Thrust into life without my own consent,

Thrust back to death, with who knows what intent?

Arise, bright saki, fill the cup with wine

And drown the burden of my discontent.

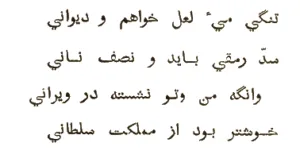

Omar Khayyám (1048-1123) Persian poet, mathematician, philosopher, astronomer [عمر خیام]

Rubáiyát [رباعیات], Bod. # 21 [tr. Roe (1906), # 44]

(Source)

A saki or sāqī (ساقی) means "wine-server" or "bartender."

Alternate translations:My coming was not of mine own design,

And one day I must go, and no choice of mine;

Come, light-handed cupbearer, gird thee to serve,

We must wash down the care of this world with wine.

[tr. Cowell (1858), # 8]What, without asking, hither hurried whence

And, without asking, wither hurried hence!

Another and another Cup to drown

The Memory of this Impertinence!

[tr. FitzGerald, 1st ed. (1859), # 30]What, without asking, hither hurried whence

And, without asking, wither hurried hence!

Ah, contrite Heav'n endowed us with the Vine

To drug the memory of that insolence.

[tr. FitzGerald, 2nd ed. (1868), # 33]What, without asking, hither hurried Whence?

And, without asking, Whither hurried hence!

Oh, many a Cup of this forbidden Wine

Must drown the memory of that insolence!

[tr. FitzGerald, 3rd ed. (1872), # 30; 4th ed. (1879); 5th ed. (1889)]O Cup-Bearer, since Time lurks hard by ready to shatter you and me, this world can never be an abiding dwelling for you and me. But come what may, assure yourself that God is in our hands while this cup of wine stands between you and me.

[tr. McCarthy (1879), # 35]I came not hither of my own free will,

And go against my wish, a puppet still;

Cupbearer! gird thy loins and fetch some wine;

To purge the world's despite, my goblet fill.

[tr. Whinfield (1883), # 110; (1882) # 641]Since hither, willy nilly, I came the other day

And hence must soon be going, without my yea or nay,

Up, cupbearer! thy middle come gird without delay;

The world and all its troubles with wine I 'll wash away.

[tr. Payne (1898), # 94]Seeing that my coming was not for me the Day of Creation,

and that my undesired departure hence is a purpose fixed for me,

get up and gird well thy loins, O nimble Cup bearer,

for I will wash down the misery of the world in wine.

[tr. Heron-Allen (1898), # 21]As my first coming was no wish of mine

So my departure I can not devise.

Gird thyself, Saki! Fair bright Saki rise,

Lest time should fail to drink this skin of wine.

[tr. Cadell (1899), # 37]Since coming at the first was naught of mine,

And I unwilling go by fixed design,

Cupbearer, rise! and quickly gird thy loins!

For worldly sorrows I'll wash down in wine!

[tr. Thompson (1906), # 157]I was not asked to choose my natal morn,

I die as helplessly as I was born.

Bring wine, and I will strive to wash away

The recollection of Creation's scorn.

[tr. Talbot (1908), # 21]Since my coming was not of my own choosing from

the first day, and my going has been irrevocably fixed without my will,

arise and gird thy loins, o nimble Sáqí, for I will

wash down the grief of the world with wine.

[tr. Christensen (1927), # 32]Since here I came unwilling and perforce,

To go unplanning is my proper course;

Arise O Guide! and girdle up thy waist,

And with Thy Word absolve me from remorse.

[tr. Tirtha (1941), # 8.72]My presence here has been no choice of mine;

Fate hounds me most unwillingly away.

Rise, wrap a cloth about your loins, my Saki,

And swill away the misery of this world.

[tr. Graves & Ali-Shah (1967), # 32]Since at first my coming was not at my will,

And the going is involuntarily imposed,

Arise, fasten your belt brisk wine-boy,

I'll drown the world's sorrow in wine.

[tr. Avery/Heath-Stubbs (1979), # 94]

Quotations about:

wine

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

You sleep, gaping,

On your bags of gold, adore them like hallowed

Relics not meant to be touched, stare as at gorgeous

Canvases. Money is meant to be spent, it buys pleasure:

Did you know that? Bread, vegetables, wine, you can

Buy almost everything it’s hard to live without.[Congestis undique saccis

indormis inhians et tamquam parcere sacris

cogeris aut pictis tamquam gaudere tabellis.

Nescis, quo valeat nummus, quem praebeat usum?

Panis ematur, holus, vini sextarius, adde

quis humana sibi doleat natura negatis.]Horace (65-8 BC) Roman poet, satirist, soldier, politician [Quintus Horatius Flaccus]

Satires [Saturae, Sermones], Book 1, # 1, “Qui fit, Mæcenas,” l. 70ff (1.1.70-75) (35 BC) [tr. Raffel (1983)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Thy house, the hell, thy good, the flood, which, thoughe it doe not starte,

Nor stirre from thee, yet hath it so in houlde thy servyle hearte,

That though in foysonne full thou swimmes, and rattles in thy bagges,

Yet tost thou arte with dreadefulle dreames, thy mynde it waves and wagges,

And wisheth after greater things, and that, thats woorste of all,

Thou sparst it as an hollye thynge, and doste thy selfe in thralle

Unto thy lowte, and cockescome lyke thou doste but fille thine eye

With that, which shoulde thy porte preserve, and hoyste thyne honor hye.

Thou scannes it, and thou toots upponte, as thoughe it were a warke

By practysde painters hande portrayde with shaddowes suttle darke.

Is this the perfytte ende of coyne? be these the veray vayles

That money hath, to serve thy syghte? fye, fye thy wysedome fayles.

Tharte misse insenste, thou canst not use't, thou wotes not what to do

Withall, by cates, bye breade, bye drincke, in fyne disburse it so,

That nature neede not move her selfe, nor with a betments scant

Distrainte, and prickd passe forth her daye in pyne and pinchinge want.

[tr. Drant (1567)]Thee,

Who on thy full cramb'd Bags together laid,

Do'st lay thy sleepless and affrighted head;

And do'st no more the moderate use on't dare

To make, then if it consicrated were:

Thou mak'st no other use of all thy gold,

Then men do of their pictures, to behold.

Do'st thou not know the use and power of coyn?

It buys bread, meat, and cloaths, (and what's more wine;)

With all those necessary things beside,

Without which Nature cannot be suppli'd.

[tr. A. B.; ed. Brome (1666)]Thou watchest o'er thy heaps, yet 'midst thy store

Thou'rt almost starv'd for Want, and still art poor:

You fear to touch as if You rob'd a Saint,

And use no more than if 'twere Gold in paint:

You only know how Wealth may be abus'd,

Not what 'tis good for, how it can be us'd;

'Twill buy Thee Bread, 'twill buy Thee Herbs, and

What ever Nature's Luxury can grant.

[tr. Creech (1684)]Of thee the tale is told,

With open mouth when dozing o'er your gold.

On every side the numerous bags are pil'd,

Whose hallow'd stores must never be defil'd

To human use ; while you transported gaze,

As if, like pictures, they were form'd to please.

Would you the real use of riches know?

Bread, herbs, and wine are all they can bestow:

Or add, what nature's deepest wants supplies;

This, and no more, thy mass of money buys.

[tr. Francis (1747)]O'er countless heaps in nicest order stored

You pore agape, and gaze upon the hoard,

As relicks to be laid with reverence by,

Or pictures only meant to please the eye.

With all your cash, you seem not yet to know

Its proper use, or what it can bestow!

"'Twill buy me herbs, a loaf, a pint of wine, --

All, which denied her, nature would repine."

[tr. Howes (1845)]You sleep upon your bags, heaped up on every side, gaping over them, and are obliged to abstain from them, as if they were consecrated things, or to amuse yourself with them as you would with pictures. Are you ignorant of what value money has, what use it can afford? Bread, herbs, a bottle of wine may be purchased; to which [necessaries], add [such others], as, being withheld, human nature would be uneasy with itself.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]You sleepless gloat o'er bags of money gained from every source, and yet you're forced to touch them not as though tabooed, or else you feel but such delight in them as painting gives the sense. Pray don't you know the good of money to you, or the use it is? You may buy bread and herbs, your pint of wine, and more, all else, which if our nature lacked, it would feel pain.

[tr. Millington (1870)]Of you the tale is told:

You sleep, mouth open, on your hoarded gold;

Gold that you treat as sacred, dare not use,

In fact, that charms you as a picture does.

Come, will you hear what wealth can fairly do?

'Twill buy you bread, and vegetables too,

And wine, a good pint measure: add to this

Such needful things as flesh and blood would miss.

[tr. Conington (1874)]You sleep with open mouth on money-bags piled up from all sides, and must perforce keep hands off as if they were hallowed, or take delight in them as if painted pictures. Don't you know what money is for, what end it serves? You may buy bread, greens, a measure of wine, and such other things as would mean pain to our human nature, if withheld.

[tr. Fairclough (Loeb) (1926)]You sleep on the sacks

Of money you've scraped up and raked in from everywhere

And, gazing with greed, are still forced to keep your hands off,

As if they were sacred or simply pictures to look at.

Don't you know what money can do, or just why we want it?

It's to buy bread and greens and a pint of wine

And the things that we, being human, can't do without.

[tr. Palmer Bovie (1959)]You have money bags amassed from everywhere,

just to sleep and gasp upon. To you they're sacred,

or they're works of art, to be enjoyed only with the eyes.

Don't you know the value of money, what it's used for?

It buys bread, vegetables, a pint of wine and whatever else

a human being needs to survive and not to suffer.

[tr. Fuchs (1977)]You sleep with open mouth

on sacks accumulated from everywhere

and are constrained to worship them as sacred things,

or rejoice in them as if they were painted tablets.

Do you not know what money serves for?

How it's to be used? to buy bread, vegetables,

a sixth of wine, other things deprived of which

human nature suffers.

[tr. Alexander (1999)]You sleep open-mouthed on a mound of money

bags but won't touch them; you just stare at them

as if they were a collection of paintings.

What's money for? What can it do? Why not

buy bread, vegetables, what you think's wine enough?

Don't you want what it harms us not to have?

[tr. Matthews (2002)]You scrape your money-bags together and fall asleep

on top of them with your mouth agape. They must remain unused

like sacred objects, giving no more pleasure than if painted on canvas.

Do you not realize what money is for, what enjoyment it gives?

You can buy bread and vegetables, half a litre of wine,

and the other things which human life can't do without.

[tr. Rudd (2005 ed.)]... covetously sleeping on money-bags

Piled around, forced to protect them like sacred objects,

And take pleasure in them as if they were only paintings.

Don’t you know the value of money, what end it serves?

Buy bread with it, cabbages, a pint of wine: all the rest,

Things where denying them us harms our essential nature.

[tr. Kline (2015)]

Sometimes I wondered if it even mattered whether our communion cups were filled with consecrated wine or draft beer, as long as we bent over them long enough to recognize each other as kin.

Barbara Brown Taylor (b. 1951) American minister, academic, author

Learning to Walk in the Dark, ch. 2 (2014)

(Source)

Then to the Lip of this poor earthen Urn

I lean’d, the Secret of my Life to learn:

And Lip to Lip it murmur’d — “While you live,

“Drink! — for, once dead, you never shall return.”

Omar Khayyám (1048-1123) Persian poet, mathematician, philosopher, astronomer [عمر خیام]

Rubáiyát [رباعیات], Bod. # 100 [tr. FitzGerald, 3rd ed. (1872), # 35]

(Source)

The same translation was used by Fitzgerald for the 4th ed. (1879) and 5th ed. (1889).

Where there are numerological references (which multiple sources pull together as variations on this quatrain), they are based on the numbering: One man, two worlds, four elements, five senses, seven planets, eight heavens, nine spheres, ten powers.

Alternate translations:Lip to lip I passionately kissed the bowl,

To learn from it the secret of length of days;

Lip to lip in answer it whispered reply,

"Drink wine, for once gone thou shalt never return!"

[tr. Cowell (1858), # 25]Then to this earthen Bowl did I adjourn

My Lip the secret Well of Life to learn:

And Lip to Lip it murmur'd -- "While you live,

"Drink! -- for once dead you never shall return."

[tr. FitzGerald, 1st ed. (1859), # 34]Then to the Lip of this poor earthen Urn

I lean'd, the secret Well of Life to learn:

And Lip to Lip it murmur'd -- "While you live,

"Drink! -- for, once dead, you never shall return."

[tr. FitzGerald, 2nd ed. (1868), # 34]O offspring of the four and five, art puzzled by the four and five? Drink deep, for I have told thee time on time, that once departed, thou returnest no more.

[tr. McCarthy (1879), # 245]I put my lips to the cup, for I did yearn

The secret of the future life to learn;

And from his lip I heard a whisper drop,

"Drink! for once gone you never will return."

[tr. Whinfield (1882), # 149]I put my lips to the cup, for I did yearn

The means of gaining length of days to learn;

It leaned its lip to mine, and whispered low,

"Drink! for, once gone, you never will return."

[tr. Whinfield (1883), # 152, elsewhere # 274]I put my lips to the cup, for I did yearn

The hidden cause of length of days to learn;

He leaned its lip to mine, and whispered low,

"Drink! for, once gone, you never will return."

[tr. Whinfield (188?), # 274]Slave of four elements and sevenfold heaven,

Who aye bemoan the thrall of these eleven,

Drink! I have told you seventy times and seven,

Once gone, nor hell will send you back, nor heaven.

[tr. Whinfield (1882), #223]Child of four elements and sevenfold heaven,

Who fume and sweat because of these eleven,

Drink! I have told you seventy times and seven,

Once gone, nor hell will send you back, nor heaven.

[tr. Whinfield (1883), # 431]Sprung from the Four, and the Seven! I see that never

The four and the Seven respond to thy brain's endeavour --

Drink wine! for I tell thee, four times o'er and more,

Return there is none! -- Once gone, thou art gone for ever!

[tr. M. K. (1888)]Lip to lip with the jar you know not what is intended

That is to say my lip also was like your lips (employed)

In the end since existence is no longer available

Your lips should be thus employed according to the friendly order.

[tr. Heron-Allen (1897), Calcutta # 227]In great desire I pressed my lips to the lip of the jar,

To inquire from it how long life might be attained;

It joined its lip to mine and whispered: --

"Drink wine, for, to this world, thou returnest not."

[tr. Heron-Allen (1898), # 100]With strong desire my lips the cup's lip sought

From it the cause of weary life to learn.

Its lip pressed my lips close and whisperèd: --

"Drink, in this world no moment can return."

[tr. Cadell (1899), # 110]I prest my lip in yearning to the urn.

Thereby the means of length of life to learn.

And lip to my lip placed it whispered low,

"Drink! For to this world you will ne'er return!"

[tr. Thompson (1906), # 320]To the jar's mouth my eager lip I press'd,

For Life's Elixir making anxious quest;

It join'd its lip to mine, and whisper'd low --

"Drink wine: thou shalt not wake from thy last rest!"

[tr. Talbot (1908), # 100]I laid my lip to the lip of the wine-cup in the utmost

desire to seek from it the means of prolonging life.

It laid its lip to my lip and said mysteriously: "During

a whole life I was like thee; rejoice for a while in my company."

[tr. Christensen (1927), # 65]I placed my lip on the lip of the jug and caught from it

The means of attaining a long life.

The jug then seemed to say to me:

"For a lifetime I have been as you; now, for a while, be my companion."

[tr. Rosen (1928), # 177]My lip to lip of Jar I close in glee,

In hopes that life eternal I would see;

Then quoth the Jar: Like thee I once have been

For ages, hence a minute breathe with me."

[tr. Tirtha (1941), # 5.29]Greedily to the bowl my lips I pressed

and asked how might I sue for green old age.

Pressing its lips to mine it muttered darkly:

"Drink up! Once gone, you shall return no more!"

[tr. Graves & Ali-Shah (1967), # 36]I laid my lip against the pitcher's lip in the extremity of desire, that I might seek from it the means of long life: it laid (its) lip upon my lip and said secretly, "I too was (once) like thee: consort with me for a moment."

[tr. Bowen (1976), # 19, after Heron-Allen]I pressed my lip upon the Winejar's lip,

And questioned how long life I might attain;

Then lip to lip it whispering replied:

"Drink wine -- this world thou shalt not see again."

[tr. Bowen (1976), # 19]In the extremity of desire I put my lip to the pot's

To seek the elixir of life:

It put its lip on mine and murmured,

"Enjoy the wine, you'll not be here again."

[tr. Avery/Heath-Stubbs (1979), # 139]I brought the cup to my lips with greed

Begging for longevity, my temporal need

Cup brought its to mine, its secret did feed

Time never returns, drink, of this take heed.

[tr. Shahriari (1998), literal]The only secret that you need to know

The passage of time is a one way flow

If you understand, joyously you’ll grow

Else you will drown in your own sorrow.

[tr. Shahriari (1998), figurative]

CHORUS LEADER: Ah! wine is a terrible foe, hard to wrestle with.

[ΧΟΡΟΣ: δεινὸς γὰρ οἷνος καὶ παλαίεσθαι βαρύς.]

Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Cyclops [Κύκλωψ], l. 678ff (c. 424-23 BC) [tr. Coleridge (1913)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:CHORUS: Wine is invincible.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]CYCLOPS: For wine is strong and hard to struggle with.

[tr. Shelley (1824)]CHORUS: Ah, wine’s the chap to trip your legs, I think.

[tr. Way (1916)]CHORUS-LEADER: Yes, wine is a dangerous thing and hard to wrestle against.

[tr. Kovacs (1994)]

CYCLOPS: Ha! ha! ha! I’m full of wine,

Heavy with the joy divine,

With the young feast oversated;

Like a merchant’s vessel freighted

To the water’s edge, my crop

Is laden to the gullet’s top.

The fresh meadow grass of spring

Tempts me forth thus wandering

To my brothers on the mountains,

Who shall share the wine’s sweet fountains.

Bring the cask, O stranger, bring![ΚΥΚΛΩΨ: παπαπαῖ: πλέως μὲν οἴνου,

γάνυμαι δὲ δαιτὸς ἥβᾳ,

σκάφος ὁλκὰς ὣς γεμισθεὶς

ποτὶ σέλμα γαστρὸς ἄκρας.

ὑπάγει μ᾽ ὁ φόρτος εὔφρων

ἐπὶ κῶμον ἦρος ὥραις

ἐπὶ Κύκλωπας ἀδελφούς.

φέρε μοι, ξεῖνε, φέρ᾽, ἀσκὸν ἔνδος μοι.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Cyclops [Κύκλωψ], l. 503ff (c. 424-23 BC) [tr. Shelley (1824)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:POLYPHEME: Ha! ha! I am replete with wine, the banquet

Hath cheer'd my soul: like a well-freighted ship

My stomach's with abundant viands stow'd

Up to my very chin. This smiling turf

Invites me to partake a vernal feast

With my Cyclopean brothers. Stranger, bring

That vessel from the cave.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]CYCLOPS: Ha! ha! full of wine and merry with a feast's good cheer am I, my hold freighted like a merchant-ship up to my belly's very top. This turf graciously invites me to seek my brother Cyclopes for revel in the spring-tide. Come, stranger, bring the wine-skin hither and hand it over to me.

[tr. Coleridge (1913)]CYCLOPS: Oho! Oho! I am full of good drink,

Full of glee from a good feast’s revel!

I’m a ship that is laden till ready to sink

Right up to my crop’s deck-level!

The jolly spring season is tempting me out

To dance on the meadow-clover

With my Cyclop brothers in revel-rout! --

Here, hand the wine-skin over!

[tr. Way (1916)]CYCLOPS: Ooh la la! I'm loaded up with wine, my heart skips with the cheer of the feast. My hull is full right up to the top-deck of my belly. This cheerful cargo brings me out to revel, in the springtime, to the houses of my brother Cyclopes. Come now, my friend, come now, give me the wine-skin.

[tr. Kovacs (1994)]

By the bye, as I must leave off being young, I find many douceurs [sweets] in being a sort of chaperon, for I am put on the sofa near the fire and can drink as much wine as I like.

Jane Austen (1775-1817) English author

Letter (1813-11-06) to Cassandra Austen

(Source)

Jane was 38 at the time.

ODYSSEUS: He wants to go forth, full of wine and glee,

To his brother Cyclops for wild revelry.[ΟΔΥΣΣΕΥΣ: ἐπὶ κῶμον ἕρπειν πρὸς κασιγνήτους θέλει

Κύκλωπας ἡσθεὶς τῷδε Βακχίου ποτῷ.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Cyclops [Κύκλωψ], l. 445ff (c. 424-23 BC) [tr. Way (Loeb) (1916)]

(Source)

Regarding the Cyclops keeping he and his men prisoner, and who he has introduced to the wonders of wine.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:ULYSSES: By wine enliven'd, he resolves to go

And revel with his brethren.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]ULYSSES: Delighted with the Bacchic drink he goes

To call his brother Cyclops -- who inhabit

A village upon Aetna not far off.

[tr. Shelley (1824)]ODYSSEUS: Delighted with this liquor of the Bacchic god, he fain would go a-reveling with his brethren.

[tr. Coleridge (1913)]ODYSSEUS: He wants to go to his brother Cyclopes for a revel since he is delighted with this drink of Dionysus.

[tr. Kovacs (1994)]

O my brave men! stout hearts of mine!

who often have suffered worse calamities with me.

let us now drown your cares in wine.

Tomorrow we venture once again upon the boundless sea.[O fortes peioraque passi

mecum saepe viri, nunc vino pellite curas;

cras ingens iterabimus aequor.]Horace (65-8 BC) Roman poet, satirist, soldier, politician [Quintus Horatius Flaccus]

Odes [Carmina], Book 1, # 7, l. 30ff (1.7.30-32) (23 BC) [tr. Alexander (1999)]

(Source)

To L. Munatius Plancus. Quoting Teucer to his crew on his being exiled from Salamis.

Quoted in Montaigne, 3.13 "On Experience" (immediately following this).

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Brave Spirits, who with me have suffer'd sorrow,

Drink cares away; wee'l set up sails to-morrow.

[tr. "Sir T. H.," Brome (1666)]Cheer, rouze your force,

For We have often suffer'd worse:

Drink briskly round, dispell all cloudy sorrow,

Drink round, Wee'l plow the Deep to-morrow.

[tr. Creech (1684)]Hearts, that have borne with me

Worse buffets! drown today in wine your care;

To-morrow we recross the wide, wide sea!

[tr. Conington (1872)]O gallant heroes, and often my fellow-sufferers in greater hardships than these, now drive away your cares with wine: to-morrow we will re-visit the vast ocean.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]Now, ye brave hearts, that have weather'd

Many a sorer strait with me,

Chase your cares with wine, — to-morrow

We shall plough the mighty sea!

[tr. Martin (1864)]Brave friends who have borne with me often

Worse things as men, let the wine chase to-day every care from the bosom,

To-morrow -- again the great Sea Plains.

[tr. Bulwer-Lytton (1870)]My comrades bold, to worse than this

Inured, to-morrow brave the vasty brine,

But drown to-day your cares in wine.

[tr. Gladstone (1894)]O brave friends, who have oft with your leader

Suffer'd worse trials, cheer up, let sorrows dissolve in the wine-cup,

We will try the vast ocean to-morrow.

[tr. Phelps (1897)]O brave men, often worse things ye with me

Have borne, now drive with wine your cares away,

To-morrow we will sail the wide sea once again.

[tr. Garnsey (1907)]To-night with wine drown care,

Friends oft who've braved worse things with me than these;

At morn o'er the wide sea once more we'll fare!

[tr. Marshall (1908)]O ye brave heroes, who with me have often suffered worse misfiprtunes, now banish care with wine! To-morrow we will take again our course over the mighty main.

[tr. Bennett (Loeb) (1912)]With wine now banish care;

Worse things we've known, brave hearts; once more

we'll plough the main tomorrow morn.

[tr. Mills (1924)]You who have stayed by me through worse disasters,

Heroes, come, drink deep, let wine extinguish our sorrows.

We take the huge sea on again tomorrow.

[tr. Michie (1964)]O my brave fellows who have gone through worse

Than this with me, now with the help of wine

Let's put aside our troubles for a while.

Tomorrow we set out on the vast ocean.

[tr. Ferry (1997)]O you brave heroes, you

who suffered worse with me often, drown your cares with wine:

tomorrow we’ll sail the wide seas again.

[tr. Kline (2015)]

Old wine, and an old friend, are good provisions.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

Jacula Prudentum, or Outlandish Proverbs, Sentences, &c. (compiler), # 136 (1640 ed.)

(Source)

My days of love are over; me no more

The charms of maid, wife, and still less of widow,

Can make the fool of which they made before, —

In short, I must not lead the life I did do;

The credulous hope of mutual minds is o’er,

The copious use of claret is forbid too,

So for a good old-gentlemanly vice,

I think I must take up with avarice.

Be temperate in wine, in eating, girls, and sloth;

Or the Gout will seize you and plague you both.Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1734 ed.)

(Source)

All wines don’t turn sour when they get old, and neither do all men or all personalities. I approve of sternness in the old, but a sternness that, like other things, is kept within limits; under no circumstances do I approve of bad temper.

[Ut enim non omne vinum, sic non omnis natura vetustate coacescit. Severitatem in senectute probo, sed eam, sicut alia, modicam; acerbitatem nullo modo.]Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 18 / sec. 65 (18.65) (44 BC) [tr. Copley (1967)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For as every wyne long kept and olde waxith not eagre of his owne propre nature, right so all mankynde is not aygre fell cruell ungracious chargyng nor inportune in olde age of their owne kynde though some men among many be fonde of that condicion. I approve & preyse in olde age the man which hath severitee & stidfast abydyng in hym. Seuerite is contynuance & perseverance of oon maner of lyvyng as wele in the thyngys within as in theym withoute. But I approve nat that in an olde man be egrenesse nor hardnesse & sharpnesse of maners of condicions.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]For even as every wine being old and standing long is not converted into vineigre, so likewise is not every age sour, eigre, and unpleasant. Severity and sternness in old age I well allow and commend, so that a moderate mean therein (as in all other things) be observed; but bitterness and rigorous dealing I can in no wise brook nor away withal.

[tr. Newton (1569)]For as all wines do not grow soure and tart in continuance, so not all age. I like severity in an old man, but not bitternesse.

[tr. Austin (1648), ch. 19]Our nature here, is not unlike our wine,

Some sorts, when old, continue brisk, and fine.

So Age's gravity may seem severe,

But nothing harsh, or bitter ought to appear.

[tr. Denham (1669)]In short, as it fares with Wines, so it does with Old Men: all are not equally apt to grow sour with Age. A serious and moderately grave Deportment well become us, but nothing of an austere Severity.

[tr. Hemming (1716)]Thus it is, for as all Wines are not prick'd by Age, so neither is Human Life sower'd by Old Age; a Severity I approve of in Old Men, but with Moderation; Bitterness by no means.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]Some Wines sour with Age, while others grow better and richer. A Gravity with some Severity is to be allowed; but by no means Ill nature.

[tr. Logan (1744)]As it is not every kind of wine, so neither is it every sort of temper, that turns sour by age. But I must observe at the same time there is a certain gravity of deportment extremely becoming in advanced years, and which, as in other virtues, when it preserves its proper bounds, and does not degenerate into an acerbity of manners, I very much approve.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]For, as not every wine, so not every life, grows sour by age. Strictness in old age, I approve; but that, even as other things, in moderate degree: bitterness I nowise approve.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]Neither every wine nor every life turns to vinegar with age.

[ed. Harbottle (1906)]For as it is not every wine, so it is not every man's life, that grows sour from old age. I approve of gravity in old age, but this in a moderate degree, like everything else; harshness by no means.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]For as it is not wine of every vintage, so it is not every temper that grows sour with age. I approve of gravity in old age, so it be not excessive; for moderation in all things is becoming: but for bitterness I have no tolerance.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]The fact is that, just as it is not every wine, so it is not every life, that turns sour from keeping. Serious gravity I approve of in old age, but, as in other things, it must be within due limits: bitterness I can in no case approve.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1895)]Not every wine grows sour by growing old.

Severity in age is well enough:

But not too much, and naught of bitterness.

[tr. Allison (1916)]As it is not every wine, so it is not every disposition, that grows sour with age. I approve of some austerity in the old, but I want it, as I do everything else, in moderation. Sourness of temper I like not at all.

[tr. Falconer (1923)]Human nature is like wine: it does not invariably sour just because it is old. Some old men seem very stern, and rightly so -- although there must be, as I always say, moderation in all things. There is never any reason for ill temper.

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]Certainly neither all wines go sour

Nor do all men because of agedness.

I approve of old men’s calm severity,

But I don’t put up with those who are dour.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]The truth is that a person's character, like wine, does not necessarily grow sour with age. Austerity in old age is proper enough, but like everything else it should be in moderation. Sourness of disposition is never a virtue.

[tr. Freeman (2016)]

An evil doom of some god was my undoing, and measureless wine.

[ἆσέ με δαίμονος αἶσα κακὴ καὶ ἀθέσφατος οἶνος.]

Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Odyssey [Ὀδύσσεια], Book 11, l. 61 (11.61) [Elpenor] (c. 700 BC) [tr. Murray (1919)]

(Source)

Odysseus first encounter in the Underworld is the shade of his comrade Elpenor, whose body had been left on Circe's island. This is Elpenor's explanation of his death (10.552-560). Drunk with his crew mates, he climbed a ladder to the roof of Circe's palace to sleep it off. When he heard his friends preparing to leave, he either fell from or forgot about using the ladder, plummeting to his ignominious death.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:In Circe’s house, the spite some spirit did bear,

And the unspeakable good liquor there,

Hath been my bane.

[tr. Chapman (1616)]I had come along with th’ bark,

But that the Devil and excess of wine

Made me to fall, and break my neck i’ th’ dark.

[tr. Hobbes (1675), l. 54ff]To hell my doom I owe,

Demons accursed, dire ministers of woe!

My feet, through wine unfaithful to their weight,

Betray'd me tumbling from a towery height.

[tr. Pope (1725)]Fool’d by some dæmon and the intemp’rate bowl.

[tr. Cowper (1792), ll. 69-70]I died

By stroke of fate and the dread fumes of wine.

[tr. Worsley (1861), st. 9]Ill fate destroyed me, and unstinted wine!

[tr. Bigge-Wither (1869)]An evil doom of some god was my bane, and wine out of measure.

[tr. Butcher/Lang (1879)]God's doom and wine unstinted on me the bane hath brought.

[tr. Morris (1887)]Heaven's cruel doom destroyed me, and excess of wine.

[tr. Palmer (1891)]It was all bad luck, and my own unspeakable drunkenness.

[tr. Butler (1898)]It was all bad luck of a daimôn, and my own unspeakable drunkenness.

[tr. Butler (1898), rev. Power/Nagy (1900)]It was all bad luck of a superhuman force [daimōn], and my own unspeakable drunkenness.

[tr. Butler (1898), rev. Kim/McCray/Nagy/Power (2018)]The harsh burden of some God sealed my doom, together with my own unspeakable excess in wine.

[tr. Lawrence (1932)]It was the malice of some evil power that was my undoing, and all the wine I swilled before I went to sleep in Circe’s palace.

[tr. Rieu (1946)]Bad luck shadowed me, and no kindly power;

ignoble death I drank with so much wine.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1961)]The evil will of the spirit and the wild wine bewildered me.

[tr. Lattimore (1965)]My undoing lay

in some god sending down my dismal fate

and in too much sweet wine.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1990)]The doom of an angry god, and god knows how much wine --

they were my ruin, captain.

[tr. Fagles (1996)]Bad luck and too much wine undid me.

[tr. Lombardo (2000)]The malicious decree of some god and too much wine were my undoing.

[tr. DCH Rieu (2002)]It was a god-sent evil destiny that ruined me, and too much wine.

[tr. Verity (2016)]But I had bad luck from some god, and too much wine befuddled me.

[tr. Wilson (2017)]Some god's ill-will undid me -- that, and too much wine!

[tr. Green (2018)]Some fatal deity

has brought me down -- that and too much wine.

[tr. Johnston (2019)]

BACCHUS, n. A convenient deity invented by the ancients as an excuse for getting drunk.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) American writer and journalist

“Bacchus,” The Cynic’s Word Book (1906)

(Source)

Included in The Devil's Dictionary (1911). Originally published in the "Devil's Dictionary" column in the San Francisco Wasp (1881-04-23).

Take counsel in wine, but resolve afterwards in water.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1733)

(Source)

One night the wine was singing in the bottles:

“Mankind, dear waif, I send to you, in spite

Of prisoning glass and rosy wax that throttles,

A song that’s full of brotherhood and light.”[Un soir, l’âme du vin chantait dans les bouteilles:

«Homme, vers toi je pousse, ô cher déshérité,

Sous ma prison de verre et mes cires vermeilles,

Un chant plein de lumière et de fraternité!»]Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) French poet, essayist, art critic

Les Fleurs du Mal [The Flowers of Evil], # 93 “L’Âme du vin [The Soul of Wine],” st. 1 (1857) [tr. Campbell (1952)]

(Source)

Also in the 1861 ed. (#104) and the 1868 ed. (#128). (Source (French)). Alternate translations:One eve in the bottle sang the soul of wine:

"Man, unto thee, dear disinherited,

I sing a song of love and light divine --

Prisoned in glass beneath my seals of red."

[tr. Sturm (1905)]One night, the soul of wine was singing in the flask:

"O man, dear disinherited! to you I sing

This song full of light and of brotherhood

From my prison of glass with its scarlet wax seals."

[tr. Aggeler (1954)][The Soul of Wine]

sang by night in its bottles: "Dear mankind,

dear and disinherited! Break the seal

of scarlet wax that darkens my glass jail,

and I shall bring you light and brotherhood!"

[tr. Howard (1982)]One evening the wine's soul sang in the bottles, "Man, dear disinherited Man, from my glass prison with its scarlet seals of wax I send you a song which is full of light and brotherhood."

[tr. Scarfe (1986)]One night, from bottles, sang the soul of wine:

"O misfit man, I send you for your good

Out of the glass and wax where I'm confined,

A melody of light and brotherhood!"

[tr. McGowan (1993)]

Come to think of it, I don’t know that love has a point, which is what makes it so glorious. Sex has a point, in terms of relief and, sometimes, procreation, but love, like all art, as Oscar said, is quite useless. It is the useless things that make life worth living and that make life dangerous too: wine, love, art, beauty. Without them life is safe, but not worth bothering with.

Stephen Fry (b. 1957) British actor, writer, comedian

Moab Is My Washpot, “Falling In,” ch. 6 (1997)

(Source)

Referencing Oscar Wilde from the preface of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890): "All art is quite useless".

You serve the best wine always, my dear sir,

And yet they say your wines are not so good.

They say you are four times a widower.

They say … A drink? I don’t believe I would.[Tu Setina quidem semper vel Massica ponis,

Papyle, sed rumor tam bona vina negat:

Diceris hac factus caelebs quater esse lagona.

Nec puto nec credo, Papyle, nec sitio.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 4, epigram 69 (4.69) (AD 89) [tr. Cunningham (1971)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:When I with thee, Cinna, doe die or sup,

Thou still do'st offer me they Gossips cup:

And though it savour well, and be well spiced,

Yet I to taste thereof am not enticed.

Now sith you needs will have me cause alledge,

While I straine curt'sie in that cup to pledge:

One said, thou mad'st that cup so hote of spice,

That it had made thee now a widower twice.

I will not say 'tis so, nor that I thinke it:

But good Sir, pardon me, I cannot drinke it.

[tr. Harington (1618), ep. 101; Book 2, ep. 5]Pure Massic wine thou does not only drink,

But giv'st thy guests: though some this do not think.

Four wives, 't is said, thy flagon caused to die;

This I believe not, yet not thirst to try.

[tr. Killigrew (1695)]With the best wines of France you entertain:

Yet that your wine is bad the world complain:

That you have lost four wives by it; but I

Neither believe it, Sir, -- nor am adry.

[tr. Hay (1755)]Thou Setian and Massic serv'st, Pamphilus, up:

But rumor thy wines has accurst.

A fourth time the wid'wer thou'rt hail'd by the cup:

I neither believe it, nor -- thirst.

[tr. Elphinston (1782)]You always, it is true, Pamphilus, place Setine wine, or Massic, on table; but rumour says that they are not so pure as they ought to be. You are reported to have been four times made a widower by the aid of your goblet. I do not think this, or believe it, Pamphilus; but I am not thirsty.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]On Massic and Setinian fares

The guest that banquets in your hall.

Yet, Papilus, report declares

Them not so wholesome after all.

'Tis said that by that wine-jar you

Four times became a widower. Thus

I neither think, nor hold it true,

Nor am I thirsty, Papilus.

[tr. Webb (1879)]You indeed put on your table always Setine or Massic, Papilus, but rumour says your wines are not so very good: you are said by means of this brand to have been made a widower four times. I don't think so, or believe it, Papilus, but -- I am not thirsty.

[tr. Ker (1919)]Setine and Massic at your board abound,

Yet some aver your wine is hardly sound;

’Twas this relieved you of four wives they say;

A libel -- but I will not dine to-day.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "A Doubtful Vintage"]Your butler prates of Setine and of Massic,

But scandal gives it titles not so classic.

"Four wives it's cost you." Gossip's never true,

But I'm not thirsty -- much obliged to you.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), Ep. 202]I see you do serve Massic wine

And even glorious Setian.

But rumor has it that they smack

A bit of that Venetian

Mixture that Lucretia served,

That four of your dear wives

On tasting those expensive labels

Promptly lost their lives.

It's all, I'm sure, a lot of talk,

Incredible, I think.

But thank you, no; I've got to go.

Besides, I do not drink.

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]You serve wine in the very best bottles, Papylus,

but they say the wine is not exactly the best,

they say you've become a widower four times now

thanks to those very bottles.

What a crock!

You know I wouldn't take stock

in a rumor like that, Papylus.

It's just that I'm not thirsty.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]You always serve Setine or Massic, Papylus, but rumor refuses us such excellent wines. This flask is said to have made you a widower four times over. I don't think so or believe so, Papylus, but -- I'm not thirsty.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]Pappus, they say your wine is not good,

it made you a widower four times.

I don't believe that. You're a civilised man.

Nevertheless, my thirst is suddenly gone.v [tr. Kennelly (2008), "A Civilised Man"]You always serve such fine wine, Papylus,

but rumor makes us pass it up. They say

this flask has widowed you four times. I don't

believe it -- but my thirst has gone away.

[tr. McLean (2014)]

He’s the one who gives us wine to ease our pain.

If you take wine away, love will die, and

every other source of human joy will follow.[τὴν παυσίλυπον ἄμπελον δοῦναι βροτοῖς.

οἴνου δὲ μηκέτ᾽ ὄντος οὐκ ἔστιν Κύπρις

οὐδ᾽ ἄλλο τερπνὸν οὐδὲν ἀνθρώποις ἔτι.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bacchæ [Βάκχαι], l. 772ff [First Messenger/Ἄγγελος] (405 BC) [tr. Woodruff (1999)]

(Source)

Speaking of Dionysus. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:He, the grape, that med'cine for our cares,

Bestow'd on favour'd mortals. Take away

The sparkling Wine, fair Venus smiles no more

And every pleasure quits the human race.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]He gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief. Without wine there is no longer Aphrodite or any other pleasant thing for men.

[tr. Buckley (1850)]He hath given the sorrow-soothing vine to man

For where wine is not love will never be,

Nor any other joy of human life.

[tr. Milman (1865)]He gives the soothing vine

Which stills the sorrow of the human heart;

Where wine is absent, love can never be;

Where wine is absent, other joys are gone.

[tr. Rogers (1872), l. 732ff]’Twas he that gave the vine to man, sorrow’s antidote. Take wine away and Cypris flies, and every other human joy is dead.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]He gave men the grief-assuaging vine.

When wine is no more found, then Love is not,

Nor any joy beside is left to men.

[tr. Way (1898)]This is he who first to man did give

The grief-assuaging vine. Oh, let him live;

For if he die, then Love herself is slain,

And nothing joyous in the world again!

[tr. Murray (1902)]It was he,

or so they say, who gave to mortal men

the gift of lovely wine by which our suffering

is stopped. And if there is no god of wine,

there is no love, no Aphrodite either,

nor other pleasures left to men.

[tr. Arrowsmith (1960)]They say that he

has given to men the vine that ends pain.

If wine were no more, then Cypris is no more

nor anything else delighted for mankind.

[tr. Kirk (1970)]It was he who gave men the gift of the vine as a cure for sorrow. And if there were no more wine, why, there's an end of love, and of every other pleasure in life.

[tr. Vellacott (1973)]Didn't he make us

Mortal men the gift of wine? If that is true

You have much to thank him for -- wine makes

Our labors bearable. Take wine away

And the world is without joy, tolerance, or love.

[tr. Soyinka (1973)]The sorrow-ceasing vine he gives to mortals.

Without wine there is no Aphrodite,

nor longer any other delight for men.

[tr. Neuburg (1988)]It was he,

so they say, who gave to us, poor mortals, the gift of wine,

that numbs all sorrows.

If wine should ever cease to be,

then so will love.

No pleasures left for men.

[tr. Cacoyannis (1982)]He himself, I hear them say,

Gave the pain-killing vine to men.

When wine is no more, neither is love.

Nor any other pleasure for mankind.

[tr. Blessington (1993)]He gave to mortals the vine that stops pain.

If there were no more wine, then there is no more Aphrodite

nor any other pleasure for mankind.

[tr. Esposito (1998)]It's he who gave

To mortals the vine that stops all suffering.

Adn if wine were to exist no longer, then

Neither would the goddess Aphrodite,

Nor anything of pleasure for us mortals.

[tr. Gibbons/Segal (2000), l. 885ff]He gave to mortals the vine that puts an end to pain. If there is no wine, there is no Aphrodite or any other pleasure for mortals.

[tr. Kovacs (2002)]Besides, he's given us the gift of wine,

Without which man desires nor endures not.

[tr. Teevan (2002)]He’s the god who brought the wine to the mortals. Great stuff that. It stops all sadness. Truth is, my Lord, when the wine is missing so does love and then… well, then there’s nothing sweet left for us mortals.

[tr. Theodoridis (2005)]He is the one who gave us the vine that gives

pause from pain; and if there is no wine, there'll be no more

Aphrodite, & there is no other gift to give such pleasure to us mortals.

[tr. Valerie (2005)]He gives to mortal human beings that vine which puts an end to human grief. Without wine, there's no more Aphrodite -- or any other pleasure left for men.

[tr. Johnston (2008)]He is great in so many ways -- not least, I hear say,

for his gift of wine to mortal men.

Wine, which puts an end to sorrow and to pain.

And if there is no wine, there is no Aphrodite,

And without her no pleasure left at all.

[tr. Robertson (2014)]When wine is gone, there is no more Cypris,

nor anything else to delight a mortal heart.

[tr. @sentantiq/Robinson (2015)]He gave mortals the pain-pausing vine.

When there is no wine, Cypris is absent,

And human beings have no other pleasure.

[tr. @sentantiq (2015)]I’ve heard he gave the grapevine to us mortals, as an end to pain.

And without wine, we’ve got no chance with Aphrodite. Or anything else good, for that matter.

[tr. Pauly (2019)]He even gives to mortals the grape that brings relief from cares. Without wine there is no longer Kypris or any other delightful thing for humans.

[tr. Buckley/Sens/Nagy (2020)]He gave mortals the pain-relieving vine.

But when there is no more wine, there is no Aphrodite

Nor any other pleasure left for human beings.

[tr. @sentantiq (2021)]

For me you mix Veientian,

While you take Massic wine:

I’d rather smell your goblet

Than to take a drink from mine.[Veientana mihi misces, ubi Massica potas:

Olfacere haec malo pocula, quam bibere.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 3, epigram 49 (3.49) (AD 87-88) [tr. Nixon (1911), “Let the Cup Pass”]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:You Massick drink, Veientan give to me.

I need not taste; the smell doth satisfie.

[tr. Wright (1663)]You mix Veientan wine for me, while you yourself drink Massic. I would rather smell the cups which you present me, than drink of them.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]You mix Veientan wine for me, whereas you drink Massic. I would rather smell these cups of mine than drink them.

[tr. Ker (1919)]Yourself you drink a vintage rare

While giving me vin ordinaire.

To smell the heel-taps of your wine

Is better far than drinking mine.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921), "The Mean Host"]You pour me cheap red wine while you drink Massic.

I'd rather sniff this cup than drink from it.

[tr. Bovie (1970)]You drink the best, yet serve us third-rate wine.

I'd rather sniff your cup than swill from mine.

[tr. Michie (1972)]You serve me plonk, and you drink reservé.

My taste-buds back away from mine’s bouquet.

[tr. Harrison (1981)]You mix Veientan for me and serve Massic for yourself. I had rather smell these cups than drink.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]Your cup breathes odors fine

That never came from mine.

Better is what you waft

Than what I'm forced to quaff.

[tr. Wills (2007)]You mix Veientan for me, while you drink Massic wine.

I'd rather smell your cups than drink from mine.

[tr. McLean (2014)]You pour me Blue Nun, while you drink Brunello wine.

I’d rather smell your glass, than take a sip from mine.

[tr. Ynys-Mon (2016)]

Let me explain, young man, the two blessings of human life.

Firstly Demeter, Mother Earth — call her what you will —

sustains us mortals with the gift of grain, of solid food.

But he who came next — son of Semele —

matched her gift to man: he brought us wine.

And wine brought peace to the troubled mind,

gave an end to grief, and gave us sleep — blessed sleep —

a forgetting of our sadness.[δύο γάρ, ὦ νεανία,

τὰ πρῶτ᾽ ἐν ἀνθρώποισι: Δημήτηρ θεά —

γῆ δ᾽ ἐστίν, ὄνομα δ᾽ ὁπότερον βούλῃ κάλει:

αὕτη μὲν ἐν ξηροῖσιν ἐκτρέφει βροτούς:

ὃς δ᾽ ἦλθ᾽ ἔπειτ᾽, ἀντίπαλον ὁ Σεμέλης γόνος

βότρυος ὑγρὸν πῶμ᾽ ηὗρε κεἰσηνέγκατο

280θνητοῖς, ὃ παύει τοὺς ταλαιπώρους βροτοὺς

λύπης, ὅταν πλησθῶσιν ἀμπέλου ῥοῆς,

ὕπνον τε λήθην τῶν καθ᾽ ἡμέραν κακῶν

δίδωσιν, οὐδ᾽ ἔστ᾽ ἄλλο φάρμακον πόνων.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bacchæ [Βάκχαι], l. 274ff [Tiresias/Τειρεσίας] (405 BC) [tr. Robertson (2014)]

(Source)

To Pentheus, discussing Dionysus. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:The two chief rulers of this nether world,

Proud boy, are Ceres, Goddess most benign,

Or Earth, (distinguish her by either name)

Who nourishes mankind with solid food:

Yet hath the son of Semele discover'd,

And introduc'd, the grape's delicious draught,

Which vies with her, which causes every grief

To cease among the wretched tribes of men,

With the enlivening beverage of the vine

Whenever they are fill'd; he also gives

Sleep, sweet oblivion to our daily cares,

Than which no medicine is with greater power

Endued to heal our anguish.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]For two things, young man, are first among men: the goddess Demeter -- she is the earth, but call her whatever name you wish; she nourishes mortals with dry food; but he who came afterwards, the offspring of Semele, discovered a match to it, the liquid drink of the grape, and introduced it to mortals. It releases wretched mortals from grief, whenever they are filled with the stream of the vine, and gives them sleep, a means of forgetting their daily troubles, nor is there another cure for hardships.

[tr. Buckley (1850)]Youth! there are two things

Man's primal need, Demeter, the boon Goddess

(Or rather will ye call her Mother Earth?),

With solid food maintains the race of man.

He, on the other hand, the son of Semele,

Found out the grape's rich juice, and taught us mortals

That which beguiles the miserable of mankind

Of sorrow, when they quaff the vine's rich stream.

Sleep too, and drowsy oblivion of care

He gives, all-healing medicine of our woes.

[tr. Milman (1865)]Two names, vain youth,

Rank first among mankind : Demeter one,

And Ge the other; give which name thou willest.

She nurtures man, but quenches not his thirst;

The son of Semele has helped this want:

He finds and grants to men the grape’s rich draught;

He takes away the woe of wearied souls,

Filling sad hearts with the vine’s ruddy stream;

And gives them sleep, the cure of daily grief,

The only drug which lightens human ills.

[tr. Rogers (1872), l. 262ff]Two things there are, young prince, that hold first rank among men, the goddess Demeter, that is, the earth, -- call her which name thou please; she it is that feedeth men with solid food; and as her counterpart came this god, the son of Semele, who discovered the juice of the grape and introduced it to mankind, stilling thereby each grief that mortals suffer from, soon as e’er they are filled with the juice of the vine; and sleep also he giveth, sleep that brings forgetfulness of daily ills, the sovereign charm for all our woe.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]Two chiefest Powers,

Prince, among men there are: divine Demeter --

Earth is she, name her by which name thou wilt; --

She upon dry food nurtureth mortal men:

Then followeth Semelê's Son; to match her gift

The cluster's flowing draught he found, and gave

To mortals, which gives rest from grief to men

Woe-worn, soon as the vine's stream filleth them.

And sleep, the oblivion of our daily ills,

He gives -- there is none other balm for toils.

[tr. Way (1898)]Young Prince, that in man's world are first of worth.

Dêmêtêr one is named; she is the Earth --

Call her which name thou will! -- who feeds man's frame

With sustenance of things dry. And that which came

Her work to perfect, second, is the Power

From Semelê born. He found the liquid shower

Hid in the grape. He rests man's spirit dim

From grieving, when the vine exalteth him.

He giveth sleep to sink the fretful day

In cool forgetting. Is there any way

With man's sore heart, save only to forget?

[tr. Murray (1902)]Mankind, young man, possesses two supreme blessings.

First of these is the goddess Demeter, or Earth

whichever name you choose to call her by.

It was she who gave to man his nourishment of grain.

But after her there came the son of Semele,

who matched her present by inventing liquid wine

as his gift to man. For filled with that good gift,

suffering mankind forgets its grief; from it

comes sleep; with it oblivion of the troubles

of the day. There is no other medicine

for misery.

[tr. Arrowsmith (1960)]For there are two things, young man,

that are first among humans: the goddess Demeter

(she is the earth; call her which name you like) --

she nourishes men by way of dry food;

and he who filled the complementary role, Semele's offspring,

discovered the grape-cluster's liquid drink and introduced it

to mortals, that which stops wretched men

from suffering, when they are filled with the stream of the vine,

and gives sleep as oblivion of the evils that happen by day;

nor is there any other cure against distress.

[tr. Kirk (1970)]There are two powers, young man, which are supreme in human affairs: first, the goddess Demeter, she is the Earth -- call her by what name you will; and she supplies mankind with solid food. Second, Dionysus the son of Semele; the blessing he provides is the counterpart to the blessing of bread; he discovered and bestowed on men the service of drink, the juice that streams from the vine-clusters; men have but to take their fill of wine, and the sufferings of an unhappy race are banished, each day's troubles are forgotten in sleep -- indeed this is our only cure for the weariness of life.

[tr. Vellacott (1973)]Think of two principles, two supreme

Principles in life. First, the principle

Of earth, Demeter, goddess of sil or what you will.

That nourishes man, yields him grain. Bread. Womb-like

It earths him as it were, anchors his feet.

Second, the opposite, and complementary principle --

Ether, locked in the grape until released by man.

For after Demeter came the son of Semele

And matched her present with the juice of grapes.

Think of it as more than drug for pain

Though it is that.

We wash our souls, our parched

Aching souls in streams of wine and enter

Sleep and oblivion. Filled with this good gift

Mankind forgets its grief.

[tr. Soyinka (1973)]Two things, my boy,

are primary for men: goddess Demeter

(that’s Earth, call her whichever name you like),

the nourisher of mortals in dry food;

next comes her rival, the child of Semele:

the cluster’s wet drink he found and introduced

to men, that stops poor mortals their distress

when they are filled to flowing with the vine,

giver of sleep, forgetfulness of daily ills,

[tr. Neuburg (1988)]Young man,

two are the forces most precious to mankind.

The first is Demeter, the Goddess.

She is the Earth -- or any name you wish to call her --

and she sustains humanity with solid food.

Next came the son of the virgin, Dionysus,

bringing the counterpart to bread, wine

and the blessings of life's flowing juices.

His blood, the blood of the grape,

lightens the burden of our mortal misery.

When, after their daily toils, men drink their fill,

sleep comes to them, bringing release form all their troubles.

There is no other cure for sorrow.

[tr. Cacoyannis (1982)]Two things, young man,

Are first among mankind: Demeter,

She's the Earth -- call her by either name --

Who nourishes mortals with dry food.

The other, who came after, the seed

Of Semele, discovered Demeter's wet rival,

The drink of the grap, brought it to man

To ease pain for suffering mortals,

When they are filled with the flowing vine,

And to give sleep, forgetful of daily life.

There is no other cure for pain.

[tr. Blessington (1993)]For there are two things, young man,

that are the primary elements among humans. First there’s the goddess Demeter.

She’s the earth But you can call her by whatever name you wish.

She nourishes mortals with dry foods. But he who came afterward,

Semele’s offspring, discovered the wet drink of the grape

as a counter-balance to Demeter’s bread. He introduced it

to mortals to stop their sorrow and pain.

Whenever men are filled with the stream of the grape-vine

they can sleep and forget the evils of the day.

No other medicine alleviates human suffering.

[tr. Esposito (1998)]Young man, there are two

first principles in human life: the goddess Demeter --

or earth -- you may use what name you like --

who nourishes us by means of the dry element;

and the second one balances her exactly, that’s

Semélê’s child, who discovered, in the wet element,

a drink from grapes, a drink he delivered to us.

This brings relief from pain for long-suffering mortals

when they are filled with the vineyard’s bounty;

it grants sleep, lets them forget the evils of the day,

and there is no other cure for trouble.

[tr. Woodruff (1999)]Young man -- there are two great first things that we

as mortals have: the goddess of the Earth,

Deméter -- call her by whatever name

You wish -- gave us our solid food, and he

Who came next, Semélê’s child, gave us liquid --

From the grape -- as a counterpart to Deméter's bread.

The god's invention, it give sus poor mortals

Release from pain and sorrow, when we're filled

With what flows from the vine; it gives us sleep,

When we can forget the evils of the day.

Nor for us mortals can another drug

For suffering surpass it.

[tr. Gibbons/Segal (2000), l. 321]Two things are chief among mortals, young man: the goddess Demeter -- she is Earth but call her either name you like -- nourishes mortals with dry food. But he who came next, the son of Semele, discovered as its counterpart the drink that flows from the grape cluster and introduced it to mortals. It is this that frees trouble-laden mortals from their pain -- when they fill themselves with the juice of the vine -- this that gives sleep to make one forget the day's troubles: there is no other treatment for misery.

[tr. Kovacs (2002)]There are two things in this world, young prince, that have been gifted to mankind. The first is the goddess Demeter or the earth, if you wish to call her so, or any other name you would give her, who feeds us mortals with solid food. The second is the son of Semele, who brought us the liquid hidden in the grape. This is no small gift, for when else can mortals loose the ties of their grief? It is wine -- that slips away the ragged robes of the day, sinking us into cool forgetting.

[tr. Rao/Wolf (2004)]There are two things, young man that are most important to people: It is goddess Demetre (call her by whatever other name you want) who feeds the folk on Earth and who IS Earth; and her counterpart, Dionysos, the son of Semele, this god, the god who discovered the juice of the grape and which he brought to us mortals. This liquid holds back the pain of the tortured soul, gives soft sleep to folk and lets them forget their daily suffering. There’s truly no better medicine for pain or fatigue.

[tr. Theodoridis (2005)]For there are two things, young one, two, that are

first among humans: One is the goddess Demeter --

and she is earth, call her whatever you will --

it is she who nourishes mortals in corn and grain;

but he who comes after, Semele's offspring, he invented them to match

the flowing drink of the grape and introduced it to mortals;

it gives wretched humans pause from pain when-

ever they are filled with the vine's stream,

and sleep, as aids to forget the troubles of the day:

there is no other drug that cures misery.

[tr. Valerie (2005)]Young man, among human beings two things stand out preeminent, of highest rank. Goddess Demeter is one -- she's the earth (though can call her any name you wish), and she feeds mortal people cereal grains. The other one came later, born of Semele -- he brought with him liquor from the grape, something to match the bread from Demeter. He introduced it among mortal men. When they can drink, up what streams off the vine, unhappy mortals are released from pain. It grants them sleep, allows them to forget their daily troubles. Apart from wine, there is no cure for human hardship.

[tr. Johnston (2008)]For there are two things, young man, two that are prized above all else by men. The first is the goddess Demeter, for she is the Earth. Call her whichever you prefer. It is she who brings forth solid food from the earth. Dry goods, if you will. But her junior, Semele’s child, showed us the other side of the coin, found the nectar in a bunch of grapes and gave it to mortals, letting them be free of pain when they partake of the river-of-the-vine. He gives us sleep, to forget the evils of the day for a time, and there is no better prescription for pain.

[tr. Pauly (2019)]But let me tell you there are two powers over us, sometimes called "the dry" and "the wet." The first is personified by the goddess Demeter or Earth -- whichever you wish to call her; she nourishes mortals with dry food, with bread. This new god, Semele's child, has come with a matching gift, a crystalline liquid from clustered grapes which he generously brought to end all human suffering. Wine fills the emptiness in the grieved heart and helps us forget in blissful sleep. Hsi is the only medicine to cure our pain.

[tr. Behr/Foster (2019)]Two things, young man, have supremacy among humans: The goddess Demeter -- she is the earth, but call her whatever name you wish -- nourishes mortals with dry food. But he who came then, the offspring of Semele, invented a rival, the wet drink of the grape, and introduced it to mortals. It releases wretched mortals from their pains, whenever they are filled with the stream of the vine, and gives them sleep, a means of forgetting their daily woes. There is no other cure for pains [ponoi].

[tr. Buckley/Sens/Nagy (2020)]

When once you see

the glint of wine shining at the feasts of women,

then you may be sure the festival is rotten.[γυναιξὶ γὰρ

ὅπου βότρυος ἐν δαιτὶ γίγνεται γάνος,

οὐχ ὑγιὲς οὐδὲν ἔτι λέγω τῶν ὀργίων.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bacchæ [Βάκχαι], l. 260ff [Pentheus/Πενθεύς] (405 BC) [tr. Arrowsmith (1960)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:For when women

Share at their feasts the grape's bewitching juice;

From their licentious orgies, I pronounce

No good results.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]For where women have the delight of the grape-cluster at a feast, I say that none of their rites is healthy any longer.

[tr. Buckley (1850)]For where ’mong women

The grape’s sweet poison mingles with the feast,

Nought holy may we augur of such worship.

[tr. Milman (1865)]When women drain the wine-cup at the feast,

Foul is the orgie, dangerous the disease.

[tr. Rogers (1872)]For where the gladsome grape is found at women’s feasts, I deny that their rites have any longer good results.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]For when

In women's feasts the cluster's pride hath part,

No good, say I, comes of their revelry.

[tr. Way (1898)]When once the gleam

Of grapes hath lit a Woman's Festival,

In all their prayers is no more health at all!

[tr. Murray (1902)]For where women

have the sparkle of the vine in their festivities,

there, I say, nothing wholesome remains in their rituals.

[tr. Kirk (1970)]As for women, my opinion is this: when the sparkle of sweet wine appears at their feasts, no good can be expected from their ceremonies.

[tr. Vellacott (1973)]I tell you, when women

have the cluster’s refreshment at banquets,

there’s nothing healthy left about their orgies.

[tr. Neuburg (1988)]Take my word,

when women are allowed to fast on wine, there is no

telling to what lengths their filthy minds will go!

[tr. Cacoyannis (1982)]I say that feast where a woman takes

The gleaming grape is most diseased.

[tr. Blessington (1993)]For whenever the liquid joy

of the grape comes into women's festivals, then, I assure, you,

there's nothing wholesome in their rites.

[tr. Esposito (1998)]Because when women

get their sparkle at a feast from wine,

I say the entire ritual is corrupt.

[tr. Woodruff (1999)]For when the women have

The bright grape-cluster gleaming at their feasts,

There’s nothing healthy in these rites, I say.

[tr. Gibbons/Segal (2000)]Wherever women get the gleaming grape to drink in their feasts, everything about their rites is diseased.

[tr. Kovacs (2002)]I’m telling you both, no good comes out of drunk women.

Wine wisdom and orgies are dangerous.

[tr. Theodoridis (2005)]For whenever the pleasure of the grape's

cluster comes shimmering to women in feast, I say no-

thing is left wholesome in their orgies!

[tr. Valerie (2005)]Whenever women at some banquet start to take pleasure in the gleaming wine, I say there's nothing healthy in their worship.

[tr. Johnston (2008)]It's always the same: as soon as you allow drink and women at a festival, everything gets sordid.

[tr. Robertson (2014)]When women start getting into the wine, I say it’s gone too far. It’s not healthy.

[tr. Pauly (2019)]There is no good in these festivals where shimmering wine corrupts women.

[tr. Behr/Foster (2019)]For where women have the delight of the grape at a feast, I say that none of their rites is healthy any longer.

[tr. Buckley/Sens/Nagy (2020)]

Stories of our women leaving home to frisk

in mock ecstasies among the thickets on the mountain,

dancing in honor of the latest divinity,

a certain Dionysus, whoever he may be!

In their midst stand bowls brimming with wine.

And then, one by one, the women wander off

to hidden nooks where they serve the lusts of men.

Priestesses of Bacchus they claim they are,

but it’s really Aphrodite they adore.[γυναῖκας ἡμῖν δώματ᾽ ἐκλελοιπέναι

πλασταῖσι βακχείαισιν, ἐν δὲ δασκίοις

ὄρεσι θοάζειν, τὸν νεωστὶ δαίμονα

Διόνυσον, ὅστις ἔστι, τιμώσας χοροῖς:

πλήρεις δὲ θιάσοις ἐν μέσοισιν ἑστάναι

κρατῆρας, ἄλλην δ᾽ ἄλλοσ᾽ εἰς ἐρημίαν

πτώσσουσαν εὐναῖς ἀρσένων ὑπηρετεῖν,

πρόφασιν μὲν ὡς δὴ μαινάδας θυοσκόους,

τὴν δ᾽ Ἀφροδίτην πρόσθ᾽ ἄγειν τοῦ Βακχίου.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bacchæ [Βάκχαι], l. 217ff [Pentheus/Πενθεύς] (405 BC) [tr. Arrowsmith (1960)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Their homes

Our women have deserted, on pretence

That they in mystic orgies are engaged;

On the umbrageous hills they chant the praise

Of this new God, whoe'er he be, this Bacchus;

Him in their dances they revere, and place

Amid their ranks huge goblets fraught with wine:

Some fly to pathless deserts, where they meet

Their paramours, while they in outward shew

Are Mænedes by holy rites engrossed.

Yet Venus more than Bacchus they revere.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]The women have left our homes in contrived Bacchic rites, and rush about in the shadowy mountains, honoring with dances this new deity Dionysus, whoever he is. I hear that mixing-bowls stand full in the midst of their assemblies, and that they each creep off different ways into secrecy to serve the beds of men, on the pretext that they are Maenads worshipping; but they consider Aphrodite before Bacchus.

[tr. Buckley (1850)]Our women all have left their homes, to join

These fabled mysteries. On the shadowy rocks

Frequent they sit, this God of yesterday,

Dionysus, whosoe'er he be, with revels

Dishonorable honoring. In the midst

Stand the crowned goblets; and each stealing forth,

This way and that, creeps to a lawless bed;

In pretext, holy sacrificing Mænads,

But serving Aphrodite more than Bacchus.

[tr. Milman (1865)]Our women have deserted from their homes,

Pretending Bacchic rites, and now they lurk

In the shady hill-tops reverencing forsooth

This Dionysus, this new deity.

Full bowls of wine are served out to the throng;

And scattered here and there through the glades,

The wantons hurry to licentious love.

They call themselves the priestess Mænades;

Bacchus invoke, but Aphrodite serve.

[tr. Rogers (1872), l. 200ff]I hear that our women-folk have left their homes on pretence of Bacchic rites, and on the wooded hills rush wildly to and fro, honouring in the dance this new god Dionysus, whoe’er he is; and in the midst of each revel-rout the brimming wine-bowl stands, and one by one they steal away to lonely spots to gratify their lust, pretending forsooth that they are Mænads bent on sacrifice, though it is Aphrodite they are placing before the Bacchic god.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]How from their homes our women have gone forth

Feigning a Bacchic rapture, and rove wild

O'er wooded hills, in dances honouring

Dionysus, this new God -- whoe'er he be.

And midst each revel-rout the wine-bowls stand

Brimmed: and to lonely nooks, some here, some there,

They steal, to work with men the deed of shame,

In pretext Maenad priestesses, forsooth,

But honouring Aphroditê more than Bacchus.

[tr. Way (1898)]Our own

Wives, our own sisters, from their hearths are flown

To wild and secret rites; and cluster there

High on the shadowy hills, with dance and prayer

To adore this new-made God, this Dionyse,

Whate'er he be! -- And in their companies

Deep wine-jars stand, and ever and anon

Away into the loneliness now one

Steals forth, and now a second, maid or dame,

Where love lies waiting, not of God! The flame,

They say, of Bacchios wraps them. Bacchios! Nay,

'Tis more to Aphrodite that they pray.

[tr. Murray (1902)]That our women have abandoned their homes

in fake bacchic revels, and in the deep-shaded

mountains are roaming around, honoring with dances

the new-made god Dionysus, whoever he is;

that wine-bowls are set among the sacred companies

full to the brim, and that one by one the women go crouching

into the wilderness, to serve the lechery of men --

they profess to be maenads making sacrifice,

but actually they put Aphrodite before the Bacchic god.

[tr. Kirk (1970)]Our women, I discover, have abandoned their homes on some pretence of Bacchic worship, and go gadding about in the woods on the mountain side, dancing in honour of this upstart god Dionysus, whoever he may be. They tell me, in the midst of each group of revellers stands a bowl full of wine; and the women go creeping off this way and that to lonely places and there give themselves to lecherous men, under the excuse that they are Maenad priestesses; though in their ritual Aphrodite comes before Bacchus.

[tr. Vellacott (1973)]They leave their home, desert their children

Follow the new fashion and join the Bacchae

Flee the hearth to mob the mountains -- those contain

Deep shadows of course, secret caves to hide

Lewd games for this new god -- Dionysos!

That's the holy spirit newly discovered.

Dionysos! Their ecstasy is flooded down

In brimming bowls of wine -- so much for piety!

Soused, with all the senses roused, they crawl

Into the bushes and there of course a man

Awaits them. All part of the service for for this

Mysterious deity. The hypocrisy? All they care about

Is getting serviced.

[tr. Soyinka (1973)]Our women gone, abandoning their homes,

pretending to be bacchae, massing

in the bushy mountains, this latest divinity

Dionysos (whoever he is) honouring and chorusing,

filling and setting amidst the thiasus

wine-bowls, and one by one in solitude

sneaking off to cater to male bidding, --

supposedly as sacrificial maenads,

but Aphrodite ranks before their Bacchic One.

[tr. Neuburg (1988)]Our women, I am told, have left their homes,

in a religious trance -- what travesty! --

and scamper up and down the wooded mountains, dancing

in honor of this newfangled God, Dionysus,

whoever he might be.

In the middle of each female group

of revelers, I hear,

stands a jar of wine, brimming! And that taking turns,

they steal away, one here, one there, to shady nooks,

where they satisfy the lechery of men,

pretending to be priestesses,

performing their religious duties. Ha!

That performance reeks more of Aphrodite than of Bacchus.

[tr. Cacoyannis (1982)]Our women have abandoned our homes

And, in a jacked-up frenzy of phony inspiration,

Riot in the dark mountains,

Honoring this upstart god, Dionysos --

Whatever he is -- dancing in his chorus.

Full jugs of wine stand in their midst

And each woman slinks off

To the wilderness to serve male lust,

Pretending they are praying priestesses,

But Aphrodite leads them, not Bacchus.

[tr. Blessington (1993)]Our women have abandoned their homes

for the sham revelries of Bacchus

frisking about on the dark-shadowed mountains

honoring with their dances the latest god, Dionysius, whoever he is.

They've set up their mixing bowls brimming with wine

amidst their cult gatherings, and each lady slinks off in a different direction

to some secluded wilderness to service the lusts of men.

They pretend to be maenads performing sacrifices

but in reality they rank Aphrodite's pleasures before Bacchus!

[tr. Esposito (1998)]These women of ours have left their homes

and run away to the dark mountains, pretending

to be Bacchants. It's this brand-new god,

Dionysus, whoever that is; they're dancing for him!

They gather in throngs around full bowls

of wine; then one by one they sneak away

to lonely places where they sleep with men.

Priestesses they call themselves! Maenads!

It's Aphrodite they put first, not Bacchus.

[tr. Woodruff (1999)]Women leave

Our houses for bogus revels (“Bakkhic” indeed!),

Dashing through the dark shade of mountain forests

To honor with their dancing this new god,

Dionysos -- whoever he may be --

And right in their midst they set full bowls of wine,

And slink into the thickets to meet men there,

Saying they are maenads sacrificing

When they really rank Aphrodite first,

Over Bakkhos!