Love, such as it exists in high society, is merely an exchange of whims and the contact of skins.

[L’amour, tel qu’il existe dans la société, n’est que l’échange de deux fantaisies et le contact de deux épidermes.]

Nicolas Chamfort (1741-1794) French writer, epigrammist (b. Nicolas-Sébastien Roch)

Products of Perfected Civilization [Produits de la Civilisation Perfectionée], Part 1 “Maxims and Thoughts [Maximes et Pensées],” ch. 6, ¶ 359 (1795) [tr. Dusinberre (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Love as it exists in society is nothing more than the exchange of two fancies and the contact of two epidermes.

[tr. Hutchinson (1902)]Love, as it s practiced in Society, is nothing but the exchange of two caprices and the contact of two skins.

[tr. Mathers (1926)]Love as it exists in society is merely the mingling of two fantasies and the contact of two skins.

[tr. Merwin (1969)]Love as it exists in society is only the exchange of two fantasies and the contact of two epidermises.

[tr. Sinicalchi]

Quotations about:

upper class

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

But the rich man is tortured by fears, wasted with griefs, aflame with greed, never free from care, always restless and uneasy, out of breath from unending struggles with his enemies. It is true enough that he increases his holdings beyond measure by going through these miseries; but at the same time, thanks to that very increase, he also multiples his bitter cares. In contrast, the individual of moderate means is satisfied with his small and limited property; he is loved by family and friends; he enjoys sweet peace with his relations, neighbors, and friends; he is devout in his piety, benevolent of mind, sound of body, moderate in his style of life, unblemished in character, and untroubled in conscience. I do not know whether anyone would be so foolish as to have any doubt about which of the two to prefer.

[Alium praediuitem cogitemus; sed diuitem timoribus anxium, maeroribus tabescentem, cupiditate flagrantem, numquam securum, semper inquietum, perpetuis inimicitiarum contentionibus anhelantem, augentem sane his miseriis patrimonium suum in inmensum modum atque illis augmentis curas quoque amarissimas aggerantem; mediocrem uero illum re familiari parua atque succincta sibi sufficientem, carissimum suis, cum cognatis uicinis amicis dulcissima pace gaudentem, pietate religiosum, benignum mente, sanum corpore, uita parcum, moribus castum, conscientia securum. Nescio utrum quisquam ita desipiat, ut audeat dubitare quem praeferat.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

City of God [De Civitate Dei], Book 4, ch. 3 (4.3) (AD 412-416) [tr. Babcock (2012)]

(Source)

On wealth and power as the foundation for happiness.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Let my wealthy man take with him fears, sorrows, covetousness, suspicion, disquiet, contentions, making immense additions to his estate only by adding to his heap of most bitter cares; and let my poor man take with him sufficiency with little, love of kindred, neighbours, friends, joyous peace, peaceful religion, soundness of body, sincereness of heart, abstinence of diet, chastity of carriage, and security of conscience. Where should a man find any one so sottish as would make a doubt which of these to prefer in his choice?

[tr. Healey (1610)]But the rich man is anxious with fears, pining with discontent, burning with covetousness, never secure, always uneasy, panting from the perpetual strife of his enemies, adding to his patrimony indeed by these miseries to an immense degree, and by these additions also heaping up most bitter cares. But that other man of moderate wealth is contented with a small and compact estate, most dear to his own family, enjoying the sweetest peace with his kindred neighbors and friends, in piety religious, benignant in mind, healthy in body, in life frugal, in manners chaste, in conscience secure. I know not whether any one can be such a fool, that he dare hesitate which to prefer.

[ed. Dods (1871)]But, our wealthy man is haunted by fear, heavy with cares, feverish with greed, never secure, always restless, breathless from endless quarrels with his enemies. By these miseries, he adds to his possessions beyond measure, but he also piles up for himself a mountain of distressing worries. The man of modest means is content with a small and compact patrimony. He is loved by his own, enjoys the sweetness of peace, in his relations with kindred, neighbors, and friends, is religious and pious, of kindly disposition, healthy in body, self-restrained, chaste in morals, and at peace with his conscience. I wonder if there is anyone so senseless as to hesitate over which of the two to prefer.

[tr. Zema/Walsh (1950)]Let us suppose that the rich man is troubled by fears, pining with grief, burning with desire, never secure, always restless, panting in ceaseless struggles with his foes, though he does, to be sure, by dint of such suffering accumulate great additions to his estate even beyond measure, these additions adding also their quota of corrosive anxieties. Let the man of modest means, on the other hand, be self-sufficient on his trim and tiny property, beloved by his family, enjoying the most agreeable relations with his kindred, neighbours and friends, devoutly religious, kindly disposed, in good physical condition, leading a simple life, free from vice and untroubled in conscience. I don’t suppose that there is anyone so foolish as to think of doubting which one he would prefer.

[tr. Green (Loeb) (1963)]But the rich man is tortured by fears, worn out with sadness, burnt up with ambition, never knowing serenity of repose, always panting and sweating in his struggles with opponents. It may be true that he enormously swells his patrimony, but at the cost of those discontents, while by this increase he heaps up a load of further anxiety and bitterness. The other man, the ordinary citizen, is content with his strictly limited resources. He is loved by family and friends; he enjoys the blessing of peace with his relations, neighbours, and friends; he is loyal, compassionate, and kind, healthy in body, temperate in habits, of unblemished character, and enjoys the serenity of a good conscience. I do not think anyone would be fool enough to hesitate about which he would prefer.

[tr. Bettenson (1972)]The wealthy man, however, is troubled by fears; he pines with grief; he burns with greed. He is never secure; he is always unquiet and panting from endless confrontations with his enemies. To be sure, he adds to his patrimony in immense measure by these miseries; but alongside these additions he also heaps up the most bitter cares. By contrast, the man of moderate means is self-sufficient on his small and circumscribed estate. He is of his own family, and rejoices in the most sweet peace with kindred, neighbours and friends. He is devoutly religious, well disposed in mind, healthy in body, frugal in life, chaste in morals, untroubled in conscience. I do not know if anyone could be such a fool as to dare to doubt which to prefer.

[tr. Dyson (1998)]

It was crowded in the Curry Gardens on the corner of God Street and Blood Alley, but only with the cream of society — at least, with those people who are found floating on the top and who, therefore, it’s wisest to call the cream.

Again, it is proper to the magnanimous person to ask for nothing, or hardly anything, but to help eagerly. When he meets people with good fortune or a reputation for worth, he displays his greatness, since superiority over them is difficult and impressive, and there is nothing ignoble in trying to be impressive with them. But when he meets ordinary people, he is moderate, since superiority over them is easy, and an attempt to be impressive among inferiors is as vulgar as a display of strength against the weak.

[μεγαλοψύχου δὲ καὶ τὸ μηδενὸς δεῖσθαι ἢ μόλις, ὑπηρετεῖν δὲ προθύμως, καὶ πρὸς μὲν τοὺς ἐν ἀξιώματι καὶ εὐτυχίαις μέγαν εἶναι, πρὸς δὲ τοὺς μέσους μέτριον: τῶν μὲν γὰρ ὑπερέχειν χαλεπὸν καὶ σεμνόν, τῶν δὲ ῥᾴδιον, καὶ ἐπ᾽ ἐκείνοις μὲν σεμνύνεσθαι οὐκ ἀγεννές, ἐν δὲ τοῖς ταπεινοῖς φορτικόν, ὥσπερ εἰς τοὺς ἀσθενεῖς ἰσχυρίζεσθαι.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Nicomachean Ethics [Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια], Book 4, ch. 3 (4.3.26) / 1124b.18 (c. 325 BC) [tr. Irwin (1999)]

(Source)

The core word Aristotle is using is μεγαλοψυχία (translated variously as high-mindedness, great-mindedness, pride, great-soulness, magnanimity). (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Further, it is characteristic of the Great-minded man to ask favours not at all, or very reluctantly, but to do a service very readily; and to bear himself loftily towards the great or fortunate, but towards people of middle station affably; because to be above the former is difficult and so a grand thing, but to be above the latter is easy; and to be high and mighty towards the former is not ignoble, but to do it towards those of humble station would be low and vulgar; it would be like parading strength against the weak.

[tr. Chase (1847)]It would seem, too, that the high-minded man asks favours of no one, or, at any rate, asks them with the greatest reluctance, but that he is always eager to do good offices to others; and that towards those in high position and prosperity he bears himself with pride, but towards ordinary men with moderation; for in the former case it is difficult to show superiority, and to do so is a lordly mater; whereas in the latter case it is easy. To be haughty among the great is no proof of bad breeding, but haughtiness among the lowly is as base-born a thing as it is to make trial of great strength upon the weak.

[tr. Williams (1869)]It is characteristic too of the high-minded man that he never, or hardly ever, asks a favor, that he is ready to do anybody a service, and that, although his bearing is stately towards person of dignity and affluence, it is unassuming toward the middle class; for while it is a difficult and dignified thing to be superior to the former, it is easy enough to be superior to the latter, and while a dignified demeanour in dealing with the former is a mark of nobility, it is a mark of vulgarity ind ealing with the latter, as it like a display of physical strength at the expense of an invalid.

[tr. Welldon (1892), ch. 8]It is characteristic of the high-minded man, again, never or reluctantly to ask favours, but to be ready to confer them, and to be lofty in his behaviour to those who are high in station and favoured by fortune, but affable to those of the middle ranks; for it is a difficult thing and a dignified thing to assert superiority over the former, but easy to assert it over the latter. A haughty demeanour in dealing with the great is quite consistent with good breeding, but in dealing with those of low estate is brutal, like showing off one’s strength upon a cripple.

[tr. Peters (1893)]It is a mark of the proud man also to ask for nothing or scarcely anything, but to give help readily, and to be dignified towards people who enjoy high position and good fortune, but unassuming towards those of the middle class; for it is a difficult and lofty thing to be superior to the former, but easy to be so to the latter, and a lofty bearing over the former is no mark of ill-breeding, but among humble people it is as vulgar as a display of strength against the weak.

[tr. Ross (1908)]It is also characteristic of the great-souled man never to ask help from others, or only with reluctance, but to render aid willingly; and to be haughty towards men of position and fortune, but courteous towards those of moderate station, because it is difficult and distinguished to be superior to the great, but easy to outdo the lowly, and to adopt a high manner with the former is not ill-bred, but it is vulgar to lord it over humble people: it is like putting forth one's strength against the weak.

[tr. Rackham (1934)]It is also characteristic of a great-souled person to ask for nothing or hardly anything but to offer his services eagerly, and to exhibit his greatness to those with a reputation for great worth or those who are enjoying good luck, but to moderate his greatness to those in the middle. For it is a difficult and a dignified thing to show oneself superior to the former, but an easy one to do so to the latter, and, while adopting a dignified manner toward the former is not ill-bred, to do so toward humble people is vulgar, like displaying strength against the weak.

[tr. Reeve (1948)]It is the mark of a high-minded man, too, never, or hardly ever, to ask for help, but to be of help to others readily, and to be dignified with men of high position or of good fortune, but unassuming with those of middle class, for it is difficult and impressive to be superior to the former, but easy to be so to the latter; and whereas being impressive to the former is not a mark of a lowly man, being so to the humble is crude -- it is like using physical force against the physically weak.

[tr. Apostle (1975)]Another mark of the magnanimous man is that he never, or only reluctantly, makes a request, whereas he is eager to help others. He his haughty toward those who are influential and successful, but moderate toward those who have an intermediate position in society, because in the former case to be superior is difficult and impressive, but in the latter it is easy' and to create an impression at the expense of the former is not ill-bred, but to do so among the humble is vulgar.

[tr. Thomson/Tredennick (1976)]It is also characteristic of a great-souled person to ask for nothing, or almost nothing, but to help others readily; and to be dignified in his behavior towards people of distinction or the well-off, but unassuming toward people at the middle level. Superiority over the first group is difficult and impressive, but over the second it is easy, and attempting to impress the first group is not ill-bred, while in the case of humble people it is vulgar, like a show of strength against the weak.

[tr. Crisp (2000)]It belongs to the great-souled also to need nothing, or scarcely anything, but to be eager to be of service, and to be great in the presence of people of worth and good fortune, but measured toward those of a middling rank. For it is a difficult and august thing to be superior among the fortunate, but easy to be that way among the middling sorts; and to exalt oneself among the former is not a lowborn thing, but to do so among the latter is crude, just as is using one's strength against the weak.

[tr. Bartlett/Collins (2011)]

Sometimes paraphrased:It is not ill-bred to adopt a high manner with the great and the powerful, but it is vulgar to lord it over humble people.

When people ask, “Why should the rich pay a larger percent of their income than middle-income people?” — my answer is not an answer most people get: It’s because their power developed from laws that enriched them.

A stranger to human nature, who saw the indifference of men about the misery of their inferiors, and the regret and indignation which they feel for the misfortunes and sufferings of those above them, would be apt to imagine that pain must be more agonizing, and the convulsions of death more terrible, to people of higher rank than to those of meaner stations.

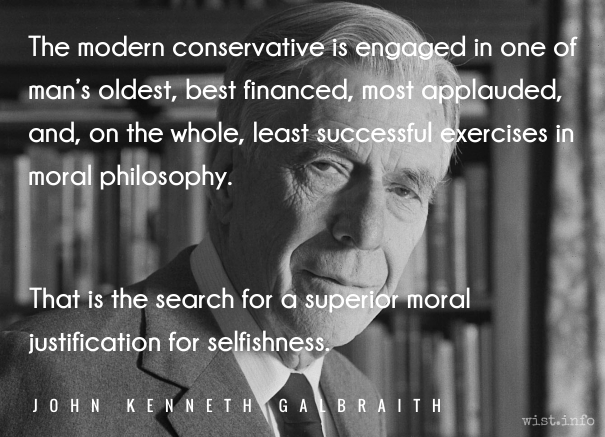

The modern conservative is not even especially modern. He is engaged, on the contrary, in one of man’s oldest, best financed, most applauded, and, on the whole, least successful exercises in moral philosophy. That is the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness. It is an exercise which always involves a certain number of internal contradictions and even a few absurdities. The conspicuously wealthy turn up urging the character-building value of privation for the poor. The man who has struck it rich in minerals, oil, or other bounties of nature is found explaining the debilitating effect of unearned income from the state. The corporate executive who is a superlative success as an organization man weighs in on the evils of bureaucracy. Federal aid to education is feared by those who live in suburbs that could easily forgo this danger, and by people whose children are in public schools. Socialized medicine is condemned by men emerging from Walter Reed Hospital. Social Security is viewed with alarm by those who have the comfortable cushion of an inherited income. Those who are immediately threatened by public efforts to meet their needs — whether widows, small farmers, hospitalized veterans, or the unemployed — are almost always oblivious to the danger.

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908-2006) Canadian-American economist, diplomat, author

Speech (1963-12-13), “Wealth and Poverty,” National Policy Committee on Pockets of Poverty

(Source)

Galbraith used variations on this quote over the years.

- The above quotation was from a speech given, that was then entered into the Congressional Record, Vol. 109, Senate (1963-12-18).

- This material was reworked into an article "Let us begin: An invitation to action on poverty," in Harper's (1964-03), which was in turn again entered into the Congressional Record, Vol. 110 (1964).

- One of the last is most often cited: "The modern conservative is engaged in one of man’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy, that is the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness. It is an exercise which always involves a certain number of internal contradictions and even a few absurdities. The conspicuously wealthy turn up urging the character-building value of privation for the poor." ["Stop the Madness," Interview with Rupert Cornwell, Toronto Globe and Mail (2002-07-06)]