A Fault, once denied, is twice committed.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs (compiler), # 93 (1732)

(Source)

Quotations about:

weakness

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Nobody deserves to be praised for goodness unless he is strong enough to be bad, for any other goodness is usually merely inertia or lack of will-power.

[Nul ne mérite d’être loué de bonté, s’il n’a pas la force d’être méchant: toute autre bonté n’est le plus souvent qu’une paresse ou une impuissance de la volonté.]

François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) French epigrammatist, memoirist, noble

Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales [Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims], ¶237 (1665-1678) [tr. Tancock (1959)]

(Source)

This passage was in the 1st (1665) edition, but as:Nul ne mérite d’être loué de bonté, s’il n’a la force et la hardiesse d’être méchant: toute autre bonté n’est le plus souvent qu’une paresse ou une impuissance de la mauvaise volonté.

[... if he lacks the strength and boldness to be wicked ... impotence of ill will.]

In the manuscript, the last section read:... toute autre bonté n’est en effet qu’une privation du vice, ou plutôt la timidité du vice, et son endormissement.

[... all other goodness is in fact only a deprivation of vice, or rather the timidity of vice, and its slumber.]

Compare to ¶¶ 387, 479, and 481. See also ¶169.

(Source (French)). Other translations:No Man deserves to be commended for his Vertue, who hath it not in his Power to be Wicked; all other Goodness is Generally no better than Sloth, or an Impotence in the Will.

[tr. Stanhope (1694), ¶238]None deserve the name of good, who have not spirit enough, at least, to be bad: goodness being for the most part but indolence or impotence.

[pub. Donaldson (1783), ¶197; ed. Lepoittevin-Lacroix (1797), ¶223]None deserve the character of being good, who have not spirit enough to be bad.

[ed. Carvill (1835), ¶174]No man deservers to be praised for his goodness unless he has strength of character to be wicked. All other goodness is generally nothing but indolence or impotence of will.

[ed. Gowens (1851), ¶248]No one should be praised for his goodness if he has not strength enough to be wicked. All other goodness is but too often an idleness or powerlessness of will.

[tr. Bund/Friswell (1871), ¶237]No one should be praised for benevolence if he is too weak to be wicked; most benevolence is but laziness or lack of willpower.

[tr. Heard (1917), ¶244]Goodness deserves credit only in those who are strong enough to do evil. In other cases it is usually laziness or want of character.

[tr. Stevens (1939), ¶237]No man should be praised for his goodness if he lacks the strength to be bad: in such cases goodness is usually only the effect of indolence or impotence of will.

[tr. FitzGibbon (1957), ¶237]No one deserves praise for being good who lacks the power to do evil. Goodness, for the most part, is merely laziness or absence of will.

[tr. Kronenberger (1959), ¶237]Nobody deserves to be praised for his goodness if he has not the power to be evil. All other goodness is most often but indolence or weakness of will.

[tr. Whichello (2016) ¶237]

“It is hard to be brave,” said Piglet, sniffing slightly, “when you’re only a Very Small Animal.”

A. A. Milne (1882-1956) English poet and playwright [Alan Alexander Milne]

Winnie-the-Pooh, ch. 7 “Kanga and Baby Roo Come to the Forest” (1926)

(Source)

Absolute power is partial to simplicity. It wants simple problems, simple solutions, simple definitions. It sees in complication a product of weakness — the torturous path compromise must follow.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 88 (1955)

(Source)

The weaker the man in authority, layman or cleric, the stronger his insistence that all his privileges be acknowledged.

Austin O'Malley (1858-1932) American ophthalmologist, professor of literature, aphorist

Keystones of Thought (1914)

(Source)

Thare iz more weak men in this world than thare iz wicked ones.

[There are more weak men in this world than there are wicked ones.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 281 “Variety: Bred and Butter” (1874)

(Source)

We see, by the Sketches I have given you, that all the great Kingdoms of Europe have once been free. But that they have lost their Liberties, by the Ignorance, the Weakness, the Inconstancy, and Disunion of the People. Let Us guard against these dangers, let us be firm and stable, as wise as Serpents and as harmless as Doves, but as daring and intrepid as Heroes.

John Adams (1735–1826) American lawyer, Founding Father, statesman, US President (1797–1801)

Diary (1772, Spring), “Notes for a Oration at Braintree”

(Source)

The serpents/doves reference is from the New Testament, Matthew 10:16.

There is something irreverent in the speculation, but perhaps the want of power has more to do with the wise resolutions of age than we are always willing to admit. It would be an instructive experiment to make an old man young again and leave him all his savoir. I scarcely think he would put his money in the Savings Bank after all; I doubt if he would be such an admirable son as we are led to expect; and as for his conduct in love, I believe firmly he would out-Herod Herod, and put the whole of his new compeers to the blush.

The weakness of a soul is proportionate to the number of truths that must be kept from it.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 61 (1955)

(Source)

It is always our inabilities that irritate us.

[Ce sont toujours nos impuissances qui nous irritent.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 5 “Des Passions et des Affections de l’Âme [On the Soul], ¶ 29 (1850 ed.) [tr. Calvert (1866)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Our worries always come from our weaknesses.

[tr. Attwell (1896), ¶ 65]It is always our incapacities that irritate us.

[tr. Lyttelton (1899), ch. 4, ¶ 19]It is always our inabilities that vex us.

[tr. Collins (1928), ch. 5]

Justice without strength, and strength without justice: fearful misfortunes!

[La justice sans force, et la force sans justice: malheurs aflreux!]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 15 “De la Liberté, de la Justice et des Lois [On Liberty, Justice, and Laws],” ¶ 18 (1850 ed.) [tr. Calvert (1866), ch. 12]

(Source)

A cynical habit of thought and speech, a readiness to criticise work which the critic himself never tries to perform, an intellectual aloofness which will not accept contact with life’s realities — all these are marks, not as the possessor would fain think, of superiority, but of weakness. They mark the men unfit to bear their part manfully in the stern strife of living, who seek, in the affectation of contempt for the achievements of others, to hide from others and from themselves their own weakness.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) American politician, statesman, conservationist, writer, US President (1901–1909)

Speech (1910-04-23), “Citizenship in a Republic [The Man in the Arena],” Sorbonne, Paris

(Source)

Just as dyed hair makes older men less attractive, it is what you do to hide your weaknesses that makes them repugnant.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb (b. 1960) Lebanese-American essayist, statistician, risk analyst, aphorist

The Bed of Procrustes: Philosophical and Practical Aphorisms, “Ethics” (2010)

(Source)

I am satisfied that thare iz more weakness among men than malice.

[I am satisfied that there is more weakness among men than malice.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 155 “Affurisms: Ink Lings” (1874)

(Source)

Doubtless we’re all mistaken so — ’tis true,

Each is in something a Suffenus too:

Our neighbour’s failing on his back is shown,

But we don’t see the wallet on our own.[Nimirum idem omnes fallimur, neque est quisquam

quem non in aliqua re videre Suffenum

possis. Suus cuique attributus est error,

sed non videmus manticae quod in tergo est.]Catullus (c. 84 BC – c. 54 BC) Latin poet [Gaius Valerius Catullus]

Carmina # 22 “To Varus,” ll. 18-21 [tr. Cranstoun (1867)]

(Source)

Discussing Suffenus, a prolific (but very mediocre) poet, who believes himself to be extremely clever and talented. The metaphor in the last few lines reference Aesop's fable of the two bags.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Yet all to such errors are prone, I believe;

Each man in himself a Suffenus may find:

The failings of others we quickly perceive,

But carry our own imperfection behind.

[tr. Nott (1795), # 19]Yet we are all, I doubt, in truth

Deceived like this complacent youth;

All, I am much afraid, demean us

In some one thing just like Suffenus.

For still to every man that lives

His share of errors Nature gives;

But they, as 'tis in fable sung,

Are in a bag behind us hung;

And our formation kindly lacks

The power to see behind our backs.

[tr. Lamb (1821)]Yet, which of us is there but makes

About himself as odd mistakes?

In some one thing we all demean us

Not less absurdly than Suffenus;

For vice or failing, small or great,

Is dealt to every man by fate.

But in a wallet at our back

Do we our peccadilloes pack,

And, as we never look behind,

So out of sight is out of mind.

[tr. T. Martin (1861)]Friend, 'tis the common error; all alike are wrong,

Not one, but in some trifle you shall eye him true

Suffenus; each man bears from heaven the fault they send,

None sees within the wallet hung behind, our own.

[tr. Ellis (1871)]In sooth, we all thus err, nor man there be

But in some matter a Suffenus see

Thou canst: his lache allotted none shall lack

Yet spy we nothing of our back-borne pack.

[tr. Burton (1893)]Still, we are all the same and are deceived, nor is there any man in whom you can not see a Suffenus in some one point. Each of us has his assigned delusion: but we see not what's in the wallet on our back.

[tr. Smithers (1894)]True enough, we all are under the same delusion, and there is no one whom you may not see to be a Suffenus in one thing or another. Everybody has his own fault assigned to him: but we do not see that part of the bag which hangs on our back.

[tr. Warre Cornish (1904)]After all, every man of us is deceived in the same way, nor is there any one in whom, in some trait or another, you cannot recognize a Suffenus. Every one has his weak point, but we do not see what lies in that part of our wallet which is behind our backs.

[tr. Stuttaford (1912)]Sure, all men into some such error fall,

There's a Suffenus in us one and all,

Each has his proper fault and each is blind

To the wallet's other half that hangs behind.

[tr. MacNaghten (1925)]Have we not all some faults like these?

Are we not all Suffenuses?

In others the defect we find,

But cannot see our sack behind.

[tr. Landor (c. 1926)]And we (all of us) have the same rich glow, the rapture

when writing verse. And there is no one living

who cannot find within him something of Suffenus,

each his hallucination that blinds him,

nor can he nor his sharp eyes discover

the load on his own shoulders.

[tr. Gregory (1931)]Well, we all fall this way! There's not a person

whom in some matter you can fail to see

to be Suffenus. We cart round our follies,

but cannot see the bags upon our backs.

[tr. Fraser (1961)]Conceited? Yes, but show me a man who isn't:

someone who doesn't seem like Suffenus in something.

A glaring fault? It must be somebody else's:

I carry mine in my backpack & ignore them.

[tr. C. Martin (1979)]Of course we’re all deceived in the same way, and

there’s no one who can’t somehow or other be seen

as a Suffenus. Whoever it is, is subject to error:

we don’t see the pack on our own back.

[tr. Kline (2001)]Clearly we are all deceived in the same way, nor is there anyone

Whom you could see not to be Suffenus in some thing.

To each one of us one's own mistakes have been assigned;

but we do not see the knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Drudy (1997)]Ah well, we all make that mistake -- there's not

one of us whom you can't in some small way

see as Suffenus. Each reveals his inborn flaw --

and yet we're blind to the load on our own backs!

[tr. Green (2005)]Evidently we all falter in the same way, and there is no one

whom you cannot see Suffenus in some fashion.

To each man is attributed his own error;

but we do not see the kind of knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Wikibooks (2017)]Evidently we all are deceived the same way, nor is there anyone

whom you are not able to see Suffenus in some way.

To each their own error has been assigned;

but we do not see the knapsack which is on our back.

[tr. Wikisource (2018)]

Altho’ thy Teacher act not as he preaches,

Yet ne’ertheless, if good, do what he teaches;

Good Counsel, failing Men may give; for why,

He that’s aground knows where the Shoal doth lie.

My old Friend Berryman, oft, when alive,

Taught others Thrift; himself could never thrive:

Thus like the Whetstone, many Men are wont

To sharpen others while themselves are blunt.Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1734 ed.)

(Source)

I always fear less a dull man who is naturally strong

Than someone who is weak and clever.

[ἀεὶ γὰρ ἄνδρα σκαιὸν ἰσχυρὸν φύσει

ἧσσον δέδοικα τἀσθενοῦς τε καὶ σοφοῦ.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bellerophon [Βελλεροφῶν], frag. 290 (TGF) (c. 430 BC) [tr. @sentantiq (2015)]

(Source)

Barnes frag. 51, Musgrave frag. 11. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:By far less dangerous I esteem the fool

Endued with strength of body, than the man

Who's feeble and yet wise.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]I always fear a stupid if bodily powerful man less than one who is both weak and clever.

[tr. Collard, Hargreaves, Cropp (1995)]Always I fear an unintelligent but naturally strong man less than a weak and clever one.

[tr. Stevens (2012)]I fear less the powerful but stupid

than the weak and cunning.

[Source]

It is often said that the Church is a crutch. Of course it’s a crutch. What makes you think you don’t limp?

William Sloane Coffin, Jr. (1924-2006) American minister, social activist

Credo, “The Church” (2004)

(Source)

O misery! misery! Time eats our lives,

And that dark Enemy who gnaws our hearts

Grows by the blood he sucks from us, and thrives.[Ô douleur ! ô douleur ! Le Temps mange la vie,

Et l’obscur Ennemi qui nous ronge le cœur

Du sang que nous perdons croît et se fortifie!]Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) French poet, essayist, art critic

Les Fleurs du Mal [The Flowers of Evil], # 10 “L’Ennemi [The Enemy],” st. 4 (1857) [tr. Squire (1909)]

(Source)

Also in 1861, 1868 eds. (Source (French)). Alternate translations:Oh misery! -- Time devours our lives,

And the enemy black, which consumeth our hearts

On the blood of our bodies, increases and thrives!

[tr. Scott (1909)]o grief! o grief! time eats away our lives,

and the dark Enemy gnawing at our hearts

sucks from our blood the strength whereon he thrives!

[tr. Shanks (1931)]Oh, anguish, anguish! Time eats up all things alive;

And that unseen, dark Enemy, upon the spilled

Bright blood we could not spare, battens, and is fulfilled.

[tr. Millay (1936)]Time swallows up our life, O ruthless rigour!

And the dark foe that nibbles our heart's root,

Grows on our blood the stronger and the bigger!

[tr. Campbell (1952)]Alas! Alas! Time eats away our lives,

And the hidden Enemy who gnaws at our hearts

Grows by drawing strength from the blood we lose!

[tr. Aggeler (1954)]Time and nature sluice away our lives.

A virus eats the heart out of our sides,

digs in and multiplies on our lost blood.

[tr. Lowell (1963), "The Ruined Garden"]О grief! О grief! Time eats away life,

And the dark Enemy who gnaws the heart

Grows and thrives on the blood we lose.

[tr. Fowlie (1964)]Time consumes existence pain by pain,

and the hidden enemy that gnaws our heart

feeds on the blood we lose, and flourishes!

[tr. Howard (1982)]I cry! I cry! Life feeds the seasons' maw

And that dark Enemy who gnaws our hearts

Battens on blood that drips into his jaws!

[tr. McGowan (1993)]Time eats at life: no wonder we despair.

Our enemy feeds on the blood we lose.

He gnaws our heart, and look how strong he grows.

[tr. Lerner (1999)]O pain! pain! Time devours life and the dark Enemy that gnaws our heart grows, and grows strong, from the blood we let.

[tr. Waldrop (2006)]

But, as it is in a nightmare, when sleep’s narcotic hand

Is leaden upon our eyes, we seem to be desperately trying

To run and run, but we cannot — for all our efforts, we sink down

Nerveless; our usual strength is just not there, and our tongue

Won’t work at all — we can’t utter a word or produce one sound ….[Ac velut in somnis, oculos ubi languida pressit

nocte quies, nequiquam avidos extendere cursus

velle videmur et in mediis conatibus aegri

succidimus, non lingua valet, non corpore notae

sufficiunt vires, nec vox aut verba sequuntur ….]Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

The Aeneid [Ænē̆is], Book 12, l. 908ff (12.908-912) (29-19 BC) [tr. Day-Lewis (1952)]

(Source)

How Turnus feels, in the middle of combat with Aeneas, with the nightmarish crippling of his abilities by a Fury sent from Jove.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:As when in quiet night, sleepe seiles our eye,

In vain we seeme some earnest flight to trie,

But in the midst we faint, our voice doth faile,

Nor speech, nor words, nor our known strength prevaile.

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]And as, when heavy sleep has clos'd the sight,

The sickly fancy labors in the night;

We seem to run; and, destitute of force,

Our sinking limbs forsake us in the course:

In vain we heave for breath; in vain we cry;

The nerves, unbrac'd, their usual strength deny;

And on the tongue the falt'ring accents die ....

[tr. Dryden (1697)]And as in dreams by night, when languid sleep hath closed our eyes, we seem in vain to make effort to prolong a race on which we are intent, and in midst of our efforts sink down faint; nor power is in the tongue, nor in the body competency of wonted strength, nor voice nor words obey [the dictates of our will] ....

[tr. Davidson/Buckley (1854)]E'en as in dreams, when on the eyes

The drowsy weight of slumber lies,

In vain to ply our limbs we think,

And in the helpless effort sink;

Tongue, sinews, all, their powers bely,

And voice and speech our call defy ....

[tr. Conington (1866)]And as in dreams, when languid sleep at night

Weighs down the eyelids, and in vain we strive

To run, with speed that equals our desire.

But yield, disabled, midway in our course;

The tongue, and all the accustomed forces fail.

Nor voice nor words ensue ....

[tr. Cranch (1872)]And as in sleep, when nightly rest weighs down our languorous eyes, we seem vainly to will to run eagerly on, and sink faint amidst our struggles; the tongue is powerless, the familiar strength fails the body, nor will words or utterance follow ....

[tr. Mackail (1885)]E'en as in dreaming-tide of night, when sleep, the heavy thing,

Weighs on the eyes, and all for nought we seem so helpless -- fain

Of eager speed, and faint and fail amidmost of the strain;

The tongue avails not; all our limbs of their familiar skill

Are cheated; neither voice nor words may follow from our will ....

[tr. Morris (1900)]As oft in dreams, when drowsy night doth load

The slumbering eyes, still eager, but in vain,

We strive to race along a lengthening road,

And faint and fall, amidmost of the strain;

The feeble limbs their wonted aid disdain,

Mute is the tongue, nor doth the voice obey,

Nor words find utterance ....

[tr. Taylor (1907), st. 118, l. 1054ff]But as in dreams,

when helpless slumber binds the darkened eyes,

we seem with fond desire to tread in vain

along a lengthening road, yet faint and fall

when straining to the utmost, and the tongue

is palsied, and the body's wonted power

obeys not, and we have no speech or cry ....

[tr. Williams (1910)]And as in dreams of night, when languorous sleep has weighed down our eyes, we seem to strive vainly to press on our eager course, and in mid effort sink helpless: our tongue lacks power, our wonted strength fails our limbs, nor voice nor words ensue ....

[tr. Fairclough (1918)]As in our dreams at night-time,

When sleep weighs down our eyes, we seem to be running,

Or trying to run, and cannot, and we falter,

Sick in our failure, and the tongue is thick

And the words we try to utter come to nothing,

No voice, no speech ....

[tr. Humphries (1951)]Just as in dreams of night, when languid rest

has closed our eyes, we seem in vain to wish

to press on down a path, but as we strain

we falter, weak; our tongues can say nothing,

the body loses its familiar force,

no voice, no word, can follow ....

[tr. Mandelbaum (1971), l. 1209ff]Just as in dreams when the night-swoon of sleep

Weighs on our eyes, it seems we try in vain

To keep on running, try with all our might,

But in the midst of the effort faint and fail;

Our tongue is powerless, familiar strength

Will not hold up our body, not a sound

Or word will come ....

[tr. Fitzgerald (1981), l. 1232ff]Just as when we are asleep, when in the weariness of night, rest lies heavy on our eyes, we dream we are trying desperately to run further and not succeeding, till we fall exhausted in the middle of our efforts; the tongue is useless; the strength we know we have, fails our body; we have no voice, no words to obey our will ....

[tr. West (1990)]As in dreams when languid sleep weighs down our eyes at night,

we seem to try in vain to follow our eager path,

and collapse helpless in the midst of our efforts,

the tongue won’t work, the usual strength is lacking

from our limbs, and neither word nor voice will come ....

[tr. Kline (2002)]In dreams,

When night's weariness weighs on our eyes,

We are desperate to run farther and farther

But collapse weakly in the middle of our efforts.

Our tongue doesn't work, our usual strength

Fails our body, and words will not come.

[tr. Lombardo (2005)]Just as in dreams

when the nightly spell of sleep falls heavy on our eyes

and we seem entranced by longing to keep on racing on,

no use, in the midst of one last burst of speed

we sink down, consumed, our tongue won’t work,

and tried and true, the power that filled our body

fails -- we strain but the voice and words won’t follow.

[tr. Fagles (2006), l. 1053ff]

A wise man once said, “Convention is like the shell to the chick, a protection till he is strong enough to break it through.”

Learned Hand (1872-1961) American jurist

“The Preservation of Personality,” commencement address, Bryn Mawr College (1927-06-02)

(Source)

Source of the quotation Hand references is unknown. It is often attributed directly to Hand himself.

If a man be discreet enough to take to hard drinking in his youth, before his general emptiness is ascertained, his friends invariably credit him with a host of shining qualities which, we are given to understand, lie balked and frustrated by his one unfortunate weakness.

Agnes Repplier (1855-1950) American writer

“A Plea for Humor,” Points of View (1891)

(Source)

Offered as a hypothetical sardonic observation by the author William Dean Howells.

The greatest men are connected with their own century always through some weakness.

[Die größten Menschen hängen immer mit ihrem Jahrhundert durch eine Schwachheit zuammen.]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) German poet, statesman, scientist

Elective Affinities [Die Wahlverwandtschaften], Part 2, ch. 5, “From Ottilie’s Journal [Aus Ottiliens Tagebuche]” (1809) [Niles ed. (1872)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:The greatest human beings are always linked to their century by some weakness.

[tr. Hollingdale (1971)]

You were wrong to fault my body as weak

and effete; for if I am able to reason well,

this is superior to a muscular arm.[τὸ δ᾽ἀσθενές µου καὶ τὸ θῆλυ σώµατος

κακῶς ἐµέµφθης· εἰ γὰρ εὖ φρονεῖν ἔχω,

κρεῖσσον τόδ᾽ἐστὶ καρτεροῦ βραχίονος.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Antiope [Αντιοπη], frag. 199 (TGF, Kannicht) [Amphion/ΑΜΦΙΩΝ] (c. 410 BC) [tr. Will (2015)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Barnes frag. 22, Musgrave frag. 34. Alternate translations:No right

Hast thou to censure this my frame as weak

And womanish, for if I am endued

With wisdom, that exceeds the nervous arm.

[tr. Wodhall (1809)]You were wrong to censure my weak and effeminate body;

for if I can think soundly, this is stronger than a sturdy arm.

[tr. Collard (2004)]

The noble-minded worry about their lack of ability, not about people’s failure to recognize their ability.

[君子病無能焉、不病人之不己知也]

Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 15, verse 19 (15.19) (6th C. BC – AD 3rd C.) [tr. Hinton (1998)]

(Source)

(Source (Chinese)). See also 1.16, 4.14, 14.30. Legge and other early translators numbered this, as shown below, 15.18. Alternate translations:The superior man is distressed by his want of ability. He is not distressed by men's not knowing him.

[tr. Legge (1861), 15.18]The trouble of the superior man will be his own want of ability: it will be no trouble to him that others do not know him.

[tr. Jennings (1895), 15.18]A wise and good man should be distressed that he has no ability ; he should never be distressed that men do not take notice of him.

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898), 15.18]The noble man is pained over his own incompetency, he is not pained that others ignore him.

[tr. Soothill (1910), 15.18]The proper man is irritated by his incapacities, not irritated by other people not recognizing him.

[tr. Pound (1933), 15.18]A gentleman is distressed by his own lack of capacity; he is never distressed at the failure of others to recognize his merits.

[tr. Waley (1938), 15.18]The perfect gentleman complains about his own inabilities; not about people’s ignorance of himself.

[tr. Ware (1950)]The gentleman is troubled by his own lack of ability, not by the failure of others to appreciate him.

[tr. Lau (1979)]The gentleman is pained at the lack of ability within himself; he is not pained at the fact that others do not appreciate him.

[tr. Dawson (1993)]A gentleman resents his incompetence; he does not resent his obscurity.

[tr. Leys (1997)]The gentleman worries about his incapability; he does not worry about men not knowing him.

[tr. Huang (1997)]A gentleman worries about that he does not have the ability, does not worry about that others do not understand him.

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998), #403]Exemplary persons (junzi) are distressed by their own lack of ability, not by the failure of others to acknowledge them.

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]The gentleman takes it as a fault if he is incapable of something; he does not take it as a fault if others do not know him.

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998)]The gentleman is distressed by his own inability, rather than the failure of others to recognize him.

[tr. Slingerland (2003)]The gentleman is troubled by his own lack of ability. He is not troubled by the fact that others do not understand him.

[tr. Watson (2007)]The gentleman is worried about his own lack of ability and not about the fact that others do not appreciate him.

[tr. Chin (2014)]A Jun Zi is disappointed about his own incompetency. He is not distressed that he is not known by others.

[tr. Li (2020)]

Know your major defect. Every talent is balanced by a fault, and if you give in to it, it will govern you like a tyrant.

[Conocer su defecto rey. Ninguno vive sin él, contrapeso de la prenda relevante; y si le favorece la inclinación, apodérase a lo tirano.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 225 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:To know ones prevailing fault. Every one hath one, that makes a counterpoise to his predominant perfection. And if it be backt by inclination, it rules like a Tyrant.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Know your chief fault. There lives none that has not in himself a counterbalance to his most conspicuous merit: if this be nourished by desire, it may grow to be a tyrant.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]Know your chief weakness. No one lives without some counterweight to even his greatest gift, which when petted, assumes tyranny.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

If any young Miss reads this autobiography and wants a little advice from a very old hand, I will say to her, when a man threatens to commit suicide after you have refused him, you may be quite sure he is a vain, petty fellow or a great goose; if you felt any doubts about your decision before, you need have none after this and under no circumstances must you give way. To marry a man out of pity is folly; and if you think you are going to influence the kind of fellow who has “never had a chance, poor devil,” you are profoundly mistaken. One can only influence the strong characters in life, not the weak; and it is the height of vanity to suppose that you can make an honest man of anyone.

Margot Asquith (1864-1945) British socialite, author, wit [Emma Margaret Asquith, Countess Oxford and Asquith; Margot Oxford; née Tennant]

Autobiography, Vol. 1, ch. 7 (1920)

(Source)

In a similar vein, in More or Less about Myself, ch. 5 (1934) she wrote: "It is easier to influence strong than weak characters in life."

The most dangerous men on earth are those who are afraid that they are wimps.

James Gilligan (b. c. 1936) American psychiatrist and author

Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic, ch. 3 (1997)

(Source)

When will the churches learn that intolerance, personal or ecclesiastical, is an evidence of weakness? The confident can afford to be calm and kindly; only the fearful must defame and exclude.

Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878-1969) American clergyman, author, teacher

“Tolerance,” sec. 3, Adventurous Religion (1926)

(Source)

It is the people with secret attractions to various temptations who busy themselves most with removing those temptations from other people; really they are defending themselves under the pretext of defending others, because at heart they fear their own weakness.

Ernest Jones (1879-1958) Welsh neurologist and psychoanalyst

“Criticisms of Psycho-Analytic Treatment,” Speech, Chicago Neurological and Chicago Medical Societies (18 Jan 1911)

Originally published in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences (Jul 1911). Reprinted in Papers on Psycho-Analysis, ch. 12 (1918).

The mistakes I made from weakness do not embarrass me nearly so much as those I made insisting on my strength.

James Richardson (b. 1950) American poet

“Vectors: 56 Aphorisms and Ten-second Essays,” Michigan Quarterly Review, #27 (Spring 1999)

(Source)

There is always a certain glamour about the idea of a nation rising up to crush an evil simply because it is wrong. Unfortunately, this can seldom be realized in real life; for the very existence of the evil usually argues a moral weakness in the very place where extraordinary moral strength is called for.

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) American writer, historian, social reformer [William Edward Burghardt Du Bois]

The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, ch. 12, sec. 93 (1896)

(Source)

A person who has no genuine sense of pity for the weak is missing a basic source of strength, for one of the prime moral forces that comprise greatness and strength of character is a feeling of mercy. The ruthless man, au fond, is always a weak and frightened man.

For whoever reflects on the nature of things, the various turns of life, and the weakness of human nature, grieves, indeed, at that reflection; but while so grieving he is, above all other times, behaving as a wise man: for he gains these two things by it; one, that while he is considering the state of human nature he is performing the especial duties of philosophy, and is provided with a triple medicine against adversity: in the first place, because he has long reflected that such things might befall him, and this reflection by itself contributes much towards lessening and weakening all misfortunes; and, secondly, because he is persuaded that we should bear all the accidents which can happen to a man, with the feelings and spirit of a man; and lastly, because he considers that what is blameable is the only evil; but it is not your fault that something has happened to you which it was impossible for man to avoid.

[Neque enim qui rerum naturam, qui vitae varietatem, qui imbecillitatem generis humani cogitat, maeret, cum haec cogitat, sed tum vel maxime sapientiae fungitur munere. Utrumque enim consequitur, ut et considerandis rebus humanis proprio philosophiae fruatur officio et adversis casibus triplici consolatione sanetur: primum quod posse accidere diu cogitavit, quae cogitatio una maxime molestias omnes extenuat et diluit; deinde quod humana humane ferenda intelligit; postremo quod videt malum nullum esse nisi culpam, culpam autem nullam esse, cum id, quod ab homine non potuerit praestari, evenerit.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Tusculan Disputations [Tusculanae Disputationes], Book 3, ch. 16 (3.16) / sec. 34 (45 BC) [tr. Yonge (1853)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For he that considers the order of Nature, and the Vicissitudes of Life, and the Frailty of Mankind is not melancholly when he considers these things, but is then most principally imploy'd in the exercise of Wisdom, for he reaps a double advantage; both that in the consideration of man's circumstances, he enjoyeth the proper Office of Philosophy; and in case of Adversity, he is supported by a threefold Consolation. First, that he hath long consider'd that such accidents might come; which consideration alone doth most weaken and allay all Afflictions. Then he cometh to learn, that all Tryals common to men, should be born, as such, patiently. Lastly, that he perceiveth there is no Evil, but where is blame; but there is no blame, when that falls out, the Prevention of which, was not in man to warrant.

[tr. Wase (1643)]For whoever reflects on the nature of things, the various turns of life, the weakness of human nature, grieves indeed at that reflection; but that grief becomes him as a wise man, for he gains these two points by it; when he is considering the state of human nature he is enjoying all the advantage of philosophy, and is provided with a triple medicine against adversity. The first is, that he has long reflected that such things might befall him, which reflection alone contributes much towards lessening all misfortunes: the next is, that he is persuaded, that we should submit to the condition of human nature: the last is, that he discovers what is blameable to be the only evil. But it is not your fault that something lights on you, which it was impossible for man to avoid.

[tr. Main (1824)]For neither does he who contemplates the nature of things, the mutations of life, the fragility of man, grieve when he thinks of these matters, but then most especially exercises the office of wisdom. For, by the study of human affairs, he at once pursues the proper aim of philosophy, and provides himself with a triple consolation for adverse events: -- first, that he has long deemed them possible to arrive; which one consideration has the greatest efficacy for the extenuation and mitigation of all misfortune: and, next, he perceives that human accidents are to be borne like a man: and, finally, because he sees there is no evil but fault, and that there is no fault where that has happened which man could not have prevented.

[tr. Otis (1839)]Indeed, he who thinks of the nature of things, of the varying fortune of life, of the weakness of the human race, does not sorrow when these things are on his mind, but he then most truly performs the office of wisdom; for from such thought there are two consequences, -- the one, that he discharges the peculiar function of philosophy; the other, that in adversity he has the curative aid of a threefold consolation: first, because, as he has long thought what may happen, this sole thought is of the greatest power in attenuating and diluting every trouble; next, because he understands that human fortunes are to be borne in a way befitting human nature; -- lastly, because he sees that there is no evil but guilt, while there is no guilt in the happening of what man could not have prevented.

[tr. Peabody (1886)]For the person who reflects on the nature of things, on the variety of life, and the precarity of human existence is not sad in considering these things but is carrying out the duty of wisdom in the fullest way. For they pursue both in enjoying the particular harvest of philosophy by considering what happens in human life and in suffering adverse outcomes by cleansing with a three-part solace. First, by previously accepting the possibility of misfortune—which is the most way of weakening and managing any annoyance and second, by learning that human events must be endured humanely; and third, by recognizing that there is nothing evil except for blame and there is no blame when the event is something against which no human can endure.

[tr. @sentantiq (2021)]

Both Christianity and alcohol have the power to convince us that what we previously thought deficient in ourselves and the world does not require attention; both weaken our resolve to garden our problems; both deny us the chance to fulfilment.

Alain de Botton (b. 1969) Swiss-British author

The Consolations of Philosophy, ch. 6 “Consolation for Difficulties” (sec. 19) (2000)

(Source)

Sometimes attributed to, but actually summarizing, Friedrich Nietzsche, who himself wrote of "the two great European narcotics, alcohol and Christianity" (Twilight of the Idols, "Things the Germans Lack" (sec. 2) (1888) [tr. Ludovici]).

However rationalized it may be, censorship is always an attack on human intelligence and imagination and is always a sign of weakness, not strength, in those who enforce it.

Northrop Frye (1912-1991) Canadian literary critic and literary theorist

“Introduction to Canadian Literature,” #14 (1988)

(Source)

When the weak want to give an impression of strength they hint meaningfully at their capacity for evil. It is by its promise of a sense of power that evil often attracts the weak.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 91 (1955)

(Source)

Our strength is often composed of the weakness that we’re damned if we’re going to show.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Second Neurotics Handbook, ch. 10 (1966)

(Source)

It is often said that governing is the art of compromise. But this is not a statement about governing; it is rather about the values of democracy. Legislating in the common interest means not confusing one’s own values with the common values. It requires giving equal weight to values that one does not share. But too often, commitment to this principle appears weak — a failure to stand by one’s principles.

Jason Stanley (b. 1969) American philosopher, epistemologist, academic

“Democracy and the Demagogue,” New York Times (12 Oct 2015)

(Source)

The dread of being duped by other nations — the notion that foreign heads are more able, though at the same time foreign hearts are less honest than our own, has always been one of our prevailing weaknesses.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) English jurist and philosopher

Principles of International Law, Essay 4 “A Plan for Universal and Perpetual Peace” (1796-89)

(Source)

The hard line, which has always been arguable in theory and which has had some success in practice, views the imperatives of the cold war as an ineluctable challenge, has encouraged a skeptical view of the limits of negotiation, and has placed its primary trust in ample reserves of strength.

The pseudo-conservative line is distinguishable from this not alone in being more crusade-minded and more risk-oriented in its proposed policies but also in its conviction that those who place greater stress on negotiation and accommodation are either engaged in treasonable conspiracy (the Birch Society’s view) or are guilty of well-nigh criminal failings in moral and intellectual fiber (Goldwater’s).Richard Hofstadter (1916-1970) American historian and intellectual

“Goldwater and Pseudo-Conservative Politics,” sec. 4 (1965)

(Source)

And power must ne’er be yielded to a woman.

For if we must succumb, ’twere better far

To crouch before a man; and thus at least

No one could taunt us with a woman’s rule.Sophocles (496-406 BC) Greek tragic playwright

Antigone, l. 679ff [Creon] (441 BC) [tr. Donaldson (1848)]

(Source)

Alternate translations:And yield to title to a woman's will.

Better, if needs be, men should cast us out

Than hear it said, a woman proved his match.

[tr. Campbell (1873)]And not go down before a woman's will.

Else, if I fall, 'twere best a man should strike me;

Lest one should say, 'a woman worsted him.'

[tr. Storr (1859)]And in no way can we let a woman defeat us. It is better to fall from power, if it is fated, by a man's hand, than that we be called weaker than women.

[tr. Jebb (1891)]We will not yield

To a weak woman; if we must submit,

At least we will be conquered by a man,

Nor by a female arm thus fall inglorious.

[tr. Werner (1892)]In no wise suffer a woman to worst us. Better to fall from power, if we must, by a man's hand; then we should not be called weaker than a woman.

[tr. Jebb (1917)]And no woman shall seduce us. If we must lose,

Let's lose to a man, at least! Is a woman stronger than we?

[tr. Fitts/Fitzgerald (1939), ll. 539-40]... not let myself be beaten by a woman.

Better, if it must happen, that a man

should overset me.

I won't be called weaker than womankind.

[tr. Wyckoff (1954)]We must not be

Defeated by a woman. Better far

Be overthrown, if need be, by a man

Than to be called the victim of a woman.

[tr. Kitto (1962)]Never let some woman triumph over us.

Better to fall from power, if fall we must,

at the hands of a man -- never be rated

inferior to a woman, never.

[tr. Fagles (1982)]And there must be no surrender to a woman.

No! If we call, better a man should take us down.

Never say that a woman bested us!

[tr. Woodruff (2001), l. 669 ff]Defeat by a woman must never happen.

It is better, if it is bound to happen, to be expelled by a man.

We could not be called "defeated by women" -- could not.

[tr. Tyrell/Bennett (2002), l. 678ff]Under no circumstances must he allow a woman to defeat him. It would be best -- if needs be -- to be defeated by a man, rather then allow it to be said that women have taken over.

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]And never let some woman beat us down.

If we must fall from power, let that come

at some man's hand -- at least, we won't be called

inferior to any woman.

[tr. Johnston (2005), l. 770ff]

He [the pseudo-conservative] sees his own country as being so weak that it is constantly about to fall victim to subversion; and yet he feels that it is so all-powerful that any failure it may experience in getting its own way in the world … cannot possibly be due to its limitations but must be attributed to its having been betrayed.

Richard Hofstadter (1916-1970) American historian and intellectual

“The Pseudo-Conservative Revolt” (1954)

(Source)

Bragging is not merely designed to impress. Bragging is designed to produce envy and assert superiority. It is, therefore, an act of hostility. Bragging is also a transparent ploy. It reveals your lack of self-confidence. “I am not enough,” you feel. So you resort to showering me with your “achievements,” in order to mask your perceived deficiencies.

Aaron Hass (contemp.) American clinical psychiatrist, academic, author

Doing the Right Thing: Cultivating Your Moral Intelligence, Sec. 1, ch. 7 “Self-Control” (1998)

(Source)

CHORUS [LEADER]:

Ye Children of Man! whose life is a span,

Protracted with sorrow from day to day,

Naked and featherless, feeble and querulous,

Sickly, calamitous creatures of clay![ἄγε δὴ φύσιν ἄνδρες ἀμαυρόβιοι, φύλλων γενεᾷ προσόμοιοι,

ὀλιγοδρανέες, πλάσματα πηλοῦ, σκιοειδέα φῦλ᾽ ἀμενηνά,

ἀπτῆνες ἐφημέριοι ταλαοὶ βροτοὶ ἀνέρες εἰκελόνειροι]Aristophanes (c. 450-c. 388 BC) Athenian comedic playwright

The Birds, ll. 685-687 (414 BC) [tr. Frere (1839)]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- "Come now, ye men, in nature darkling, like to the race of leaves, of little might, figures of clay, shadowy feeble tribes, wingless creatures of a day, miserable mortals, dream-like men." [tr. Hickie (1853)]

- "Weak mortals, chained to the earth, creatures of clay as frail as the foliage of the woods, you unfortunate race, whose life is but darkness, as unreal as a shadow, the illusion of a dream." [tr. O'Neill (1938)]

- "Come, ye of mortal mould, whose life is spent in darkness, ye who are like to the race of leaves, ye that are weak in action, ye images of clay, ye feeble shadowy tribes, ye wingless creatures of a day, ye miserable mortals, ye men like unto the stuff which dreams are made of ...." [tr. Warter (1830)]

- "Now then, ye men by nature just faintly alive, like to the race of leaves, do-littles, artefacts of clay, tribes shadowy and feeble, wingless ephemerals, suffering mortals, dreamlike people ...." [tr. Henderson (1998)]

- "Ye men who are dimly existing below, who perish and fade as the leaf, / Pale, woebegone, shadowlike, spiritless folk, life feeble and wingless and brief, / Frail castings in clay, who are gone in a day, like a dream full of sorrow and sighing ...." [tr. Rogers (1906)]

When the lambs is lost in the mountain, he said. They is cry. Sometime come the mother. Sometime the wolf.

Cormac McCarthy (1933-2023) American novelist, playwright, screenwriter

Blood Meridian, ch. 5 (1985)

(Source)

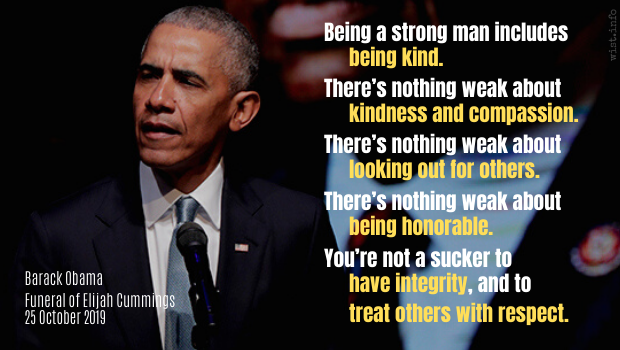

I was thinking I’d want my daughters to know how much I love them, but I’d also want them to know that being a strong man includes being kind. That there’s nothing weak about kindness and compassion. There’s nothing weak about looking out for others. There’s nothing weak about being honorable. You’re not a sucker to have integrity, and to treat others with respect.

Barack Obama (b. 1961) American politician, US President (2009-2017)

Speech, Funeral of Elijah Cummings, Washington, DC (25 Oct 2019)

(Source)

In our judgment of men, we are to beware of giving any great importance to occasional acts. By acts of occasional virtue weak men endeavour to redeem themselves in their own estimation, vain men to exalt themselves in that of mankind.

Henry Taylor (1800-1886) English dramatist, poet, bureaucrat, man of letters

The Statesman: An Ironical Treatise on the Art of Succeeding, ch. 3 (1836)

(Source)

Again, it is proper to the magnanimous person to ask for nothing, or hardly anything, but to help eagerly. When he meets people with good fortune or a reputation for worth, he displays his greatness, since superiority over them is difficult and impressive, and there is nothing ignoble in trying to be impressive with them. But when he meets ordinary people, he is moderate, since superiority over them is easy, and an attempt to be impressive among inferiors is as vulgar as a display of strength against the weak.

[μεγαλοψύχου δὲ καὶ τὸ μηδενὸς δεῖσθαι ἢ μόλις, ὑπηρετεῖν δὲ προθύμως, καὶ πρὸς μὲν τοὺς ἐν ἀξιώματι καὶ εὐτυχίαις μέγαν εἶναι, πρὸς δὲ τοὺς μέσους μέτριον: τῶν μὲν γὰρ ὑπερέχειν χαλεπὸν καὶ σεμνόν, τῶν δὲ ῥᾴδιον, καὶ ἐπ᾽ ἐκείνοις μὲν σεμνύνεσθαι οὐκ ἀγεννές, ἐν δὲ τοῖς ταπεινοῖς φορτικόν, ὥσπερ εἰς τοὺς ἀσθενεῖς ἰσχυρίζεσθαι.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Nicomachean Ethics [Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια], Book 4, ch. 3 (4.3.26) / 1124b.18 (c. 325 BC) [tr. Irwin (1999)]

(Source)

The core word Aristotle is using is μεγαλοψυχία (translated variously as high-mindedness, great-mindedness, pride, great-soulness, magnanimity). (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Further, it is characteristic of the Great-minded man to ask favours not at all, or very reluctantly, but to do a service very readily; and to bear himself loftily towards the great or fortunate, but towards people of middle station affably; because to be above the former is difficult and so a grand thing, but to be above the latter is easy; and to be high and mighty towards the former is not ignoble, but to do it towards those of humble station would be low and vulgar; it would be like parading strength against the weak.

[tr. Chase (1847)]It would seem, too, that the high-minded man asks favours of no one, or, at any rate, asks them with the greatest reluctance, but that he is always eager to do good offices to others; and that towards those in high position and prosperity he bears himself with pride, but towards ordinary men with moderation; for in the former case it is difficult to show superiority, and to do so is a lordly mater; whereas in the latter case it is easy. To be haughty among the great is no proof of bad breeding, but haughtiness among the lowly is as base-born a thing as it is to make trial of great strength upon the weak.

[tr. Williams (1869)]It is characteristic too of the high-minded man that he never, or hardly ever, asks a favor, that he is ready to do anybody a service, and that, although his bearing is stately towards person of dignity and affluence, it is unassuming toward the middle class; for while it is a difficult and dignified thing to be superior to the former, it is easy enough to be superior to the latter, and while a dignified demeanour in dealing with the former is a mark of nobility, it is a mark of vulgarity ind ealing with the latter, as it like a display of physical strength at the expense of an invalid.

[tr. Welldon (1892), ch. 8]It is characteristic of the high-minded man, again, never or reluctantly to ask favours, but to be ready to confer them, and to be lofty in his behaviour to those who are high in station and favoured by fortune, but affable to those of the middle ranks; for it is a difficult thing and a dignified thing to assert superiority over the former, but easy to assert it over the latter. A haughty demeanour in dealing with the great is quite consistent with good breeding, but in dealing with those of low estate is brutal, like showing off one’s strength upon a cripple.

[tr. Peters (1893)]It is a mark of the proud man also to ask for nothing or scarcely anything, but to give help readily, and to be dignified towards people who enjoy high position and good fortune, but unassuming towards those of the middle class; for it is a difficult and lofty thing to be superior to the former, but easy to be so to the latter, and a lofty bearing over the former is no mark of ill-breeding, but among humble people it is as vulgar as a display of strength against the weak.

[tr. Ross (1908)]It is also characteristic of the great-souled man never to ask help from others, or only with reluctance, but to render aid willingly; and to be haughty towards men of position and fortune, but courteous towards those of moderate station, because it is difficult and distinguished to be superior to the great, but easy to outdo the lowly, and to adopt a high manner with the former is not ill-bred, but it is vulgar to lord it over humble people: it is like putting forth one's strength against the weak.

[tr. Rackham (1934)]It is also characteristic of a great-souled person to ask for nothing or hardly anything but to offer his services eagerly, and to exhibit his greatness to those with a reputation for great worth or those who are enjoying good luck, but to moderate his greatness to those in the middle. For it is a difficult and a dignified thing to show oneself superior to the former, but an easy one to do so to the latter, and, while adopting a dignified manner toward the former is not ill-bred, to do so toward humble people is vulgar, like displaying strength against the weak.

[tr. Reeve (1948)]It is the mark of a high-minded man, too, never, or hardly ever, to ask for help, but to be of help to others readily, and to be dignified with men of high position or of good fortune, but unassuming with those of middle class, for it is difficult and impressive to be superior to the former, but easy to be so to the latter; and whereas being impressive to the former is not a mark of a lowly man, being so to the humble is crude -- it is like using physical force against the physically weak.

[tr. Apostle (1975)]Another mark of the magnanimous man is that he never, or only reluctantly, makes a request, whereas he is eager to help others. He his haughty toward those who are influential and successful, but moderate toward those who have an intermediate position in society, because in the former case to be superior is difficult and impressive, but in the latter it is easy' and to create an impression at the expense of the former is not ill-bred, but to do so among the humble is vulgar.

[tr. Thomson/Tredennick (1976)]It is also characteristic of a great-souled person to ask for nothing, or almost nothing, but to help others readily; and to be dignified in his behavior towards people of distinction or the well-off, but unassuming toward people at the middle level. Superiority over the first group is difficult and impressive, but over the second it is easy, and attempting to impress the first group is not ill-bred, while in the case of humble people it is vulgar, like a show of strength against the weak.

[tr. Crisp (2000)]It belongs to the great-souled also to need nothing, or scarcely anything, but to be eager to be of service, and to be great in the presence of people of worth and good fortune, but measured toward those of a middling rank. For it is a difficult and august thing to be superior among the fortunate, but easy to be that way among the middling sorts; and to exalt oneself among the former is not a lowborn thing, but to do so among the latter is crude, just as is using one's strength against the weak.

[tr. Bartlett/Collins (2011)]

Sometimes paraphrased:It is not ill-bred to adopt a high manner with the great and the powerful, but it is vulgar to lord it over humble people.

‘Tis no Sin to be tempted, but to be overcome.

William Penn (1644-1718) English writer, philosopher, politician, statesman

Some Fruits of Solitude, #450 (1693)

(Source)

See Shakespeare.

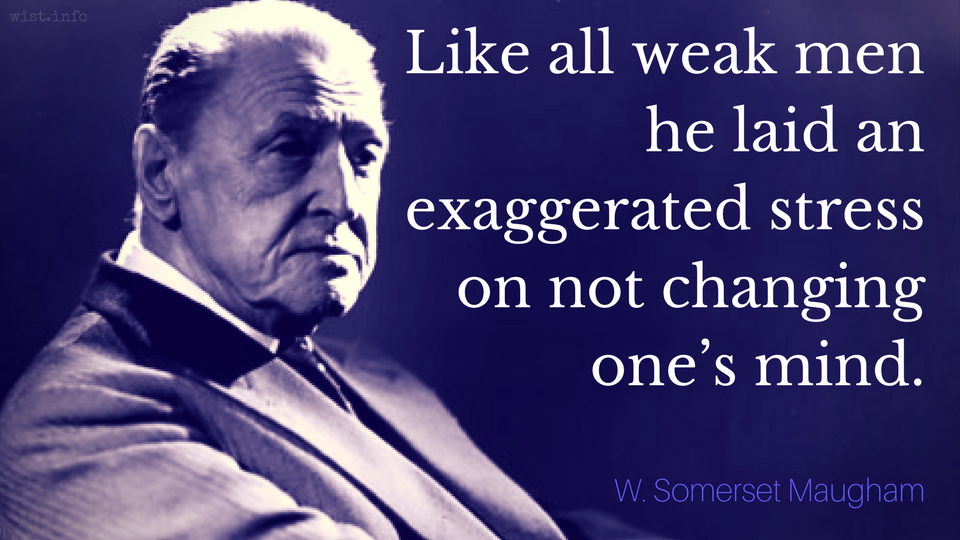

The Vicar of Blackstable would have nothing to do with the scheme which Philip laid before him. He had a great idea that one should stick to whatever one had begun. Like all weak men he laid an exaggerated stress on not changing one’s mind.

W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) English novelist and playwright [William Somerset Maugham]

Of Human Bondage, ch. 39 (1915)

(Source)

Blessed is he who has never been tempted; for he knows not the frailty of his rectitude.

Christopher Morley (1890-1957) American journalist, novelist, essayist, poet

Inward Ho!, ch. 1 (1923)

(Source)

There is nothing softer and weaker than water.

And yet there is nothing better for attacking hard and strong things.

For this reason there is no substitute for it.

All the world knows that the weak overcomes the strong and the soft overcomes the hard.

But none can practice it.

Nay, number (itself) in armies importeth not much, where the people is of weak courage; for (as Virgil saith) It never troubles a wolf how many the sheep be.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) English philosopher, scientist, author, statesman

Essays or Counsels Civil and Moral, No. 29 “Of the True Greatness of Kingdoms and Estates” (1612)

(Source)

The wolf reference is actually a common Latin proverb: "Non curat numerum lupus [The wolf doesn't care about the number]," or its longer form "Lupus non curat numerum ovium" [The wolf does not care about the number of sheep.].

Though Bacon explicitly notes the phrase in Virgil's Eclogues, the Latin saying is often attributed to Bacon.

The folly which we might have ourselves committed is the one which we are least ready to pardon in another.

Joseph Roux (1834-1886) French Catholic priest

Meditations of a Parish Priest: Thoughts, Part 4, #85 (1886)

(Source)

Although men are accused of not knowing their own weakness, yet perhaps as few know their own strength. It is in men as in soils, where sometimes there is a vein of gold, which the owner knows not of.

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) English writer and churchman

“Thoughts on Various Subjects” (1706)

(Source)

It would be some time before I fully realized that the United States sees little need for diplomacy; power is enough. Only the weak rely on diplomacy. This is why the weak are so deeply concerned with the democratic principle of the sovereign equality of states, as a means of providing some small measure of equality for that which is not equal in fact. Coming from a developing country, I was trained extensively in international law and diplomacy and mistakenly assumed that the great powers, especially the United States, also trained their representatives in diplomacy and accepted the value of it. But the Roman Empire had no need for diplomacy. Nor does the United States. Diplomacy is perceived by an imperial power as a waste of time and prestige and a sign of weakness.

The question [is] asked, “Is it common for a nation to obtain a redress of wrongs by war?” The answer to this question you will of course draw from history. In the meantime, reason will answer it on grounds of probability, that where the wrong has been done by a weaker nation, the stronger one has generally been able to enforce redress; but where by a stronger nation, redress by war has been neither obtained nor expected by the weaker. On the contrary, the loss has been increased by the expenses of the war in blood and treasure. Yet it may have obtained another object equally securing itself from future wrong. It may have retaliated on the aggressor losses of blood and treasure far beyond the value to him of the wrong he had committed, and thus have made the advantage of that too dear a purchase to leave him in a disposition to renew the wrong in future. In this way the loss by the war may have secured the weaker nation from loss by future wrong.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American political philosopher, polymath, statesman, US President (1801-09)

Letter (1816-01-29) to Noah Worcester

(Source)

People in general will much better bear being told of their vices or crimes than of their little failings or weaknesses.

Lord Chesterfield (1694-1773) English statesman, wit [Philip Dormer Stanhope]

Letter to his son, #204 (26 Nov 1749)

(Source)

What one has, one ought to use; and whatever he does he should do with all his might.

[Quod est, eo decet uti: et quicquid agas, agere pro viribus.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Senectute [Cato Maior; On Old Age], ch. 9 / sec. 27 (9.27) (44 BC) [ed. Hoyt (1882)]

(Source)

On failing strength in old age.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:A man ought wele for to use in every age of that thyng that nature giveth hym, and also it apperteyneth that thou doo alle thyngs aftir the mesure and aftir the quantyte of thyne owne propre strength and not to usurpe and take the unto gretter thyngs than thou maist not nor hast no power to execute.

[tr. Worcester/Worcester/Scrope (1481)]For whatsoever is engraffed naturally in man, that is it fit and decent to use; and in all things that he taketh in hand to labour, and to do his diligent endeavour according to his strength.

[tr. Newton (1569)]For that which is naturally ingraffed in a man, that it becommeth him to use, and to desire to do nothing above his strength.

[tr. Austin (1648)]Then with that force content, which Nature gave,

Nor am I now displeas'd with what I have.

[tr. Denham (1669)]What strength and vigour, we have still remaining, ought to be preserv'd, by making the best use of them while we are able.

[tr. Hemming (1716)]What a Man has, he ought to use; and whatever he does, to do it according to his Power.

[tr. J. D. (1744)]For it is our business only to make the best use we can of the powers granted us by nature, and whatever we take in hand, to do it with all our might.

[tr. Logan (1750)]It is sufficient if we exert with spirit, upon every proper occasion, that degree of strength which still remains with us.

[tr. Melmoth (1773)]What is, that it becomes you to employ; and whatever you do, to do it according to the measure of your powers.

[Cornish Bros. ed. (1847)]What one has, that one ought to use; and whatever you do, you should do it with all your strength.

[tr. Edmonds (1874)]It is becoming to make use of what one has, and whatever you do, to do in proportion to your strength.

[tr. Peabody (1884)]You should use what you have, and whatever you may chance to be doing, do it with all your might.

[tr. Shuckburgh (1900)]What nature gives to man, that let him use:

Still fit your work according to your strength.

[tr. Allison (1916)]Such strength as a man has he should use, and whatever he does should be done in proportion to his strength.

[tr. Falconer (1923)]Use what you have: that is the right way; do what’s to be done in proportion as you have the strength for it.

[tr. Copley (1967)]Whatever strength you have at any given moment, you should use; and whatever you do, you should do it within the limitations of that strength.

[tr. Cobbold (2012)]You use what you have and gauge your activities accordingly.

[tr. Gerberding (2014)]You see, It’s a lot better to proceed

With your own strength and anything you do

According to your strength you should pursue.

[tr. Bozzi (2015)]

There are but two ways of rising in the world: either by your own industry or by the folly of others.

[Il n’y a au monde que deux manières de s’élever, ou par sa propre industrie, ou par l’imbécillité des autres.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 6 “Of Gifts of Fortune [Des Biens de Fortune],” § 52 (6.52) (1688) [tr. Van Laun (1885)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:There is but two ways of rising in the World, by your own Industry, and another's Weakness.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]There are only two ways of rising in the World, by your own Industry, or by the Weakness of others.

[Curll ed. (1713)]There are but two ways of rising in the World, by your own Industry, or the Weakness of others.

[Browne ed. (1752)]There are only two ways of getting on in the world: either by one's own cunning efforts, or by other people's foolishness.

[tr. Stewart (1970)]

There is no method more likely to cure passion and rashness, than the frequent and attentive consideration of one’s own weaknesses: this will work into the mind an habitual sense of the need one has of being pardoned, and will bring down the swelling pride and obstinacy of heart, which are the cause of hasty passion.

James Burgh (1714-1775) British politician and writer

The Dignity of Human Nature, Sec. 5 “Miscellaneous Thoughts on Prudence in Conversation” (1754)

(Source)

Let us speak, though we show all our faults and weaknesses — for it is a sign of strength to be weak, to know it, and out with it — not in a set way and ostentatiously, but incidentally and without premeditation.

No people in history have preserved their freedom who thought that by not being strong enough to protect themselves they might prove inoffensive to their enemies.

Dean Acheson (1893-1971) American statesman

National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68), Sec. 7 “Present Risks” (14 Apr 1950) [with Paul Nitze]

(Source)

Usually paraphrased as "No people in history have ever survived who thought they could protect their freedom by making themselves inoffensive to their enemies."

No Man is the worse for knowing the worst of himself.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs (compiler), # 3601 (1732)

(Source)

Every man is not ambitious, or courteous, or passionate; but every man has pride enough in his composition to feel and resent the least slight and contempt. Remember, therefore, most carefully to conceal your contempt, however just, wherever you would not make an implacable enemy. Men are much more unwilling to have their weaknesses and their imperfections known, than their crimes; and if you hint to a man that you think him silly, ignorant, or even ill-bred, or awkward, he will hate you more and longer, than if you tell him plainly, that you think him a rogue.

Lord Chesterfield (1694-1773) English statesman, wit [Philip Dormer Stanhope]

Letter to his son, #161 (5 Sep 1748)

(Source)

If youth knew; if age could.

[O si jeunesse scavoit,

O si vieillesse pouvoit.]Henri Estienne (1528 or 1531-1598) French printer and classical scholar [a.k.a. Henricus Stephanus]

Les Prémices, ou Le I livre Des Proverbes epigrammatizez [The First Fruits, or the First Book of Epigrammatized Proverbs], ch. 4, ep. 4 (1594)

(Source)

Variants:

- If youth only knew; if only age could.

- If youth knew; if age could.

- If only youth knew; if only age could.

The central fact of American civilization — one so hard for others to understand — is that freedom and justice and the dignity of man are not just words to us. We believe in them. Under all the growth and the tumult and abundance, we believe. And so, as long as some among us are oppressed — and we are part of that oppression — it must blunt our faith and sap the strength of our high purpose.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) American politician, educator, US President (1963-69)

Speech (1965-08-06), Signing of the Voting Rights Act, Washington, D.C.

(Source)

A cookbook is only as good as its poorest recipe.

Julia Child (1912-2004) American chef and writer

Quoted in Frank Prial, “Light’s Still on Julia Child,” New York Times (1997-10-08)

(Source)

Apparently a phrase she used frequently, as she drew on numerous cookbooks as source material and reference for her own. Another use can be found in an interview with Mike Sager, "What I've Learned: Julia Child," Esquire (1 Jun 2000).

Often given (perhaps from other occurrences) as "A cookbook is only as good as its worst recipe." For example, her obituary by Regina Schrambling, "Julia Child, the French Chef for a Jell-O Nation, Dies at 91," New York Times (13 Aug 2004).

ABSTAINER, n. A weak person who yields to the temptation of denying himself a pleasure. A Total Abstainer is one who abstains from everything, but abstention, and especially from inactivity in the affairs of others.

HENRY: What stronger breastplate than a heart untainted?

Thrice is he armed that hath his quarrel just,

And he but naked, though locked up in steel,

Whose conscience with injustice is corrupted.

It is not possible to lay down an inflexible rule as to when compromise is right and when wrong; when it is a sign of the highest statesmanship to temporize, and when it is merely a proof of weakness. Now and then one can stand uncompromisingly for a naked principle and force people up to it. This is always the attractive course; but in certain great crises it may be a very wrong course. Compromise, in the proper sense, merely means agreement; in the proper sense opportunism should merely mean doing the best possible with actual conditions as they exist.

A compromise which results in a half-step toward evil is all wrong, just as the opportunist who saves himself for the moment by adopting a policy which is fraught with future disaster is all wrong; but no less wrong is the attitude of those who will not come to an agreement through which, or will not follow the course by which, it is alone possible to accomplish practical results for good.

We are more apt to persecute the unfortunates than the scoundrels; the scoundrels may retaliate.

Paul Eldridge (1888-1982) American educator, novelist, poet

Maxims for a Modern Man, #952 (1965)

(Source)

Rudeness is the weak man’s imitation of strength.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

The Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 241 (1955)

(Source)

It has often been said that power corrupts. But it is perhaps equally important to realize that weakness, too, corrupts. Power corrupts the few, while weakness corrupts the many. Hatred, malice, rudeness, intolerance, and suspicion are the faults of weakness. The resentment of the weak does not spring from any injustice done to them but from the sense of inadequacy and impotence. They hate not wickedness but weakness. When it is their power to do so, the weak destroy weakness wherever they see it.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Passionate State of Mind, Aphorism 41 (1955)

(Source)

Strive to be patient; bear with the faults and frailties of others, for you, too, have many faults which others have to bear. If you cannot mould yourself as you would wish, how can you expect other people to be entirely to your liking?

[Stude patiens esse in tolerando aliorum defectus, et qualescumque infirmitates, quia et tu multa habes, quæ ab aliis oportet tolerari. Si non potes te talem facere qualem vis, quomodo poteris alium habere ad beneplacitum tuum?]

Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380-1471) German-Dutch priest, author

The Imitation of Christ [De Imitatione Christi], Book 1, ch. 16, v. 2 (1.16.2) (c. 1418-27) [tr. Sherley-Price (1952)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Study always that thou mayest be patient in suffering of other men’s defaults, for thou hast many things in thee that others do suffer of thee: and if thou canst not make thyself to be as thou wouldst, how mayest thou then look to have another to be ordered in all things after thy will?

[tr. Whitford/Raynal (1530/1871)]Study always to be patient in bearing other men's defects, for you have many in yourself that others suffer from you, and if you cannot make yourself be as you would, how may you then look to have another regulated in all things to suit your will?

[tr. Whitford/Gardiner (1530/1955)]Endeavour thy selfe patiently to bear with any faults and infirmities of others, for that thou thy selfe hast many things that must be borne withall by others. If thou canst not make thy selfe such a one as thou wouldst be, how canst thou expect to have another to thy liking in all things?

[tr. Page (1639), 1.16.6-7]Remember, that You also have many Failings of your own, by which the Patience of other People will have its turn of being exercised. And if you do (as certainly you cannot but) see this, think how unreasonable it is, to expect you should make others in all particulars, what you would have them to be; when you cannot so much as make your self, what you are sensible you ought to be.

[tr. Stanhope (1696; 1706 ed.)]Endeavor, to be always patient of the faults and imperfections of others; for thou haft many faults and imperfections of thy own, that require a reciprocation of forbearance. If thou art not able to make thyself that which thou wishest to be, how canst thou expect to mould another in conformity to thy will?

[tr. Payne (1803), 1.16.3]Endeavour to be patient in bearing with the defects and infirmities of others, of what sort soever they be; for that thyself also hast many [failings] which must be borne with by others. If thou canst not make thyself such an one as thou wouldest, how canst thou expect to have another in all things to thy liking?

[ed. Parker (1841)]Endeavour to be always patient of the faults and imperfections of others, whatever they may be; for thou hast many faults and imperfection of thy own, that require forbearance from others. If thou art not able to make thyself that which thou wishest to be, how canst thou expect to mould another in conformity to thy will?

[tr. Dibdin (1851)]Endeavour to be patient in bearing with defects and infirmities in others, of what kind soever; because thou also hast many things which others must bear with. If thou canst not make thyself such as thou wouldst, how canst thou expect to have another according to thy liking?

[ed. Bagster (1860)]Endeavour to be patient in bearing with other men’s faults and infirmities whatsoever they be, for thou thyself also hast many things which have need to be borne with by others. If thou canst not make thine own self what thou desireth, how shalt thou be able to fashion another to thine own liking.

[tr. Benham (1874)]Endeavour to be patient in bearing with the defects and infirmities of others, of what sort soever they be; for that thyself also hast many failings which must be borne with by others. If thou canst not make thyself such an one as thou wouldst, how canst thou expect to have another in all things to thy liking?

[tr. Anon. (1901)]Try to bear patiently with the defects and infirmities of others, whatever they may be, because you also have many a fault which others must endure. If you cannot make yourself what you would wish to be, how can you bend others to your will?

[tr. Croft/Bolton (1940)]Try to be patient in bearing with others’ failings and all kinds of weaknesses, for you too have many which must be put up with by others. If you cannot mould yourself exactly as you would, how can you get another to be satisfying to you?

[tr. Daplyn (1952)]Yes, you do well to cultivate patience in putting up with the shortcomings, the various disabilities of other people; only think how much they have to put up with in you! When you make such a failure of organizing your own life, how can you expect everybody else to come up to your own standards?

[tr. Knox-Oakley (1959)]Try to be patient in bearing with the failings and weaknesses of other people, whatever they may be. You too have many faults, which others have to endure. If you cannot make yourself the kind of person you wish, how can you expect to have someone else to your liking?

[tr. Knott (1962)]Seek always to be tolerant of the shortcomings and failings of others. They also have much to tolerate in you. If you are unable to mould yourself as you wish, how can you expect others to conform to your liking?

[tr. Rooney (1979)]Take pains to be patient in bearing all the faults and weaknesses of others, for you too have many flaws that others must put up with. If you cannot make yourself as you would like to be, how can you expect to have another person entirely to your liking?

[tr. Creasy (1989)]

A decline in courage may be the most striking feature that an outside observer notices in the West today. The Western world has lost its civic courage, both as a whole and separately, in each country, in each government, in each political party, and, of course, in the United Nations. Such a decline in courage is particularly noticeable among the ruling and intellectual elites, causing an impression of a loss of courage by the entire society. There are many courageous individuals, but they have no determining influence on public life.