Custom is the law of one description of fools, and fashion of another; but the two parties often clash; for precedent is the legislator of the first, and novelty of the last.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon: Or, Many Things in Few Words, Vol. 1, § 547 (1820)

(Source)

Quotations about:

novelty

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Gradually we become tired of the old, of what we safely possess, and we stretch out our hands again. Even the most beautiful scenery is no longer assured of our love after we have lived in it for three months, and some more distant coast attracts our avarice: possessions are generally diminished by possession.

[Wir werden des Alten, sicher Besessenen allmählich überdrüssig und strecken die Hände wieder aus; selbst die schönste Landschaft, in der wir drei Monate leben, ist unserer Liebe nicht mehr gewiss, und irgend eine fernere Küste reizt unsere Habsucht an: der Besitz wird durch das Besitzen zumeist geringer.]Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) German philosopher and poet

The Gay Science [Die fröhliche Wissenschaft], Book 1, § 14 (1882) [tr. Kaufmann (1974)]

(Source)

Also known as La Gaya Scienza, The Joyful Wisdom, or The Joyous Science.

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:We gradually become satiated with the old, the securely possessed, and again stretch out our hands; even the finest landscape in which we live for three months is no longer certain of our love, and any kind of more distant coast excites our covetousness: the possession for the most part becomes smaller through possessing.

[tr. Common (1911)]We slowly grow tired of the old, of what we safely possess, and we stretch our our hands again; even the most beautiful landscape is no longer sure of our love after we have lived in it for three months, and some more distant coast excites our greed: possession usually diminishes the possession.

[tr. Nauckhoff (2001)]We gradually grow weary of the old, familiar things we securely hold, and again stretch forth our hands; even the most beautiful landscape lived in for three months is no longer assured of our love, and some more distant shore excites our avarice: what is had loses much in the having.

[tr. Hill (2018)]

We all git tired pretty soon looking at a goose standing on one leg.

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 155 “Affurisms: Ink Lings” (1874)

(Source)

The surprising surprises once; but the admirable is admired more and more.

[Ce qui étonne, étonne une fois; mais ce qui est admirable est de plus en plus admiré.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 23 “Des Qualités de l’Écrivain [Of the Qualities of Writers]” ¶ 164 (1850 ed.) [tr. Lyttelton (1899), ch. 22, ¶ 77]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:What astonishes astonishes once, but what is admirable is more and more admired.

[tr. Calvert (1866), ch. 15]That which astonishes, astonishes once; but whatever is admirable becomes more and more admired.

[tr. Attwell (1896), ¶ 370]The surprising astonishes once; but the admirable is admired more and more.

[tr. Collins (1928), ch. 22]

Everything has been said, and we have come too late, now that men have been living and thinking for seven thousand years and more.

[Tout est dit, et l’on vient trop tard depuis plus de sept mille ans qu’il y a des hommes qui pensent.]Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 1 “Of Works of the Mind [Des Ouvrages de l’Esprit],” § 1 (1.1) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

Opening line of the book. La Bruyère's timeline is that of medieval scholars who calculated, from the Bible, that the age of the world to be only several thousand years old.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:We are come too late, after above seven thousand years that there have been men, and men have thought, to say any thing which has not been said already.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]After above seven thousand Years, that there have been Men, and Men have thought, we come too late to say any thing which has not been said already.

[Curll ed. (1713)]We are come too late, by several thousand Years, to say any thing new in Morality.

[Browne ed. (1752)]After above seven thousand years, during which there have been men who have thought, we come too late to say anything that has not been said already.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

Childhood is the world of miracle and wonder; as if creation rose, bathed in light out of the darkness, utterly new and fresh and astonishing. The end of childhood is when things cease to astonish us. When the world seems familiar, when one has got used to existence, one has become adult. The brave new world, the wonderland has grown trite and commonplace.

[L’enfance c’est le monde du miracle ou du merveilleux: c’est comme si la creation surgissait, lumineuse, de la nuit, toute neuve et toute fraîche, et tout étonnante. Il n’y a plus d’enfance à partir du moment où les choses ne sont plus étonnantes. Lorsque le monde vous semble «déja vu», lorsqu’on s’est habitué à l’existence, on devient adulte. Le monde de la féerie, la merveille neuve se fait banalité, cliché.]Eugène Ionesco (1912-1994) Romanian-French dramatist

Fragments of a Journal [Journal en Miettes], “The Crisis of Language” (1967) [tr. Stewart (1968)]

(Source)

Many pleasant things are better when they belong to someone else. You can enjoy them more that way. The first day, pleasure belongs to the owner; after that, to others. When things belong to others, we enjoy them twice as much, without the risk of losing them, and with the pleasure of novelty. Everything tastes better when we are deprived of it.

[Muchas cosas de gusto no se han de poseer en propiedad. Más se goza de ellas ajenas que propias. El primer día es lo bueno para su dueño, los demás para los extraños. Gózanse las cosas ajenas con doblada fruición, esto es, sin el riesgo del daño y con el gusto de la novedad. Sabe todo mejor a privación.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 264 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:Many things that serve for pleasure, ought not to be peculiar. One enjoys more of what is another's, than of what belongs to himself. The first day is for the Master, and all the rest for Strangers. One doubly enjoys what belongs to others, that's to say, not only without fear of loss, but also with the pleasure of Novelty. Privation makes every thing better.

[Flesher ed. (1685), §263]Many things of Taste one should not possess oneself. One enjoys them better if another's than if one's own. The owner has the good of them the first day, for all the rest of the time they are for others. You take a double enjoyment in other men's property, being without fear of spoiling it and with the pleasure of novelty. Everything tastes better for having been without it.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]Many of the things that bring delight should not be owned. They are more enjoyed if another's, than if yours; the first day they give pleasure to the owner, but in all the rest to the others: what belongs to another rejoices doubly, because without the risk of going stale, and with the satisfaction of freshness; everything tastes better after fasting.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

There is a strong conservative instinct in the average man or woman, born of the hereditary fear of life, that prompts them to cling to old standards, or, if too intelligent to look inhospitably upon progress, to move very slowly. Both types are the brakes and wheelhorses necessary to a stable civilization, but history, even current history in the newspapers, would be dull reading if there were no adventurous spirits willing to do battle for new ideas.

Gertrude Atherton (1857-1948) American author, essayist

The Living Present, Book 2, ch. 1, sec. 1 (1917)

(Source)

JUBA: Beauty soon grows familiar to the lover,

Fades in his eye, and palls upon the sense.

I like handling newborn animals. Fallen into life from an unmappable world, they are the ultimate immigrants, full of wonder and confusion.

Diane Ackerman (b. 1948) American poet, author, naturalist

The Moon by Whale Light, ch. 4 “White Lanterns” (1991)

(Source)

In art, there are only two types of people: revolutionaries and plagiarists. And in the end, doesn’t the revolutionary’s work become official, once the State takes it over?

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) French painter [Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin]

Letter in Le Soir (25 Apr 1895)

Collected in Daniel Guérin, ed., The Writings of a Savage (1996) [tr. Levieux].

Often given as "Art is either plagiarism or revolution," or sometimes "Art is either a revolutionist or a plagiarist." This is often cited from James Huneker, The Pathos of Distance (1913), but there it is given as a paraphrase: "Paul Gauguin has said that in art one is either a plagiarist or a revolutionary."

(Huneker's book elsewhere contains the parallel paraphrase, "Paul Gauguin has said that all artists are either revolutionists or reactionists.")

The saddest thing I can imagine is to get used to luxury.

Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) English comic actor, film director, composer

My Autobiography, ch. 22 (1964)

(Source)

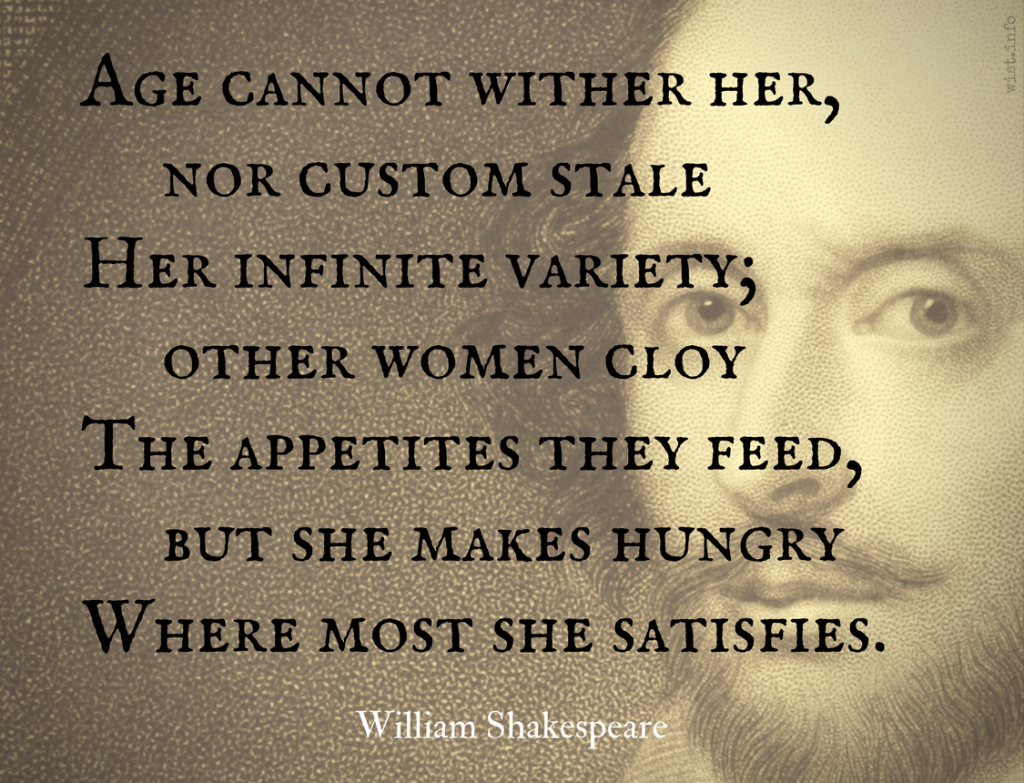

ENOBARBUS: Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety; other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Antony and Cleopatra, Act 2, sc. 2, l. 276ff (2.2.276-279) (1607)

(Source)

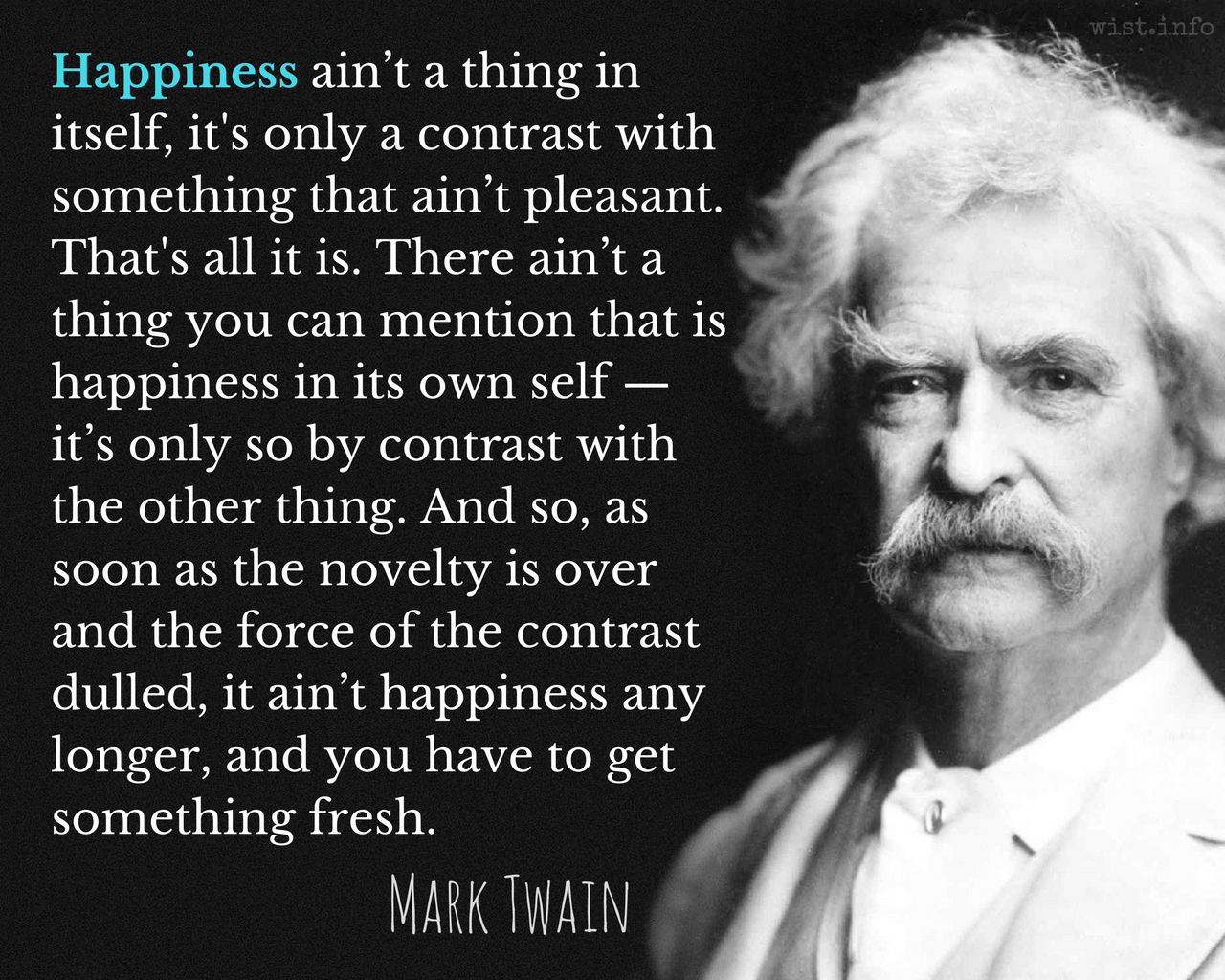

Happiness ain’t a thing in itself, it’s only a contrast with something that ain’t pleasant. That’s all it is. There ain’t a thing you can mention that is happiness in its own self — it’s only so by contrast with the other thing. And so, as soon as the novelty is over and the force of the contrast dulled, it ain’t happiness any longer, and you have to get something fresh.

The whole lesson of my life has been that no ‘methods of stimulation’ are of any lasting use. They are indeed like drugs — a stronger dose is needed each time and soon no possible dose is effective. We must not bother about thrills at all. Do the present duty — bear the present pain — enjoy the present pleasure — and leave emotions and ‘experiences’ to look after themselves.

Beauty loses its relish; the Graces, never: After the longest acquaintance, they are no less agreeable than at first.

Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696-1782) Scottish jurist, agriculturalist, philosopher, writer

Introduction to the Art of Thinking, ch. 4 (1761)

(Source)

Human life must be some kind of mistake. The truth of this will be sufficiently obvious if we only remember that man is a compound of needs and necessities hard to satisfy; and that even when they are satisfied, all he obtains is a state of painlessness, where nothing remains to him but abandonment to boredom. This is direct proof that existence has no real value in itself; for what is boredom but the feeling of the emptiness of life? If life — the craving for which is the very essence of our being — were possessed of any positive intrinsic value, there would be no such thing as boredom at all: mere existence would satisfy us in itself, and we should want for nothing. But as it is, we take no delight in existence except when we are struggling for something; and then distance and difficulties to be overcome make our goal look as though it would satisfy us — an illusion which vanishes when we reach it; or else when we are occupied with some purely intellectual interest — when in reality we have stepped forth from life to look upon it from the outside, much after the manner of spectators at a play. And even sensual pleasure itself means nothing but a struggle and aspiration, ceasing the moment its aim is attained. Whenever we are not occupied in one of these ways, but cast upon existence itself, its vain and worthless nature is brought home to us; and this is what we mean by boredom. The hankering after what is strange and uncommon — an innate and ineradicable tendency of human nature — shows how glad we are at any interruption of that natural course of affairs which is so very tedious.

[Daß das menschliche Daseyn eine Art Verirrung seyn müsse, geht zur Genüge aus der einfachen Bemerkung hervor, daß der Mensch ein Konkrement von Bedürfnissen ist, deren schwer zu erlangende Befriedigung ihm doch nichts gewährt, als einen schmerzlosen Zustand, in welchem er nur noch der Langenweile Preis gegeben ist, welche dann geradezu beweist, daß das Daseyn an sich selbst keinen Werth hat: denn sie ist eben nur die Empfindung der Leerheit desselben. Wenn nämlich das Leben, in dem Verlangen nach welchem unser Wesen und Daseyn besteht, einen positiven Werth und realen Gehalt in sich selbst hätte; so könnte es gar keine Langeweile geben: sondern das bloße Daseyn, an sich selbst, müßte uns erfüllen und befriedigen. Nun aber werden wir unsers Daseyns nicht anders froh, als entweder im Streben, wo die Ferne und die Hindernisse das Ziel als befriedigend uns vorspiegeln, welche Illusion nach der Erreichung verschwindet; oder aber in einer rein intellektuellen Beschäftigung, in welcher wir jedoch eigentlich aus dem Leben heraustreten, um es von außen zu betrachten, gleich Zuschauern in den Logen. Sogar der Sinnengenuß selbst besteht in einem fortwährenden Streben und hört auf, sobald sein Ziel erreicht ist. So oft wir nun nicht in einem jener beiden Fälle begriffen, sondern auf das Daseyn selbst zurückgewiesen sind, werden wir von der Gehaltlosigkeit und Nichtigkeit desselben überführt, und Das ist die Langeweile. Sogar das uns inwohnende und unvertilgbare, begierige Haschen nach dem Wunderbaren zeigt an, wie gern wir die so langweilige, natürliche Ordnung des Verlaufs der Dinge unterbrochen sähen.]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. 2, ch. 11 “The Vanity of Existence [Der Nichtigkeit des Daseins],” § 146 (1851)

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:That human life must be a kind of mistake is sufficiently clear from the fact that man is a compound of needs, which are difficult to satisfy; moreover, if they are satisfied, all he is granted is a state of painlessness, in which he can only give himself up to boredom. This is a precise proof that existence in itself has no value, since boredom is merely the feeling of the emptiness of life. If, for instance, life, the longing for which constitutes our very being, had in itself any positive and real value, boredom could not exist; mere existence in itself would supply us with everything, and therefore satisfy us. But our existence would not be a joyous thing unless we were striving after something; distance and obstacles to be overcome then represent our aim as something that would satisfy us -- an illusion which vanishes when our aim has been attained; or when we are engaged in something that is of a purely intellectual nature, when, in reality, we have retired from the world, so that we may observe it from the outside, like spectators at a theatre. Even sensual pleasure itself is nothing but a continual striving, which ceases directly its aim is attained. As soon as we are not engaged in one of these two ways, but thrown back on existence itself, we are convinced of the emptiness and worthlessness of it; and this it is we call boredom. That innate and ineradicable craving for what is out of the common proves how glad we are to have the natural and tedious course of things interrupted.

[tr. Dircks]That human existence must be some kind of error, is sufficiently clear from the simple observation that man is a concretion of needs and wants. Their satisfaction is hard to attain and yet affords him nothing but a painless state in which he is still abandoned to boredom. This, then, is a positive proof that, in itself, existence has no value; for boredom is just that feeling of its emptiness. Thus if life, in the craving for which our very essence and existence consist, had a positive value and in itself a real intrinsic worth, there could not possibly be any boredom. On the contrary, mere existence in itself would necessarily fill our hearts and satisfy us. Now we take no delight in our existence except in striving for something when the distance and obstacles make us think that the goal will be satisfactory, an illusion that vanishes when it is reached; or else in a purely intellectual occupation where we really step out of life in order to contemplate it from without, like spectators in the boxes. Even sensual pleasure itself consists in a constant striving and ceases as soon as its goal is attained. Now whenever we are not striving for something or are not intellectually occupied, but are thrown back on existence itself, its worthlessness and vanity are brought home to us; and this is what is meant by boredom. Even our inherent and ineradicable tendency to run after what is strange and extraordinary shows how glad we are to see an interruption in the natural course of things which is so tedious.

[tr. Payne (1974)]

Such is the state of life, that none are happy but by the anticipation of change: the change itself is nothing; when we have made it, the next wish is to change again. The world is not yet exhausted; let me see something tomorrow which I never saw before.

In fact, nothing is ever said that has not been said before.

[Nullum est iam dictum quod non dictum sit prius.]

Terence (186?-159 BC) African-Roman dramatist [Publius Terentius Afer]

The Eunuch [Eunuchus], l. 41, Prologue (161 BC) [tr. Bolton (2019)]

(Source)

Alternate translations:

- "In short, there's Nothing say'd , but what before / May have been say'd." [tr. Cooke (1755)]

- "In fine, nothing can be said now, that may not have been said before." [tr. Patrick (1767)]

- "Nothing's said now, but has been said before." [tr. Coleman (1768)]

- "In fine, nothing is said now that has not been said before." [tr. Riley (1853)]

- "Ah, there is nothing new beneath the sun, / Whatever is, or may be, has been done." [tr. Rose (1870)]

- "In fact nothing is said that has not been said before." [tr. Sargeaunt (1918)]

- "The bottom line: you can't say anything that's never been said before." [tr. Christenson (2012)]

- There's nothing ever said, unsaid before. [tr. Bolton (2019), shortened Prologue]

Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.

He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils; for time is the greatest innovator.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

“Of Innovations,” Essays, No. 24 (1625)

(Source)