Although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.

Quotations by:

Lincoln, Abraham

We here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not vanish from this earth.

In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be, wrong. God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.

Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser — in fees, and expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker the lawyer has a superior opertunity [sic] of being a good man. There will still be business enough.

The probability that we may fall in the struggle ought not deter us from the support of a cause we believe to be just; it shall not deter me.

Holding it a sound maxim that it is better to be only sometimes right than at all times wrong, so soon as I discover my opinions to be erroneous I shall be ready to renounce them.

Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.

You have heard the story, haven’t you, about the man who was tarred and feathered and carried out of town on a rail? A man in the crowd asked him how he liked it. His reply was that if it was not for the honor of the thing, he would much rather walk.

I do the very best I know how — the very best I can; and I mean to keep doing so until the end. If the end brings me out all right, what is said against me won’t amount to anything. If the end brings me out wrong, ten angels swearing I was right would make no difference.

It has been my experience that folks who have no vices have very few virtues.

People who like this sort of thing will find this the sort of thing they like.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

One of the earliest references to something like this was in an 1863 newspaper ad for Lincoln’s favorite humorist, Artemus Ward, that included this faux testimonial (possibly written by Ward): “I have never heard any of your lectures, but from what I can learn I should say that for people who like the kind of lectures you deliver, they are just the kind of lectures such people like. Yours respectfully, O. Abe.”

Quoted in G.W.E. Russell, Collections and Recollections, ch. 30 (1898), regarding “an unreadably sentimental book.”

According to Anthony Gross, Lincoln’s Own Stories (1902), Lincoln’s was speaking to Robert Dale Owen, who had insisted on reading to Lincoln a long manuscript on spiritualism. "Well, for those who like that sort of thing, I should think it is just about the sort of thing they would like."

In Emanual Hertz, ed., "Father Abraham," Lincoln Talks: A Biography in Anecdote (1939), the response was to a young poet asking him about his newly published poems.

More discussion of this quotation: Ralph Keyes, The Quote Verifier.

He can compress the most words into the smallest ideas of any man I ever met.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

Quoted in Frederick Trevor Hill, Lincoln the Lawyer, ch. 19 (1906). Hill adds, "History has considerately sheltered the identity of the victim."

I care not for a man’s religion whose dog or cat are not the better for it.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

Frequently attributed to Lincoln without citation, it's actually a variant of "I would give nothing for that man's religion, whose very dog and cat are not the better for it," by Rowland Hill (1744-1833), an English preacher, attributed in George Seaton Bowes, Illustrative Gatherings, or, Preachers and Teachers (1860). Lincoln may have used the line.

All through life be sure you put your feet in the right place, then stand firm.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

Quoted in William M Thayer, The Pioneer Boy (1882).

I destroy my enemies when I make them my friends.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

No early authority has been found citing this from Lincoln. However, in The Sociable Story-teller (1846), Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor 1410-1437, was quoted : "Do I not most effectually destroy my enemies, in making them my friends?"

You may fool all the people some of the time; you can even fool some of the people all the time; but you can’t fool all of the people all the time.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

A possible precursor to this quote is the widely-republished Jacques Abbadie, "Traité de la Vérité de la Religion Chrétienne," ch. 2 (1684): "One can fool some men, or fool all men in some places and times, but one cannot fool all men in all places and ages. [… ont pû tromper quelques hommes, ou les tromper tous dans certains lieux & en certains tems, mais non pas tous les hommes, dans tous les lieux & dans tous les siécles.]" A similar passage was used in Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, ed., Encyclopédie: ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, Vol. 4 (1754).

First attributed to Lincoln by Fred F. Wheeler, interviewed in the Albany Times (8 Mar 1886): "You can fool part of the people some of the time, you can fool some of the people all of the time, but you cannot fool all the people all of the time."

First cited in detail in Alexander K. McClure, “Abe” Lincoln’s Yarns and Stories, (1904), in the above form; it was cited as a speech in Clinton, Ill. (2 Sep 1858), but the passage is not found in any surviving Lincoln documents. No Lincoln reference is found in contemporary writings.

Also attributed to P.T. Barnum and Bob Dylan. See also Lawrence J. Peter. More detailed discussion of the quotation can be found here.

Honest statesmanship is the wise employment of individual meannesses for the public good.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

(Source)

Attributed in John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, vol. 10, ch. 18 "Lincoln's Fame" (1886).

You must remember that some things that are legally right are not morally right.

Perhaps a man’s character is like a tree, and his reputation like its shadow; the shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.

Books serve to show a man that those original thoughts of his aren’t very new after all.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Attributed)

(Source)

Recounted in the Pennsylvania School Journal, Vol. 46, #7 (Jan 1898) as an anecdote from a clergyman printed in the New York Tribune.

I am not at all concerned about that, for I know that the Lord is always on the side of the right; but, it is my constant anxiety and prayer that I, and this nation, should be on the Lord’s side.

Oh, if there is a man out of hell that suffers more than I do, I pity him.

Most of us are just about as happy as we make up our minds to be.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Spurious)

Not found any earlier than in casual attribution in 1914. More info here.

I am a firm believer in the people. If given the truth, they can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

(Spurious)

Frequently quoted, but does not appear in the record of Lincoln's writings or in any first person account.

There is no honorable way to kill, no gentle way to destroy. There is nothing good in war — except its ending.

It is said an Eastern monarch once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence, to be ever in view, and which should be true and appropriate in all times and situations. They presented him the words: “And this, too, shall pass away.” How much it expresses! How chastening in the hour of pride! — how consoling in the depth of affliction!

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

By the frame of the Government under which we live this same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief, and have with equal wisdom provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals. While the people retain their virtue and vigilance no Administration by any extreme of wickedness or folly can very seriously injure the Government in the short space of four years.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

First Inaugural Address (4 Mar 1861)

Full text

I am loathe to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

The legitimate object of government, is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but can not do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves — in their separate, and individual capacities. In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, government ought not to interfere.

The desirable things which the individuals of a people can not do, or can not well do, for themselves, fall into two classes: those which have relation to wrongs, and those which have not. Each of these branch off into an infinite variety of subdivisions. The first — that in relation to wrongs — embraces all crimes, misdemeanors, and non-performance of contracts. The other embraces all which, in its nature, and without wrong, requires combined action, as public roads and highways, public schools, charities, pauperism, orphanage, estates of the deceased, and the machinery of government itself.

From this it appears that if all men were just, there still would be some, though not so much, need of government.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Fragment (1 Jul 1854?)

(Source)

In Roy P. Basler (ed.), Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Vol. 2 (1953). The date, by Nicolay and Hay, is deemed arbitrary.

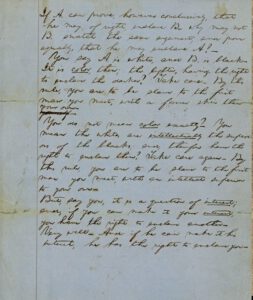

If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B. — why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly? — You mean the whites are intellectually the superior of blacks, and, therefore, have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Fragment on Slavery (c. 1854)

(Source)

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Inaugural Address, conclusion (4 Mar 1865)

(Source)

Slavery is doomed, and that within a few years. Even Judge Douglas admits it to be an evil, and an evil can’t stand discussion. In discussing it we have taught a great many thousands of people to hate it who had never given it a thought before. What kills the skunk is the publicity it gives itself.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Interview with David R. Locke (1859)

(Source)

Recounted in A. T. Rice, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, ch. 25 (1896).

I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.

This is a world of compensation; and he who would be no slave must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves, and, under a just God, cannot long retain it.

Quarrel not at all. No man resolved to make the most of himself can spare time for personal contention. Still less can he afford to take all the consequences, including the vitiating of his temper and loss of self control. Yield larger things to which you can show no more than equal right; and yield lesser ones, though clearly your own. Better give your path to a dog than be bitten by him in contesting for the right. Even killing the dog would not cure the bite.

Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time. It will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost.

Let us diligently apply the means, never doubting that a just God, in his own good time, will give us the rightful result.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Letter to James C. Conkling (26 Aug 1863)

(Source)

Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except Negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except Negroes and foreigners and Catholics.” When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Letter to Joshua Speed (1855-08-24)

(Source)

I must save this government if possible. What I cannot do, of course I will not do; but it may as well be understood, once for all, that I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.

Allow the President to invade a neighboring nation whenever he shall deem it necessary to repel an invasion, and you shall allow him to do so whenever he may choose to say he deems it necessary for such purpose, and you allow him to make war at pleasure. Study to see if you can fix any limit to his power in this respect. If today he should choose to say he thinks it necessary to invade Canada to prevent the British from invading us, how could you stop him? You may say to him, “I see no probability of the British invading us”; but he will say to you, “Be silent: I see it if you don’t.”

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Letter to William Herndon (15 Feb 1848)

Full text.

I think the authors of that notable instrument intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all men were equal in color, size, intellect, moral development, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness in what they did consider all men created equal — equal in “certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This they said, and this they meant. They did not mean to assert the obvious untruth that all were then actually enjoying that equality, or yet that they were about to confer it immediately upon them. In fact, they had no power to confer such a boon. They meant simply to declare the right, so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit. They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society which should be familiar to all, constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere.

In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who molds public sentiment goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statues and decisions possible or impossible to be executed.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Lincoln-Douglas Debates, Debate #1, Ottawa, Illinois (21 Aug 1858)

(Source)

It was a time when a man with a policy would have been fatal to the country. I have never had a policy; I have simply tried to do what seemed best each day as each day came.

Die when I may, I want it said of me by those who knew me best that I always plucked a thistle and planted a flower where I thought a flower would grow.

How hard, oh, how hard it is to die and leave one’s country no better than if one had never lived for it.

Often an idea would occur to me which seemed to have force. … I never let one of those ideas escape me, but wrote it on a scrap of paper and put it in that drawer. In that way I saved my best thoughts on the subject, and, you know, such things often come in a kind of intuitive way more clearly than if one were to sit down and deliberately reason them out. To save the results of such mental action is true intellectual economy.

The true rule, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. Almost every thing, especially of governmental policy, is an inseparable compound of the two; so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Remarks, House of Representatives (1848-06-20)

(Source)

Speaking on internal improvements (infrastructure) as part of governmental policy.

I am approached with the most opposite opinions and advice, and that by religious men, who are equally certain that they represent the Divine will. I am sure that either the one or the other class is mistaken in the belief, and perhaps in some respects both. I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say that if it is probable that God would reveal his will to others, on a point so connected with my duty, it might be supposed he would reveal it directly to me; for, unless I am more deceived in myself than I often am, it is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is I will do it! These are not, however, the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation. I must study the plain physical facts of the case, ascertain what is possible and learn what appears to be wise and right. The subject is difficult, and good men do not agree.

That some should be rich, shows that others may become rich, and hence is just encouragement to industry and enterprize. Let not him who is houseless pull down the house of another; but let him labor diligently and build one for himself, thus by example assuring that his own shall be safe from violence when built.

I desire to conduct the affairs of this administration that if at the end, when I come to lay down the reins of power, I have lost every other friend on earth, I shall at least have one friend left, and that friend shall be down inside of me.

The true rule, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. Almost every thing, especially of governmental policy, is an inseparable compound of the two; so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech (1848-06-20), On Internal Improvements, US House of Representatives

(Source)

What I do say is that no man is good enough to govern another man without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle, the sheet-anchor of American republicanism. […] According to our ancient faith, the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed. Now the relation of master and slave is pro tanto a total violation of this principle. The master not only governs the slave without his consent, but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes for himself. Allow all the governed an equal voice in the government, and that, and that only, is self-government.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech at Peoria, Illinois (1854)

In response to Stephen Douglas. Full text.

I believe each individual is naturally entitled to do as he pleases with himself and the fruit of his labor, so far as it in no wise interferes with any other man’s rights.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Chicago (10 Jul 1858)

(Source)

The people — the people — are the rightful masters of both Congresses, and courts — not to overthrow the Constitution, but to overthrow the men who pervert it.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Cooper Union, New York City (27 Feb 1860)

(Source)

On preventing the spread of slavery to new states and territories. Sometimes paraphrased, "We the people are the rightful masters of both Congress and the Courts, not to overthrow the Constitution but to overthrow the men who would pervert the Constitution."

What constitutes the bulwark of our own liberty and independence? It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling sea coasts, the guns of our war steamers, or the strength of our gallant and disciplined army. These are not our reliance against a resumption of tyranny in our fair land. All of them may be turned against our liberties, without making us stronger or weaker for the struggle. Our reliance is in the love of liberty which God has planted in our bosoms. Our defense is in the preservation of the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, every where. Destroy this spirit, and you have planted the seeds of despotism around your own doors.

It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the motherland; but something in the Declaration giving liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance. This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence.

Nearly eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for some men to enslave others is a “sacred right of self-government.” These principles cannot stand together. They are as opposite as God and Mammon; and whoever holds to the one must despise the other.

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I cannot but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our Republican example of its just influence in the world — enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites — causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty — criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.

What has occurred in this case must ever recur in similar cases. Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Washington, DC (10 Nov 1964)

(Source)

I have always found that mercy bears richer fruits than strict justice.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Washington, DC (1865)

Most commonly attributed to a speech in Washington (1865), but also recalled by Joseph Gillespie (author, long-time friend) regarding pardons for some deserters in the summer of 1864 (The Lincoln Memorial: Album-Immortelles, ed. O. Oldroyd, 1882)

When the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion, should ever be adopted. It is an old and true maxim “that aa drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall.” If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend. Therein is a drop of honey that catches his heart, which, say what you will, is the great high-road to his reason, and which, when once gained, you will find but little trouble in convincing his judgement of the justice of your cause, if indeed that cause really be a just one.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Washingtonian Temperance Society, Springfield, Illinois (22 Feb 1842)

(Source)

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

Speech, Young Men’s Lyceum, Springfield, Illinois (27 Jan 1838)

(Source)

This seems to be the source of this far more prosaic, and spurious, Lincoln quote: "America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves."

Labor is prior to, and independent of, capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) American lawyer, politician, US President (1861-65)

State of the Union address (3 Dec 1861)

(Source)