beginning.

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]

And like one who unwills what he willed first

And new thoughts change the intention that he had,

So that his resolution is reversed,

So on that dim slope did my purpose fade

For I with thinking had dulled down the zest

That at the outset sprang so prompt and glad.

[tr. Binyon (1943)]

As one who unwills what he wills, will stay

strong purposes with feeble second thoughts

until he spells all his first zeal away --

so I hung back and balked on that dim coast

till thinking had worn out my enterprise,

so stout at starting and so early lost.

[tr. Ciardi (1954)]

And like one who unwills what he has willed and with new thoughts changes his resolve, so that he quite gives up the thing he had begun, such did I become on that dark slope, for by thinking on it I rendered null the undertaking that had been so suddenly embarked upon.

[tr. Singleton (1970)]

As one who unwills what he willed, will change

his purposes with some new second thought,

completely quitting what he first had started,

so I did, standing there on that dark slope,

thinking, ending the beginning of that venture

I was so quick to take up at the start.

[tr. Musa (1971)]

And just as he who unwills what he wills

and shifts what he intends to seek new ends

so that he's drawn from what he had begun,

so was I in the midst of that dark land,

because, with all my thinking, I annulled

the task I had so quickly undertaken.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1980)]

And just like somebody who shilly-shallies,

And thinks again about what he has decided,

So that he gives up everything he has started,

I found I was on that obscure hillside:

By thinking about it I spoiled the undertaking

I had been so quick to enter in the first place.

[tr. Sisson (1981)]

And then, like one who unchooses his own choice

And thinking again undoes what he has started,

So I became: a nullifying unease

Overcame my soul on that dark slope and voided

The undertaking I had so quickly embraced.

[tr. Pinsky (1994), ll. 31-35]

And like one who unwills what he just now willed and with new thoughts changes his intent, so that he draws back entirely from beginning:

so did I become on that dark slope, for, thinking, I gave up the undertaking that I had been so quick to begin.

[tr. Durling (1996)]

And I rendered myself, on that dark shore, like one who un-wishes what he wished, and changes his purpose, in new thinking, so that he leaves off what he began, completely, since in thought I consumed action, that had been so ready to begin.

[tr. Kline (2002)]

As one who unwills what he willed,

and eyes another half-baked project,

so I bore away from my initial enterprise

and shilly-shallied on that twilit shore,

while dim thoughts flitted through my cranium

obscuring what I'd once been eager for.

[tr. Carson (2002)]

And so -- as though unwanting every want,

so altering all at every altering thought

now drawing back from everything begun --

I stood there on the darkened slope, fretting

away from thought to thought the bold intent

that seemed so very urgent at the outset.

[tr. Kirkpatrick (2006)]

And as one who unwills what he has willed,

changing his intent on second thought

so that he quite gives over what he has begun,

such a man was I on that dark slope.

With too much thinking I had undone

the enterprise so quick in its inception.

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]

Like someone half regretting what once seemed knowledge,

intention shifted around by fresh ideas,

Starting to throw all old ones overboard,

I stood on that dark slope, pulled by feelings

So murky they dissipated whatever I'd thought

I knew, surrendering what once seemed real.

[tr. Raffel (2010)]

Just so, obeying the unwritten rule

That one who would unsieh that which he wished,

Having thought twice about what he first sought,

Must put fish back into the pool he fished,

So they, set free, may once again be caught,

Just so did I in that now shadowy fold --

Because, by thinking, I'd consumed the thought

I started with, that I had thought so bold.

[tr. James (2013)]

Oft to the town he turns his eyes,

Whence Dido’s fires already rise.

What cause has lit so fierce a flame

They know not: but the pangs of shame

From great love wronged, and what despair

Can make a baffled woman dare —

All this they know, and knowing tread

The paths of presage, vague and dread.[… moenia respiciens, quae iam infelicis Elissae

conlucent flammis. Quae tantum accenderit ignem,

causa latet; duri magno sed amore dolores

polluto, notumque, furens quid femina possit,

triste per augurium Teucrorum pectora ducunt.]Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

The Aeneid [Ænē̆is], Book 5, l. 4ff (5.4-8) (29-19 BC) [tr. Conington (1866)]

(Source)

Elissa is an alternate name for Dido.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Viewing unhappy Dido's wals, which shone

With flames, the cause such fire had rais'd, unknown;

But what a woman might in sorrow drown'd,

Struck deep with grief and burning love was found;

And by sad auguries Trojans understand.

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]

Then, casting back his eyes, with dire amaze,

Sees on the Punic shore the mounting blaze.

The cause unknown; yet his presaging mind

The fate of Dido from the fire divin'd;

He knew the stormy souls of womankind,

What secret springs their eager passions move,

How capable of death for injur'd love.

Dire auguries from hence the Trojans draw;

Till neither fires nor shining shores they saw.

[tr. Dryden (1697)]

... looking back at the walls which now glare with the flames of unfortunate Elisa. What cause may have kindled such a blaze is unknown; but the thought of those cruel agonies that arise from violent love when injured, and the knowledge of what frantic woman can do, led the minds of the Trojans through dismal forebodings.

[tr. Davidson/Buckley (1854)]

He saw the city glaring with the flames

Of the unhappy Dido. What had lit

This fire, they knew not; but the cruel pangs

From outraged love, and what a woman's rage

Could do, they know; and through the Trojans' thoughts

Pass sad forebodings of the truth.

[tr. Cranch (1872)]

... looking back on the city that even now gleams with hapless Elissa's funeral flame. Why the broad blaze is lit lies unknown; but the bitter pain of a great love trampled, and the knowledge of what woman can do in madness, draw the Teucrians' hearts to gloomy guesses.

[tr. Mackail (1885)]

... Still looking back upon the walls now litten by the flame

Of hapless Dido: though indeed whence so great burning came

They knew not; but the thought of grief that comes of love defiled

How great it is, what deed may come of woman waxen wild,

Through woeful boding of the sooth the Teucrians' bosoms bore.

[tr. Morris (1900)]

... And backward on the city bent his gaze,

Bright with the flames of Dido. Whence the blaze

Arose, they knew not; but the pangs they knew

When love is passionate, and man betrays,

And what a frantic woman scorned can do,

And many a sad surmise their boding thoughts pursue

[tr. Taylor (1907)]

... but when his eyes

looked back on Carthage, they beheld the glare

of hapless Dido's fire. Not yet was known

what kindled the wild flames; but that the pang

of outraged love is cruel, and what the heart

of desperate woman dares, they knew too well,

and sad foreboding shook each Trojan soul.

[tr. Williams (1910)]

... looking back on the city walls which now gleam with unhappy Elissa's funeral flames. What cause kindled so great a flame is unknown; but the cruel pangs when deep love is profaned, and knowledge of what a woman can do in frenzy, lead the hearts of the Trojans amid sad forebodings.

[tr. Fairclough (1916)]

His gaze went back

To the walls of Carthage, glowing in the flame

Of Dido’s funeral pyre. What cause had kindled

So high a blaze, they did not know, but anguish

When love is wounded deep, and the way of a woman

With frenzy in her heart, they knew too well,

And dwelt on with foreboding.

[tr. Humphries (1951)]

He looked back at Carthage's walls; they were lit up now by the death-fires

Of tragic Dido. Why so big a fire should be burning

Was a mystery: but knowing what a woman is capable of

When insane with the grief of having her love cruelly dishonoured

Started a train of uneasy conjecture in the Trojans' minds.

[tr. Day-Lewis (1952)]

... gazing

back -- watching where the walls of Carthage glowed

with sad Elissa's flames. They cannot know

what caused so vast a blaze, and yet the Trojans

know well the pain when passion is profaned

and how a woman driven wild can act;

their hearts are drawn through dark presentiments.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1971)]

But he kept his eyes

Upon the city far astern, now bright

With poor Elissa's pyre. What caused that blaze

Remained unknown to watchers out at sea,

But what they knew of a great love profaned

In anguish, and a desperate woman's nerve,

Led every Trojan heart into foreboding.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1981)]

... looking back at the walls of Carthage, glowing now in the flames of poor Dido's pyre. No one understood what had lit such a blaze, but since they all knew what bitter suffering is caused when a great love is desecrated and what a woman is capable when driven to madness, the minds of the Trojans were filled with dark foreboding.

[tr. West (1990)]

... looking back at the city walls that were glowing now with

unhappy Dido’s funeral flames. The reason that such a fire had

been lit was unknown: but the cruel pain when a great love is

profaned, and the knowledge of what a frenzied woman might do,

drove the minds of the Trojans to sombre forebodings.

[tr. Kline (2002)]

... he glanced back at the walls of Carthage

set aglow by the fires of tragic Dido’s pyre.

What could light such a conflagration? A mystery --

but the Trojans know the pains of a great love

defiled, and the lengths a woman driven mad can go,

and it leads their hearts down ways of grim foreboding.

[tr. Fagles (2006)]

... gazing back at city walls lit up by the flames -- poor Dido's pyre. No one knew what caused the blaze, but they knew the great grief of a love betrayed and what a woman's passion could unleash. Their hearts were somber with foreboding.

[tr. Bartsch (2021)]

Weep not that the world changes — did it keep

A stable, changeless state, ’twere cause indeed to weep.William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) American poet and editor

“Sonnet — Mutation,” ll. 13-14 (1824)

(Source)

In the middle of the night, things well up from the past that are not always cause for rejoicing — the unsolved, the painful encounters, the mistakes, the reasons for shame or woe. But all, good or bad, give me food for thought, food to grow on.

May Sarton (1912-1995) Belgian-American poet, novelist, memoirist [pen name of Eleanore Marie Sarton]

At Seventy (1984)

(Source)

No one on his deathbed ever said, “I wish I had spent more time on my business.”

Paul Tsongas (1941-1997) American politician

Heading Home (1984), quoting Arnold Zack

(Source)

Often misattributed directly to Tsongas, this was quoted from a letter from Zack, a Massachusetts lawyer and old friend, during Tsongas' battle with cancer.

There are so many things that we wish we had done yesterday, so few that we feel like doing today.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Second Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 10 (1966)

(Source)

Grief is the agony of an instant; the indulgence of Grief the blunder of a life.

Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) English politician and author

Vivian Grey, Book 6, ch. 7 (1826)

(Source)

You want to cry aloud for your

mistakes. But to tell the truth the world

doesn’t need any more of that sound.Mary Oliver (1935-2019) American poet

“The Poet With His Face in His Hands,” New Yorker (4 Apr 2005)

(Source)

Collected in New and Selected Poems, Vol. 2 (2005), and The Best American Poetry, 2006.

Four be the things I am wiser to know:

Idleness, sorrow, a friend, and a foe.Four be the things I’d been better without:

Love, curiosity, freckles, and doubt.Three be the things I shall never attain:

Envy, content, and sufficient champagne.Three be the things I shall have till I die:

Laughter and hope and a sock in the eye.Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) American writer

“Inventory,” Life (11 Nov 1926)

(Source)

Reprinted in Enough Rope (1926).

There are few of us who are not protected from the keenest pain by our inability to see what it is that we have done, what we are suffering, and what we truly are. Let us be grateful to the mirror for revealing to us our appearances only.

Samuel Butler (1835-1902) English novelist, satirist, scholar

Erewhon, ch. 3 “Up the River” (1872)

(Source)

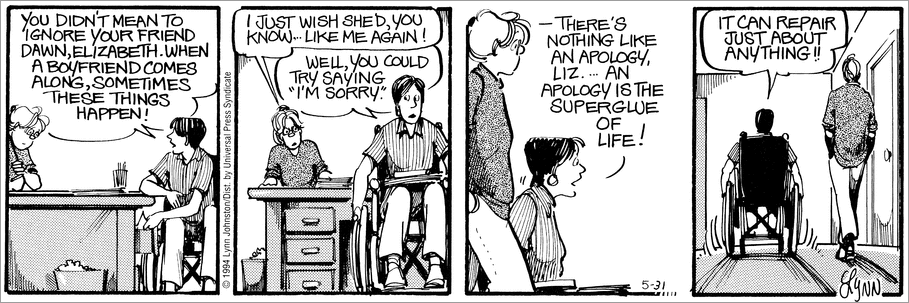

Apologies rebuild the bridge that gets severed when we hurt someone else, either intentionally or by accident. Apologies don’t require us to grovel or wallow in guilt. We simply acknowledge that our actions were insensitive, unkind, or harmful and say we are sorry.

Charlotte Kasl (d. 2021) American psychologist and author

If the Buddha Dated: A Handbook for Finding Love on a Spiritual Path (1999)

(Source)

Right actions for the future are the best apologies for wrong ones in the past — the best evidence of regret for them that we can offer, or the world receive.

Tryon Edwards (1809-1894) American theologian, writer, lexicographer

A Dictionary of Thoughts (1908)

(Source)

Often wrongly quoted, "... best apologies for bad actions in the past."

APOLOGIZE, v.i. To lay the foundation for a future offense.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) American writer and journalist

“Apologize,” The Cynic’s Word Book (1906)

(Source)

Included in The Devil's Dictionary (1911).

The essence of good manners consists in making it clear that one has no wish to hurt. When it is clearly necessary to hurt, it must be done in such a way as to make it evident that the necessity is felt to be regrettable.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

“Good Manners and Hypocrisy,” New York American (1934-12-14)

(Source)

A good man can expand his life: he lives

twice over whose past life can be enjoyed.[Ampliat ætatis spatium sibi vir bonus. Hoc est

Vivere bis, vita posse priore frui.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 10, epigram 23 (10.23.8-9) (AD 95, 98 ed.) [tr. McLean (2014)]

"To Antonius Primus." (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:

Thus good men to themselves long life can give,

T' enjoy our former life is twice to live.

[tr. May (1629)]

Each must, in vertue, strive for to excell;

That man lives twice, that lives the first life well.

[tr. Herrick (1648)]

He liveth twice, who can the Gift retain

Of Mem'ry, to enjoy past Life again.

[tr. Cotton (1685)]

Thus a good man prolongs his mortal date;

Lives twice, enjoying thus his former slate.

[tr. Hay (1755)]

For he lives twice who can at once employ

The present well, and e'en the past enjoy.

[tr. Pope (1713)]

They stretch the limits of this narrow span;

And, by enjoying, live past life again.

[tr. Lewis (1750)]

A good man amplifies the span of his existence ; for this is to live twice, to be able to find enjoyment in past life.

[tr. Amos (1858); he gives several other contemporary uses and translations.]

A good man lengthens his term of existence; to be able to enjoy our past life is to live twice.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]

So good men lengthen life; and to recall

The past, is to have twice enjoyed it all.

[tr. Stevenson (c. 1883)]

The good man prolongs his life; to be able to enjoy one's past life is to live twice.

[Bartlett's (1891)]

A good man has a double span of life,

For to enjoy past life is twice to live.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]

A good man widens for himself his age's span; he lives twice who can find delight in life bygone.

[tr. Ker (1919)]

Redoubled happiness and life hath he

Whose joy doth live again in memory.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]

The good man lengthens out his earthly skein,

For living in the past is life again.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #525]

A good man's life is doubly long,

For he lives twice who, day and night,

Can in his whole past take delight.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]

Virtue extends our days: he lives two lives who relives his past with pleasure.

[Bartlett's (1968)]

A good man enlarges for himself his span of life. To be able to enjoy former life is to live twice over.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]

The good man has no ugly past he would forget,

So memory gives him doubled life without regret.

[tr. Ericsson (1995)]

He does not deplore life's brevity.

For virtue is itself longevity.

[tr. Wills (2007)]

When I remember,

success, failure,

friend, enemy,

wife, lover

I live twice over.

[tr. Kennelly (2008), "Living"]

A good man can expand his life: he lives

twice over whose past life can be enjoyed.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

The good man broadens for himself the span of his years: to be able to enjoy the life you have spent, is to live it twice.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all your Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all your Tears wash out a Word of it.

Omar Khayyám (1048-1123) Persian poet, mathematician, philosopher, astronomer [عمر خیام]

Rubáiyát [رباعیات], Bod. # 31, etc. [tr. FitzGerald, 2nd Ed (1868), # 76]

(Source)

All Fitzgerald editions after the 2nd used the same text but numbered as # 71. The 1st Ed. was very similar, only using "thy" instead of "your," and numbered as # 51.

Fitzgerald seems to have merged at least three different fatalistic quatrains into this famous one of his: Bodleian #31, 54, and 95. Fitzgerald's use of a finger as the writing implement, rather the pen and pencils of other translators, seems taken from Daniel 5 in the Bible.

Alternate translations:

Bodleian # 31

All things that be were long since marked upon the tablet of creation. Heaven's pencil has naught to do with good or evil. God set on fate its necessary seal; and all our efforts are but a vain striving.

[tr. McCarthy (1879), # 86] (1888)

To me there is much comfort in the thought

That all our agonies can alter nought,

Our lives are written to their latest word,

We but repeat a lesson He hath taught.

[tr. Le Gallienne (1897), # 93]

Whatever betides on the Tablet of Destiny writ is;

Of good and of evil thenceforward the Pen Divine quit is:

In Fate foreordained whatsoever behoveth It 'stablished:

Our stress and our strife and our thought-taking vain every whit is.

[tr. Payne (1898), # 191]

From the beginning was written what shall be;

Unhaltingly the Pen writes, and is heedless of good and bad;

On the First Day He appointed everything that must be --

Our grief and our efforts are vain.

[tr. Heron-Allen (1898), # 31]

Long, long ago, man's fate was graven clear,

The pen left nought unwrit of joy or woe;

Since from eternity God ruled it so

Then senseless are our grief and striving here.

[tr. Cadell (1899), # 11]

Ere yet the dawn of Azal shed its light

O'er dreary chaos and the realms of night,

The Pen, unmoved by good and evil, wrote;

Nor grief can change, nor endless toil rewrite.

[tr. Roe (1906), # 21]

Fate's marks upon the tablet still remain

As first, the Pen unmoved by bliss or bane;

In fate whate'er must be it did ordain,

To grieve or to resist is all in vain.

[tr. Thompson (1906), # 69]

For He, to whom all future things are known,

E'en as He made thee wrote thy record down;

And what His pen hath written, good or ill,

No strife may alter, and no grief atone.

[tr. Talbot (1908), # 31]

From of old the scheme of all that must be has existed.

The pen of destiny has written good and evil without ceasing.

He has appointed in predestination all that must come.

We distress and bestir ourselves, but all to no avail.

[tr. Christensen (1927), # 91]

Before now there have been signs of what is to come,

The pen never rests from good or evil.

Destiny has given you all that is to be,

Our worries and our endeavours are in vain.

[tr. Rosen (1928), # 53]

His tablet bears the future but concealed,

His pen is calm if good or bad we yield.

The powers gave us proper share at first,

With grief or strife no less nor more we wield.

[tr. Tirtha (1941), # 6.16]

What we shall be is written, and we are so.

Heedless of God or Evil, pen, write on!

By the first day all futures were decided;

Which gives our griefs and pains irrelevancy.

[tr. Graves & Ali-Shah (1967), # 75]

The characters of all creatures are on the Tablet,

The Pen always worn with writing "Good," "Bad":

Our grieving and striving are in vain,

Before time began all that was necessary was given.

[tr. Avery/Heath-Stubbs (1979), # 26]

Signs of destiny have always been

Those hands inscribed both good and mean

What was written, came from the unseen

Though we tried without and worried within.

[tr. Shahriari (1998), # 24, literal]

One is great

Who faces fate

Before it’s late,

Appreciate

The destined state

No matter how much we debate

Oppose, engage, or calculate

Even try to accelerate

Fate only moves at its own rate.

Futile is worry, anger and hate

Joy is the only worthy mate.

[tr. Shahriari (1998), # 24, figurative]

Bodleian # 54

Yes, since whate'er the Pen of Fate has traced

For Tears of Man will never be erased,

Support thy Ills, do not bemoan thy Lot,

Let all of Fate's Decrees be bravely faced.

[tr. Garner (1887), 4.4]

Whatever laws the pen of Fate has traced

For tears of man will never be erased;

Support thy ills, do not bemoan thy lot,

Let all of Fate's decrees be boldly faced.

[tr. Garner (1898), # 83]

What the Pen has written never changes,

and grieving only results in deep affliction;

even though, all thy life, thou sufferest anguish,

not one drop becomes increased beyond what is.

[tr. Heron-Allen (1898), # 54]

Nought can be changed of what was first decreed,

Grieve as thou wilt, no heart but thine will bleed;

If thy life long, thine eyes shed tears of blood,

'Twill not increase one drop woe's raging flood.

[tr. Cadell (1899), # 89]

For what is written, be it long or brief,

Remains the same, nor tears can give relief;

No drop of destiny is less nor more,

Though naught you know but lifelong pain and grief.

[tr. Roe (1906), # 24]

To change the written scroll there is no power.

And grieving only makes your heart bleed sore.

Though anguish all your life consume your blood.

You cannot add to it one drop the more.

[tr. Thompson (1906), # 73]

Whate'er the Pen hath written stands for aye:

Afflictions's sword the grieving heart will slay;

Though all thy life with anguish thou art wrung,

The forward march of Fate thou canst not stay.

[tr. Talbot (1908), # 54]

The Fate will not correct what once she writes,

And more than what is doled no grain alights;

Beware of bleeding heart with sordid cares,

For cares will cast thy heart in wretched plights.

tr. Tirtha (1941), # 6.12]

Bodleian # 95

Oh my heart, since life's reality is illusion,

Why vex thyself with its sorrows and cares?

Commit thee to fate, contented with the hour,

For the pen, once passed, returns not back for thee!

[tr. Cowell (1858), # 15]

Since life has, love! no true reality,

Why let its coil of cares a trouble be?

Yield thee to Fate, whatever of pain it bring:

The Pen will never unwrite its writ for thee!

[tr. M. K. (1888)]

O heart! this world is but a fleeting show,

Why should its empty griefs distress thee so?

Bow down and bear thy fate, the eternal pen

Will not unwrite its roll for thee, I trow!

[tr. Whinfield (1883), # 257]

O heart, my heart, since the very basis of all this world's gear is but a fable, why do you adventure in such an infinite abyss of sorrows? Trust thyself to fate, uphold the evil, for what the pencil has traced will not be effaced for you.

[tr. McCarthy (1879), # 159] (1888)

Oh, heart! since in this world truth itself is hyperbole,

why art thou so disquieted with this trouble and abasement?

resign thy body to destiny, and adapt thyself to the times,

for, what the Pen has written, it will not rewrite for thy sake.

[tr. Heron-Allen (1898), # 95]

O heart! 'tis true that all this world is vain,

Wherefore then eat the fruit of sorrow's tree?

To fate thy body yield, endure the pain;

The once split pen will never mend for thee.

[tr. Cadell (1899), # 100]

O, Heart! Since earth's truth is illusion vain,

Why so distressed in lasting grief and pain?

Bear trouble ! Bow to Fate ! Once gone the Pen

For thee will never trace the scroll again!

[tr. Thompson (1906), # 300]

O heart! truth absolute thou canst not see,

Then why abase theyself in misery?

Bow down to Fate, and wrestle not with Time!

The pen will not rewrite one word for thee.

[tr. Talbot (1908), # 95]

Oh heart, as in truth the world is but a delusion,

Why grieve so much at this dearth of kindness?

Give thyself up to fate and befriend thy sorrow,

For this pen will not retrace its writing for thee.

[tr. Rosen (1928), # 170]

O mind! the world is but a mocking sight,

You fancy some delights, and fret in fright;

Resign yourself to Him, and pine for Him,

You cannot alter what is black on white.

tr. Tirtha (1941), # 6.11]

Oh heart, since the world's reality is illusion,

How long will you complain about this torment?

Resign your body to fate and put up with the pain,

Because what the Pen has written for you it will not unwrite.

[tr. Avery/Heath-Stubbs (1979), # 32]

There is also this: when we renounce the self and become part of a compact whole, we not only renounce personal advantage but are also rid of personal responsibility. There is no telling to what extremes of cruelty and ruthlessness a man will go when he is freed from the fears, hesitations, doubts and the vague stirrings of decency that go with individual judgement. When we lose our individual independence in the corporateness of a mass movement, we find a new freedom — freedom to hate, bully, lie, torture, murder and betray without shame and remorse. Herein undoubtedly lies part of the attractiveness of a mass movement.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, Part 3, ch. 14, § 77 (1951)

(Source)

Proud people breed sad sorrows for themselves.

Emily Brontë (1818-1848) British novelist, poet [pseud. Ellis Bell]

Wuthering Heights, ch. 7 (1847) [Nelly Dean]

(Source)

Don’t commit suicide, because you might change your mind two weeks later.

Art Buchwald (1925-2007) American humorist, columnist

Leaving Home (1995)

A personal mantra Buchwald used to combat his intermittent depression. Possibly borrowed from Voltaire.

You couldn’t get hold of the things you’d done and turn them right again. Such a power might be given to the gods, but it was not given to women and men, and that was probably a good thing. Had it been otherwise, people would probably die of old age still trying to rewrite their teens.

Most men spend the best part of their lives making the remaining part wretched.

[La plupart des hommes emploient la meilleure partie de leur vie à rendre l’autre misérable.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 11 “Of Mankind [De l’Homme],” § 102 (11.102) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

The greatest part of mankind employ their first years to make their last miserable.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]

The greatest part of Mankind imploy their first Years to make their last miserable.

[Curll ed. (1713)]

The greatest part of Mankind employ their first Years to make their last miserable. [Browne ed. (1752)]

Most men employ the first years of their life in making the last miserable.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

Most men make use of the first part of their life to render the last part miserable.

[Source]

But the greatest gift in the power of loneliness to bestow is the realization that life does not consist either of wallowing in the past or of peering anxiously at the future; and it is appalling to contemplate the great number of often painful steps by which one arrives at a truth so old, so obvious, and so frequently expressed. It is good for one to appreciate that life is now. Whether it offers little or much, life is now — this day — this hour — and is probably the only experience of the kind one is to have.

The secret of health for both mind and body is not to mourn for the past, worry about the future, or anticipate troubles, but to live in the present moment wisely and earnestly.

BRUTUS: The abuse of greatness is, when it disjoins

Remorse from power.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Julius Caesar, Act 2, sc. 1, l. 19ff (2.1.19-20) (1599)

(Source)

Things said or done long years ago,

Or things I did not do or say

But thought that I might say or do,

Weigh me down, and not a day

But something is recalled,

My conscience or my vanity appalled.William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) Irish poet and dramatist

“Vacillation,” st. 4 (1932), The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1933)

(Source)

But we live through the fine days without noticing them; only when we fall on evil ones do we wish to have back the former. With sour faces we let a thousand bright and pleasant hours slip by unenjoyed and afterwards vainly sigh for their return when times are trying and depressing. Instead of this, we should cherish every present moment that is bearable, even the most ordinary, which with such indifference we now let slip by, and even with impatience push on.

[Aber wir verleben unsre schönen Tage, ohne sie zu bemerken: erst wann die schlimmen kommen, wünschen wir jene zurück. Tausend heitere, angenehme Stunden lassen wir, mit verdrießlichem Gesicht, ungenossen an uns vorüberziehn, um nachher, zur trüben Zeit, mit vergeblicher Sehnsucht ihnen nachzuseufzen. Statt dessen sollten wir jede erträgliche Gegenwart, auch die alltägliche, welche wir jetzt so gleichgültig vorüberziehn lassen, und wohl gar noch ungeduldig nachschieben.]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. 1, “Aphorisms on the Wisdom of Life [Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit],” ch. 5 “Counsels and Maxims [Paränesen und Maximen],” § 2.5 (1851) [tr. Payne (1974)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:

But we live through our days of happiness without noticing them; it is only when evil comes upon us that we wish them back. A thousand gay and pleasant hours are wasted in ill-humor; we let them slip by unenjoyed, and sigh for them in vain when the sky is overcast. Those present moments that are bearable, be they never so trite and common, -- passed by in indifference, or, it may be, impatiently pushed away.

[tr. Saunders (1890)]

That what cannot be repaired is not to be regretted.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) English writer, lexicographer, critic

The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia, ch. 4 (1759)

(Source)

Men repent speaking ten times, for once that they repent keeping silence.

James Burgh (1714-1775) British politician and writer

The Dignity of Human Nature, Sec. 5 “Miscellaneous Thoughts on Prudence in Conversation” (1754)

(Source)