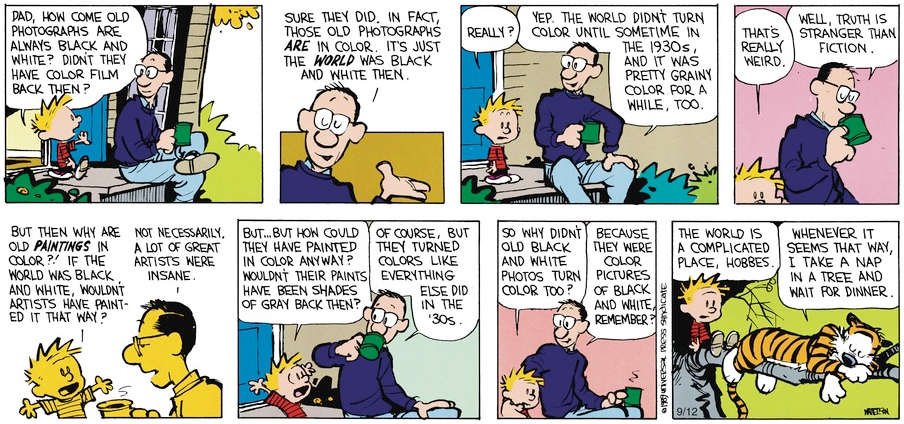

CALVIN: Dad, how come old photographs are always black and white? Didn’t they have color film back then?

CALVIN’S DAD: Sure they did. In fact, those old photographs are in color. It’s just the world was black and white then.

CALVIN: Really?

CALVIN’S DAD: Yep. The world didn’t turn color until sometime in the 1930s, and it was pretty grainy color for a while, too.

CALVIN: That’s really weird.

CALVIN’S DAD: Well, truth is stranger than fiction.

CALVIN: But then why are old paintings in color?! If the world was black and white, wouldn’t artists have painted it that way?

CALVIN’S DAD: Not necessarily. A lot of great artists were insane.

CALVIN: But … but how could they have painted in color anyway? Wouldn’t their paints have been shades of gray back then?

CALVIN’S DAD: Of course, but they turned colors like everything did in the ’30s.

CALVIN: So why didn’t old black and white photos turn color, too?

CALVIN’S DAD: Because they were color pictures of black and white, remember?

CALVIN [Later, in a tree]: The world is a complicated place, Hobbes.

HOBBES: Whenever it seems that way, I take a nap in a tree and wait for dinner.

Quotations about:

explanation

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

I will explain myself more clearly, — the Germans add, when they have explained themselves clearly.

[Ich will mich deutlicher erklären, setzen die Deutschen hinzu, wenn sie sich deutlich erklärt haben.]

Jean Paul Richter (1763-1825) German writer, art historian, philosopher, littérateur [Johann Paul Friedrich Richter; pseud. Jean Paul]

Titan, Jubilee 31, cycle 122 [Schoppe] (1803) [tr. Brooks (1863)]

(Source)

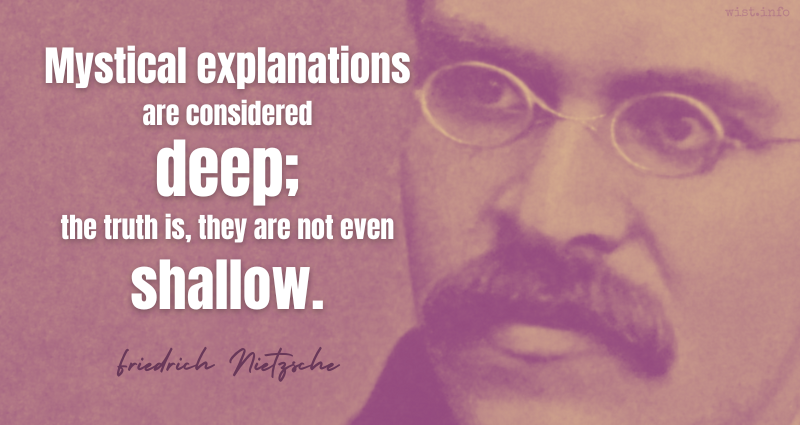

Mystical explanations are considered deep; the truth is, they are not even shallow.

[Die mystischen Erklärungen gelten für tief; die Wahrheit ist, dass sie noch nicht einmal oberflächlich sind.]

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) German philosopher and poet

The Gay Science [Die fröhliche Wissenschaft], Book 3, § 126 (1882) [tr. Nauckhoff (2001)]

(Source)

Also known as La Gaya Scienza, The Joyful Wisdom, or The Joyous Science.

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:Mystical explanations are regarded as profound; the truth is that they do not even go the length of being superficial.

[tr. Common (1911)]Mystical explanations are considered deep. The truth is that they are not even superficial.

[tr. Kaufmann (1974)]Mystical explanations are considered deep; the truth is they are not even shallow.

[tr. Hill (2018)]

Some marriages break up, and some do not, and in our world you can usually explain the former better than the latter.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Second Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 1 (1966)

(Source)

I have no desire to make mysteries, but it is impossible at the moment of action to enter into long and complex explanations.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) British writer and physician

“The Dancing Men” [Sherlock Holmes], The Strand Magazine (Dec 1903)

(Source)

Reprinted as "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" in The Return of Sherlock Holmes, ch. 3 (1905).

Even when it comes to learning, the good student contradicts his teacher and makes him more eager to explain and defend the truth. Challenge someone discreetly and his teaching will be more perfect.

[Y aun para el aprender es treta del discípulo contradecir al maestro, que se empeña con más conato en la declaración y fundamento de la verdad; de suerte que la impugnación moderada da ocasión a la enseñanza cumplida.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 213 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:In matter of learning it is a cunning fetch in the Schollar to contradict his Master, inasmuch as it lays an obligation upon him, to labour to explain the truth with greater perspicuity and solidity.) So that moderate contradiction gives him that teaches occasion to teach thoroughly.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Also in learning it is a subtle plan of the pupil to contradict the master, who thereupon takes pains to explain the truth more thoroughly and with more force, so that a moderate contradiction produces complete instruction.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]A good trick on the party of the pupil is to bait his teacher, who thereby excites himself to greater effort in the declaration, and the foundations of this beliefs, whence it comes that well-moderated debate makes for most effective teaching.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

All through history in every culture we’ve had to make up mythology to explain death to ourselves and to explain life to ourselves.

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) American writer, futurist, fabulist

“The Fantasy Makers: A Conversation with Ray Bradbury and Chuck Jones,” Interview by Mary Harrington Hall, Psychology Today (Apr 1968)

(Source)

People are entirely too disbelieving of coincidence. They are far too ready to dismiss it and to build arcane structures of extremely rickety substance in order to avoid it.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

“The Planet that Wasn’t,” The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (May 1975)

(Source)

Historians can sometimes explain, or at any rate discuss the immediate causes of some great event. Beyond that they can do little more than arrive at the platitude that every generation is, to some extent, responsible for what happened afterwards. In this way, we can finally reach the preposterous conclusion that the ancient Romans were responsible for the First World War, when they failed to civilize the Germans. This is sometimes called learning from history.

A. J. P. Taylor (1906-1990) British historian, journalist, broadcaster [Alan John Percivale Taylor]

“What Else Indeed?” New York Review of Books (5 Aug 1965)

(Source)

There probably is a God. Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn’t.

John von Neumann (1903-1957) Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, inventor, polymath [János "Johann" Lajos Neumann]

(Attributed)

(Source)

As quoted in Norman Macrae, John Von Neumann: The Scientific Genius Who Pioneered the Modern Computer, Game Theory, Nuclear Deterrence and Much More (1992).

What certainty can there be in a Philosophy which consists in as many Hypotheses as there are Phenomena to be explained. To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age. ‘Tis much better to do a little with certainty, & leave the rest for others that come after you, than to explain all things by conjecture without making sure of any thing.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) English physicist and mathematician

Opticks, Preface (unpublished) (1703)

(Source)

Artists and scientists realize that no solution is ever final, but that each new creative step points the way to the next artistic or scientific problem. In contrast, those who embrace religious revelations and delusional systems tend to see them as unshakeable and permanent.

Anthony Storr (1920-2001) English psychiatrist and author

Feet of Clay: Saints, Sinners and Madmen, Introduction (1996)

(Source)

Of all the ridiculous expressions people use — and people use a great many ridiculous expressions — one of the most ridiculous is “No news is good news.” “No news is good news” simply means that if you don’t hear from someone, everything is probably fine, and you can see at once why this expression makes such little sense because everything being fine is only one of many, many reasons why someone may not contact you. Perhaps they are tied up. Maybe they are surrounded by fierce weasels, or perhaps they are wedged tightly between two refrigerators and cannot get themselves out. The expression might as well be changed to “no news is bad news,” except that people may not be able to contact you because they have just been crowned king or are competing in a gymnastics tournament. The point is that there is no way to know why someone has not contacted you until they contact you and explain themselves. For this reason, the sensible expression would be “no news is no news,” except that it is so obvious that it is hardly an expression at all.

Several excuses are always less convincing than one.

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) English novelist, essayist and critic

Point CounterPoint, ch. 1 (1928)

(Source)

Code is like humor. When you have to explain it, it’s bad.

The difference between a conviction and a prejudice is that you can explain a conviction without getting angry.

(Other Authors and Sources)

Anonymous

No definitive source is found for this quotation. Frequently attributed to Gregory Benford, Deeper than the Darkness (1970), but it has shown up anonymously at least as early as 1951 as "filler" material in periodicals. Also sometimes attributed to Samuel Butler or Dorothy Sarnoff, but not with any citation.

All men have a reason, but not all men can give a reason.

William Ralph Inge (1860-1954) English prelate [Dean Inge]

“Implicit Reason and Explicit Reason,” St. Peter’s Day sermon, sec. 9, Oxford University (29 Jun 1840)

(Source)

I really love language; it allows us to explain the pain and the glory, the nuances and the delicacies, of our existence. Most of all, it allows us to laugh. We need language.

The mediocre teacher tells. The good teacher explains. The superior teacher demonstrates. The great teacher inspires.

William Arthur Ward (1921-1994) American aphorist, author, educator

Thoughts of a Christian Optimist (1968)

(Source)

Don’t express your ideas too clearly. Most people think little of what they understand, and venerate what they do not. […] Many praise without being able to say why. They venerate anything hidden or mysterious, and they praise it because they hear it praised.

[No allanarse sobrado en el concepto. Los más no estiman lo que entienden, lo que no perciben lo veneran. […] Alaban muchos lo que, preguntados, no saben dar razón. ¿Por qué? Todo lo recóndito veneran por misterio y lo celebran porque oyen celebrarlo.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 253 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:Not to be too intelligible. Most part do not esteem what they conceive, but admire what they understand not. [...] Many praise that which they can give no reason for, when it is asked them: because they reverence as a mystery all that is hard to be comprehended, and extoll it, by reason they hear it extolled.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Do not Explain overmuch. Most men do not esteem what they understand, and venerate what they do not see. [...] Many praise a thing without being able to tell why, if asked. The reason is that they venerate the unknown as a mystery, and praise it because they hear it praised.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]A Bit Vague. For most men have low regard for what they understand, and venerate only what is beyond them. [...] Many praise, but if asked can give no reason: Why? for they revere all that is hidden because mysterious, and they sing its praises, because they hear its praises being sung.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

People are entirely too disbelieving of coincidence. They are far too ready to dismiss it and to build arcane structures of extremely rickety substance in order to avoid it. I, on the other hand, see coincidence everywhere as an inevitable consequence of the laws of probability, according to which having no unusual coincidence is far more unusual than any coincidence could possibly be.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

“The Planet that Wasn’t,” The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (May 1975)

(Source)

Heaven will solve our problems, but not, I think, by showing us subtle reconciliations between all our apparently contradictory notions. The notions will all be knocked from under our feet. We shall see that there never was any problem.

What I mean is that if you really want to understand something, the best way is to try and explain it to someone else. That forces you to sort it out in your mind. And the more slow and dim-witted your pupil, the more you have to break things down into more and more simple ideas. And that’s really the essence of programming. By the time you’ve sorted out a complicated idea into little steps that even a stupid machine can deal with, you’ve learned something about it yourself.

NARRATOR: There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarrely inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.

Douglas Adams (1952-2001) English writer

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Phase 2, “Fit the 7th” (BBC radio) (1978-12-24)

(Source)

The Narrator then adds:There is yet a third theory which suggests that both of the first two theories were concocted by a wily editor of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy in order to increase the level of universal uncertainty and paranoia and so boost the sales of the Guide. This last theory is of course the most convincing, because The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is the only book in the whole of the known Universe to have the words DON’T PANIC inscribed in large friendly letters on the cover.

This quotation was brought back to be the epigraph for the second Hitchhiker book, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980), each paragraph on a different page:There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable.

There is another theory which states that this has already happened.

But there is one feature I notice that is generally missing in Cargo Cult Science. That is the idea that we all hope you have learned in studying science in school — we never explicitly say what this is, but just hope that you catch on by all the examples of scientific investigation. It is interesting, therefore, to bring it out now and speak of it explicitly. It’s a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty — a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid — not only what you think is right about it: other causes that could possibly explain your results; and things you thought of that you’ve eliminated by some other experiment, and how they worked — to make sure the other fellow can tell they have been eliminated.

Richard Feynman (1918-1988) American physicist

“Cargo Cult Science,” commencement address, California Institute of Technology (1974)

(Source)

What, then, is time? I know well enough what it is, provided that nobody asks me; but if I am asked what it is and try to explain, I am baffled.

[Quid est ergo tempus? Si nemo ex me quaerat, scio; si quaerenti explicare velim, nescio.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

Confessions, Book 11, ch. 14 / ¶ 17 (11.14.17) (c. AD 398) [tr. Pine-Coffin (1961)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.

[tr. Pusey (1838)]What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.

[ed. Shedd (1860)]What, then, is time? If no one ask of me, I know; if I wish to explain to him who asks, I know not.

[tr. Pilkington (1876)]What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to a questioner, I do not know.

[tr. Sheed (1943)]What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks me, I do not know.

[tr. Outler (1955)]What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to someone who does ask me, I do not know.

[tr. Ryan (1960)]What then is time? I know what it is if no one asks me what it is; but if I want to explain it to someone who has asked me, I find that I do not know.

[tr. Warner (1963)]

FLUELLEN: There is occasions and causes why and wherefore in all things.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Henry V, Act 5, sc. 1, l. 3ff (5.1.3) (1599)

(Source)