As long as we are not actually destroyed, we can work to gain greater understanding of other peoples and to try to present to the peoples of the world the values of our own beliefs. We can do this by demonstrating our conviction that human life is worth preserving and that we are willing to help others to enjoy benefits of our civilization just as we have enjoyed it. (20 December 1961)

Eleanor Roosevelt (1884–1962) First Lady of the US (1933–1945), politician, diplomat, activist

Column (1951-12-20), “My Day”

(Source)

Quotations about:

sharing

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

You could read Kant by yourself, if you wanted; but you must share a joke with someone else.

There was another man, however, called Ananias. He and his wife, Sapphira, agreed to sell a property; but with his wife’s connivance he kept back part of the proceeds, and brought the rest and presented it to the apostles.

“Ananias,” Peter said “how can Satan have so possessed you that you should lie to the Holy Spirit and keep back part of the money from the land? While you still owned the land, wasn’t it yours to keep, and after you had sold it wasn’t the money yours to do with as you liked? What put this scheme into your mind? It is not to men that you have lied, but to God.”

When he heard this Ananias fell down dead. This made a profound impression on everyone present.[Ἀνὴρ δέ τις Ἁνανίας ὀνόματι σὺν Σαπφίρῃ τῇ γυναικὶ αὐτοῦ ἐπώλησεν κτῆμα καὶ ἐνοσφίσατο ἀπὸ τῆς τιμῆς, συνειδυίης καὶ τῆς γυναικός, καὶ ἐνέγκας μέρος τι παρὰ τοὺς πόδας τῶν ἀποστόλων ἔθηκεν.

εἶπεν δὲ ὁ Πέτρος, Ἁνανία, διὰ τί ἐπλήρωσεν ὁ Σατανᾶς τὴν καρδίαν σου, ψεύσασθαί σε τὸ πνεῦμα τὸ ἅγιον καὶ νοσφίσασθαι ἀπὸ τῆς τιμῆς τοῦ χωρίου; οὐχὶ μένον σοὶ ἔμενεν καὶ πραθὲν ἐν τῇ σῇ ἐξουσίᾳ ὑπῆρχεν; τί ὅτι ἔθου ἐν τῇ καρδίᾳ σου τὸ πρᾶγμα τοῦτο; οὐκ ἐψεύσω ἀνθρώποις ἀλλὰ τῷ θεῷ.

ἀκούων δὲ ὁ Ἁνανίας τοὺς λόγους τούτους πεσὼν ἐξέψυξεν, καὶ ἐγένετο φόβος μέγας ἐπὶ πάντας τοὺς ἀκούοντας.]The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Acts 5: 1-5 [JB (1966)]

(Source)

In verses 6-11, Peter asks Sapphira about the proceeds, and she backs Ananias' story, at which point, confronted with the truth, she drops dead, too, also impressing everyone present.

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:But a certain man named Ananias, with Sapphira his wife, sold a possession, and kept back part of the price, his wife also being privy to it, and brought a certain part, and laid it at the apostles’ feet.

But Peter said, Ananias, why hath Satan filled thine heart to lie to the Holy Ghost, and to keep back part of the price of the land? Whiles it remained, was it not thine own? and after it was sold, was it not in thine own power? why hast thou conceived this thing in thine heart? thou hast not lied unto men, but unto God.

And Ananias hearing these words fell down, and gave up the ghost: and great fear came on all them that heard these things.

[KJV (1611)]There was also a man called Ananias. He and his wife, Sapphira, agreed to sell a property; but with his wife's connivance he kept back part of the price and brought the rest and presented it to the apostles.

Peter said, 'Ananias, how can Satan have so possessed you that you should lie to the Holy Spirit and keep back part of the price of the land? While you still owned the land, wasn't it yours to keep, and after you had sold it wasn't the money yours to do with as you liked? What put this scheme into your mind? You have been lying not to men, but to God.'

When he heard this Ananias fell down dead. And a great fear came upon everyone present.

[NJB (1985)]But there was a man named Ananias, who with his wife Sapphira sold some property that belonged to them. But with his wife's agreement he kept part of the money for himself and turned the rest over to the apostles.

Peter said to him, “Ananias, why did you let Satan take control of you and make you lie to the Holy Spirit by keeping part of the money you received for the property? Before you sold the property, it belonged to you; and after you sold it, the money was yours. Why, then, did you decide to do such a thing? You have not lied to people -- you have lied to God!”

As soon as Ananias heard this, he fell down dead; and all who heard about it were terrified.

[GNT (1992 ed.)]However, a man named Ananias, along with his wife Sapphira, sold a piece of property. With his wife’s knowledge, he withheld some of the proceeds from the sale. He brought the rest and placed it in the care and under the authority of the apostles.

Peter asked, “Ananias, how is it that Satan has influenced you to lie to the Holy Spirit by withholding some of the proceeds from the sale of your land? Wasn’t that property yours to keep? After you sold it, wasn’t the money yours to do with whatever you wanted? What made you think of such a thing? You haven’t lied to other people but to God!”

When Ananias heard these words, he dropped dead. Everyone who heard this conversation was terrified.

[CEB (2011)]But a man named Ananias, with the consent of his wife Sapphira, sold a piece of property; with his wife’s knowledge, he kept back some of the proceeds and brought only a part and laid it at the apostles’ feet.

“Ananias,” Peter asked, “why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back part of the proceeds of the land? While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, were not the proceeds at your disposal? How is it that you have contrived this deed in your heart? You did not lie to us but to God!”

Now when Ananias heard these words, he fell down and died. And great fear seized all who heard of it.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

And the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul: neither said any of them that ought of the things which he possessed was his own; but they had all things common. […] Neither was there any among them that lacked: for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold, and laid them down at the apostles’ feet: and distribution was made unto every man according as he had need.

[Τοῦ δὲ πλήθους τῶν πιστευσάντων ἦν καρδία καὶ ψυχὴ μία, καὶ οὐδὲ εἷς τι τῶν ὑπαρχόντων αὐτῷ ἔλεγεν ἴδιον εἶναι ἀλλ᾽ ἦν αὐτοῖς ἅπαντα κοινά. […] οὐδὲ γὰρ ἐνδεής τις ἦν ἐν αὐτοῖς· ὅσοι γὰρ κτήτορες χωρίων ἢ οἰκιῶν ὑπῆρχον, πωλοῦντες ἔφερον τὰς τιμὰς τῶν πιπρασκομένων καὶ ἐτίθουν παρὰ τοὺς πόδας τῶν ἀποστόλων, διεδίδετο δὲ ἑκάστῳ καθότι ἄν τις χρείαν εἶχεν.]

The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Acts 4: 32, 34-35 [KJV (1611)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:The whole group of believers was united, heart and soul; no one claimed for his own use anything that he had, as everything they owned was held in common. [...] None of their members was ever in want, as all those who owned land or houses would sell them, and bring the money from them, to present it to the apostles; it was then distributed to any members who might be in need.

[JB (1966)]The whole group of believers was united, heart and soul; no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, as everything they owned was held in common. [...] None of their members was ever in want, as all those who owned land or houses would sell them, and bring the money from the sale of them, to present it to the apostles; it was then distributed to any who might be in need.

[NJB (1985)]The group of believers was one in mind and heart. None of them said that any of their belongings were their own, but they all shared with one another everything they had. [...] There was no one in the group who was in need. Those who owned fields or houses would sell them, bring the money received from the sale, and turn it over to the apostles; and the money was distributed according to the needs of the people.

[GNT (1992 ed.)]The community of believers was one in heart and mind. None of them would say, “This is mine!” about any of their possessions, but held everything in common. [...] There were no needy persons among them. Those who owned properties or houses would sell them, bring the proceeds from the sales, and place them in the care and under the authority of the apostles. Then it was distributed to anyone who was in need.

[CEB (2011)]Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. [...] There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

The faithful all lived together and owned everything in common; they sold their goods and possessions and shared out the proceeds among themselves according to what each one needed.

[πάντες δὲ οἱ πιστεύοντες ἦσαν ἐπὶ τὸ αὐτὸ καὶ εἶχον ἅπαντα κοινὰ καὶ τὰ κτήματα καὶ τὰς ὑπάρξεις ἐπίπρασκον καὶ διεμέριζον αὐτὰ πᾶσιν καθότι ἄν τις χρείαν εἶχεν·]

The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Acts 2: 44-45 [JB (1966)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:And all that believed were together, and had all things common; and sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.

[KJV (1611)]And all who shared the faith owned everything in common; they sold their goods and possessions and distributed the proceeds among themselves according to what each one needed.

[NJB (1985)]All the believers continued together in close fellowship and shared their belongings with one another. They would sell their property and possessions, and distribute the money among all, according to what each one needed.

[GNT (1992 ed.)]All the believers were united and shared everything. They would sell pieces of property and possessions and distribute the proceeds to everyone who needed them.

[CEB (2011)]All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

Thare iz nothing we are more apt to parade before others, than our kares and sorrows, and thare iz nothing the world kares so little about.

[There is nothing we are more apt to parade before others, than our cares and sorrows, and there is nothing the world cares so little about.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Josh Billings’ Farmer’s Allminax, 1875-12 (1875 ed.)

(Source)

In vain do they think themselves innocent who appropriate to their own use alone those goods which God gave in common; by not giving to others that which they themselves receive, they become homicides and murderers, inasmuch as in keeping for themselves those things which would have alleviated the sufferings of the poor, we may say that they every day cause the death of as many persons as they might have fed and did not.

Gregory I (c. 540 - 604) Bishop of Rome, liturgist, Latin Father, Doctor of the Church [Gregorius I, Saint Gregory the Great, Saint Gregory the Dialogist]

(Attributed)

(Source)

Quoted in George D. Herron, Between Caesar and Jesus, ch. 4 "Christian Doctrine and Private Property" (1899).

The war on poverty is not a struggle simply to support people, to make them dependent on the generosity of others. It is a struggle to give people a chance. It is an effort to allow them to develop and use their capacities, as we have been allowed to develop and use ours, so that they can share, as others share, in the promise of this nation. We do this, first of all, because it is right that we should.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) American politician, educator, US President (1963-69)

Letter (1964-03-16), “Special Message to the Congress Proposing a Nationwide War on the Sources of Poverty”

(Source)

A book is not only a friend, it makes friends for you. When you have possessed a book with mind and spirit, you are enriched. But when you pass it on you are enriched threefold.

Henry Miller (1891-1980) American novelist

The Books in My Life, ch. 1 “They Were Alive and They Spoke to Me” (1952)

(Source)

“But whom do I treat unjustly,” you say, “by keeping what is my own?” Tell me, what is your own? What did you bring into this life? From where did you receive it? It is as if someone were to take the first seat in the theater, then bar everyone else from attending, so that one person alone enjoys what is offered for the benefit of all in common — this is what the rich do. They seize common goods before others have the opportunity, then claim them as their own by right of preemption. For if we all took only what was necessary to satisfy our own needs, giving the rest to those who lack, no one would be rich, no one would be poor, and no one would be in need.

[Καὶ ποῖον, λέγει, ἀδικῶ, μὲ τὸ νὰ κρατῶ γιὰ τoν ἐαυτόν μου αὐτὰ ποῦ μου ἀνήκουν; Ποία, εἰπέ μου, εἶναι αὐτὰ ποῦ σου ἀνήκουν; Ἀπὸ ποῦ τὰ ἔλαβες, καὶ τὰ ἔφερες στὴν ζωὴν αὐτήν; Ὅπως ἀκριβῶς κάποιος ποὺ εὑρίσκει στὸ θέατρο θέση μὲ καλὴν θέαν, ἐμποδίζει ἔπειτα τοὺς εἰσερχομένους, θεωρώντας ὡς ἰδικὸ τοῦ αὐτὸ ποὺ προορίζεται γιὰ χρῆσιν κοινήν, ἔτσι εἶναι καὶ οἱ πλούσιοι. Ἀφοῦ ἐκυρίευσαν ἐκ τῶν προτέρων τα κοινὰ ἀγαθά, τὰ ἰδιοποιοῦνται ἁπλῶς ἐπειδὴ τὰ ἐπρόλαβαν. Ἐὰν ὁ καθένας ἐκρατοῦσε ἐκεῖνο ποὺ ἀρκεῖ γιὰ τὴν ἱκανοποίηση τῶν ἀναγκῶν του, καὶ ἄφηνε τὸ περίσσευμα σ’ αὐτὸν ποὺ τὸ χρειάζεται, κανεὶς δὲν θὰ ἦταν πλούσιος, ἀλλὰ καὶ κανεὶς πτωχός.]

Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-378) Christian bishop, theologian, monasticist, Doctor of the Church [Saint Basil the Great, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας]

“I Will Tear Down My Barns [καθελῶ μου τὰς ἀποθήκας],” Sermon # 6 [tr. Schroeder (2009)]

(Source)

In C. Paul Schroeder, ed., Saint Basil on Social Justice (2009).

Grief can take care of itself, but to get the full value of a joy you must have someone to divide it with.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

Following the Equator, ch. 48, epigraph (1897)

(Source)

For a possession which is not diminished by being shared with others, if it is possessed and not shared, is not yet possessed as it ought to be possessed.

[Omnis enim res quae dando non deficit, dum habetur et non datur, nondum habetur quomodo habenda est.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

On Christian Doctrine [De Doctrina Christiana], Book 1, ch. 1 / § 1 (1.1.1) (AD 397) [tr. Shaw (1858)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Everything which does not decrease on being given away is not properly owned when it is owned and not given.

[tr. Robertson (1958)]For everything which does not give out when given away is not yet possessed in the way in which it should be possessed, while it is possessed and not given away.

[tr. Green (1995)]For if a thing is not diminished by being shared with others, it is not rightly owned if it is only owned and not shared.

[Example]

The Holy Supper is kept, indeed,

In whatso we share with another’s need;

Not what we give, but what we share, —

For the gift without the giver is bare;

Who gives himself with his alms feeds three, —

Himself, his hungering neighbor, and me.James Russell Lowell (1819-1891) American diplomat, essayist, poet

“The Vision of Sir Launfal,” Part 2, st. 8 (1848)

(Source)

Christ / the Holy Grail speaking to Sir Launfal. See Matthew 25:31-46.

Give, give, give — what is the point of having experience, knowledge, or talent if I don’t give it away? Of having stories if I don’t tell them to others? Of having wealth if I don’t share it? I don’t intend to be cremated with any of it! It is in giving that I connect with others, with the world, and with the divine.

Isabel Allende (b. 1942) Chilean-American writer

“In Giving I Connect with Others,” This I Believe series, All Things Considered, NPR (2005-04-04)

(Source)

Written as a tribute to her daughter, Paula, who died in December 1992.

We are cups, constantly and quietly being filled.

The trick is knowing how to tip ourselves over and let the beautiful stuff out.Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) American writer, futurist, fabulist

“The Secret Mind,” The Writer (1965-11)

(Source)

Reprinted in Bradbury, Zen in the Art of Writing (1990).

Sharing the food is to me more important than arguing about beliefs. Jesus, according to the gospels, thought so too.

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) English-American theoretical physicist, mathematician, futurist

“Progress in Religion,” Templeton Prize acceptance speech, Washington National Cathedral (9 May 2000)

(Source)

It’s like this: if you have one piece of cake, and you eat it, that’s fine. If you have two pieces of cake, you should probably share some with a friend. But maybe not. Occasionally we could all use two pieces of cake. But if you have a whole cake, and you eat all of it, that’s not very cool. It’s not just selfish, it’s kinda sick and unhealthy.

Patrick Rothfuss (b. 1973) American author

“Concerning Cake, Bilbo Baggins and Charity,” Blog Entry (19 Jan 2014)

(Source)

Cry with me;

for sharing tears with others is relief in hardship.[συνάλγησον, ὡς ὁ κάμνων

δακρύων μεταδοὺς ἔχει

χουφότητα μόχϑων.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Andromeda [Ανδρομέδα], frag. 119 (TGF) (412 BC)

(Source)

Nauck frag. 119, Barnes frag. 51, Musgrave frag. 22. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translation.Come, let us weep together; for the unhappy

Find social tears their poignant griefs assuage.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]

No pleasure has any taste for me when not shared with another: no happy thought occurs to me without my being irritated at bringing it forth alone with no one to offer it to.

[Nul plaisir n’a saveur pour moy sans communication. Il ne me vient pas seulement une gaillarde pensée en l’ame, qu’il ne me fasche de l’avoir produite seul, et n’ayant à qui l’offrir.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 3, ch. 9 (3.9), “Of Vanity [De la vanité]” (1587) [tr. Screech (1987)]

(Source)

First appeared in the 1588 edition.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:With me no pleasure is fully delightsome without communication and no delight absolute except imparted. I doe not so much as apprehend one rare conceipt, or conceive one excellent good thought in my minde, but me thinks I am much grieved and grievously perplexed to have produced the same alone and that I have no sympathizing companion to impart it unto.

[tr. Florio (1603)]There can be no Pleasure to me without Communication. There is not so much as a spritely Thought comes into my Mind, that it does not grieve me to have produc'd alone, and that I have no one to communicate it unto.

[tr. Cotton (1686)]There can be no pleasure to me without communication: there is not so much as a sprightly thought comes into my mind, that it does not grieve me to have produced alone, and that I have no one to communicate it to.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]No pleasure has any savour for me without imparting it; not even a lively thought comes into my mind that I am not vexed at expressing it when alone and at having no one to offer it to.

[tr. Ives (1925)]No pleasure has any savor for me without communication. Not even a merry thought comes to my mind without my being vexed at having produced it alone without anyone to offer it to.

[tr. Frame (1943)]

Books are one of the few things men cherish deeply. And the better the man, the more easily will he part with his most cherished possessions. A book lying idle on a shelf is wasted ammunition. Like money, books must be kept in constant circulation. Lend and borrow to the maximum — of both books and money. But especially books, for books represent infinitely more than money.

You ask me why I have no verses sent?

For fear you should return the compliment.[Cur non mitto meos tibi, Pontiliane, libellos?

Ne mihi tu mittas, Pontiliane, tuos.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 7, epigram 3 (7.3) (AD 92) [tr. Hay (1755)]

(Source)

Compare to Epigram 5.73. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Why send I not to thee these books of mine?

'Cause I, Pontilian, would be free from thine.

[tr. Wright (1663)]Why I send thee, Pontilian, not one of my writings?

It is lest thou, too gen'rous, return thine enditings.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), 12.10]Why do I not send you my books, Pontilianus? Lest you should send me yours, Pontilianus.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]Why, sir, I don't my verses send you,

Pray, would you have the reason known?

The reason is -- for fear, my friend, you

Should send me, in return, your own.

[tr. Webb (1879)]You ask me why I send you not my books?

Lest you should send me yours, my friend, in turn.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]I never send my books, it’s true.

Know why? You’d send me your books too.

[tr. West (1912), "Reply"]Why do I not send you my works, Pontilianus? That you, Pontilianus, may not send yours to me.

[tr. Ker (1919)]You ask me why my books were never sent?

For fear you might return the compliment.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]Pontilianus asks why I omit

To send him all the poetry that is mine;

The reason is that in return for it,

Pontilianus, thou might'st send me thine.

[tr. Duff (1929)]You ask me why I do not send you

All my latest publications?

Let in turn you send me, sir,

All your latest lucubrations!

[tr. Marcellino (1968)]Why have I never sent

My works to you, old hack?

For fear the compliment

Comes punishingly back.

[tr. Michie (1972)]Why don't I send you my little books, Pontilianus? Fore fear you might send me yours, Pontilianus.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]Why don’t I send you my little books?

Pontilianus, lest you send me yours.

[tr. Kline (2006), "No thanks"]You ask me why I send you not my book?

For fear you'll say, "Here's my work -- take a look."

[tr. Wills (2007)]Why don’t I send my books to you?

For fear you’d send me your books, too.

[tr. McLean (2014)]You wonder why my little book is overdue,

dear Pontilianus?

It’s just that I don’t want to look at one from you.

[tr. Juster (2016)]You ask me why I’ve sent you no new verses?

There might be reverses.

[tr. Burch (c. 2017)]You fret I haven’t sent you, Wade,

My latest book for free;

The fact is that I’m too afraid

You’d send your book to me.

[tr. Mitchell]

This communicating of a man’s self to his friend worketh two contrary effects; for it redoubleth joys and cutteth griefs in Halves. For there is no man that imparteth his joys to his friend, but he joyeth the more; and no man that imparteth his griefs to his friend, but that he grieveth the less.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

“Of Friendship,” Essays, No. 27 (1625)

(Source)

A thief can rifle any till,

A fire with ash your home can fill,

A creditor calls in your debt.

Bad harvest does your farm upset,

An impish mistress robs your dwelling,

Storm shatters ships with water swelling.

But gifts to friends your friendships save.

You keep thus always what you gave.[Callidus effracta nummos fur auferet arca,

Prosternet patrios impia flamma lares:

Debitor usuram pariter sortemque negabit,

Non reddet sterilis semina iacta seges:

Dispensatorem fallax spoliabit amica,

Mercibus extructas obruet unda rates.

Extra fortunam est, quidquid donatur amicis:

Quas dederis, solas semper habebis opes.]Martial (AD c.39-c.103) Spanish Roman poet, satirist, epigrammatist [Marcus Valerius Martialis]

Epigrams [Epigrammata], Book 5, epigram 42 (5.42) (AD 90) [tr. Wills (2007)]

(Source)

(Source(Latin)). Alternate translations:The crafty thefe from battered chest,

doth filch thy coine awaie:

The debter nor the interest,

nor principall will pay.

The fearefull flame destroies the goods,

and letteth nought remaine:

The barren ground for seede recevd,

restoreth naught again.

The subtle harlot naked strips

her lover to the skin:

If thou commit thy self to seas,

great danger art thou in.

Not that thou gevest to thy frend,

can fortune take away:

That onely that thou givst thy friend,

thou shalt posses for ay.

[tr. Kendall (1577)]Thieves may thy Coffers breake, steale coyne or plate;

Thy house a sudden fire may ruinate.

Debtors may Use, and Principall deny,

And dead thy seedes in barren Grounds may lye:

Thy Steward may be cheated by a Whore;

Thy Merchandise the Ocean may devour.

But what thou giv'st thy friends, from chance is free.

Thy gifts alone shall thine for ever be.

[tr. May (1629)]Some felon-hand may steal thy gold away;

Or flames destructive on thy mansion prey.

The fraudful debtor may thy loan deny;

Or blasted fields no more their fruits supply.

The am'rous steward to adorn his dear,

With spoils may deck her from thy plunder'd year.

Thy freighted vessels, ere the port they gain,

O'erwhelm'd by storms may sink beneath the main:

But what thou giv'st a friend for friendship's sake,

Is the sole wealth which fortune n'er can take.

[tr. Melmoth (c. 1750)]Thieves may break locks, and with your cash retire;

Your ancient seat may be consumed by fire;

Debtors refuse to pay you what they owe;

Or your ungrateful field the seed you sow;

You may be plundered by a jilting whore;

Your ships may sink at sea with all their store:

Who gives to friends, so much from Fate secures;

That is the only wealth for ever yours.

[tr. Hay (1755), ep. 43]The thief shall burst thy box, and slyly go:

The impious flame shall lay thy Lares low.

Thy dettor shall deny both use and sum:

Thy seed deposited may never come.

A faithless female shall they steward spoil:

They ships are swallow'd, while thy billow boil.

Whate'er is bountied, quit vain fortune's road:

Thine is alone the wealth thou has bestow'd.

[tr. Elphinston (1782), Book 5, ep. 82]A crafty thief may purloin money from a chest;

an impious flame may destroy paternal Lares;

a debtor may deny both principal and interest;

land may not yield crops in return for the seed scattered upon it;

frauds may be practices on a steward entrusted with your household purse;

the sea may overwhelm ships laden with merchandise.

Whatever is given to friends is beyond the reach of Fortune;

the wealth you have bestowed is the only wealth you can keep.

[tr. Amos (1858), ch. 3, ep. 77]A cunning thief may burst open your coffers, and steal your coin;

an impious fire may lay waste your ancestral home;

your debtor may refuse you both principal and interest;

your corn-field may prove barren, and not repay the seed you have scattered upon it;

a crafty mistress may rob your steward;

the waves may engulf your ships laden with merchandise.

But what is bestowed on your friends is beyond the reach of fortune;

the riches you give away are the only riches you will possess for ever.

[tr. Bohn's Classical (1859)]A present to a friend's beyond the reach of fortune:

That wealth alone you always will possess

Which you have given away.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]A cunning thief will break your money-box and carry off your coin,

cruel fire will lay low your ancestral home;

your debtor will repudiate interest alike and principal,

your sterile crop will not return you the seed you have sown;

a false mistress will despoil your treasurer,

the wave will overwhelm your ships stored with merchandise.

Beyond Fortune's power is any gift made to your friends;

only wealth bestowed will you possess always.

[tr. Ker (1919)]Some thief may steal your wealth away,

Although by massive walls surrounded;

Or ruthless fire in ashes lay

The ancient home your fathers founded;

A debtor may withhold your dues,

Deny perhaps a debt is owing,

Or sullen ploughlands may refuse

To yield a harvest to your sowing.

A cunning trollop of the town

May make your agent rob his master,

Or waters of the ocean drown

Your goods and ship in one disaster.

But give to friends whate'er you may,

'Tis safe from fortune's worst endeavor:

The riches that you give away,

These only shall be yours for ever.

[tr. Pott & Wright (1921)]Some cunning burglar will abstract your plate,

A godless fire your roof will devastate,

A debtor steal both interest and loan,

A barren field will turn your seed to stone.

A wily wench will strip your steward bare,

The greedy sea engulf your galleon's ware.

Give to a friend and fortune is checkmated;

Such wealth will ever as your own be rated.

[tr. Francis & Tatum (1924), #247]A cunning thief may rob your money-chest,

And cruel fire lay low an ancient home;

Debtors may keep both loan and interest;

Good seed may fruitless rot in barren loam.

A guileful mistress may your agent cheat,

And waves engulf your laden argosies;

But boons to friends can fortune's slings defeat:

The wealth you give away will never cease.

[tr. Duff (1929)]A cunning thief will break open your coffer and carry off your money, ruthless fire will lay low your family horne, your debtor will repudiate interest and principal alike, your barren fields will not return the scattered seed, a tricky mistress will rob your steward, the wave ,will overwhelm your ships piled high with merchandise: hut whatever is given to friends is beyond the grasp of Fortune. Only the wealth you give away will always be yours.

[tr. Shackleton Bailey (1993)]Deft thieves can break your locks and carry off your savings,

fire consume your home,

debtors default on principal and interest,

failed crops return not even the seed you'd sown,

cheating women run up your charge accounts,

storm overwhelm ships freighted with all your goods.

Fortune can't take away what you give your friends:

that wealth stays yours forever.

[tr. Powell (c. 2000)]The only wealth that's yours forever

is the wealth you give away.

[tr. Kennelly (2008), "Forever"]Sly thieves will smash your coffer and steal your cash;

impious flames will wreck your family home;

your debtor won't repay your loan or interest;

your barren fields will yield less than you've sown;

a crafty mistress will despoil your steward;

a wave will swamp your ships piled high with stores.

But what you give to friends is safe from Fortune:

only the wealth you give away is yours.

[tr. McLean (2014)]Savings -- the cunning thief will crack your safe and steal them;

ancestral home -- the fires don't care, they'll trash it;

the guy who owes you money -- won't pay the interest, won't pay at all.

Your field -- it's barren, sow seed and you'll get no return;

your girlfriend -- she'll con your accountant and leave you penniless;

your shipping line -- the waves will swamp your stacks of cargo.

But what you give to friends is out of fortune's reach.

The wealth you give away is the only wealth you'll never lose.

[tr. Nisbet (2015)]

If a man should ascend alone into heaven and behold clearly the structure of the universe and the beauty of the stars, there would be no pleasure for him in the awe-inspiring sight, which would have filled him with delight if he had had someone to whom he could describe what he had seen.

[Si quis in coelum ascendisset, naturamque mundi, et pulchritudinem siderum perspexisset, insuavem illam admirationem ei fore; quae jucudissima fuisset, si aliquem, cui narraret, habuisset.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Laelius De Amicitia [Laelius on Friendship], ch. 23 / sec. 88 (44 BC) [tr. Falconer (1923)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Cicero attributes this as a paraphrase of Archytas of Tarentum (d. 394 BC), a Pythagorean philosopher and astronomer. Alternate translations:If any one could have ascended to the sky, and surveyed the structure of the universe, and the beauty of the stars, that such admiration would be insipid to him; and yet it would be most delightful if he had someone to whom he might describe it.

[tr. Edmonds (1871)]If one had ascended to heaven, and had obtained a full view of the nature of the universe and the beauty of the stars, yet his admiration would be without delight, if there were no one to whom he could tell what he had seen.

[tr. Peabody (1887)]If a man could ascend to heaven and get a clear view of the natural order of the universe, and the beauty of the heavenly bodies, that wonderful spectacle would give him small pleasure, though nothing could be conceived more delightful if he had but had some one to whom to tell what he had seen.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1909)]If a man could mount to heaven and survey the mighty universe with all the planetary orbs, his admiration of its beauties would be much diminished, unless he had someone to share in his pleasure.

[Source]

What can be more delightful than to have someone to whom you can say everything with the same absolute confidence as to yourself? Is not prosperity robbed of half its value if you have no one to share your joy?

[Quid dulcius quam habere quicum omnia audeas sic loqui ut tecum? Qui esset tantus fructus in prosperis rebus, nisi haberes, qui illis aeque ac tu ipse gauderet?]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Laelius De Amicitia [Laelius on Friendship], ch. 6 / sec. 22 (44 BC) [tr. Shuckburgh (1909)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Peabody (below) attributes the first sentence here to Ennius, whom Cicero quotes in the previous sentence, but nobody else does. Alternate translations:What can be more delightful than to have one to whom you can speak on all subjects just as to yourself? Where would be the great enjoyment in prosperity if you had not one to rejoice in it equally with yourself?

[tr. Edmonds (1871)]What sweeter joy than in the kindred soul, whose converse differs not from self-communion? How could you have full enjoyment of prosperity, unless with one whose pleasure in it was equal to your own?

[tr. Peabody (1887)]What is sweeter than to have someone with whom you may dare discuss anything as if you were communing with yourself? How could your enjoyment in times of prosperity be so great if you did not have someone whose joy in them would be equal to your own?

[tr. Falconer (1923)]What is sweeter than to have someone with whom you dare to discuss everything, as if with yourself? How could there be great joy in prosperous things, if you did not have someone who would enjoy them equally much as you yourself?

[Source]

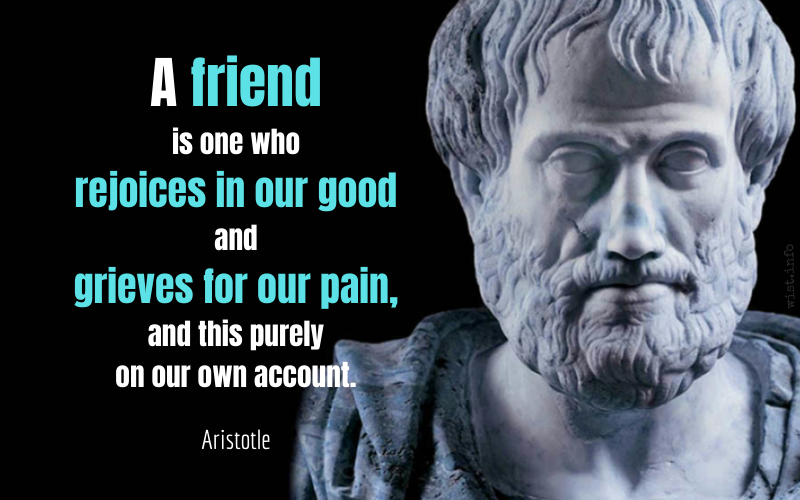

A friend is one who rejoices in our good and grieves for our pain, and this purely on our own account.

[τούτων δὲ ὑποκειμένων ἀνάγκη φίλον εἶναι τὸν συνηδόμενον τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς καὶ συναλγοῦντα τοῖς λυπηροῖς μὴ διά τι ἕτερον ἀλλὰ δι᾽ ἐκεῖνον.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Rhetoric [Ῥητορική; Ars Rhetorica], Book 2, ch. 4, sec. 3 (2.4.3) / 1381a (350 BC) [tr. Jebb (1873)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:

- "He who rejoices with one in prosperity, and sympathises with one in pain, not with a view to anything else but for his friend's sake, is a friend." [Source (1847)]

- "One who participates in another's joy at good fortune, and in his sorry at what aggrieves him, not from any other motive, but simply for his sake, is his friend." [tr. Buckley (1850)]

- "Your friend is the sort of man who shares your pleasure in what is good and your pain in what is unpleasant, for your sake and for no other reason." [tr. Roberts (1924)]

- "He is a friend who shares our joy in good fortune and our sorrow in affliction, for our own sake and not for any other reason." [tr. Freese (1926)]

- "The following people are our friends: those who share our pleasure when good things happen and our distress when bad things happen for no other reason than for our sake." [tr. Waterfield (2018)]

- "A friend is one who shares in the other fellow's pleasure at the good things and his pain at what is grievous, for no other reason than that fellow's sake." [tr. Bartlett (2019)]

- "A friend is someone who is a partner in our happiness and a partner in our sorrow not for any other reason but for friendship." [tr. @sentantiq (2019)]

Who kindly sets a wand’rer on his way

Does e’en as if he lit another’s lamp by his:

No less shines his, when he his friend’s hath lit.[Homó, qui erranti cómiter monstrát viam,

Quasi lúmen de suo lúmine accendát, facit.

Nihiló minus ipsi lúcet, cum illi accénderit.]Ennius (239-169 BC) Roman poet, writer [Quintus Ennius]

Telephus, frag 412-414 [tr. Miller (1913)]

(Source)

The fragment comes to us from Cicero, De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 1, ch. 16 / sec. 51 (44 BC). Original Latin. Alt. trans.:He that directs the wandering traveller,

Doth, as it were, light another's torch by his own;

Which gives him ne'er the less of light, for that

It gave another.

[tr. Cockman (1699)]The man who kindly points out the way to the wandering traveller, gives light to the lamp of another, without diminishing by the communication the light of his own.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]He who kindly shows the bewildered traveller the right road, does as it were light his lamp by his own; which affords none the less light to himself after it has lighted the other.

[tr. Edmonds (1865)]Who kindly shows a wanderer his way,

Lights, as it were, a torch from his own torch, --

In kindling others' light, no less he shines.

[tr. Peabody (1883)]The man who kindly points the way top a wanderer, does as though he kindles a light from the light that is his; it shines none the less for himself when he has kindled it for his fellow.

["trib Teleph. R suae lumine accendit facis Hartman, Mnemoe., XXI, 382 fortass recte"]

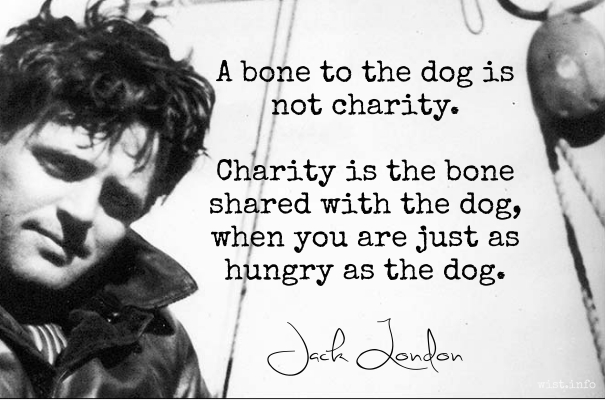

The very poor can always be depended upon. They never turn away the hungry. Time and again, all over the United States, have I been refused food at the big house on the hill; and always have I received food from the little shack down by the creek or marsh, with its broken windows stuffed with rags and its tired-faced mother broken with labor. Oh! you charity-mongers, go to the poor and learn, for the poor alone are the charitable. They neither give nor withhold from the excess. They have no excess. They give, and they withhold never, from what they need for themselves. A bone to the dog is not charity. Charity is the bone shared with the dog when you are just as hungry as the dog.

Jack London (1876-1916) American novelist

“My Life in the Underworld,” Cosmopolitan Magazine (May 1907)

(Source)

Republished in The Road, Part 1, ch. 1 (1907). Recalling his days as a hobo in 1892.

We believe in a single fundamental idea that describes better than most textbooks and any speech that I could write what a proper government should be: the idea of family, mutuality, the sharing of benefits and burdens for the good of all, feeling one another’s pain, sharing one another’s blessings — reasonably, honestly, fairly, without respect to race, or sex, or geography, or political affiliation.

If thou hast Knowledge, let others light their Candle at thine.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 2, # 1784 (1727)

(Source)

Often misattributed to Margaret Fuller or Winston Churchill, frequently in modern English, e.g., "If you have knowledge, let others light their candles at it" (or "in it" or "with it").

More discussion about this quotation:

For when many rejoice together, the joy of each one is richer: they warm themselves at each other’s flame.

[Quando enim cum multis gaudetur, et in singulis uberius est gaudium, quia fervefaciunt se et inflammantur ex alterutro.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

Confessions, Book 8, ch. 4 / ¶ 9 (8.4.9) [tr. Sheed (1943)] (c. AD 398)

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For when many joy together, each also has more exuberant joy for that they are kindled and inflamed one by the other.

[tr. Pusey (1838)]For when many rejoice together, each also has more exuberant joy; for that they are kindled and inflamed one by the other.

[ed. Shedd (1860)]For when many rejoice together, the joy of each one is the fuller in that they are incited and inflamed by one another.

[tr. Pilkington (1876)]For when many rejoice together, in each there is an overflowing joy, for they kindle themselves and are kindled by one another.

[tr. Hutchings (1890)]For, when joy is shared with many, the joy of each is richer, because they warm one another, catch fire from one another.

[tr. Bigg (1897)]For when many rejoice together the joy of each one is fuller, in that they warm one another, catch fire from each other.

[tr. Outler (1955)]For when many men rejoice together, there is a richer joy in each individual, since they enkindle themselves and they inflame one another.

[tr. Ryan (1960)]When large numbers of people share their joy in common, the happiness of each is greater because each adds fuel to the other’s flame.

[tr. Pine-Coffin (1961)]For when many people rejoice together, the joy of each individual is all the richer, since each one inflames the other and the warmth spreads throughout them all.

[tr. Warner (1963)]For when joy is shared with many, joy is fuller in each. They grow ardent and are fired each by the other.

[tr. Blaiklock (1983)]

Friendship, of itself a holy tie,

Is made more sacred by adversity.John Dryden (1631-1700) English poet, dramatist, critic

The Hind and the Panther, Part 3, l. 47 (1687)

(Source)

The actual lines read:For friendship of it self, an holy tye,

Is made more sacred by adversity.

As it is better to give than to receive, so it is better to share the fruit of one’s contemplation than merely to contemplate.

[Sicut enim maius est illuminare quam lucere solum, ita maius est contemplata aliis tradere quam solum contemplari.]

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) Italian friar, philosopher, theologian

Summa Theologica, 2a-2ae, “Treatise on the States of Life,” Q.188 “Of the Different Kinds of Religious Life” (1265-1274)

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- "Just as it is better to illuminate than merely to shine, so to pass on what one has contemplated is better than merely to contemplate."

- "Better to illuminate than merely to shine; to deliver to others contemplated truths than merely to contemplate."

- "Better to light up than merely to shine, to deliver to others contemplated truths than merely to contemplate." [Source]

- "For even as it is better to enlighten than merely to shine, so it is better to give to others the fruits of one's contemplation than merely to contemplate." [Source]

The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings. The inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965) British statesman and author

Speech, House of Commons (22 Oct 1945)

(Source)