Be temperate in wine, in eating, girls, and sloth;

Or the Gout will seize you and plague you both.Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1734 ed.)

(Source)

Quotations about:

drink

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Reader, had I the space to write at will,

I should, if only briefly, sing a praise

of that sweet draught. Would I were drinking still!

But I have filled all the pages planned

for this, my second, canticle, and Art

pulls at its iron bit with iron hand.[S’io avessi, lettor, più lungo spazio

da scrivere, i’ pur cantere’ in parte

lo dolce ber che mai non m’avria sazio;

ma perché piene son tutte le carte

ordite a questa cantica seconda,

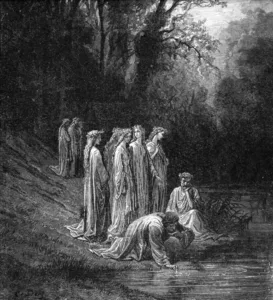

non mi lascia più ir lo fren de l’arte.]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 2 “Purgatorio,” Canto 33, l. 136ff (3.136-141) (1314) [tr. Ciardi (1961)]

(Source)

On drinking from the Eunoë, Dante gets meta, breaking the Fourth Wall and, having self-imposed limits on the number of cantos per book and lines in each canto, he uses "Art" as an excuse to draw toward a conclusion.

On the other hand, Sayers notes that Dante "is almost unique among medieval writers" in restraining his writing: "one of the reasons for his enduring readableness."

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:

If breath and vigour, by indulgent Heav'n,

To sing this bev'rage of the Gods were giv'n,

What holy rapture would exalt my Song!

To tell the unexhausted sweets that flow

From that blest Fountain o'er the Vale below.

And warm, with new desire, the votive Throng!

But now the Muse has run her fatal round,

And mark'd her Circle to the Second Bound.

[tr. Boyd (1802), st. 26-27]

Were further space allow’d,

Then, Reader, might I sing, though but in part,

That beverage, with whose sweetness I had ne’er

Been sated. But, since all the leaves are full,

Appointed for this second strain, mine art

With warning bridle checks me.

[tr. Cary (1814)]

Reader, had I but longer space to write,

I might describe to thee, in part, the taste

Of draught that's ever sweet, nor waste

The time; but leaves are all already full

Appointed for the second canticle,

Nor curb nor rein permit me use the will.

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]

If, Reader, I possessed a longer space

For writing it, I yet would sing in part

Of the sweet draught that ne'er would satiate me;

But inasmuch as full are all the leaves

Made ready for this second canticle,

The curb of art no farther lets me go.

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]

If I had, reader, longer space to write, I should sing, at all events in part, the sweet draught which never would have sated me; but, for that all the sheets put in frame for this second Canticle are full, the bridle of my art lets me go no further.

[tr. Butler (1885)]

Reader, if longer space to me were rated

For writing, I would strive to sing in part

That draught so sweet, which never could have sated.

But since is now completely filled the chart

Allotted for this second book, there leaves

No power to wander more the curb of Art.

[tr. Minchin (1885)]

If I had, Reader, longer space for writing I would yet partly sing the sweet draught which never would have sated me. But, because all the leaves destined for this second canticle are full, the curb of my art lets me go no further.

[tr. Norton (1892)]

If, reader, I had greater space for writing, I would sing, at least in part, of the sweet draught which never would have sated me;

but forasmuch as all the pages ordained for this second canticle are filled, the curb of art no further lets me go.

[tr. Okey (1901)]

If, reader, I had more space to write I should sing but in part the sweet draught which never would have sated me; but since all the sheets prepared for this second cantica are full the curb of art does not let me go farther.

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]

If, Reader, for the writing were more space,

That sweet fount, whence I ne'er could drink my fill,

Would I yet sing, though in imperfect praise.

But seeing that for this second canticle

The paper planned is full to the last page,

The bridle of art must needs constrain my will.

[tr. Binyon (1943)]

If for my writing, Reader, I'd more space,

I'd sing -- at least in part -- those sweets my heart

Might aye have drunk nor e'er known weariness;

But since I've filled the pages set apart

For this my second cantique, I'll pursue

No further, bridled by the curb of art.

[tr. Sayers (1955)]

If, reader, I had greater space for writing

I would yet partly sing the sweet draught

which never would have sated me.

but since all the pages ordained

for this second canticle are filled,

the curb of art lets me go no further.

[tr. Singleton (1973)]

Reader, if I had space to write more words,

I'd sing, at least in part, of that sweet draught

which never could have satisfied my thirst;

But now I have completed every page

planned for my poem's second canticle --

I am checked by the bridle of my art!

[tr. Musa (1981)]

If, reader, I had room to write more,

My poem could still not tell you everything

About the sweet drink of which I could never have had enough.

But since all the pages designed for this

Second part of the poem have been filled,

The rules of art stop me at this point.

[tr. Sisson (1981)]

If, reader, I had ampler space in which

to write, I'd sing -- though incompletely -- that

sweet draught for which my thirst was limitless;

but since all of the pages pre-disposed

for this, the second canticle, are full,

the curb of art will not let me continue.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1982)]

Reader, if I had more space to write, I would speak, partially at least, about that sweet drink, which would never have sated me: but because all the pages determined for the second Canticle are full, the curb of art lets me go no further.

[tr. Kline (2002)]

If, reader, I had more space to write, I would continue to sing in part the sweet drink that could never satiate me,

but because all the pages are filled that have been laid out for this second canticle, the bridle of art permits me to go no further.

[tr. Durling (2003)]

If, reader, I'd more space in which to write,

then I should sing in part about that drink,

so sweet I’d never have my fill of it.

However, since these pages now are full,

prepared by rights to take the second song,

the reins of art won't let me pass beyond.

[tr. Kirkpatrick (2007)]

If, reader, I had more ample space to write,

I should sing at least in part the sweetness

of the drink that never would have sated me,

but, since all the sheets

readied for this second canticle are full,

the curb of art lets me proceed no farther.

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]

O reader, if I had the space to tell you

More, I'd sing something about that sweetest

Drink, no quantity of which could ever

End my thirst, but because the pages meant

For this canto are already filled, my art prevents me,

Affirming limits I am forced to meet.

[tr. Raffel (2010)]

How little it takes to make life perfect! A good sauce, a cocktail after a hard day, a girl who kisses with her mouth half open!

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

A Little Book in C Major, ch. 4, § 21 (1916)

(Source)

A man can never have too much red wine, too many books, or too much ammunition.

Then they laughed and made good cheer, and either drank to other freely, and they thought never drink that ever they drank to other was so sweet nor so good. But by that their drink was in their bodies, they loved either other so well that never their love departed, for weal neither for woe. And thus it happed the love first betwixt Sir Tristram and La Beale Isoud, the which love never departed the days of their life.

Thomas Malory (c. 1415-1471) English writer

Le Morte d’Arthur, Book 8, ch. 24 (1485)

(Source)

Variant: "They both laughed and drank to each other; they had never tasted sweeter liquor in all their lives. And in that moment they fell so deeply in love that their hearts would never be divided. So the destiny of Tristram and Isolde was ordained." [ed. Ackroyd (2010)]

To confirm still more your piety and gratitude to Divine Providence, reflect upon the situation which it has given to the elbow. You see in animals, who are intended to drink the waters that flow upon the earth, that if they have long legs, they have also a long neck, so that they can get at their drink without kneeling down. But man, who was destined to drink wine, is framed in a manner that he may rise the glass to his mouth. If the elbow had been placed nearer the hand, the part in advance would have been too short to bring the glass up to the mouth; and if it had been nearer the shoulder, that part would have been so long that when it attempted to carry the wine to the mouth it would have overshot the mark, and gone beyond the head; thus, either way, we should have been in the case of Tantalus. But from the actual situation of the elbow, we are enabled to drink at our ease, the glass going directly to the mouth. Let us, then, with glass in hand, adore this benevolent wisdom; — let us adore and drink!

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Letter to the Abbé Morallet, Postscript (1779)

(Source)

When a Man’s exhausted, wine will build his strength.

[Ἀνδρὶ δὲ κεκμηῶτι μένος μέγα οἶνος ἀέξει.]

Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Iliad [Ἰλιάς], Book 6, l. 261 (6.261) (c. 750 BC) [tr. Fagles (1990), l. 310]

Alt. trans.

For to a man dismay’d

With careful spirits, or too much with labour overlaid,

Wine brings much rescue, strength'ning much the body and the mind.

[tr. Chapman (1611), ll. 274-76]

Then with a plenteous draught refresh thy soul,

And draw new spirits from the generous bowl.

[tr. Pope (1715-20)]

For wine is mighty to renew the strength

Of weary man.

[tr. Cowper (1791), ll. 318-19]

For to a wearied man wine greatly increases strength.

[tr. Buckley (1860)]

For great the strength

Which gen'rous wine imparts to men who toil.

[tr. Derby (1864), ll. 306-07]

When a man is awearied wine greatly maketh his strength to wax.

[tr. Leaf/Lang/Myers (1891)]

Wine gives a man fresh strength when he is wearied.

[tr. Butler (1898)]

When a man is spent with toil wine greatly maketh his strength to wax.

[tr. Murray (1924)]

In a tired man, wine will bring back his strength to its bigness.

[tr. Lattimore (1951)]

Wine will restore a man when he is weary as you are.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1974)]

When someone is fatigued, wine greatly increases his power.

[tr. Merrill (2007)]

You ought to get out of those wet clothes and into a dry martini.

Mae West (1892-1980) American film actress

Every Day’s a Holiday (movie) [Larmadou Graves] (1937)

West both starred in the film (as the recipient of this line, Peaches O'Day) and wrote the screenplay. Often attributed to Robert Benchley, who used the line in a film a few years later, and claimed he got it from a joke book. Also attributed to Groucho Marx.

The word Martini is a nostalgic passport to another era — when automobiles had curves like Mae West, when women were either ladies or dames, when men wore hats, when a deal was done on a handshake, when boxing and polo were regular pastimes, when we lived for movies instead of MTV, and when jazz was going from hot to cool. It was a time when a relationship was called either a romance or an affair, when love over a pitcher of Martinis was bigger than both of us, sweetheart, and it wouldn’t matter if the Russians dropped the bomb as long as the gin was wet and the vermouth was dry. That as Martini Culture.

Barnaby Conrad III (b. 1952) American author, artist, editor

The Martini: An Illustrated History of an American Classic, “The Great Martini Revival” (1995)

(Source)

Conrad reworked the passage in "Martini Madness" in Cigar Afficionado (Spring 1996):

The Martini is a cocktail distilled from the wink of a platinum blonde, the sweat of a polo horse, the blast of an ocean liner's horn, the Chrysler building at sunset, a lost Cole Porter tune, and the aftershave of quipping detectives in natty double-breasted suits. It's a nostalgic passport to another era -- when automobiles had curves like Mae West, when women were either ladies or dames, when men were gentlemen or cads, and when a "relationship" was true romance or a steamy affair. Films were called movies then, the music was going from le jazz hot in Paris to nightclub cool in Vegas, and when a deal was done on a handshake, the wise guy who welched soon had a date with a snub-nosed thirty-eight. Love might have ended in a world war, but a kiss was still a kiss, a smile was still a smile, and until they dropped the atomic bomb there was no need to worry, schweetheart, as long as the vermouth was dry and the gin was wet. That was Martini Culture.

A good martini, a good meal, a good cigar and a good woman … or a bad woman, depending on how much happiness you can stand.

George Burns (1896-1996) American comedian

Dr. Burns’ Prescription for Happiness, “Nine Definitions of Happiness” (1984)

(Source)

Wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging: and whosoever is deceived thereby is not wise.

The Bible (The Old Testament) (14th - 2nd C BC) Judeo-Christian sacred scripture [Tanakh, Hebrew Bible], incl. the Apocrypha (Deuterocanonicals)

Proverbs 20:1 [KJV (1611)]

(Source)

Alternate translations:

Wine is a luxurious thing, and drunkenness riotous: whosoever is delighted therewith shall not be wise.

[DRA (1899)]

Wine is reckless, strong drink quarrelsome; unwise is he whom it seduces.

[JB (1966)]

Drinking too much makes you loud and foolish. It's stupid to get drunk.

[GNT (1976)]

Wine is reckless, liquor rowdy; unwise is anyone whom it seduces.

[NJB (1985)]

Wine is a mocker; beer a carouser.

Those it leads astray won’t become wise.

[CEB (2011)]

Wine is a mocker and beer a brawler;

whoever is led astray by them is not wise.

[NIV (2011 ed.)]

Wine is a mocker, strong drink a brawler,

and whoever is led astray by it is not wise.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

Wine is a scoffer, strong drink a roisterer;

No one who is muddled by them will ever grow wise.

[RJPS (2023 ed.)]

“I hope that you did not give him anything, Mr Sanderson!”

“Of course I did, ma’am.”

“But he would only spend it on drink! You know what the working classes are!”

“Indeed, ma’am, and why should he not spend it on drink? Would you deprive the poor, whose lives are bad and miserable and comfortless enough, of the solace of a little relief from grinding poverty? A sordid, sodden relief perhaps, but would you be so heartless as to deny the poor even that pleasure in which all of us indulge at your generous expense?”

While I’m having these grim thoughts, I notice that my martini glass is nearly empty. It’s not a terribly endearing drink — it tastes like something that got hosed off a runway, then diluted with antifreeze — but it does what it says on the label.

LEFITT: Well, that didn’t work either.

BORAAN: It most certainly did not.

LEFITT: So, your next idea?

BORAAN: A drink, of course. Maize-oishka and water. Six parts water.

LEFITT: That seems rather weak.

BORAAN: Well, but one hundred parts oishka, do you see?

LEFITT: Ah. Yes, it is all clear to me now.— Miersen, Six Parts Water, Day Two, Act I, Scene 5

Every major industrialized nation has A BEER (you can’t be a Real Country unless you have A BEER and an airline — it helps if you have some kind of a football team, or some nuclear weapons, but at the very least you need A BEER).

Frank Zappa (1940-1993) American singer-songwriter

The Real Frank Zappa Book, ch. 12 “America Drinks & Goes Marching” (1989) [with Peter Occhiogrosso]

(Source)

More discussion of this quotation: You Can’t Be a Real Country Unless You Have a Beer and an Airline – Quote Investigator

Take a drink because you pity yourself, and then the drink pities you and has a drink, and then two good drinks get together and that calls for drinks all around. No; he’d have one drink, maybe a little bigger than usual, before he went to bed.

The Americans are a good-natured people, kindly, helpful to one another, disposed to take a charitable view even of wrongdoers […] Even a mob lynching a horse thief in the West has consideration for the criminal, and will give him a good drink of whiskey before he is strung up.

There’s no such thing as bad whiskey. Some whiskeys just happen to be better than others. But a man shouldn’t fool with booze until he’s fifty, and then he’s a damn fool if he doesn’t.

I like to have a martini,

Two at the very most.

After three I’m under the table,

After four I’m under my host.Dorothy Parker (1893-1967) American writer

(Spurious)

Variants:Frequently attributed to Parker (the main quatrain quoted is in The Collected Dorothy Parker), but originally an anonymous gag in found in the University of Virginia Harlequin (1959): "I wish I could drink like a lady. / 'Two or three,' at the most. / But two, and I'm under the table -- / And three, I'm under the host."

- "I'd love to have a martini, / Two at the very most. / With three I'm under the table, / With four I'm under my host."

- "I like to have a Martini / But only two at the most, / After three I'm under the table, / After four I'm under my host."

The confusion apparently comes from Bennett Cerf, Try and Stop Me (1944), where he related an anecdote in which Parker commented about a cocktail party, more straightforwardly, "Enjoyed it? One more drink and I'd have been under the host!" See here for more discussion.

And when people ask me why I’m so healthy, I say, “Plenty of red meat and gin!”

Julia Child (1912-2004) American chef and writer

Interview in The World: Journal of the Unitarian Universalist Assoc. (1992)

(Source)

On her 80th birthday. "Red meat and gin" was frequently mentioned by Child in interviews when asked either (a) her comfort foods or (b) the secret of her longevity. She does not seem to have used it in her writing.

Examples:

- Long life: Interview with Rena Pederson

- Long life: Quoted in the Minneapolis Star Tribune, requoted in Reader's Digest (1997-01)

- Confort food: Source

I believe in the gospel of Good Living. You can not make any god happy by fasting. Let us have good food, and let us have it well cooked — and it is a thousand times better to know how to cook than it is to understand any theology in the world.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

“What Must We Do to Be Saved?” Sec. 11 (1880)

(Source)

MACDUFF: What three things does drink especially provoke?

PORTER: Marry, sir, nose-painting, sleep, and urine. Lechery, sir, it provokes and unprovokes. It provokes the desire, but it takes away the performance. Therefore much drink may be said to be an equivocator with lechery. It makes him, and it mars him; it sets him on, and it takes him off; it persuades him and disheartens him; makes him stand to and not stand to; in conclusion, equivocates him in a sleep and, giving him the lie, leaves him.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Macbeth, Act 2, sc. 3, l. 27ff (2.3.27-38) (1606)

(Source)

Reflect upon your present blessings — of which every man has many — not on your past misfortunes, of which all men have some. Fill your glass again, with a merry face and contented heart. Our life on it, but your Christmas shall be merry, and your new year a happy one!

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) English writer and social critic

Sketches by Boz, “Characters,” ch. 2 “A Christmas Dinner” (1833-36)

(Source)