Quotations about:

popular opinion

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

It is generally pride rather than lack of intelligence which prompts men to dispute so obstinately generally accepted opinions; they find all the front seats taken on the popular side, and do not wish to sit behind.

[C’est plus souvent par orgueil que par défaut de lumières qu’on s’oppose avec tant d’opiniâtreté aux opinions les plus suivies: on trouve les premières places prises dans le bon parti, et on ne veut point des dernières.]

François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) French epigrammatist, memoirist, noble

Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales [Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims], ¶234 (1665-1678) [tr. Stevens (1939)]

(Source)

This passage first appeared in the 5th (1678) edition. Earlier English translations do not include it.

See also Gracián (1647).

In the manuscript version, "C'est ... d’opiniâtreté" is given as: "C’est par orgueil qu’on s’oppose avec tant d’opiniâtreté … [It is out of pride that they oppose with such stubbornness ...]," removing the comment about lack of understanding / intelligence.

(Source (French)). Other translations:It is more often from pride than from want of intelligence that people oppose with so much obstinacy; the most received opinions. They find the best places taken up in the good party, and do not like to put up with inferior ones.

[ed. Gowens (1851), ¶380]It is more often from pride than from ignorance that we are so obstinately opposed to current opinions; we find the first places taken, and we do not want to be the last.

[tr. Bund/Friswell (1871), ¶234]It is more often our pride than our limited understanding which makes us fly so violently in the face of public opinion. We find the best seats on the correct side already occupied, and we do not care to sit in the rear.

[tr. Heard (1917), ¶377]Pride, rather than a lack of perspicacity, is what usually drives us to oppose with such obstinacy opinions that are generally accepted as correct: though theirs may be the better party, the front benches are already filled, and we certainly do not want to take a back seat.

[tr. FitzGibbon (1957), ¶234]It is oftener through pride than through lack of understanding that we so militantly object to prevailing opinions; we find the front seats already in other hands, and we do not want rear ones.

[tr. Kronenberger (1959), ¶234]Those who obstinately oppose the most widely-held opinions more often do so because of pride than lack of intelligence. They find the best places in the right set already taken, and they do not want back seats.

[tr. Tancock (1959), ¶234]It is more often from pride than from ignorance that we so stubbornly oppose ourselves to the most current opinions: we find the first seats already taken on the better side, and do not wish to sit down there last.

[tr. Whichello (2016) ¶234]

Where the environment is stupid or prejudiced or cruel, it is a sign of merit to be out of harmony with it.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

Conquest of Happiness, Part 1, ch. 9 “Fear of Public Opinion” (1930)

(Source)

The voice of the people is the voice of God.

[Vox populi, vox Dei.]

Alcuin of York (c. 735-804) Anglo-Latin scholar, clergyman, poet, teacher [Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus, Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin]

Letter (AD 798) to Charlemagne

Collected as Epistle 166, "Capitula quę tali convenit in tempore memorari," sec. 9 in various collections. (The epistle number varies.)

Alcuin did not actually invent the phrase -- though his use of it is one of the earliest recorded references. Ironically, while the phrase means that the popular will / voice / opinion is divine will, Alcuin used it while denying it:Nec audiendi qui solent dicere: Vox populi, vox Dei. Cum tumultuositas vulgi semper insaniæ proxima sit.

[And those people should not be listened to who keep saying the voice of the people is the voice of God, since the riotousness of the crowd is always very close to madness.

[Source]

[We should not listen to those who like to affirm that the voice of the people is the voice of God, for the tumult of the masses is truly close to madness.]

[Source]

There is also some question as to whether this is an authentic Alcuin quote. For more information about the phrase, see here.

Well then, is there anyone — besides those who were glad that he had turned into a king — who did not want this deed to happen, or failed to approve of it afterwards? So all are guilty. All loyal citizens, so far as was in their power, killed Caesar. Not everyone had a plan, not everyone had the courage, not everyone had the opportunity — but everyone had the will.

[Ecquis est igitur exceptis eis qui illum regnare gaudebant qui illud aut fieri noluerit aut factum improbarit? Omnes ergo in culpa. Etenim omnes boni, quantum in ipsis fuit, Caesarem occiderunt: aliis consilium, aliis animus, aliis occasio defuit; voluntas nemini.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Philippics [Philippicae; Antonian Orations], No. 2, ch. 12 / sec. 29 (2.12/2.29) (44-10-24 BC) [tr. Berry (2006)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Other translations:Is there anyone, then, except those who rejoiced in his kingly sway, who either was unwilling that the deed should be done or has impugned it since? All therefore share in the fault, for all loyal citizens, so far as rested with them, took part in Cæsar's death. Some wanted the necessary powers of contrivance, some the courage, some the opportunity; but not one the will.

[tr. King (1877)]Is there then any man, except those that were glad of his reign, who repudiated that deed, or disapproved of it when it was done? All therefore are to blame, for all good men, so far as their own power went, slew Caesar; some lacked a plan, others courage, others opportunity: will no man lacked.

[tr. Ker (Loeb) (1926)]Is there any one then, except you yourself and these men who wished him to become a king, who was unwilling that that deed should be done, or who disapproved of it after it was done? All men, therefore, are guilty as far as this goes. In truth, all good men, as far as it depended on them, bore a part in the slaying of Caesar. Some did not know how to contrive it, some had not courage for it, some had no opportunity, -- every one had the inclination.

[tr. Yonge (1903)]Yet, with the exception of the men who wanted to make an autocratic monarch of him, all were happy for this to happen -- or were glad when it had happened. So everyone is guilty! For every decent person, in so far as he had any say in the matter, killed Caesar! Plans, courage, opportunities were in some case lacking; but the desire nobody lacked.

[tr. Grant (1960)]Is there anyone, with the exception of those who were happy that he was our king, who did not want it done or disapproved that it was done? Everyone is at fault, then. Indeed, all decent men, as far as they could, killed Caesar; some may have lacked a plan, others courage, and still others the opportunity, but no one lacked the desire.

[tr. McElduff (2011)]

Endeavour rather to get the Approbation of a few good Men, than the Huzza of the Mob.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 1, # 512 (1725)

(Source)

The man of firm and righteous will,

No rabble, clamorous for the wrong,

No tyrant’s brow, whose frown may kill,

Can shake the strength that makes him strong.[Iustum et tenacem propositi virum

non civium ardor prava iubentium,

non voltus instantis tyranni

mente quatit solida]Horace (65–8 BC) Roman poet, satirist, soldier, politician [Quintus Horatius Flaccus]

Odes [Carmina], Book 3, # 3, l. 1ff (3.3.1-4) (23 BC) [tr. Conington (1872)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:An honest and resolved man,

Neither a peoples tumults can,

Neither a Tyrants indignation,

Un-center from his fast foundation.

[tr. Fanshaw; ed. Brome (1666)]Not the rage of the people pressing to hurtful measures, not the aspect of a threatening tyrant can shake from his settled purpose the man who is just and determined in his resolution.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]He that is just, and firm of will

Doth not before the fury quake

Of mobs that instigate to ill,

Nor hath the tyrant's menace skill

His fixed resolve to shake.

[tr. Martin (1864)]Not the rage of the million commanding things evil,

Not the doom frowning near in the brows of the tyrant,

Shakes the upright and resolute man

In his solid completeness of soul.

[tr. Bulwer-Lytton (1870)]Neither the fury of the populace, commanding him to do what is wrong, nor the face of the despot which confronts him, [...] shakes from his solid resolve a just and determined man.

[tr. Elgood (1893)]The just man, in his purpose strong,

No madding crowd can bend to wrong.

The forceful tyrant's brow and word,

[...] His firm-set spirit cannot move.

[tr. Gladstone (1894)]Him who is just, and stands to his purpose true.

Not the unruly ardour of citizens

Shall shake from his firm resolution,

Nor visage of the oppressing tyrant.

[tr. Phelps (1897)]The upright man holding his purpose fast,

No heat of citizens enjoining wrongful acts,

No overbearing despot's countenance,

Shakes from his firm-set mind.

[tr. Garnsey (1907)]The man that's just and resolute of mood

No craze of people's perverse vote can shake,

Nor frown of threat'ning monarch make

To quit a purposed good.

[tr. Marshall (1908)]The man tenacious of his purpose in a righteous cause is not shaken from his firm resolve by the frenzy of his fellow citizens bidding what is wrong, not by the face of threatening tyrant.

[tr. Bennett (Loeb) (1912)]Who loves the Right, whose will is resolute,

His purpose naught can shake — nor rage of brute

Mob bidding him work evil; nor the eye

Of threatening despot

[tr. Mills (1924)]A mob of citizens clamouring for injustice,

An autocrat's grimace of rage [...] cannot stagger

The just and steady-purposed man.

[tr. Michie (1963)]The man who knows what's right and is tenacious

In the knowledge of what he knows cannot be shaken.

Not by people righteously impassioned

In a wrong cause, and not by menacings

Of tyrants' frowns.

[tr. Ferry (1997)]The just man, tenacious in his resolve,

will not be shaken from his settled purpose

by the frenzy of his fellow citizens

imposing that evil be done,

or by the frown of a threatening tyrant.

[tr. Alexander (1999)]The passion of the public, demanding what

is wrong, never shakes the man of just and firm

intention, from his settled purpose,

nor the tyrant’s threatening face.

[tr. Kline (2015)]Neither the passion of citizens demanding crooked things,

Not the face of a threatening tyrant

Shakes the man who is righteous and set in purpose

From his strong mind.

[tr. Wikisource (2021)]

There is nothing which a prudent man must shun more carefully than living with a view to popularity and giving serious thought to the things esteemed by the multitude, instead of making sound reason his guide of life, so that, even if he must gainsay all men and fall into disrepute and incur danger for the sake of what is honourable, he will in no wise choose to swerve from what has been recognized as right.

[ἀλλ᾽ οὐκ ἔστιν ὃ μᾶλλον φευκτέον τῷ σωφρονοῦντι, τοῦ πρὸς δόξαν ζῆν, καὶ τὰ τοῖς πολλοῖς δοκοῦντα περισκοπεῖν, καὶ μὴ. τὸν ὀρθὸν λόγον ἡγεμόνα ποιεῖσθαι τοῦ βίου, ὥστε, κἂν πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις ἀντιλέγειν, κἂν ἀδοξεῖν καὶ κινδυνεύειν ὑ ὑπὲρ τοῦ καλοῦ δέῃ, μηδὲν αἱρεῖσθαι τῶν ὀρθῶς ἐγνωσμένων παρακινεῖν.]

Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-378) Christian bishop, theologian, monasticist, Doctor of the Church [Saint Basil the Great, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας]

Address to Young Men on Reading Greek Literature, ch. 9, sec. 25 [tr. Deferrari/McGuire (1933)]

(Source)

To found the reward for virtuous actions on the approval of others is to choose too uncertain and shaky a foundation. Especially in an age as corrupt and ignorant as this, the good opinion of the people is a dishonor. Whom can you trust to see what is praiseworthy?

[De fonder la recompence des actions vertueuses, sur l’approbation d’autruy, c’est prendre un trop incertain et trouble fondement, signamment en un siecle corrompu et ignorant, comme cettuy cy la bonne estime du peuple est injurieuse. A qui vous fiez vous, de veoir ce qui est louable?]Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 3, ch. 2 (3.2), “Of Repentance [Du Repentir]” (1586) [tr. Frame (1943)]

(Source)

This essay first appeared in the 1588 ed. The second sentence/phrase (on the age being so corrupt) and following were added for the 1595 ed.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:To ground the recompence of vertuous actions, upon the approbation of others, is to undertake a most uncertaine or troubled foundation, namely in an age so corrupt and times so ignorant, as this is: the vulgar peoples good opinion is injurious. Whom trust you in seeing what is commendable?

[tr. Florio (1603)]To ground the Recompence of virtuous Actions upon the Approbation of others, is too uncertain and unsafe a Foundation; especially in so corrupt and ignorant an Age as this, the good Opinion of the Vulgar is injurious. Upon whom do you relie to shew you what is recommendable?

[tr. Cotton (1686)]To ground the recompense of virtuous actions upon the approbation of others is too uncertain and unsafe a foundation, especially in so corrupt and ignorant an age as this, wherein the good opinion of the vulgar is injurious: upon whom do you rely to show you what is recommendable?

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]To base the reward of virtuous actions on the approbation of others is to choose a too uncertain and obscure foundation. Especially in a corrupt and ignorant age like this, the good opinion of the vulgar is offensive; to whom do you trust to perceive what is praiseworthy?

[tr. Ives (1925)]Basing the recompense of virtuous deeds on another’s approbation is to accept too uncertain and confused a foundation -- especially since in a corrupt and ignorant period like our own to be in good esteem with the masses is an insult: whom would you trust to recognize what was worthy of praise!

[tr. Screech (1987)]

No solitary miscreant, scarcely any solitary maniac, would venture on such actions and imaginations, as large communities of sane men have, in such circumstances, entertained as sound wisdom.

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

Essay (1829-06), “Signs of the Times,” Edinburgh Review No. 98, Art. 7

(Source)

I speak what appears to me the general opinion; and where an opinion is general, it is usually correct.

For a truth, once established by proof, does neither gain force nor certainty by the consent of all scholars, nor lose by the general dissent.

Maimonides (1135-1204) Spanish Jewish philosopher, scholar, astronomer, physician [Moses ben Maimon, Rambam, רמב״ם]

Guide for the Perplexed, Part 2, ch. 15 (c. 1190) [tr. Friedlander (1885)]

(Source)

Alternate translation:For when something has been demonstrated, the correctness of the matter is not increased and certainty regarding it is not strengthened by the consensus of all men of knowledge with regard to it. Nor could its correctness be diminished and certainty regarding it be weakened even if all the people on earth disagreed with it.

[tr. Pines (1963)]

Free yourself from common foolishness. This requires a special sort of sanity. Common foolishness is authorized by custom, and some people who resisted the ignorance of individuals were unable to resist that of the multitude.

[Librarse de las necedades comunes. Es cordura bien especial. Están muy validas por lo introducido, y algunos, que no se rindieron a la ignorancia particular, no supieron escaparse de la común.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 209 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:Not to imitate the folly of others is an effect of rare wisedome; for whatever is introduced by example and custome, is of great force. Some who have guarded against particular ignorance, have not been able to avoid the general.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Keep yourself free from common Follies. This is a special stroke of policy. They are of special power because they are general, so that many who would not be led away by any individual folly cannot escape the universal failing.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]To keep free from the popular inanities, marks especially good sense. They are highly esteemed because so well introduced, and many a man who could not be trapped by some particular stupidity could not except the general.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

A Man is glad to gain Numbers on his Side, as they serve to strengthen him in his private Opinions. Every Proselyte is like a new Argument for the Establishment of his Faith. It makes him believe that his Principles carry Conviction with them, and are the more likely to be true, when he finds they are conformable to the Reason of others, as well as to his own. And that this Temper of Mind deludes a Man very often into an Opinion of his Zeal, may appear from the common Behaviour of the Atheist, who maintains and spreads his Opinions with as much Heat as those who believe they do it only out of Passion for God’s Glory.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Essay (1711-10-02), The Spectator, No. 185

(Source)

The rule which should guide us in such cases is simple and obvious enough: that the aggregate testimony of our neighbours is subject to the same conditions as the testimony of any one of them. Namely, we have no right to believe a thing true because everybody says so unless there are good grounds for believing that some one person at least has the means of knowing what is true, and is speaking the truth so far as he knows it. However many nations and generations of men are brought into the witness-box, they cannot testify to anything which they do not know. Every man who has accepted the statement from somebody else, without himself testing and verifying it, is out of court; his word is worth nothing at all. And when we get back at last to the true birth and beginning of the statement, two serious questions must be disposed of in regard to him who first made it: was he mistaken in thinking that he knew about this matter, or was he lying?

William Kingdon Clifford (1845-1879) English mathematician and philosopher

“The Ethics of Belief,” Part 2 “The Weight of Authority,” Contemporary Review (Jan 1877)

(Source)

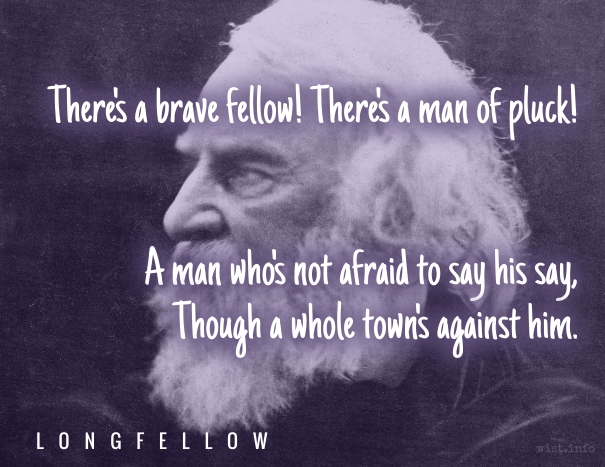

There’s a brave fellow! There’s a man of pluck!

A man who’s not afraid to say his say,

Though a whole town’s against him.

Civil liberties had their origin and must find their ultimate guaranty in the faith of the people. If that faith should be lost, five or nine men in Washington could not long supply its want.

Robert H. Jackson (1892-1954) US Supreme Court Justice (1941-54), lawyer, jurist, politician

Douglas v. Jeannette 319 U.S. 157, 181 (1943) [concurring]

(Source)

First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility.

Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied.

Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds.

And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) English philosopher and economist

On Liberty, ch. 2 “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion” (1859)

(Source)

HECUBA: Then no man on earth is truly free,

All are slaves of money or necessity.

Public opinion or fear of prosecution

forces each one, against his conscience,

to conform.ἙΚΆΒΗ:[φεῦ.

οὐκ ἔστι θνητῶν ὅστις ἔστ’ ἐλεύθερος·

ἢ χρημάτων γὰρ δοῦλός ἐστιν ἢ τύχης

ἢ πλῆθος αὐτὸν πόλεος ἢ νόμων γραφαὶ

εἴργουσι χρῆσθαι μὴ κατὰ γνώμην τρόποις.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Hecuba [Hekabe; Ἑκάβη], l. 864ff (c. 424 BC) [tr. Arrowsmith (1958)]

(Source)

When Agamemnon claims he cannot help her get revenge, as much as he'd like to if he were free to assist, because he has to pay attention to the sentiments of the Greek army.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Alas! there's no man free: for some are slaves

To gold, to fortune others, and the rest,

The multitude or written laws restrain

From acting as their better judgement dictates.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]Alas! no mortal is there who is free. For either he is the slave of money or of fortune; or the populace of the city or the dictates of the law constrain him to adopt manners not accordant with his natural inclinations.

[tr. Edwards (1826)]Vain is the boast of liberty in man;

A slave to fortune, or a slave to wealth,

Or by the people or the laws restrain’d,

He dares not act the dictates of his will

[ed. Ramage (1864)]Ah, among mortals is there no man free!

To lucre or to fortune is he slave:

The city's rabble or the laws' impeachment

Constrains him into paths his soul abhors.

[tr. Way (Loeb) (1894)]Ah! there is not in the world a single man free; for he is a slave either to money or to fortune, or else the people in their thousands or the fear of public prosecution prevents him from following the dictates of his heart.

[tr. Coleridge (1938)]Show me the mortal man who's really free.

He's either a slave to money or to chance.

Or the pressure of the mob or legal code

curbs him from acting as his will dictates.

[tr. Harrison (2005)]Ah! But there’s no such thing as a free man! All men are slaves, Agamemnon! Slaves to money, to Fate, to the cries of the masses, to the written laws! They all stop him from doing what he wants.

[tr. Theodoridis (2007)]Then no one is free

in this world. He’s chained to money, or to luck, or to majority

opinion, or to law. Any way you look at it,

he’s still a slave.

[tr. Karden/Street (2011)]Alas!

there is not in the world a single man who is free;

for he is a slave either to money or to fortune,

or else the mob, or fear of law, prevents him

from following the dictates of his heart.

[ed. Yeroulanos (2016)]There is no mortal who is free. Either he is a slave to money or fortune, or the city’s mob or its laws make him live otherwise than he would wish.

[tr. @sentantiq (2016)]Ha!

No one who is mortal is free --

We are either the slave of money or chance;

Or the majority of people or the city’s laws

Keep us from living by our own judgment.

[tr. @sentantiq (2020)]

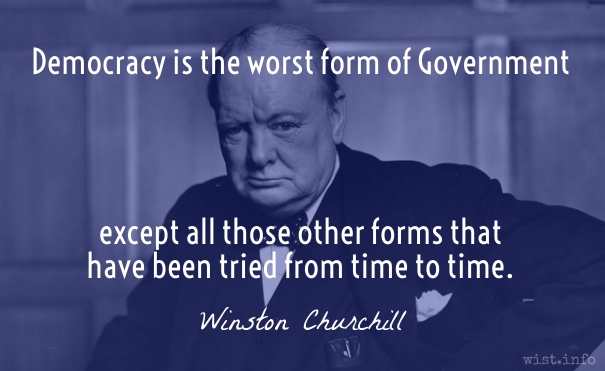

Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.

When, however, the lay public rallies round an idea that is denounced by distinguished but elderly scientists and supports that idea with great fervor and emotion — the distinguished but elderly scientists are then, after all, probably right.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

Fantasy & Science Fiction (in answer to Clarke’s First Law) (1977)

See Clarke.

A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech (1861-03-04), Inaugural Address, Washington, D. C.

(Source)

Man prefers to believe what he wants to be true. He rejects what is difficult because he is too impatient to make the investigation; he rejects sensible ideas, because they limit his hopes; he rejects the deeper truths of nature because of superstition; he rejects the light of experience, because he is arrogant and fastidious, believing that the mind should not be seen to be spending its time on mean, unstable things; and he rejects anything unorthodox because of common opinion. In short, emotion marks and stains the understanding in countless ways which are sometimes impossible to perceive.

[Quod enim mavult homo verum esse, id potius credit. Rejicit itaque difficilia, ob inquirendi impatientiam; sobria, quia coarctant spem; altiora naturae, propter superstitionem; lumen experientiae, propter arrogantiam et fastum, ne videatur mens versari in vilibus et fluxis; paradoxa, propter opinionem vulgi; denique innumeris modis, iisque interdum imperceptibilibus, affectus intellectum imbuit et inficit.]

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

Instauratio Magna [The Great Instauration], Part 2 “Novum Organum [The New Organon],” Book 1, Aphorism # 49 (1620) [tr. Silverthorne (2000)]

(Source)

See Demosthenes.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For man always believes more readily that which he prefers. He, therefore, rejects difficulties for want of patience in investigation; sobriety, because it limits his hope; the depths of nature, from superstition; the light of experiment, from arrogance and pride, lest his mind should appear to be occupied with common and varying objects; paradoxes, from a fear of the opinion of the vulgar; in short, his feelings imbue and corrupt his understanding in innumerable and sometimes imperceptible ways.

[tr. Wood (1831)]For what a man had rather were true he more readily believes. Therefore he rejects difficult things from impatience of research; sober things, because they narrow hope; the deeper things of nature, from superstition; the light of experience, from arrogance and pride, lest his mind should seem to be occupied with things mean and transitory; things not commonly believed, out of deference to the opinion of the vulgar. Numberless in short are the ways, and sometimes imperceptible, in which the affections colour and infect the understanding.

[tr. Spedding (1858)]For man more readily believes what he wishes to be true. And so it rejects difficult things, from impatience of inquiry; -- sober things, because they narrow hope; -- the deeper thigns of Nature, from superstition; -- the light of experience, from arrogance and disdain, lest the mind should seem to be occupied with worthless and changing matters; -- paradoxes, from a fear of the opinion of the vulgar: -- in short, the affections enter and corrupt the intellect in innumerable ways, and these sometimes imperceptible.

[tr. Johnson (1859)]For a man is more likely to believe something if he would like it to be true. Therefore he rejectsIn short, there are countless ways in which, sometimes imperceptibly, a person’s likings colour and infect his intellect.

- difficult things because he hasn’t the patience to research them,

- sober and prudent things because they narrow hope,

- the deeper things of nature, from superstition,

- the light that experiments can cast, from arrogance and pride (not wanting people to think his mind was occupied with trivial things),

- surprising truths, out of deference to the opinion of the vulgar.

[tr. Bennett (2017)]

Virtue has never been as respectable as money.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

The Innocents Abroad, ch. 23 (1869)

(Source)