You seem to have great possessions! How else can this be, but that you have preferred your own enjoyment to the consolation of the many? For the more you abound in wealth, the more you lack in love.

[ἀλλὰ μὴν φαίνῃ ἔχων κτήματα πολλά. Πόθεν ταῦτα; ἢ δῆλον ὅτι τὴν οἰκείαν ἀπόλαυσιν προτι μοτέραν τῆς τῶν πολλῶν παραμυθίας ποιούμενος. Ὅσον οὖν πλεονάζεις τῷ πλούτῳ, τοσοῦτον ἐλλείπεις τῇ ἀγάπῃ.]

Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-378) Christian bishop, theologian, monasticist, Doctor of the Church [Saint Basil the Great, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας]

“To the Rich [Ὁμιλία πρὸς τοὺς πλουτούντας],” sermon (c. 368) [tr. Schroeder (2009)]

(Source)

In C. Paul Schroeder, ed., Saint Basil on Social Justice (2009).

Quotations about:

possessions

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

He does not possess Wealth, it possesses him.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1734 ed.)

(Source)

There are such things as to speak well, to speak easily, to speak correctly, and to speak seasonably. We offend against the last way of speaking if we mention a sumptuous entertainment we have just been present at before people who have not had enough to eat; if we boast of our good health before invalids; if we talk of our riches, our income, and our fine furniture to a man who has not so much as an income or a dwelling; in a word, if we speak of our prosperity before people who are wretched; such a conversation is too much for them, and the comparison which they then make between their condition and ours is very painful.

[Il y a parler bien, parler aisément, parler juste, parler à propos. C’est pécher contre ce dernier genre que de s’étendre sur un repas magnifique que l’on vient de faire, devant des gens qui sont réduits à épargner leur pain; de dire merveilles de sa santé devant des infirmes; d’entretenir de ses richesses, de ses revenus et de ses ameublements un homme qui n’a ni rentes ni domicile; en un mot, de parler de son bonheur devant des misérables: cette conversation est trop forte pour eux, et la comparaison qu’ils font alors de leur état au vôtre est odieuse.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 5 “Of Society and Conversation [De la Société et de la Conversation],” § 23 (5.23) (1688) [tr. Van Laun (1885)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:

Some men talk well, easily, justly, and to the purpose: those offend in the last kind, who speak of the Banquets they are to be at, before such as are reduc'd to spare their Bread; of sound Limbs, before the Infirm; of Demesnes and Revenues, before the Poor and Needy; of fine Houses and Furniture, before such as have neither Dwelling or Moveables: in a word, who speak of Prosperity, before the Miserable. This conversation is too strong for 'em, and the comparison you make between their condition and yours is odious.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]

There is speaking well, speaking easily, speaking justly, and speaking seasonably: 'Tis transgressing the last rule, to speak ofthe sumptuous Entertainments you have made, before such as are reduc'd to want of Bread; of a healthy Constitution of Body, before the Infirm; of Demesnes, Revenues and Furniture, before a Man who has neither Dwelling, Rents, nor Movables; in a word, to speak of your Prosperity before the Miserable: this Conversation is too strong from them, and the Comparison they make between their Condition and yours is odious.

[Curll ed. (1713)]

There is speaking well, speaking easily, speaking justly, and speaking seasonably: It is offending against the last, to speak of Entertainments before the Indigent; of sound Limbs and Health before the Infirm; of Houses and Lands before one who has not so much as a Dwelling; in a Word, to speak of your Prosperity before the Miserable; this Conversation is cruel, and the Comparison which naturally rises in them betwixt their Condition and yours is excruciating.

[Browne ed. (1752)]

There is a difference between speaking well, speaking easily, speaking with judgement and speaking opportunely. We fail in this last respect when we enlarge upon the splendid meal we have just enjoyed in front of people who have to be thrifty of their bread; or boast of our health in the presence of invalids; or talk about our wealth, our fortune and property to a man who has neither home nor income; in a word, when we speak of our happiness in front of those who are wretched; such conversation is too painful for them, and the comparison they are bound to make between your state and their own is intolerable.

[tr. Stewart (1970)]

You now can see, dear son, the short-lived pranks

that goods consigned to Fortune’s hand will play,

causing such squabbles in the human ranks.

For all the gold that lies beneath the moon —

or all that ever did lie there — would bring

no respite to these worn-out souls, not one.[Or puoi, figliuol, veder la corta buffa

d’i ben che son commessi a la fortuna,

per che l’umana gente si rabuffa;

ché tutto l’oro ch’è sotto la luna

e che già fu, di quest’anime stanche

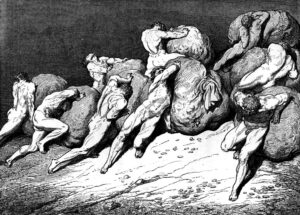

non poterebbe farne posare una.]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 1 “Inferno,” Canto 7, l. 61ff (7.61-66) [Virgil] (1309) [tr. Kirkpatrick (2006)]

(Source)

On the never-ending labor and contention between the hoarders and the wasters. (Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:

Therefore, my Son, the vanity you may

Of Fortune's gifts perceive, for which Mankind

Raise such a bustle, and so much contend.

Not all the Gold which is beneath the moon,

Or which was by these wretched Souls possess'd,

Could ever satisfy their craving minds.

[tr. Rogers (1782), l. 53ff]

Learn hence of mortal things how vain the boast,

Learn to despise the low, degen'rate host,

And see their wealth how poor, how mean their pride;

Not all the mines below the wand'ring moon,

Not all the sun beholds at highest noon,

Can for a moment bid the fray subside.

[tr. Boyd (1802), st. 11]

Now may’st thou see, my son! how brief, how vain,

The goods committed into fortune’s hands,

For which the human race keep such a coil!

Not all the gold, that is beneath the moon,

Or ever hath been, of these toil-worn souls

Might purchase rest for one.

[tr. Cary (1814)]

Now may'st thou, son, behold how brief the shuffle

Of goods by shifting Fortune held in store,

For which the human kind so fiercely ruffle:

Since all below the moon of golden ore

That lies, or all those weary souls possessed,

Could purchase none a moment's peace the more.

[tr. Dayman (1843)]

But thou, my Son, mayest [now] see the brief mockery of the goods that are committed unto Fortune, for which the human kind contend with each other.

For all the gold that is beneath the moon, or ever was, could not give rest to a single one of these weary souls.

[tr. Carlyle (1849)]

Now see, my son, how frivolous and vain

The goods committed unto Fortune's hand,

For which the race will so rebutting stand.

Not all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Nor all these toil-worn creatures have possessed,

could purchase for them but a moment's rest.

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]

And now, my son, behold the folly brief

of the world's goods to fortune's guidance given,

And for which men so struggle and dispute.

Not all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Or ever was, unto these wearied souls

Could give one hour of respite or of peace.

[tr. Johnston (1867)]

Now canst thou. Son, behold the transient farce

Of goods that are committed unto Fortune,

For which the human race each other buffet;

For all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Or ever has been, of these weary souls

Could never make a single one repose.

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]

Now canst thou, my son, see the short game of the goods which are entrusted to Fortune, for which the human race buffet each other. For all the gold that is beneath the moon and that ever was, of these wearied souls could never make one of them rest.

[tr. Butler (1885)]

Now thou canst see, O son, the short-lived day

Of good, committed unto Fortune's 'hest,

For which the human race so strives alway.

Since all the gold beneath the moon possest,

Or ever owned by those worn souls of yore,

Could not make one of them one moment rest.

[tr. Minchin (1885)]

Now canst thou, son, see the brief jest of the goods that are committed unto Fortune, for which the human race so scramble; for all the gold that is beneath the moon, or that ever was, of these weary souls could not make a single one repose.

[tr. Norton (1892)]

Here mayest thou see, my son, the fleeting mockery of wealth that is the sport of Fortune, for sake of which men strive with one another. For all the gold that is, or ever hath been beneath the moon, could not procure repose for one of these weary souls.

[tr. Sullivan (1893)]

Now canst thou see, my son, how vain and short-lived

Are the good things committed unto fortune,

For which sake human folk set on each other.

For all the gold on which the moon now rises,

Or ever rose, would be quite unavailing

To set one of these weary souls at quiet.

[tr. Griffith (1908)]

Now mayst thou see, my son, the brief mockery of wealth committed to fortune, for which the race of men embroil themselves; for all the gold that is beneath the moon, or ever was, could not give rest to one of these weary souls.

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]

Now, my son, see to what a mock are brought

The goods of Fortune's keeping, and how soon!

Though to possess them still is all man's thought.

For all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Or ever was, never could buy repose

For one of those souls, faint to have that boon.

[tr. Binyon (1943)]

See now, my son, the fine and fleeting mock

Of all those goods men wrangle for -- the boon

That is delivered into the hand of Luck;

For all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Or ever was, could not avail to buy

Repose for one of these weary souls -- not one.

[tr. Sayers (1949)]

Now may you see the fleeting vanity

of the goods of Fortune for which men tear down

all that they are, to build a mockery.

Not all the gold that is or ever was

under the sky could buy for one of these

exhausted souls the fraction of a pause.

[tr. Ciardi (1954)]

Now you can see, my son, the brief mockery of the goods that are committed to Fortune, for which humankind contend with one another; because all the gold that is beneath the moon, or ever was, would not give rest to a single one of these weary souls.

[tr. Singleton (1970)]

You see, my son, the short-lived mockery

of all the wealth that is in Fortune's keep,

over which the human race is bickering;

for all the gold that is or ever was

beneath the moon won't buy a moment's rest

for even one among these weary souls.

[tr. Musa (1971)]

Now you can see, my son, how brief's the sport

of all those goods that are in Fortune's care,

for which the tribe of men contend and brawl;

for all the gold that is or ever was

beneath the moon could never offer rest

to even one of these exhausted spirits.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1980)]

Now you can see, my son, how short a life

Have the gifts which are distributed by Fortune,

And for which people get rough with one another:

So that all the gold there is beneath the moon

And all there ever was, could never give

A moment's rest to one of these tired souls.

[tr. Sisson (1981)]

Now you can see, my son, how ludicrous

And brief are all the goods in Fortune's ken,

Which humankind contend for: you see from this

How all the gold there is beneath the moon,

Or that there ever was, could not relieve

One of these weary souls.

[tr. Pinsky (1994), l. 55ff]

Now you can see, my son, the brief mockery of the goods that are committed to Fortune, for which the human race so squabbles;

for all the gold that is under the moon and that ever was, could not give rest to even one of these weary souls.

[tr. Durling (1996)]

But you, my son, can see now the vain mockery of the wealth controlled by Fortune, for which the human race fight with each other, since all the gold under the moon, that ever was, could not give peace to one of these weary souls.

[tr. Kline (2002)]

Now you see, my son, what brief mockery

Fortune makes of goods we trust her with,

for which the race of men embroil themselves.

All the gold that lies beneath the moon,

or ever did, could never give a moment's rest

to any of these wearied souls.

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]

Now see, my son, the futile mockery

Of spending a life accumulating possessions,

Competing with fortune and men for worthless frippery:

Take all the gold still lying under the moon,

Add all that ever was and you could not buy

A moment of rest for one of these souls -- not one.

[tr. Raffel (2010)]

You see it clear,

My son: the squalid fraud as brief as life

Of goods consigned to Fortune, whereupon

Cool heads come to the boil, hands to the knife.

For all the gold there is, and all that's gone,

Would give no shred of peace to even one

Of these drained souls.

[tr. James (2013), l. 56ff]

Remember that we can own only what we can assimilate and appreciate, no more. Many wealthy people are little more than janitors of their possessions.

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) American architect, interior designer, writer, educator [b. Frank Lincoln Wright]

On Architecture: Selected Writings (1894-1940) (1941)

(Source)

Earthly possessions dazzle our eyes and delude us into thinking that they can provide security and freedom from anxiety. Yet all the time they are the very source of anxiety. If our hearts are set on them, our reward is an anxiety whose burden is intolerable. Anxiety creates its own treasures, and they in turn beget further care. When we seek for security in possessions, we are trying to drive out care with care, and the net result is the precise opposite of our anticipations. The fetters that bind us to our possessions prove to be the cares themselves.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) German Lutheran pastor, theologian, martyr

The Cost of Discipleship, Part 2, ch. 16 (1959)

(Source)

Men may be divided almost any way we please, but I have found the most useful distinction to be made between those who devote their lives to conjugating the verb “to be” and those who spend their lives conjugating the verb “to have.”

Sydney J. Harris (1917-1986) Anglo-American columnist, journalist, author

For the Time Being, ch. 6, epigram (1972)

(Source)

No man can tell whether he is rich or poor by turning to his ledger. It is the heart that makes a man rich. He is rich or poor according to what he is, not according to what he has.

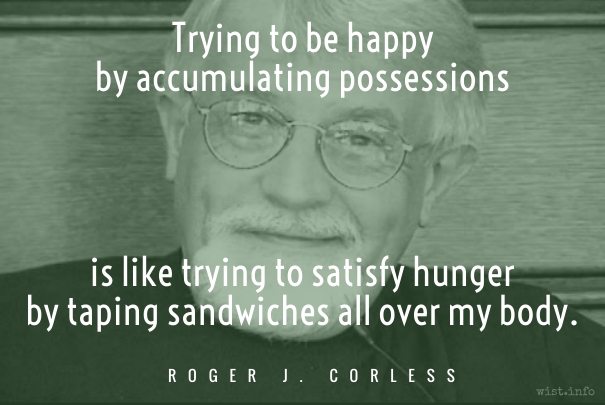

We make ourselves miserable by first closing ourselves off from reality and then collecting this and that in an attempt to make ourselves happy by possessing happiness. But happiness is not something I have, it is something I myself want to be. Trying to be happy by accumulating possessions is like trying to satisfy hunger by taping sandwiches all over my body.

Want is a growing giant whom the coat of Have was never large enough to cover.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“Wealth,” The Conduct of Life, ch. 3 (1860)

(Source)

If money be not thy servant, it will be thy master. The covetous man cannot so properly be said to possess wealth, as that may be said to possess him.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

(Attributed)

Attributed to Bacon in Alexander Anderson, Laconics: or Instructive Miscellanies, (1827). Attributed to French moralist Pierre Charron (1541-1603) in John Timbs, Laconics: Or, The Best Words of the Best Authors (1829). See also French saying.

Possessions possess.

Paul Eldridge (1888-1982) American educator, novelist, poet

Maxims for a Modern Man, #2781 (1965)

(Source)

Fetters of Gold are still Fetters; and silken Cords pinch.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs, #1522 (1732)

(Source)

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken away from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

Viktor Frankl (1905-1997) German-American psychologist, writer

Man’s Search for Meaning, Part 1 (1959)

(Source)