And I wanted someone who is absolutely and utterly powerful. It’s interesting because at the time, John Byrne had just taken over Superman and had announced that he was making Superman less powerful because he had become too powerful and you couldn’t write interesting stories about people that were too powerful. That started me thinking, “Well, no, actually you can, because what makes a person interesting or not interesting isn’t how powerful they are, but who they are.

Quotations by:

Gaiman, Neil

One word after another.

That’s the only way that novels get written and, short of elves coming in the night and turning your jumbled notes into Chapter Nine, it’s the only way to do it.

So keep on keeping on. Write another word and then another.Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“Pep Talk from Neil Gaiman,” National Novel Writing Month (2011)

(Source)

There’s nothing like studying the bestseller lists of bygone years for teaching an author humility. You’ve heard of the ones that got filmed, normally. Mostly you realize that today’s bestsellers are tomorrow’s forgotten things.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“This Much I Know,” The Guardian (5 Aug 2017)

(Source)

I miss what I had in terms of the speed of memory access. If I needed a word or a fact it was already at my fingertips and now it’s like an arthritic and elderly gentleman has to sit up and go down many, many flights of stairs very slowly and go and rummage in dusty drawers. Eventually he will return four days later, normally at about 1:30 in the morning, and I will sit up and go, “Oh yes! ‘Crepuscular.’ That was the word I was looking for.”

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“This Much I Know,” The Guardian (5 Aug 2017)

(Source)

Ever since I had dinner with Lou Reed I’ve tried to avoid meeting the people who would make me feel starstruck. It was a great dinner but by the end of it Lou Reed was no longer my hero, and I don’t have many heroes. I resolutely avoided meeting David Bowie, which became harder when I became friends with Duncan Jones, his son, and then got even harder when I moved to Woodstock and he lived around the corner. But I love the fact that the Bowie that I have is the Bowie in my head: a strange, evolving, absolutely fictional Bowie who became my hero when I was 11.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“This Much I Know,” The Guardian (5 Aug 2017)

(Source)

I’m convinced if I keep going one day I will write something decent. On very bad days I will observe that I must have written good things in the past, which means that I’ve lost it. But normally I just assume that I don’t have it. The gulf between the thing I set out to make in my head and the sad, lumpy thing that emerges into reality is huge and distant and I just wish that I could get them closer.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“This Much I Know,” The Guardian (5 Aug 2017)

(Source)

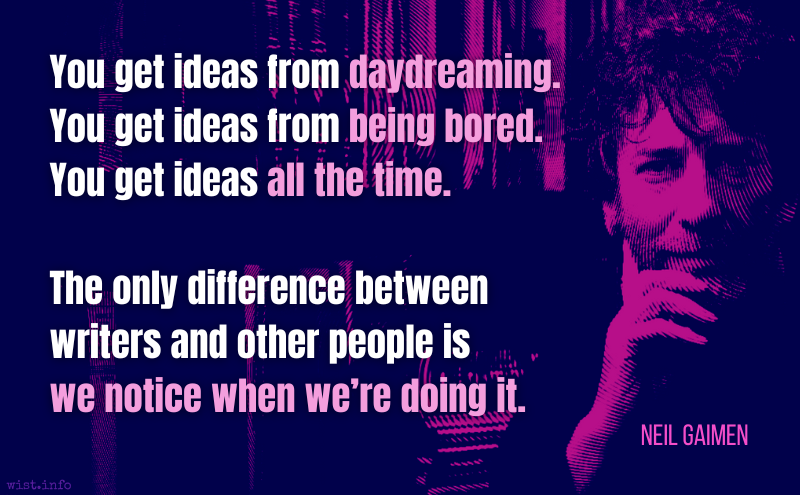

You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

“Where Do You Get Your Ideas?” (1997)

(Source)

“You’re fucked up, Mister. But you’re cool.”

“I believe that’s what they call the human condition,” said Shadow.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, Part 1, ch. 7 [Sam and Shadow] (2001)

(Source)

Later, he wondered if he could have changed things, if that gesture would have done any good, if it could have averted any of the harm that was to come. He told himself it wouldn’t. He knew it wouldn’t. But still, afterward, he wished that, just for a moment on that slow flight home, he had touched Wednesday’s hand.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, Part 2, ch. 10 (2001)

(Source)

If it makes you more comfortable, you could simply think of it as a metaphor. Religions are, by definition, metaphors, after all: God is a dream, a hope, a woman, an ironist, a father, a city, a house of many rooms, a watchmaker who left his prize chronometer in the desert, someone who loves you — even, perhaps, against all evidence, a celestial being whose only interest is to make sure your football team, army, business, or marriage thrives, prospers and triumphs over all opposition.

Religions are places to stand and look and act, vantage points from which to view the world.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, Part 3, ch. 18 (2001)

(Source)

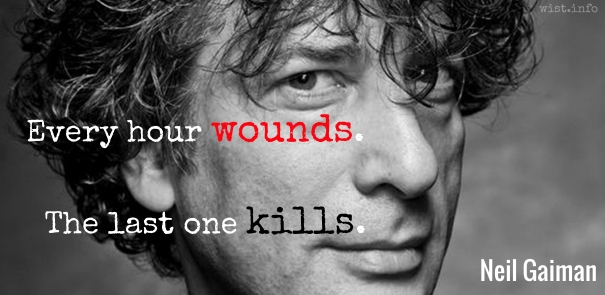

Every hour wounds. The last one kills.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, epigraph (2001)

(Source)

Gaiman notes this as an "old saying." It is frequently found on sun dials or other clocks, sometimes in Latin. Variations:

- "All hours wound; the last one kills."

- "All the hours wound you, the last one kills."

- "They all wound; the last one kills."

- "Vulnerant omnes, ultima necat."

- "Omnes vulnerant. Postuma necat."

I can believe things that are true and I can believe things that aren’t true and I can believe things where nobody knows if they’re true or not. I can believe in Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny and Marilyn Monroe and the Beatles and Elvis and Mister Ed. Listen — I believe that people are perfectible, that knowledge is infinite, that the world is run by secret banking cartels and is visited by aliens on a regular basis, nice ones who look like wrinkledy lemurs and bad ones who mutilate cattle and want our water and our women. I believe that the future sucks and I believe that the future rocks and I believe that one day White Buffalo Woman is going to come back and kick everyone’s ass. I believe that all men are just overgrown boys with deep problems communicating and that the decline of good sex in America is coincident with the decline in drive-in movie theaters from state to state. I believe that all politicians are unprincipled crooks and I still believe that they are better than the alternative. I believe that California is going to sink into the sea when the Big One comes, while Florida is going to dissolve into madness and alligators and toxic waste. I believe that antibacterial soap is destroying our resistance to dirt and disease so that one day we’ll all be wiped out by the common cold like the Martians in War of The Worlds. I believe that the greatest poets of the last century were Edith Sitwell and Don Marquis, that jade is dried dragon sperm, and that thousands of years ago in a former life I was a one-armed Siberian shaman. I believe that mankind’s destiny lies in the stars. I believe that candy really did taste better when I was a kid, that it’s aerodynamically impossible for a bumblebee to fly, that light is a wave and a particle, that there’s a cat in a box somewhere who’s alive and dead at the same time (although if they don’t ever open the box to feed it it’ll eventually just be two different kinds of dead), and that there are stars in the universe billions of years older than the universe itself. I believe in a personal god who cares about me and worries and oversees everything I do. I believe in an impersonal god who set the universe in motion and went off to hang with her girlfriends and doesn’t even know that I’m alive. I believe in an empty and godless universe of causal chaos, background noise, and sheer blind luck. I believe that anyone who says that sex is overrated just hasn’t done it properly. I believe that anyone who claims to know what’s going on will lie about the little things too. I believe in absolute honesty and sensible social lies too. I believe in a woman’s right to choose, a baby’s right to live, that while all human life is sacred there’s nothing wrong with the death penalty if you can trust the legal system implicitly, and that no one but a moron would ever trust the legal system. I believe that life is a game, that life is a cruel joke, and that life is what happens when you’re alive and that you might as well lie back and enjoy it.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, Part 2, ch. 13 [Sam] (2001)

(Source)

“Maybe,” he said. “Maybe I can get some kind of a happy ending.”

“Not only are there no happy endings,” she told him. “There aren’t even any endings.”

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

American Gods, Part 3, ch. 16 [Shadow and Bast] (2001)

(Source)

Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Coraline (2002)

Paraphrase by Gaiman of G. K. Chesterton. Gaiman included it as an epigraph, attributed to Chesterton, but without looking up the exact wording.

The Law is a blunt instrument. It’s not a scalpel. It’s a club. If there is something you consider indefensible, and there is something you consider defensible, and the same laws can take them both out, you are going to find yourself defending the indefensible.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Neil Gaiman’s Journal, “Why defend freedom of icky speech?” (1 Dec 2008)

(Source)

See Dershowitz.

“What a brain, Mister Vandemar. Keen and incisive isn’t the half of it. Some of us are so sharp,” he said as he leaned in closer to Richard, went up on tiptoes into Richard’s face, “we could just cut ourselves.”

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Neverwhere, ch. 2 [Mr. Croup] (1996)

(Source)

And Islington said nothing, but it smiled, in the manner of a cat who has not only devoured the cream and the canary, but also the chicken you were saving for dinner, and the crème brûlée that would have been dessert.

Richard looked at the woman in leather. “Is there anything, really, to be scared of?”

“Only the night on the bridge,” she said.

“The kind in armor?”

“The kind that comes when the day is over.”

Richard had noticed that events were cowards: they didn’t occur singly, but instead they would run in packs and leap out at him all at once.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Neverwhere, ch. 1 (1996; 2015 ed.)

(Source)

Richard found himself, on otherwise sensible weekends, accompanying her to places like the National Gallery and the Tate Gallery, where he learned that walking around museums too long hurts your feet, that the great art treasures of the world all blur into each other after a while, and that it is almost beyond the human capacity for belief to accept how much museum cafeterias will brazenly charge for a slice of cake and a cup of tea.

There was an old telephone in the corner of the room, an antique, two-part telephone, unused in the hospital since the 1920s, made of wood and Bakelite. Mr. Croup picked up the earpiece, which was on a long, cloth-wrapped cord, and spoke into the mouthpiece, which was attached to the base. “Croup and Vandemar,” he said, smoothly, “the Old Firm. Obstacles obliterated, nuisances eradicated, bothersome limbs removed, and tutelary dentistry.”

Richard was not dead. He was sitting in the dark, on a ledge, on the side of a storm drain, wondering what to do, wondering how much further out of his league he could possibly get. His life so far, he decided, had prepared him perfectly for a job in Securities, for shopping at the supermarket, for watching soccer on the television on the weekends, for turning up the thermostat if he got cold. It had magnificently failed to prepare him for a life as an un-person on the roofs and in the sewers of London, for a life in the cold and the wet and the dark.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Neverwhere, ch. 4 (1996)

(Source)

The above is the original US edition language. The 2006 "Author's Preferred Text" edition restores (even in the US) a few British turns of phrase that were in the original British edition (which I am fortunate enough to own).

Richard was not dead. He was sitting in the dark, on a ledge, on the side of a storm drain, wondering what to do, wondering how much further out of his depth he could possibly get. His life so far, he decided, had prepared him perfectly for a job in Securities, for shopping at the supermarket, for watching football on the telly on the weekends, for turning on a heater if he got cold. It had magnificently failed to prepare him for a life as an un-person on the roofs and in the sewers of London, for a life in the cold and the wet and the dark.

Then he smiled, like a cat who had just been entrusted with the keys to a home for wayward but plump canaries.

Richard did not believe in angels. He never had believed in angels. He was damned if he was going to start now. Still, it was much easier not to believe in something when it was not actually looking directly at you, and saying your name.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Neverwhere, ch. 9 (2006 ed.)

(Source)

In the original 1996 edition, the first two sentences are elided: "Richard did not believe in angels, he never had."

“What,” asked Mr. Croup, “do you want?”

“What,” asked the marquis de Carabas, a little more rhetorically, “does anyone want?”

“Dead things,” suggested Mr. Vandemar. “Extra teeth.”

The three of them were walking, with extreme care, along the bank of an underground river. The bank was slippery, a narrow path along dark rock and sharp masonry. Richard watched with respect as the gray water rushed and tumbled, within arm’s reach. This was not the kind of river you fell into and got out of again; it was the other kind.

The old woman took the umbrella, gratefully, and smiled her thanks. “You’ve a good heart,” she told him. “Sometimes that’s enough to see you safe wherever you go.” Then she shook her head. “But mostly, it’s not.”

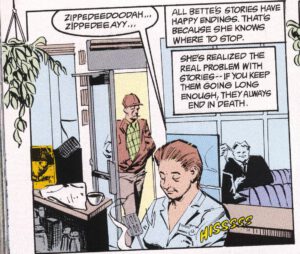

All Bette’s stories have happy endings. That’s because she knows where to stop. She’s realized the real problem with stories — if you keep them going long enough, they always end in death.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 1. Preludes and Nocturnes, # 6 “24 Hours” (1989-06)

(Source)

ROSE: “And then she woke up.” I suppose there are worse endings.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 2. The Doll’s House, # 16 “Lost Hearts” (1990)

(Source)

CYNICAL CAT: Little one, I would like to see anyone — prophet, king or God — persuade a thousand cats to do anything at the same time.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 3. Dream Country, # 18 “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” (1990-08)

(Source)

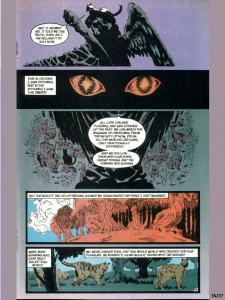

THE PROPHET: All cats can see futures, and see echoes of the past. We can watch the passage of creatures from the infinity of now, from all the worlds like ours, only fractionally different. And we follow them with our eyes, ghost things, and the humans see nothing.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 3. Dream Country, # 18 “A Dream of a Thousand Cats” (1990-08)

(Source)

DREAM: It is a fool’s prerogative to utter truths that no one else will speak.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 3. Dream Country, # 19 “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1990)

(Source)

Because the story includes William Shakespeare as a character, and is named after Shakespeare's play (which is performed in the story), this line is sometimes misattributed to Shakespeare himself.

See also this later comment by Dream.

DREAM: Things need not have happened to be true. Tales and dreams are the shadow-truths that will endure when mere facts are dust and ashes, and forgot.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 3. Dream Country, # 19 “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1990)

(Source)

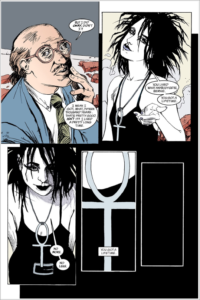

DEATH: When the first living thing existed, I was there, waiting. When the last living thing dies, my job will be finished. I’ll put the chairs on the tables, turn out the lights and lock the universe behind me when I leave.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 3. Dream Country, # 20 “Façade” (1990)

(Source)

Never a possession, always the possessor, with skin as pale as smoke, and eyes tawny and sharp as yellow wine: Desire is everything you have ever wanted. Whoever you are. Whatever you are.

Everything.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 4. Season of Mists, # 21 “A Prologue” (1990-11)

(Source)

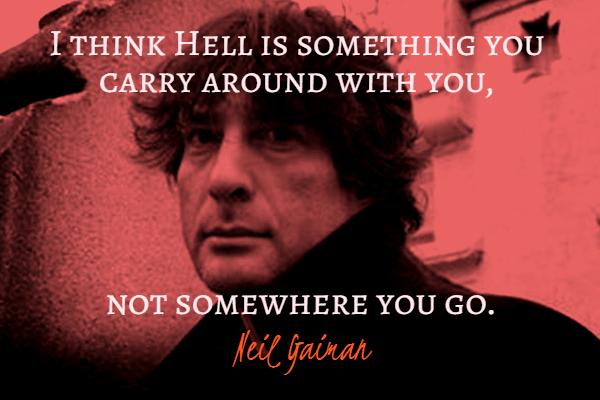

ROWLAND: I think Hell is something you carry around with you, not somewhere you go.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 4. Season of Mists, # 25 “Chapter 4” (1991-04)

(Source)

Charles Rowland to Edwin Paine (the "Dead Boy Detectives"). Paine disagrees in a following panel: "I think maybe Hell is a place. But you don't have to stay anywhere forever."

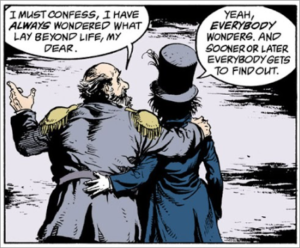

NORTON I: I must confess, I have always wondered what lay beyond life, my dear.

DEATH: Yeah, everybody wonders. And sooner or later everybody gets to find out.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 6. Fables and Reflections, # 31 “Three Septembers and a January” (1991-10)

(Source)

DREAM: It is sometimes a mistake to climb; it is always a mistake never even to make the attempt.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 6. Fables and Reflections, Vertigo Preview, “Fear of Falling” (1992-12)

(Source)

BERNIE: But I did okay, didn’t I? I mean I got, what, fifteen thousand years. That’s pretty good, isn’t it? I lived a pretty long time.

DEATH: You lived what anybody gets, Bernie. You got a lifetime. No more. No less. You got a lifetime.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 7. Brief Lives, # 43 “Part 3” (1992-11)

(Source)

INNKEEPER: Was that the truth, Cluracan?

CLURACAN: All of it except the sword-fight with the palace guard, which I threw in to add verisimilitude, excitement, and local color to an otherwise bald and insipid narrative.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 8. World’s End, # 52 “Cluracan’s Tale” (1993-08)

(Source)

THE CRONE: Can’t say I’ve ever been too fond of beginnings, myself. Messy little things. Give me a good ending any time. You know where you are with an ending.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 9. The Kindly Ones, # 57 “Chapter 1” (1993-02)

(Source)

As the eldest of the Kindly Ones (Fates, Moirai, etc.), the Crone's task, in the aspect of Atropos, is literally to cut the thread at the end of a life.

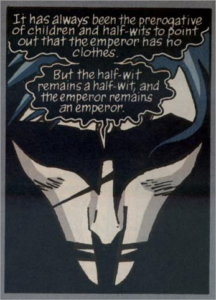

DREAM: It has always been the prerogative of children and half-wits to point out that the emperor has no clothes. But the half-wit remains a half-wit, and the emperor remains an emperor.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 9. The Kindly Ones, # 60 “The Kindly Ones: 4” (1994-06)

(Source)

ROSE: I didn’t say it was my fault. I said it was my responsibility. I know the difference.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 9. The Kindly Ones, # 60 “The Kindly Ones: 4” (1994-06)

(Source)

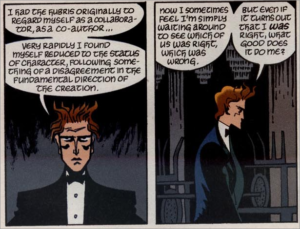

LUCIFER: I had the hubris originally to regard myself as a collaborator, as a co-author …. Very rapidly I found myself reduced to the status of character, following something of a disagreement in the fundamental direction of the Creation. Now I sometimes feel I’m simply waiting around to see which of us was right, which was wrong.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 9. The Kindly Ones, # 69 “The Kindly Ones” (1995-07)

(Source)

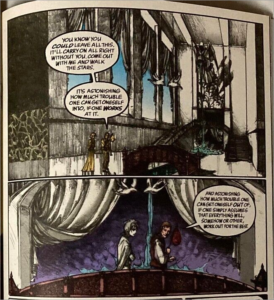

DESTRUCTION: It’s astonishing how much trouble one can get oneself into, if one works at it. And astonishing how much trouble one can get oneself out of, if one simply assumes that everything will, somehow or other, work out for the best.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 10. The Wake, # 72 “Chapter 3, In Which We Wake” (1995-11)

(Source)

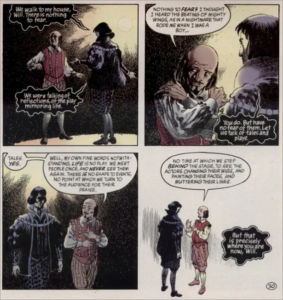

SHAKESPEARE: Well, my own fine words notwithstanding, life is no play. We meet people once, and never see them again. There is no shape to events, no point at which we turn to the audience for their praise. No time at which we step behind the stage, to see the actors changing their wigs, and painting their faces, and muttering their lines.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Sandman, Book 10. The Wake, # 75 “The Tempest” (1996-02)

(Source)

Speaking to Morpheus. Final issue of the series.

May your coming year be filled with magic and dreams and good madness. I hope you read some fine books and kiss someone who thinks you’re wonderful, and don’t forget to make some art — write or draw or build or sing or live as only you can. And I hope, somewhere in the next year, you surprise yourself.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2001-12-31), “As I Was Saying”

(Source)

Of course, when stood next to the choice of American political parties (“So, would you like Right Wing, or Supersized Right Wing with Extra Fries?”) my English fuzzy middle-of-the-roadness probably translates easily as bomb-throwing Trotskyist, but when I get to chat to proper lefties like Ken MacLeod or China Mieville I feel myself retreating rapidly back into the woffly Guardian-reading why-can’t-people-just-be-nice-to-each-otherhood of the politically out of his depth.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2003-06-15), “Walking Down the Street Naked, Possibly with a Mullet”

(Source)

When asked whether (and denying) he is a Communist.

How do you finish them? You finish them. There’s no magic answer, I’m afraid. This is how you do it: you sit down at the keyboard and you put one word after another until it’s done. It’s that easy, and that hard.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2004-05-02), “Pens, Rules, Finishing Things, and Why Stephin Merritt is not Grouchy”

(Source)

On finishing stories.

Stories may well be lies, but they are good lies that say true things, and which can sometimes pay the rent.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2004-11-17), “Politics, Portugal and No Gumbo-Limbo Trees”

(Source)

If pressed to pick a political system, I think that some country or other ought to try jury duty as a way of picking its politicians: if your name gets picked, and you can’t come up with a good enough excuse, you’ll have to give up four or five years of your life to helping run the country, which avoids the main problem of politics as I see it, which is that the kind of people you have to choose between and vote for are the kind of people who actually think that they ought to be running things. If you have a country and want to try this as a political system, let me know how it works out.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2004-11-17), “Politics, Portugal and No Gumbo-Limbo Trees”

(Source)

I think any argument that states that comics (or radio or film or a musical or the novel or insert your favourite medium here…) by its nature trivialises its subject matter is foolish, shortsighted, dim, lazy and wrong. You can say, “This is a bad comic.” You can’t say, “This is bad because it’s a comic.”

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2008-02-21), “Coraline Trailer”

(Source)

You ask, What makes it worth defending? and the only answer I can give is this: Freedom to write, freedom to read, freedom to own material that you believe is worth defending means you’re going to have to stand up for stuff you don’t believe is worth defending, even stuff you find actively distasteful, because laws are big blunt instruments that do not differentiate between what you like and what you don’t, because prosecutors are humans and bear grudges and fight for re-election, because one person’s obscenity is another person’s art. Because if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2008-12-01), “Why defend freedom of icky speech?”

(Source)

I loved coming to the US in 1992, mostly because I loved the idea that freedom of speech was paramount. I still do. With all its faults, the US has Freedom of Speech. The First Amendment states that you can’t be arrested for saying things the government doesn’t like. You can say what you like, write what you like, and know that the remedy to someone saying or writing or showing something that offends you is not to read it, or to speak out against it. I loved that I could read and make my own mind up about something.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2008-12-01), “Why defend freedom of icky speech?”

(Source)

I hope you will have a wonderful year, that you’ll dream dangerously and outrageously, that you’ll make something that didn’t exist before you made it, that you will be loved and that you will be liked, and that you will have people to love and to like in return. And, most importantly (because I think there should be more kindness and more wisdom in the world right now), that you will, when you need to be, be wise, and that you will always be kind.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2008-12-31), “Another Year”

(Source)

I’ve never been convinced that there’s any meaningful division between high culture and pop culture — I think there’s good stuff out there, and there’s stuff that’s not much good, and that Sturgeon’s Law applies to high culture and popular culture: 90% of it will be crap, which means that 10% of it will be amazing.

I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes.

Because if you are making mistakes, then you are making new things, trying new things, learning, living, pushing yourself, changing yourself, changing your world. You’re doing things you’ve never done before, and more importantly, you’re Doing Something.

So that’s my wish for you, and all of us, and my wish for myself. Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody’s ever made before. Don’t freeze, don’t stop, don’t worry that it isn’t good enough, or it isn’t perfect, whatever it is: art, or love, or work or family or life.

Whatever it is you’re scared of doing, Do it.

Make your mistakes, next year and forever.Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2011-12-31), “My New Year Wish”

(Source)

I think the most important thing I learned from Stephen King I learned as a teenager, reading King’s book of essays on horror and on writing, Danse Macabre. In there he points out that if you just write a page a day, just 300 words, at the end of a year you’d have a novel. It was immensely reassuring — suddenly something huge and impossible became strangely easy. As an adult, it’s how I’ve written books I haven’t had the time to write, like my children’s novel Coraline.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2012-04-28), “Popular Writers: A Stephen King Interview”

(Source)

Contributor's note to an interview with Stephen King, "The King and I," Sunday Times Magazine (2012-04-08).

So this is my wish, a wish for me as much as it is a wish for you: in the world to come, let us be brave — let us walk into the dark without fear, and step into the unknown with smiles on our faces, even if we’re faking them.

And whatever happens to us, whatever we make, whatever we learn, let us take joy in it. We can find joy in the world if it’s joy we’re looking for, we can take joy in the act of creation.

So that is my wish for you, and for me. Bravery and joy.Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2012-12-31), “My New Year’s Wish”

(Source)

Some years ago, I was lucky enough invited to a gathering of great and good people: artists and scientists, writers and discoverers of things. And I felt that at any moment they would realise that I didn’t qualify to be there, among these people who had really done things.

On my second or third night there, I was standing at the back of the hall, while a musical entertainment happened, and I started talking to a very nice, polite, elderly gentleman about several things, including our shared first name. And then he pointed to the hall of people, and said words to the effect of, “I just look at all these people, and I think, what the heck am I doing here? They’ve made amazing things. I just went where I was sent.”

And I said, “Yes. But you were the first man on the moon. I think that counts for something.”

And I felt a bit better. Because if Neil Armstrong felt like an imposter, maybe everyone did. Maybe there weren’t any grown-ups, only people who had worked hard and also got lucky and were slightly out of their depth, all of us doing the best job we could, which is all we can really hope for.

Go and make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious and fantastic mistakes. Break rules. Leave the world more interesting for your being here. Make. Good. Art.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Commencement address, University of the Arts, Philadelphia (2012)

(Source)

Sometimes life is hard. Things go wrong — and in life, and in love, and in business, and in friendship, and in health, and in all the other ways in which life can go wrong. And when things get tough, this is what you should do: Make good art. I’m serious. Husband runs off with a politician? Make good art. Leg crushed and then eaten by a mutated boa constrictor? Make good art. IRS on your trail? Make good art. Cat exploded? Make good art. Someone on the internet thinks what you’re doing is stupid, or evil, or it’s all been done before? Make good art.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Commencement address, University of the Arts, Philadelphia (2012)

(Source)

Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

In “Ten Rules for Writing Fiction,” The Guardian (20 Feb 2010)

(Source)

Remember that, sooner or later, before it ever reaches perfection, you will have to let it go and move on and start to write the next thing. Perfection is like chasing the horizon. Keep moving.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

In “Ten Rules for Writing Fiction,” The Guardian (20 Feb 2010)

(Source)

The main rule of writing is that if you do it with enough assurance and confidence, you’re allowed to do whatever you like. (That may be a rule for life as well as for writing. But it’s definitely true for writing.) So write your story as it needs to be written. Write it honestly, and tell it as best you can. I’m not sure that there are any other rules. Not ones that matter.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

In “Ten Rules for Writing Fiction,” The Guardian (20 Feb 2010)

(Source)

Make mistakes. Make great mistakes, make wonderful mistakes, make glorious mistakes. Better to make a hundred mistakes than to stare at a blank piece of paper too scared to do anything wrong, too scared to do anything.

How important are free speech and satire? Important enough that people will murder others to silence the kind of speech they don’t like.

Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Twitter (7 Jan 2014)

(Source)

Regarding the mass murder at the Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris.