Phryne had never liked pain. It hurt.

Kerry Greenwood (b. 1954) Australian author and lawyer

Phryne Fisher No. 10, Death Before Wicket, ch. 7 (2003)

(Source)

Quotations about:

pain

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

What would we think of a father, who should give a farm to his children, and before giving them possession should plant upon it thousands of deadly shrubs and vines; should stock it with ferocious beasts, and poisonous reptiles; should take pains to put a few swamps in the neighborhood to breed malaria; should so arrange matters, that the ground would occasionally open and swallow a few of his darlings, and besides all this, should establish a few volcanoes in the immediate vicinity, that might at any moment overwhelm his children with rivers of fire? Suppose that this father neglected to tell his children which of the plants were deadly; that the reptiles were poisonous; failed to say anything about the earthquakes, and kept the volcano business a profound secret; would we pronounce him angel or fiend?

And yet this is exactly what the orthodox God has done.

MEDEA: Men say we live a safe life in the home,

While they do battle with the spear.

But they are wrong; I’d rather stand three times

with shield in hand than give birth once.[ΜΉΔΕΙΑ: λέγουσι δ᾽ ἡμᾶς ὡς ἀκίνδυνον βίον

ζῶμεν κατ᾽ οἴκους, οἱ δὲ μάρνανται δορί,

κακῶς φρονοῦντες: ὡς τρὶς ἂν παρ᾽ ἀσπίδα

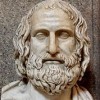

στῆναι θέλοιμ᾽ ἂν μᾶλλον ἢ τεκεῖν ἅπαξ.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Medea [Μήδεια], l. 248ff (431 BC) [tr. Ewans (2022)]

(Source)

This passage was often used by woman suffragists.

(Source (Greek)). Other translations:They still contend

That we, at home remaining, lead a life

Exempt from danger, while they launch the spear:

False are these judgements; rather would I thrice,

Arm'd with a target, in th' embattled field

Maintain my stand, than suffer once the throes

Of childbirth.

[tr. Wodhull (1782)]Yet will they say

We live an easy life, at home, secure

From danger, whilst they lift the spear in war:

Misjudging men; thrice would I stand in arms

On the rough edge of battle, e'er once bear

The pangs of childbirth.

[tr. Potter (1814)]But, say they, we, while they fight with the spear,

Lead in our homes a life undangerous:

Judging amiss; for I would liefer thrice

Bear brunt of arms than once bring forth a child.

[tr. Webster (1868)]And yet they say we live secure at home, while they are at the wars, with their sorry reasoning, for I would gladly take my stand in battle array three times o'er, than once give birth.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]But they say of us that we live a life of ease at home, but they are fighting with the spear; judging ill, since I would rather thrice stand in arms, than once suffer the pangs of child-birth.

[tr. Buckley (1892)]But we, say they, live an unperilled life

At home, while they do battle with the spear.

Falsely they deem: twice would I under shield

Stand, rather than bear childbirth peril once.

[tr. Way (Loeb) (1894)]And then, forsooth, 'tis they that face the call

Of war, while we sit sheltered, hid from all

Peril! -- False mocking! Sooner would I stand

Three times to face their battles, shield in hand,

Than bear one child.

[tr. Murray (1906)]But we, they say, live a safe life at home,

While they, the men, go forth in arms to war.

Fools! Three times would I rather take my stand

With sword and shield than bring to birth one child.

[tr. Murray (1906), per Yeroulanos]They tell us we live a sheltered life at home while they go to the wars; but that is nonsense. For I would rather go into battle twice than bear a child once.

[Source (1927)]What they say of us is that we have a peaceful time

Living at home, while they do the fighting in war.

How wrong they are! I would very much rather stand

Three times in the front of battle than bear one child.

[tr. Warner (1944)]Men boast their battles: I tell you this, and we know it:

It is easier to stand in battle three times, in the front line, in the stabbing fury, than to bear one child.

[tr. Jeffers (1946)]And, they tell us, we at home

Live free from danger, they go out to battle: fools!

I'd rather stand three times in the front line than bear

One child.

[tr. Vellacott (1963)]They say that we spend all our time at home,

And live safe lives, while they go out to battle.

What fools they are! I'd rather stand three times

Behind a shield, than bear a child once!

[tr. Podlecki (1989)]Men say that we live a life free from danger at home while they fight with the spear. How wrong they are! I would rather stand three times with a shield in battle than give birth once.

[tr. Kovacs (1994)]They say we live sheltered lives in the home, free from danger, while they wield their spears in battle -- what fools they are! I would rather face the enemy three times over than bear a child once.

[tr. Davie (1996)]Then people also say that while we live quietly and without any danger at home, the men go off to war. Wrong! One birth alone is worse than three times in the battlefield behind a shield.

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]They say that we live a life free of danger

at home while they face battle with the spear.

How wrong they are. I would rather stand three times

in the line of battle than once bear a child.

[tr. Luschnig (2007)][...] I would rather stand behind a shield three times than give birth once.

[tr. @sentantiq (2011)]They say that we live a peaceful life at home, while they do battle at spear point, but they reckon wrongly: I would rather stand armed with a shield thrice than give birth once.

[tr. @sentantiq [Erik] (2015)]They say we live secure in our households [oikoi], while they are off at war -- how worthlessly [kakōs] they think! How gladly would I three times over take my stand behind a shield rather than once give birth!

[tr. Coleridge / Ceragioli / Nagy / Hour25]

Besides, if a man is afraid of pain, he is afraid of something happening which will be part of the appointed order of things, and this is itself a sin; if he is bent on the pursuit of pleasure, he will not stop at acts of injustice, which again is manifestly sinful. No; when Nature herself makes no distinction — and if she did, she would not have brought pains and pleasures into existence side by side — it behooves those who would follow in her footsteps to be like-minded and exhibit the same indifference.

[ἔτι δὲ ὁ φοβούμενος τοὺς πόνους φοβηθήσεταί ποτε καὶ τῶν ἐσομένων τι ἐν τῷ κόσμῳ, τοῦτο δὲ ἤδη ἀσεβές: ὅ τε διώκων τὰς ἡδονὰς οὐκ ἀφέξεται τοῦ ἀδικεῖν, τοῦτο δὲ ἐναργῶς ἀσεβές: χρὴ δὲ πρὸς ἃ ἡ κοινὴ φύσις ἐπίσης ἔχει ῾οὐ γὰρ ἀμφότερα ἃν ἐποίει, εἰ μὴ πρὸς ἀμφότερα ἐπίσης εἶχἐ, πρὸς ταῦτα καὶ τοὺς τῇ φύσει βουλομένους ἕπεσθαι, ὁμογνώμονας ὄντας, ἐπίσης διακεῖσθαι.]

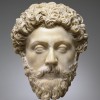

Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180) Roman emperor (161-180), Stoic philosopher

Meditations [To Himself; Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν], Book 9, ch. 1 (9.1) (AD 161-180) [tr. Staniforth (1964)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:Again, he that feareth pains and crosses in this world, feareth some of those things which some time or other must needs happen in the world. And that we have already showed to be impious. And he that pursueth after pleasures, will not spare, to compass his desires, to do that which is unjust, and that is manifestly impious. Now those things which unto nature are equally indifferent (for she had not created both, both pain and pleasure, if both had not been unto her equally indifferent): they that will live according to nature, must in those things (as being of the same mind and disposition that she is) be as equally indifferent.

[tr. Casaubon (1634)]To go on: He that's afraid of Pain, or Affliction; will be afraid of something that will always be in the World; but to be thus uneasie at the Appointments of Providence, is a failure in Reverence, and Respect. On the other hand; He that's violent in the pursuit of Pleasure, won't stick to turn Villain for the Purchase: And is not this plainly , an Ungracious, and an Ungodly Humour? To set the Matter Right, where the Allowance of God is equally clear; as it is with Regard to Prosperity, and Adversity: For had he not approved both these Conditions, He would never have made them: I say where the Good Liking of Heaven is equally clear, Ours ought to be so too: Because we ought to follow the Guidance of Nature, and the Sense of the Deity.

[tr. Collier (1701)]Besides, he who dreads pain, must sometimes dread that which must be a part of the order and beauty of the universe: this, now, is impious: and, then, he who pursues pleasures will not abstain from injury; and that is manifestly impious. But, in those things to which the common nature is indifferent, (for she had not made both, were she not indifferent to either); he who would follow nature, ought, in this too, to agree with her in his sentiments, and be indifferently dispos'd to either.

[tr. Hutcheson/Moor (1742)]Nay, he that is uneasy under affliction, is uneasy at what must necessarily exist in the world. This uneasiness, then, is a degree of impiety: and he who is too eager in his pursuit of pleasures, will not abstain from injustice to procure them. This is manifestly impious.

In short, as nature herself seems to view with indifference prosperity and adversity, (as she certainly does, or she would not produce them) so he who would follow nature as his guide, ought to do the same.

[tr. Graves (1792)]And further, he who is afraid of pain will sometimes also be afraid of some of the things which will happen in the world, and even this is impiety. And he who pursues pleasure will not abstain from injustice, and this is plainly impiety. Now with respect to the things towards which the universal nature is equally affected -- for it would not have made both, unless it was equally affected towards both -- towards these they who wish to follow nature should be of the same mind with it, and equally affected.

[tr. Long (1862)]Now, he that is afraid of pain will be afraid of something that will always be in the world; but this is a failure in reverence and respect. On the other hand, he that is violent in the pursuit of pleasure, will not hesitate to turn villain for the purchase. And is not this plainly an ungodly act? to set the matter right, where the allowance of God is equally clear, as it is with regard to prosperity and adversity (for had He not approved both of these conditions, He would never have made them both), I say, where the good liking of heaven is equally clear, ours ought to be so too, because we ought to follow the guidance of nature and the sense of the Deity.

[tr. Collier/Zimmern (1887)]Moreover, he who fears pain will some time fear that which will form part of the world-order; and therein he sins. And he who seeks after pleasures will not abstain from unjust doing; which is palpably an act of sin. Where Nature makes no difference -- and were she not indifferent, she would not bring both to pass -- those who would fain walk with Nature should conform their wills to like indifference.

[tr. Rendall (1898)]Again, he who dreads pain must sometimes dread a thing which will make part of the world order, and this is impious. And he who pursues pleasure will not abstain from injustice, and this is clear impiety. In those things to which the common nature is indifferent (for she had not made both, were she not indifferent to either), he who would follow Nature ought, in this also, to be of like mind with her, and shew the like indifference.

[tr. Hutcheson/Chrystal (1902)]Moreover he that dreads pain will some day be in dread of something that must be in the world. And there we have impiety at once. And he that hunts after pleasures will not hold his hand from injustice. And this is palpable impiety.

But those, who are of one mind with Nature and would walk in her ways, must hold a neutral attitude towards those things towards which the Universal Nature is neutral—for she would not be the Maker of both were she not neutral towards both.

[tr. Haines (Loeb) (1916)]He who fears pains will sometimes fear what is to come to pass in the Universe, and this is at once sinful, while he who pursues pleasures will not abstain from doing injustice, and this is plainly sinful. But those who wish to follow Nature, being like-minded with her, must be indifferent towards the things to which she is indifferent, for she would not create both were she not indifferent towards both.

[tr. Farquharson (1944)]And furthermore, one who is afraid of pain is sure to be afraid at times of things which come to pass in the universe, and that is already an impiety; and one that pursues pleasure will not abstain from injustice, and that is manifest impiety. But towards those things with regard to which universal nature is neutral (for she would not have created both opposites unless she was neutral with regard to both), it is necessary that those who wish to follow nature and be of one mind with her should also adopt a neutral attitude.

[tr. Hard (1997 ed.)]And moreover, to fear pain is to fear something that’s bound to happen, the world being what it is -- and that again is blasphemy. While if you pursue pleasure, you can hardly avoid wrongdoing -- which is manifestly blasphemous.

Some things nature is indifferent to; if it privileged one over the other it would hardly have created both. And if we want to follow nature, to be of one mind with it, we need to share its indifference.

[tr. Hays (2003)]Further, anyone who fears pain will also at times be afraid of some future event in the world, and that is immediate sin. And a man who pursues pleasure will not hold back from injustice -- an obvious sin. Those who wish to follow Nature and share her mind must themselves be indifferent to those pairs of opposites to which universal Nature is indifferent -- she would not create these opposites if she were not indifferent either way.

[tr. Hammond (2006)]And furthermore, one who is afraid of pain is sure to be afraid at times of things which come about in the universe, and that is already an impiety; and one who pursues pleasure will not abstain from injustice, and that is a manifest impiety. But towards those things with regard to which universal nature is neutral (for she would not have created both opposites unless she was neutral with regard to both), it is necessary that those who wish to follow nature and be of one mind with her should also adopt a neutral attitude.

[tr. Hard (2011 ed.)]

And to pursue pleasure as good, and flee from pain as evil — that too is blasphemous. Someone who does that is bound to find himself constantly reproaching nature — complaining that it doesn’t treat the good and bad as they deserve, but often lets the bad enjoy pleasure and the things that produce it, and makes the good suffer pain, and the things that produce pain.

[καὶ μὴν ὁ τὰς ἡδονὰς ὡς ἀγαθὰ διώκων, τοὺς δὲ πόνους ὡς κακὰ φεύγων ἀσεβεῖ: ἀνάγκη γὰρ τὸν τοιοῦτον μέμφεσθαι πολλάκις τῇ κοινῇ φύσει ὡς παῤ ἀξίαν τι ἀπονεμούσῃ τοῖς φαύλοις καὶ τοῖς σπουδαίοις, διὰ τὸ πολλάκις τοὺς μὲν φαύλους ἐν ἡδοναῖς εἶναι καὶ τὰ ποιητικὰ τούτων κτᾶσθαι, τοὺς δὲ σπουδαίους πόνῳ καὶ τοῖς ποιητικοῖς τούτου περιπίπτειν.]

Marcus Aurelius (AD 121-180) Roman emperor (161-180), Stoic philosopher

Meditations [To Himself; Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν], Book 9, ch. 1 (9.1) (AD 161-180) [tr. Hays (2003)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:He also that pursues after pleasures, as that which is truly good and flies from pains, as that which is truly evil: is impious. For such a one must of necessity oftentimes accuse that common nature, as distributing many things both unto the evil, and unto the good, not according to the deserts of either: as unto the bad oftentimes pleasures, and the causes of pleasures; so unto the good, pains, and the occasions of pains.

[tr. Casaubon (1634)]Farther: He that reckons Prosperity and Pleasure among Things really Good; Pain and Hardship amongst Things really Evil , can be no Pious Person: For such a Man will be sure to complain of the Administrations of Providence, Charge it with Mismatching Fortune, and Merit, and misapplying Rewards and Punishments: He'll often see Ill People furnish'd with Materials for Pleasure, and Regaled with the Relish of it : And good Men harrass'd and deprest, and meeting with nothing but Misfortune.

[tr. Collier (1701)]He, too, who pursues pleasure as good, and shuns pain as evil, is guilty of impiety: for such a one must needs frequently blame the common nature, as making some unworthy distributions to the bad and the good; because the bad oftimes enjoy pleasures, and possess the means of them; and the good often meet with pain, and what causes pain.

[tr. Hutcheson/Moor (1742)]Moreover, he who pursues pleasure, as if it were really good, or flies from pain, as if it were evil, he also is guilty of impiety. For he that is thus disposed, must necessarily complain often of the dispensations of Providence, as distributing its favours to the wicked and to the virtuous, without regard to their respective deserts; the wicked frequently abounding in pleasures, and in the means of procuring them, and the virtuous, on the contrary, being harassed with pain, and other afflictive circumstances.

[tr. Graves (1792)]And indeed he who pursues pleasure as good, and avoids pain as evil, is guilty of impiety. For of necessity such a man must often find fault with the universal nature, alleging that it assigns things to the bad and the good contrary to their deserts, because frequently the bad are in the enjoyment of pleasure and possess the things which procure pleasure, but the good have pain for their share and the things which cause pain.

[tr. Long (1862)]Further, he that reckons prosperity and pleasure among things really good, pain and hardship amongst things really evil, can be no pious person; for such a man will be sure to complain of the administrations of Providence, and charge it with mismatching fortune and merit. He will often see evil people furnished with materials for pleasure and regaled with the relish of it, and good men harassed and depressed, and meeting with nothing but misfortune.

[tr. Collier/Zimmern (1887)]Again, to seek pleasures as good, or to shun pains as evil, is to sin. For it inevitably leads to complaining against Nature for unfair awards to the virtuous and to the vile, seeing that the vile are oftentimes in pleasure and come by things pleasurable, while the virtuous are overtaken by pain and things painful.

[tr. Rendall (1898)]He, too, who pursues pleasure as good, and shuns pain as evil, is guilty of impiety. Such a one must needs frequently blame the common nature for unseemly awards of fortune to bad and to good men. For the bad often enjoy pleasures and possess the means to attain them, and the good often meet with pain and with what causes pain.

[tr. Hutcheson/Chrystal (1902)]Again he acts impiously who seeks after pleasure as a good thing and eschews pain as an evil. For such a man must inevitably find frequent fault with the Universal Nature as unfair in its apportionments to the worthless and the worthy, since the worthless are often lapped in pleasures and possess the things that make for pleasure, while the worthy meet with pain and the things that make for pain.

[tr. Haines (Loeb) (1916)]Moreover, he who runs after pleasures as goods and away from pains as evils commits sin; for being such a man he must necessarily often blame Universal Nature for distributing to bad and good contrary to their desert, because the bad are often employed in pleasures and acquire what may produce these, while the good are involved in pain and in what may produce this.

[tr. Farquharson (1944)]Again, it is a sin to pursue pleasure as a good and to avoid pain as an evil. It is bound to result in complaints that Nature is unfair in her rewarding of vice and virtue; since it is the bad who are so often in enjoyment of pleasures and the means to obtain them, while pains and events that occasion pains descend upon the heads of the good.

[tr. Staniforth (1964)]Again, one who pursues pleasure as good and tries to avoid pain as an evil is acting irreverently; for it is inevitable that such a person must often find fault with universal nature for assigning something to good people or bad which is contrary to their deserts, because it is so often the case that the bad devote themselves to pleasure and secure the things that give rise to it whilstr the good encounter pain and what gives rise to that.

[tr. Hard (1997 ed.)]Moreover, the pursuit of pleasure as a good and the avoidance of pain as an evil constitutes sin. Someone like that must inevitably and frequently blame universal Nature for unfair distribution as between bad men and good, since bad men are often deep in pleasures and the possessions which make for pleasure, while the good often meet with pain and the circumstances which cause pain.

[tr. Hammond (2006)]Again, one who pursues pleasures as being good and tries to avoid pains as being bad is acting irreverently; for it is inevitable that such a person must often find fault with universal nature for assigning something to good people or bad that is contrary to their deserts, because it is so often the case that the bad devote themselves to pleasure and secure the things that give rise to it while the good encounter pain and what gives rise to that.

[tr. Hard (2011 ed.)]

Man is subject to innumerable pains and sorrows by the very condition of humanity, and yet, as if nature had not sown evils enough in life, we are continually adding grief to grief, and aggravating the common calamity by our cruel treatment of one another.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Essay (1711-09-13), The Spectator, No. 169

(Source)

Our doings are not so important as we naturally suppose; our successes and failures do not after all matter very much. Even great sorrows can be survived; troubles which seem as if they must put an end to happiness for life, fade with the lapse of time until it becomes almost impossible to remember their poignancy. But over and above these self-centered considerations is the fact that one’s ego is no very large part of the world. The man who can center his thoughts and hopes upon something transcending self can find a certain peace in the ordinary troubles of life which is impossible to the pure egoist.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

Conquest of Happiness, Part 1, ch. 5 “Fatigue” (1930)

(Source)

CORPORAL: [trying to copy Lawrence’s snuffing a match with his fingers] Ow! It damn well ‘urts!

LAWRENCE: Certainly it hurts.

CORPORAL: Well what’s the trick then?

LAWRENCE: The trick, William Potter, is not minding if it hurts.

Robert Bolt (1924-1995) English dramatist

Lawrence of Arabia, Part 1, sc. 18 (1962) [with Michael Wilson]

(Source)

(Source (Video)). In the actual film, the last line is given, "not minding that it hurts."

To bear other Peoples afflictions, every one has Courage enough, and to spare.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1740 ed.)

(Source)

There seems to be a lot more interest in bypassing perishability than in engaging it, to the point that Christians who confess to being in a lot of pain can be accused of not having enough faith. Just yesterday I passed a church sign that read, “Do not fear; trust Jesus.” That is wonderful advice, but it leaves a lot of questions unanswered. Trust Jesus to do what? What is it that you are afraid of? Can you put it into words? If you can, then what is it that you trust Jesus to give you, or take away from you, to relieve you of your fear? Is that reasonable, based on what you know of his life story? What might your fear have to teach you, if you gave it a chance? Are you willing to do your part? Maybe I’m just cranky, but I don’t know many Christians who are interested in answering those kinds of questions.

Barbara Brown Taylor (b. 1951) American minister, academic, author

Interview (2013-12-19), “Material Faith,” by Meghan Larissa Good, The Other Journal, No. 23

(Source)

“He is mad as a hare, poor fellow,

And should be in chains” you say,

I haven’t a doubt of your statement,

But who isn’t mad, I pray?

Why, the world is a great asylum,

And the people are all insane,

Gone daft with pleasure or folly,

Or crazed with passion and pain.Ella Wheeler Wilcox (1850-1919) American author, poet, temperance advocate, spiritualist

Poem (1882), “All Mad,” st. 1, Maurine and Other Poems (1882 ed.)

(Source)

Also collected in Poems of Cheer (1910) and Poems of Life (1919).

No gains without pains.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1745 ed.)

(Source)

Franklin recapped this in his final Poor Richard Improved (1758 ed.): "There are no Gains, without Pains." This was in turn reprinted in abridged Way to Wealth (1773).

Sometimes erroneously cited to Poor Richard (1734 ed.); that has something different in structure and meaning: "Hope of gain / Lessens pain."

See also Breton (1577) and Herrick (1648).

SUSAN: The world is hard, they must take pain that look for any gayn.

Nicholas Breton (c. 1545/53 - c. 1625/26) English Renaissance poet and prose writer [Britton; Brittaine]

Workes of a Young Wyt (1577)

(Source)

First record of something resembling "No pain, no gain" in English.

Philosophy iz a fust rate thing to hav, but yu kant alleviate the gout with it, unless the gout happens to be on sum other phellow.

[Philosophy is a first rate thing to have, but you can’t alleviate the gout with it, unless the gout happens to be on some other fellow.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Josh Billings’ Trump Kards, ch. 2 “Grand Pa” (1874)

(Source)

ADRIANA: A wretched soul bruised with adversity

We bid be quiet when we hear it cry,

But were we burdened with like weight of pain,

As much or more we should ourselves complain.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Comedy of Errors, Act 2, sc. 1, l. 34ff (2.1.34-37) (1594)

(Source)

“How wonderful to be alive,” he thought. “But why does it always hurt?”

Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) Russian poet, novelist, and literary translator

Doctor Zhivago [До́ктор Жива́го], Part 1, ch. 1 “The Five O’Clock Express,” sec. 4 [Nika] (1955) [tr. Hayward & Harari (1958), US ed.]

(Source)

Alternate translations:"How wonderful to be alive," he thought. "But why does it always have to be so painful?"

[tr. Hayward & Harari (1958), UK ed.]"How good it is in this world!" he thought. "But why does it always come out so painful?"

[tr. Pevear & Volokhonsky (2010)]

Foolish people, I say, then, who have never experienced much of either, will tell you that mental distress is far more agonizing than bodily. Romantic and touching theory! so comforting to the love-sick young sprig who looks down patronizingly at some poor devil with a white starved face and thinks to himself, “Ah, how happy you are compared with me!” — so soothing to fat old gentlemen who cackle about the superiority of poverty over riches. But it is all nonsense — all cant. An aching head soon makes one forget an aching heart. A broken finger will drive away all recollections of an empty chair. And when a man feels really hungry he does not feel anything else.

Jerome K. Jerome (1859-1927) English writer, humorist [Jerome Klapka Jerome]

Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow, “On Eating and Drinking” (1886)

(Source)

To fight a real sorrow, a real loss, a real insult, a real disillusion, a real treachery was infinitely less difficult than to spend a night without sleep struggling with ghosts. The imagination is far better at inventing tortures than life because the imagination is a demon within us and it knows where to strike, where it hurts.

There is a legend about a bird that sings just once in its life, more sweetly than any other creature on the face of the earth. From the moment it leaves the nest it searches for a thorn tree and does not rest until it has found one. Then, singing among the savage branches, it impales itself upon the longest, sharpest spine. Dying, it rises above its own agony to out-carol the lark and the nightingale. One superlative song, existence the price. But the whole world stills to listen, and God in His heaven smiles. For the best is only bought at the cost of the great pain. … Or so says the legend.

You have to laugh at the things that hurt you just to keep yourself in balance, just to keep the world from running you plumb crazy.

Ken Kesey (1935-2001) American novelist, essayist, countercultural figure

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Part 3 (1962)

(Source)

A goodly fellow by his looks, though worn

As most good fellows are, by pain or pleasure,

Which tear life out of us before our time;

I scarce know which most quickly: but he seems

To have seen better days, as who has not

Who has seen yesterday?

Tastes differ, but I know of no finer prayer than the one which ends old Indian dramas (just as in former times English plays ended with a prayer for the King). It runs: “May all living beings remain free from pain.”

[Der Geschmack ist verschieden; aber ich weiß mir kein schöneres Gebet, als Das, womit die Alt-Indischen Schauspiele (wie in früheren Zeiten die Englischen mit dem für den König) schließen. Es lautet: „Mögen alle lebenden Wesen von Schmerzen frei bleiben.”]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

On the Basis of Morality [Über die Grundlage der Moral], § 19.4 (Part 3, ch. 8.4) (1840) [tr. Saunders (1965)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:In former times the English plays used to finish with a petition for the King. The old Indian dramas close with these words: "May all living beings be delivered from pain." Tastes differ; but in my opinion there is no more beautiful prayer than this.

[tr. Bullock (1903)]

He’s the one who gives us wine to ease our pain.

If you take wine away, love will die, and

every other source of human joy will follow.[τὴν παυσίλυπον ἄμπελον δοῦναι βροτοῖς.

οἴνου δὲ μηκέτ᾽ ὄντος οὐκ ἔστιν Κύπρις

οὐδ᾽ ἄλλο τερπνὸν οὐδὲν ἀνθρώποις ἔτι.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bacchæ [Βάκχαι], l. 772ff [First Messenger/Ἄγγελος] (405 BC) [tr. Woodruff (1999)]

(Source)

Speaking of Dionysus. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:He, the grape, that med'cine for our cares,

Bestow'd on favour'd mortals. Take away

The sparkling Wine, fair Venus smiles no more

And every pleasure quits the human race.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]He gives to mortals the vine that puts an end to grief. Without wine there is no longer Aphrodite or any other pleasant thing for men.

[tr. Buckley (1850)]He hath given the sorrow-soothing vine to man

For where wine is not love will never be,

Nor any other joy of human life.

[tr. Milman (1865)]He gives the soothing vine

Which stills the sorrow of the human heart;

Where wine is absent, love can never be;

Where wine is absent, other joys are gone.

[tr. Rogers (1872), l. 732ff]’Twas he that gave the vine to man, sorrow’s antidote. Take wine away and Cypris flies, and every other human joy is dead.

[tr. Coleridge (1891)]He gave men the grief-assuaging vine.

When wine is no more found, then Love is not,

Nor any joy beside is left to men.

[tr. Way (1898)]This is he who first to man did give

The grief-assuaging vine. Oh, let him live;

For if he die, then Love herself is slain,

And nothing joyous in the world again!

[tr. Murray (1902)]It was he,

or so they say, who gave to mortal men

the gift of lovely wine by which our suffering

is stopped. And if there is no god of wine,

there is no love, no Aphrodite either,

nor other pleasures left to men.

[tr. Arrowsmith (1960)]They say that he

has given to men the vine that ends pain.

If wine were no more, then Cypris is no more

nor anything else delighted for mankind.

[tr. Kirk (1970)]It was he who gave men the gift of the vine as a cure for sorrow. And if there were no more wine, why, there's an end of love, and of every other pleasure in life.

[tr. Vellacott (1973)]Didn't he make us

Mortal men the gift of wine? If that is true

You have much to thank him for -- wine makes

Our labors bearable. Take wine away

And the world is without joy, tolerance, or love.

[tr. Soyinka (1973)]The sorrow-ceasing vine he gives to mortals.

Without wine there is no Aphrodite,

nor longer any other delight for men.

[tr. Neuburg (1988)]It was he,

so they say, who gave to us, poor mortals, the gift of wine,

that numbs all sorrows.

If wine should ever cease to be,

then so will love.

No pleasures left for men.

[tr. Cacoyannis (1982)]He himself, I hear them say,

Gave the pain-killing vine to men.

When wine is no more, neither is love.

Nor any other pleasure for mankind.

[tr. Blessington (1993)]He gave to mortals the vine that stops pain.

If there were no more wine, then there is no more Aphrodite

nor any other pleasure for mankind.

[tr. Esposito (1998)]It's he who gave

To mortals the vine that stops all suffering.

Adn if wine were to exist no longer, then

Neither would the goddess Aphrodite,

Nor anything of pleasure for us mortals.

[tr. Gibbons/Segal (2000), l. 885ff]He gave to mortals the vine that puts an end to pain. If there is no wine, there is no Aphrodite or any other pleasure for mortals.

[tr. Kovacs (2002)]Besides, he's given us the gift of wine,

Without which man desires nor endures not.

[tr. Teevan (2002)]He’s the god who brought the wine to the mortals. Great stuff that. It stops all sadness. Truth is, my Lord, when the wine is missing so does love and then… well, then there’s nothing sweet left for us mortals.

[tr. Theodoridis (2005)]He is the one who gave us the vine that gives

pause from pain; and if there is no wine, there'll be no more

Aphrodite, & there is no other gift to give such pleasure to us mortals.

[tr. Valerie (2005)]He gives to mortal human beings that vine which puts an end to human grief. Without wine, there's no more Aphrodite -- or any other pleasure left for men.

[tr. Johnston (2008)]He is great in so many ways -- not least, I hear say,

for his gift of wine to mortal men.

Wine, which puts an end to sorrow and to pain.

And if there is no wine, there is no Aphrodite,

And without her no pleasure left at all.

[tr. Robertson (2014)]When wine is gone, there is no more Cypris,

nor anything else to delight a mortal heart.

[tr. @sentantiq/Robinson (2015)]He gave mortals the pain-pausing vine.

When there is no wine, Cypris is absent,

And human beings have no other pleasure.

[tr. @sentantiq (2015)]I’ve heard he gave the grapevine to us mortals, as an end to pain.

And without wine, we’ve got no chance with Aphrodite. Or anything else good, for that matter.

[tr. Pauly (2019)]He even gives to mortals the grape that brings relief from cares. Without wine there is no longer Kypris or any other delightful thing for humans.

[tr. Buckley/Sens/Nagy (2020)]He gave mortals the pain-relieving vine.

But when there is no more wine, there is no Aphrodite

Nor any other pleasure left for human beings.

[tr. @sentantiq (2021)]

I tell you this, and I tell you plain:

What you have done, you will do again;

You will bite your tongue, careful or not,

Upon the already-bitten spot.Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 5 (1963)

(Source)

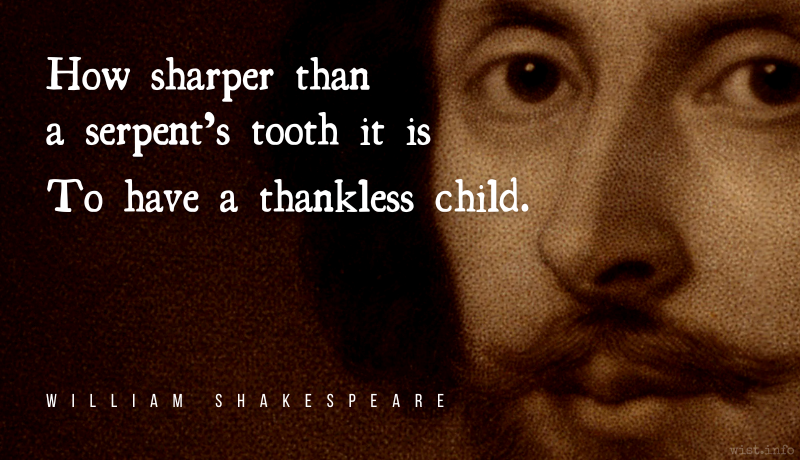

LEAR: How sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is

To have a thankless child.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

King Lear, Act 1, sc. 4, l. 302ff (1.4.302-303) (1606)

(Source)

MERL: Funny thing about change, it’s like pulling off a bandage. Hurts like hell when you do it, but you always feel better after.

Hart Bochner (b. 1956) Canadian actor, film director, screenwriter, producer

Just Add Water (2008)

(Source)

The role of Merl Striker was played by Danny Devito.

And the host laughed and wept, and in the midst of their merriment and tears the clear voice of the minstrel rose like silver and gold, and all men were hushed. And he sang to them, now in the Elven-tongue, now in the speech of the West, until their hearts, wounded with sweet words, overflowed, and their joy was like swords, and they passed in thought out to regions where pain and delight flow together and tears are the very wine of blessedness.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) English writer, fabulist, philologist, academic [John Ronald Reuel Tolkien]

The Lord of the Rings, Vol. 3: The Return of the King, Book 6, ch. 4 “The Field of Cormallen” (1955)

(Source)

Everywhere, wrenching grief, everywhere, terror

and a thousand shapes of death.[Crudelis ubique

Luctus, ubique pavor, et plurima mortis imago.]Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

The Aeneid [Ænē̆is], Book 2, l. 368ff (2.368-369) (29-19 BC) [tr. Fagles (2006), ll. 461-462]

(Source)

On the fighting in the streets of Troy. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:In all parts cruell grief, in all parts feare,

And various shapes of death was every where.

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]All parts resound with tumults, plaints, and fears;

And grisly Death in sundry shapes appears.

[tr. Dryden (1697)]Every where is cruel sorrow, every where terror and death in thousand shapes.

[tr. Davidson/Buckley (1854)]Dire agonies, wild terrors swarm,

And Death glares grim in many a form.

[tr. Conington (1866)]And everywhere are sounds of bitter grief,

And terror everywhere, and shapes of death.

[tr. Cranch (1872), l. 506-507]Everywhere is cruel agony, everywhere terror, and the sight of death at every turn.

[tr. Mackail (1885)]Grim grief on every side,

And fear on every side there is, and many-faced is death.

[tr. Morris (1900)]All around

Wailings, and wild affright and shapes of death abound.

[tr. Taylor (1907), st. 49, l. 440-41]Anguish and woe

were everywhere; pale terrors ranged abroad,

and multitudinous death met every eye.

[tr. Williams (1910)]Everywhere sorrow,

Everywhere panic, everywhere the image

Of death, made manifold.

[tr. Humphries (1951)]All over the town you saw

Heart-rending agony, panic, and every shape of death.

[tr. Day Lewis (1952)]And everywhere

are fear, harsh grief, and many shapes of slaughter.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1971), l. 497-98]Grief everywhere,

Everywhere terror, and all shapes of death.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1981)]Bitter grief was everywhere. Everywhere there was fear, and death in many forms.

[tr. West (1990)]Cruel mourning is everywhere,

everywhere there is panic, and many a form of death.

[tr. Kline (2002)]Raw fear

Was everywhere, grief was everywhere,

Everywhere the many masks of death.

[tr. Lombardo (2005)]All around were bitter grief and fear, and different scenes of death.

[tr. Bartsch (2021)]

It is easy when you’ve been hurt by love to give it up as a bad job and make independence your new god, taking the love you had to give and turning it in upon yourself. And most of us have had to protect ourselves so much at times that we’ve given up the high road and taken the low. But independence carried to the furthest extreme is just loneliness and death, nothing more than another defense, and there is no growth in it, only a safe harbor for a while. The answer doesn’t lie in learning how to protect ourselves from life — it lies in learning how to become strong enough to let a bit more of it in.

Merle Shain (1935-1989) Canadian journalist and author

When Lovers Are Friends, ch. 1 (1978)

(Source)

Does anything in nature despair except man? An animal with a foot caught in a trap does not seem to despair. It is too busy trying to survive. It is all closed in, to a kind of still, intense waiting. Is this a key? Keep busy with survival. Imitate the trees. Learn to lose in order to recover, and remember that nothing stays the same for long, not even pain, psychic pain. Sit it out. Let it all pass. Let it go.

May Sarton (1912-1995) Belgian-American poet, novelist, memoirist [pen name of Eleanore Marie Sarton]

Journal of a Solitude, “October 6th” (1973)

(Source)

Nothing could be less worthy of you than to think anything worse than dishonor, infamous behavior, and wickedness. To escape these, any pain is not so much as to be avoided as to be sought voluntarily, undergone, and welcomed.

[Quid enim minus est dignum quam tibi peius quicquam videri dedecore flagitio turpitudine? Quae ut effugias, quis est non modo recusandus, sed non ultro adpetendus subeundus excipiendus dolor?]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Tusculan Disputations [Tusculanae Disputationes], Book 2, ch. 5 (2.5) / sec. 14 [Marcus] (45 BC) [tr. Douglas (1990)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:For what is more unsuitable to that high Character, than for you to think any thing worse, than dishonour, scandal, baseness? to avoid which, what Pain would not only not be declin'd, but also be eagerly pursu'd, undergone, encounter'd?

[tr. Wase (1643)]For what is so unbecoming? What can appear worse to you, than disgrace, wickedness, immorality? To avoid which, what pain should we not only not refuse, but willingly take on ourselves?

[tr. Main (1824)]For what is less worthy than for anything to appear worse to you than disgrace, turpitude, wickedness? which to escape, what pain is to be refused, or rather not to be welcomed, sought for, embraced?

[tr. Otis (1839)]For what is so unbecoming -- what can appear worse to you, than disgrace, wickedness, immorality? To avoid which, what pain is there which we ought not (I will not say to avoid shirking, but even) of our own accord to encounter, and undergo, and even to court?

[tr. Yonge (1853)]For what is more unworthy than that anything should seem to you worse than disgrace, crime, baseness? To escape these what pain should be not only not shunned, but voluntarily sought, endured, welcomed?

[tr. Peabody (1886)]There is nothing more unworthy than for you to think anything worse than disgrace, criminal behavior, and infamous conduct. In order to escape these, any pain is not so to be rejected, as to be actively sought out, undergone, welcomed.

[tr. Davie (2017)]

I do not deny that pain is painful — otherwise, why would bravery be desired? But I do say that it is suppressed through patience, if we possess any amount at all. If we have none, then why do we raise philosophy on high and robe ourselves in its glory?

[Non ego dolorem dolorem esse nego — cur enim fortitudo desideraretur? — sed eum opprimi dico patientia, si modo est aliqua patientia: si nulla est, quid exornamus philosophiam aut quid eius nomine gloriosi sumus?]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Tusculan Disputations [Tusculanae Disputationes], Book 2, ch. 14 (2.14) / sec. 33 (45 BC) [tr. @sentantiq (2020)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:I do not deny Pain to be Pain, for what need else were there of Fortitude? but I say it may be suppress'd by Patience, if there be any such Virtue as Patience; if there be none, why do we magnifie Philosophy? or why do we value our selves in being denominated from her?

[tr. Wase (1643)]I do not deny pain to be pain, for were that the case, in what would courage consist? but I say it should be assuaged by patience, if there be such a thing as patience: if there be no such thing, then why do we speak so in praise of philosophy? or why do we glory in its name?

[tr. Main (1824)]That pain is pain, I do not deny; for why should fortitude be desired? but I say it is kept under by patience: -- if, at least, there be any patience. If there be no such thing, why do we extol philosophy? or why do we glory in her name?

[tr. Otis (1839)]I do not deny pain to be pain; for were that the case, in what would courage consist? but I say it should be assuaged by patience, if there be such a thing as patience: if there be no such thing, why do we speak so in praise of philosophy? or why do we glory in its name?

[tr. Yonge (1853)]I do not deny that pain is pain; else where were the need of fortitude? But I do say that pain is subdued by patience, if patience be a real quality; and if it be not, why do we lavish praises on philosophy? Or what is there to boast of in its name?

[tr. Peabody (1886)]I don't deny that pain is pain -- otherwise why should there be felt a need for courage? But I say that it is overcome by endurance if only there is such a thing as endurance: if there isn't, why do we sing the praises of philosophy, or why are we boastful on its behalf?

[tr. Douglas (1990)]

Old women will often bear the lack of food for two or three days. But take food from an athlete for a single day, he will implore the very Olympian Jupiter for whose honor he is in training, and will cry that he cannot bear it. Great is the power of habit.

[Aniculae saepe inediam biduum aut triduum ferunt; subduc cibum unum diem athletae: Iovem, Iovem Olympium, eum ipsum, cui se exercebit, implorabit, ferre non posse clamabit.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

Tusculan Disputations [Tusculanae Disputationes], Book 2, ch. 17 (2.17) / sec. 40 (45 BC) [tr. Peabody (1886)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alternate translations:Weak old Women oftentimes go without eating two or three days together; do but with-hold Meat one day from a Wrestler, he will cry out upon Olympian Jupiter; the same to whose Honor he shall exercise himself. He will cry he cannot bear it. Great is the Power of Custom.

[tr. Wase (1643)]You may often hear of diminutive old women living without victuals three or four days; but take away a wrestler's provision for but one day, he will implore Jupiter Olympus, the very god for whom he exercises himself: he will cry out, It is intolerable. Great is the force of custom!

[tr. Main (1824)]Tender old women often support a fast of two or three days. Withdraw his rations for one day from a wrestler; he will appeal to that Olympic Jove himself, for whom he exercises; he will cry out it impossible to bear it. Great is the force of habit.

[tr. Otis (1839)]You may often hear of old women living without victuals for three or four days: but take away a wrestler's provisions but for one day, and he will implore the aid of Jupiter Olympius, the very God for whom he exercises himself: he will cry out that he cannot endure it. Great is the force of custom!

[tr. Yonge (1853)]Feeble old women often endure hunger for two or three days. Take food away from an athlete for just one day. He will appeal to Jupiter, that Olympian Jupiter, the very one for whom he will be doing this training -- he will cry out that he can't bear it. Practice has great power.

[tr. Douglas (1990)]Little old ladies often bear a two or three day period of fasting; but take away an athlete’s food for a day, and he will beg for relief from Jove! Olympian Jove, the one for whom he exercises! And he’ll tell you that he simply cannot bear it.

[tr. @sentantiq (2015)]Old women regularly endure a lack of food for a period of three or four days; take from an athlete his food for a single day and he will appeal to olympian Jupiter, the very god in whose honor he trains, he will cry out that he can't bear it. The force of habit is considerable.

[tr. Davie (2017)]

Out of instinct for self-preservation, and logically enough, [the mind] asks, “If it is a good and holy thing to be punished, must it not also be a good and holy thing to punish?” It answers that it is; and our earth becomes the hell it is. Thus we human beings plant in ourselves the perennial blossom of cruelty — the conviction that if we hurt other people we are doing good to ourselves and to life in general.

Rebecca West (1892-1983) British author, journalist, literary critic, travel writer [pseud. for Cicily Isabel Fairfield]

“Pleasure Be Your Guide,” The Nation, “Living Philosophies” series #10 (25 Feb 1939)

(Source)

Adapted into Clifton Fadiman, I Believe: The Personal Philosophies of Certain Eminent Men and Women of Our Time (1952).

But indeed we need no further argument in favor of taking pleasure as a standard when we consider the only alternative that faces us. If we do not live for pleasure we shall soon find ourselves living for pain. If we do not regard as sacred our own joys and the joys of others, we open the door and let into life the ugliest attribute of the human race, which is cruelty.

Rebecca West (1892-1983) British author, journalist, literary critic, travel writer [pseud. for Cicily Isabel Fairfield]

“Pleasure Be Your Guide,” The Nation, “Living Philosophies” series #10 (25 Feb 1939)

(Source)

Adapted into Clifton Fadiman, I Believe: The Personal Philosophies of Certain Eminent Men and Women of Our Time (1952).

The belief that all higher life is governed by the idea of renunciation poisons our moral life by engendering vanity and egotism. But if we take gratification as our ideal we thereby impose on ourselves a program of self-restraint; for if we claim that we are under the necessity of learning all that we can about reality, and that we learn most through pleasure, we must also admit that we are under the necessity of hearing what our fellow-creatures learn about it and of working out a system by which we will curb our pleasures so that they do not interfere with those of others. If, however, we claim that it is by renunciation that we achieve wisdom, we have no logical reason for feeling any disapproval of conditions that thrust pain and deprivation on others.

Rebecca West (1892-1983) British author, journalist, literary critic, travel writer [pseud. for Cicily Isabel Fairfield]

“Pleasure Be Your Guide,” The Nation, “Living Philosophies” series #10 (25 Feb 1939)

(Source)

Adapted into Clifton Fadiman, I Believe: The Personal Philosophies of Certain Eminent Men and Women of Our Time (1952).

Is there any stab as deep as wondering where and how much you failed those you love?

Florida Scott-Maxwell (1883-1979) American-British playwright, author, psychologist

The Measure of My Days (1968)

(Source)

The pain others give passes away in their later kindness, but that of our own blunders, especially when they hurt our vanity, never passes away.

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) Irish poet and dramatist

Journal entry #105 (18 Mar 1909)

(Source)

See also "Vacillation."

On the other hand, we denounce with righteous indignation and dislike men who are so beguiled and demoralized by the charms of pleasure of the moment, so blinded by desire, that they cannot foresee the pain and trouble that are bound to ensue; and equal blame belongs to those who fail in their duty through weakness of will, which is the same as saying through shrinking from toil and pain. These cases are perfectly simple and easy to distinguish. In a free hour, when our power of choice is untrammeled and when nothing prevents our being able to do what we like best, every pleasure is to be welcomed and every pain avoided. But in certain circumstances and owing to the claims of duty or the obligations of business it will frequently occur that pleasures have to be repudiated and annoyances accepted. The wise man therefore always holds in these matters to this principle of selection: he rejects pleasures to secure other greater pleasures, or else he endures pains to avoid worse pains.

[At vero eos et accusamus et iusto odio dignissimos ducimus, qui blanditiis praesentium voluptatum deleniti atque corrupti, quos dolores et quas molestias excepturi sint, obcaecati cupiditate non provident, similique sunt in culpa, qui officia deserunt mollitia animi, id est laborum et dolorum fuga. et harum quidem rerum facilis est et expedita distinctio. nam libero tempore, cum soluta nobis est eligendi optio, cumque nihil impedit, quo minus id, quod maxime placeat, facere possimus, omnis voluptas assumenda est, omnis dolor repellendus. temporibus autem quibusdam et aut officiis debitis aut rerum necessitatibus saepe eveniet, ut et voluptates repudiandae sint et molestiae non recusandae. itaque earum rerum hic tenetur a sapiente delectus, ut aut reiciendis voluptatibus maiores alias consequatur aut perferendis doloribus asperiores repellat.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum [On the Ends of Good and Evil], Book 1, sec. 33 (ch. 10) (44 BC) [tr. Rackham (1914)]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- "Then again we criticize and consider wholly deserving of our odium those who are so seduced and corrupted by the blandishments of immediate pleasure that they fail to foresee in their blind passion the pain and harm to come. Equally blameworthy are those who abandon their duties through mental weakness -- that is, through the avoidance of effort and pain. It is quite simple and straightforward to distinguish such cases. In our free time, when our choice is unconstrained and there is nothing to prevent us doing what most pleases us, every pleasure is to be tasted, every pain shunned. But in certain circumstances it will often happen that either the call of duty or some sort of crisis dictates that pleasures are to be repudiated and inconveniences accepted. And so the wise person will uphold the following method of selecting pleasures and pains: pleasures are rejected when this results in other greater pleasures; pains are selected when this avoids worse pains." [On Moral Ends, tr. Woolf (2001)]

- "But in truth we do blame and deem most deserving of righteous hatred the men who, enervated and depraved by the fascination of momentary pleasures, do not foresee the pains and troubles which are sure to befall them, because they are blinded by desire, and in the same error are involved those who prove traitors to their duties through effeminacy of spirit, I mean because they shun exertions and trouble. Now it is easy and and simple to mark the difference between these cases. For at our seasons of ease, when we have untrammelled freedom of choice, and when nothing debars us from the power of following the course that pleases us best, then pleasure is wholly a matter for our selection and pain for our rejection. On certain occasions however either through the inevitable call of duty or through stress of circumstances, it will often come to pass that we must put pleasures from us and must make no protest against annoyance. So in such cases the principle of selection adopted by the wise man is that he should either by refusing cerftain pleasures attain to other and greater pleasures or by enduring pains should ward off pains still more severe." [tr. Reid (1883)]

- "But we do accuse those men, and think them entirely worthy of the greatest hatred, who, being made effeminate and corrupted by the allurements of present pleasure, are so blinded by passion that they do not foresee what pains and annoyances they will hereafter be subject to; and who are equally guilty with those who, through weakness of mind, that is to say, from eagerness to avoid labour and pain, desert their duty. And the distinction between these things is quick and easy. For at a time when we are free, when the option of choice is in our own power, and when there is nothing to prevent our being able to do whatsoever we choose, then every pleasure may be enjoyed, and every pain repelled. But on particular occasions it will often happen, owing whether to the obligations of duty or the necessities of business, that pleasures must be declined and annoyances must not be shirked. Therefore the wise man holds to this principle of choice in those matters, that he rejects some pleasures, so as, by the rejection to obtain others which are greater, and encounters some pains, so as by that means to escape others which are more formidable." [On the Chief Good and Evil, tr. Yongue (1853)]

The barbarous custom of having men beaten who are suspected of having important secrets to reveal must be abolished. It has always been recognized that this way of interrogating men, by putting them to torture, produces nothing worthwhile. The poor wretches say anything that comes into their mind and what they think the interrogator wishes to know.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) French emperor, military leader

Letter to Louis Alexandre Berthier (11 Nov 1798), in Correspondence Napoleon, Vol 5, #3605 [ed. Henri Plon (1861)]

(Source)

He imagined the pain of the world to be like some formless parasitic being seeking out the warmth of human souls wherein to incubate and he thought he knew what made one liable to its visitations. What he had not known was that it was mindless and so had no way to know the limits of those souls and what he feared was that there might be no limits.

Cormac McCarthy (1933-2023) American novelist, playwright, screenwriter

All the Pretty Horses (1992)

(Source)

The man who looks for security, even in the mind, is like a man who would chop off his limbs in order to have artificial ones which will give him no pain or trouble.

There are few of us who are not protected from the keenest pain by our inability to see what it is that we have done, what we are suffering, and what we truly are. Let us be grateful to the mirror for revealing to us our appearances only.

Samuel Butler (1835-1902) English novelist, satirist, scholar

Erewhon, ch. 3 “Up the River” (1872)

(Source)

We have all heard enough to fill a book about Dr. Johnson’s incivilities. I wish they would compile another book consisting of Dr. Johnson’s apologies. There is no better test of a man’s ultimate chivalry and integrity than how he behaves when he is wrong; and Johnson behaved very well. He understood (what so many faultlessly polite people do not understand) that a stiff apology is a second insult. He understood that the injured party does not want to be compensated because he has been wronged; he wants to be healed because he has been hurt.

Sorrow is how we learn to love. Your heart isn’t breaking. It hurts because it’s getting larger. The larger it gets, the more love it holds.

Sure, there are differences in degree, but we’ve got to stop comparing wounds and go out after the system that does the wounding.

There is not so much Comfort in the having of Children as there is Sorrow in parting with them.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs (compiler), # 4932 (1732)

(Source)

A stranger to human nature, who saw the indifference of men about the misery of their inferiors, and the regret and indignation which they feel for the misfortunes and sufferings of those above them, would be apt to imagine that pain must be more agonizing, and the convulsions of death more terrible, to people of higher rank than to those of meaner stations.

The more you are drawn to put yourself in the place of the other person, the more you feel the pain inflicted upon him, the insult offered him, the injustice of which he is a victim, the more you will be urged to act so that you may prevent the pain, insult, or injustice.

The most general survey shows us that the two foes of human happiness are pain and boredom.

[Der allgemeinste Überblick zeigt uns, als die beiden Feinde des menschlichen Glückes, den Schmerz und die Langeweile.]

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. 1, “Aphorisms on the Wisdom of Life [Aphorismen zur Lebensweisheit],” ch. 2 “Of What One Is” [Von dem, was einer ist]” (1851) [tr. Saunders (1890)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:The most general survey shows that pain and boredom are the two foes of human happiness.

[tr. Payne (1974)]

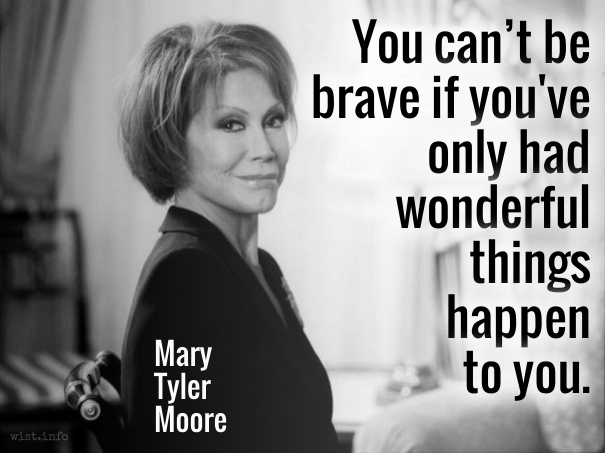

Pain nourishes my courage. You have to fail in order to practice being brave. You can’t be brave if you’ve only had wonderful things happen to you.

Mary Tyler Moore (1936-2017) American actress, producer, and social advocate

Interview, McCall’s, Vol. 108 (1980)

(Source)

The more you try to avoid suffering, the more you suffer, because smaller and more insignificant things begin to torture you, in proportion to your fear of being hurt. The one who does most to avoid suffering is, in the end, the one who suffers most.

Philosophy easily triumphs over past ills and ills to come, but present ills triumph over philosophy.

[La philosophie triomphe aisément des maux passés et des maux à venir; mais les maux présents triomphent d’elle.]

François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) French epigrammatist, memoirist, noble

Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales [Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims], ¶22 (1665-1678) [tr Tancock (1959)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). French variants:La philosophie triomphe aisément des maux passés et de ceux qu’un ne sont pas prêts d’arriver; mais les maux présents triomphent d'elle.

(1665)]La philosophie ne fait des merveilles que contre les maux passés ou contre ceux qui ne sont pas prêts d’arriver, mais elle n’a pas grande vertu contre les maux présents.

[Manuscript]

Alternate English translations:Philosophy may easily triumph over Evils past, as also over those not yet ready to assault a man; but the present triumph over it.

[tr. Davies (1669), ¶87]Philosophy finds it an easie matter to vanquish past and future Evils, but the present are commonly too hard for it.

[tr. Stanhope (1694), ¶23]Philosophy easily triumphs over past and future ills; but present ills triumph over philosophy.

[pub. Donaldson (1783), "Ills" ¶242]Philosophy easily triumphs over ills both past and future; but present ills triumph over philosophy.

[ed. Carville (1835), "Ills" ¶211]Philosophy easily triumphs over past and future ills: but religion only triumphs over the present ones.

[ed. Carville (1835), "Philosophers" ¶303]Philosophy triumphs easily over past, and over future evils, but present evils triumph over philosophy.

[ed. Gowens (1851), ¶23]Philosophy triumphs easily over past evils and future evils; but present evils triumph over it.

[tr. Bund/Friswell (1871)]Philosophy easily masters past and future ills, but the sorrow of the moment is the master of philosophy.

[tr. Heard (1917)]Philosophy easily conquers both past and future misfortunes, but is conquered by the misfortunes of the moment.

[tr. Stevens (1939)]Philosophy can easily triumph over past misfortunes and over those that lie ahead: but the misfortunes of the present will triumph over our philosophy.

[tr. FitzGibbon (1957)]Philosophy triumphs with ease over misfortunes past and to come, but present misfortunes triumph over it.

[tr. Kronenberger (1959)]Philosophy triumphs easily over past and future evils; but present evils triumph over it.

[tr. Whichello (2016)]

We know that the whole creation is groaning together and suffering labor pains up until now. And it’s not only the creation. We ourselves who have the Spirit as the first crop of the harvest also groan inside as we wait to be adopted and for our bodies to be set free. We were saved in hope. If we see what we hope for, that isn’t hope. Who hopes for what they already see? But if we hope for what we don’t see, we wait for it with patience.

[οἴδαμεν γὰρ ὅτι πᾶσα ἡ κτίσις συστενάζει καὶ συνωδίνει ἄχρι τοῦ νῦν· οὐ μόνον δέ, ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτοὶ τὴν ἀπαρχὴν τοῦ πνεύματος ἔχοντες, ἡμεῖς καὶ αὐτοὶ ἐν ἑαυτοῖς στενάζομεν υἱοθεσίαν ἀπεκδεχόμενοι, τὴν ἀπολύτρωσιν τοῦ σώματος ἡμῶν. τῇ γὰρ ἐλπίδι ἐσώθημεν· ἐλπὶς δὲ βλεπομένη οὐκ ἔστιν ἐλπίς· ὃ γὰρ βλέπει τίς ἐλπίζει; εἰ δὲ ὃ οὐ βλέπομεν ἐλπίζομεν, δι᾽ ὑπομονῆς ἀπεκδεχόμεθα.]

The Bible (The New Testament) (AD 1st - 2nd C) Christian sacred scripture

Romans 8: 22-25 [CEB (2011)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now. And not only they, but ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the redemption of our body. For we are saved by hope: but hope that is seen is not hope: for what a man seeth, why doth he yet hope for? But if we hope for that we see not, then do we with patience wait for it.

[KJV (1611)]From the beginning till now the entire creation, as we know, has been groaning in one great act of giving birth; and not only creation, but all of us who possess the first-fruits of the Spirit, we too groan inwardly as we wait for our bodies to be set free. For we must be content to hope that we shall be saved -- our salvation is not in sight, we should not have to be hoping for it if it were -- but, as I say, we must hope to be saved since we are not saved yet -- it is something we must wait for with patience.

[JB (1966)]We are well aware that the whole creation, until this time, has been groaning in labour pains. And not only that: we too, who have the first-fruits of the Spirit, even we are groaning inside ourselves, waiting with eagerness for our bodies to be set free. In hope, we already have salvation; in hope, not visibly present, or we should not be hoping -- nobody goes on hoping for something which is already visible. But having this hope for what we cannot yet see, we are able to wait for it with persevering confidence.

[NJB (1985)]For we know that up to the present time all of creation groans with pain, like the pain of childbirth. But it is not just creation alone which groans; we who have the Spirit as the first of God's gifts also groan within ourselves as we wait for God to make us his children and set our whole being free. For it was by hope that we were saved; but if we see what we hope for, then it is not really hope. For who of us hopes for something we see? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

[GNT (1992 ed.)]We know that the whole creation has been groaning together as it suffers together the pains of labor, and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope, for who hopes for what one already sees? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]

Pain is a byproduct of life. That’s the truth. Life sometimes sucks. That’s true for everyone. But if you don’t face the pain and the suck, you don’t ever get the other things either. Laughter. Joy. Love. Pain passes, but those things are worth fighting for. Worth dying for.

Jim Butcher (b. 1971) American author

(Attributed)

Often cited to the short story "Vignette" (also known as "Publicity and Advertising"), but not found there.

The pain passes, but the beauty remains.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) French Impressionist artist

(Attributed, 1919)

(Source)

Quoted in Sisley Huddleston, Paris Salons, Cafés, Studios (1928). When asked by a young Henri Matisse why he still painted when suffering from painful, twisting arthritis in his hands.

When the torrent sweeps the man against a boulder, you must expect him to scream, and you need not be surprised if the scream is sometimes a theory. Shelley, chafing at the Church of England, discovered the cure of all evils in universal atheism. Generous lads irritated at the injustices of society, see nothing for it but the abolishment of everything and Kingdom Come of anarchy. Shelley was a young fool; so are these cocksparrow revolutionaries. But it is better to be a fool than to be dead. It is better to emit a scream in the shape of a theory than to be entirely insensible to the jars and incongruities of life and take everything as it comes in a forlorn stupidity.

TITUS: These words are razors to my wounded heart.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Titus Andronicus, Act 1, sc. 4, l. 320 (1.4.320) (c. 1590)

(Source)

Quite often, people who mean well will inquire of me whether I ever ask myself, in the face of my diseases, “Why me?” I never do. If I ask “Why me?” as I am assaulted by heart disease and AIDS, I must ask “Why me?” about my blessings, and question my right to enjoy them. The morning after I won Wimbledon in 1975 I should have asked “Why me?” and doubted that I deserved the victory. If I don’t ask “Why me?” after my victories, I cannot ask “Why me?” after my setbacks and disasters.

He who fears he shall suffer, already suffers what he fears.

[Qui craint de souffrir, il souffre desja de ce qu’il craint.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 3, ch. 13 (3.13), “Of Experience [De l’Experience] (1587) [tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]

(Source)

This essay first appeared in the 2nd edition (1588); this passage was added for the 3rd edition (1595).

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Who feareth to suffer, suffereth alreadie, because he feareth.

[tr. Florio (1603)]Who fears to suffer, does already suffer what he fears.

[tr. Cotton (1686)]He who dreads suffering already suffers what he dreads.

[tr. Ives (1925)]He who fears he shall suffer, already suffers because of his fear.

[tr. Zeitlin (1934)]He who fears he will suffer, already suffers from his fear.

[tr. Frame (1943)]He who is afraid of suffering already suffers from his own fears.

[tr. Cohen (1958)]A man who fears suffering is already suffering from what he fears.

[Source (1958)]Anyone who is afraid of suffering suffers already of being afraid.

[tr. Screech (1987)]

No pain, no palm;

No thorns, no throne;

No gall, no glory;

No cross, no crown.William Penn (1644-1718) English writer, philosopher, politician, statesman

“No Cross, No Crown” (1682)

Originally written while a prisoner in the Tower of London (1668-69). See Quarles (1621), Breton (1577).

The least pain in our little finger gives more concern and uneasiness than the destruction of millions of our fellow beings.

William Hazlitt (1778-1830) English writer

Essay (1829-10), “American Literature — Dr. Channing,” Edinburgh Review, Vol. 50, No. 99, Art. 7

(Source)

The price for absolute freedom from necessity is, in a sense, life itself, or rather the substitution of vicarious life for real life. […] The human condition is such that pain and effort are not just symptoms which can be removed without changing life itself; they are the modes in which life itself, together with the necessity to which it is bound, makes itself felt. For mortals, the “easy life of the gods” would be a lifeless life.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) German-American philosopher, political theorist

The Human Condition, Part 3 “Labor,” ch. 16 (1958)

(Source)

The Sting of a Reproach is the Truth of it.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs (compiler), # 4769 (1732)

(Source)

Morality turns on whether the pleasure precedes or follows the pain. Thus it is immoral to get drunk because the headache comes after the drinking. But if the headache came first and the drunkenness afterwards, it would be moral to get drunk.

Samuel Butler (1835-1902) English novelist, satirist, scholar

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler, “Morality” (1912)Full text.

Zeus, who guided mortals to be wise,

has established his fixed law —

wisdom comes through suffering.

Trouble, with its memories of pain,

drips in our hearts as we try to sleep,

so men against their will

learn to practice moderation.

Favours come to us from gods

seated on their solemn thrones —

such grace is harsh and violent.τὸν φρονεῖν βροτοὺς ὁδώ-

σαντα, τὸν [πάθει μάθος]

θέντα κυρίως ἔχειν.

στάζει δ’ ἀνθ’ ὕπνου πρὸ καρδίας

μνησιπήμων πόνος· καὶ παρ’ ἄ-

κοντας ἦλθε σωφρονεῖν.

δαιμόνων δέ που χάρις βίαιος

σέλμα σεμνὸν ἡμένων.Aeschylus (525-456 BC) Greek dramatist (Æschylus)

Agamemnon, ll. 175-183 [tr. Johnston (2007)]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:The first Hamilton alternate was used, slightly modified, by Robert Kennedy in his speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (4 Apr 1968). Kennedy's family used it as an epitaph on his grave Arlington National Cemetery: "Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, until in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom, through the awful grace of God."

- "It is through suffering that learning comes." [In Arnold Toynbee, "Christianity and Civilization" (1947), Civilization on Trial (1948)]

- "God, whose law it is that he who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despite, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God." [tr. Hamilton (1930)]

- "Guide of mortal man to wisdom, he who has ordained a law, knowledge won through suffering. Drop, drop -- in our sleep, upon the heart sorrow falls, memory’s pain, and to us, though against our very will, even in our own despite, comes wisdom by the awful grace of God." [tr. Hamilton (1937)]

See here for more discussion.

I set down in my notebooks, not once or twice, but in a dozen places, the facts I had seen. I knew that suffering did not ennoble; it degraded. It made men selfish, mean, petty and suspicious. It absorbed them in small things. It did not make them more than men; it made them less than men.

W. Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) English novelist and playwright [William Somerset Maugham]

The Summing Up, ch. 19 (1938)

(Source)

On his experiences as a medical student and the patients he observed.

But he that dares not grasp the thorn

Should never crave the rose.

A clay pot sitting in the sun will always be a clay pot. It has to go through the white heat of the furnace to become porcelain.

Mildred W. Struven (1892-1983) American Christian Scientist, housewife

(Attributed)

Quoted by her daughter Jean Harris, Stranger in Two Worlds (1986)

If you are never scared or embarrassed or hurt, it means you never take chances.

Rosalyn Drexler (b. 1926) American visual artist, novelist, playwright, screenwriter [pseud. Julia Sorel]

See How She Runs (1978)

Based on the screenplay by Marvin Gluck. As Julia Sorrel (sometimes attrib. "Julia Soul").

Those who do not feel pain seldom think that it is felt.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) English writer, lexicographer, critic

The Rambler, #48 (1 Sep 1750)

(Source)

ROSALIND:O,

how full of briers is this working-day world!William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

As You Like It, Act 1, sc. 3, l. 11ff (1.3.11-12) (1599)

(Source)

LEONATO: For there was never a philosopher

That could endure the toothache patiently.William Shakespeare (1564-1616) English dramatist and poet

Much Ado About Nothing, Act 5, sc. 1, l. 37ff (5.1.37-38) (1598)

(Source)

For he that makes any thing his chiefest good, wherein justice or virtue does not bear a part, and sets up profit, not honesty, for the measure of his happiness; as long as he acts in conformity with his own principles, and is not overruled by the mere dictates of reason and humanity, can never do the offices of friendship, justice, or liberality: nor can he ever be a man of courage, who thinks that pain is the greatest evil; or he of temperance, who imagines pleasure to be the sovereign good.

[Nam qui summum bonum sic instituit, ut nihil habeat cum virtute coniunctum, idque suis commodis, non honestate metitur, hic, si sibi ipse consentiat et non interdum naturae bonitate vincatur neque amicitiam colere possit nec iustitiam nec liberalitatem; fortis vero dolorem summum malum iudicans aut temperans voluptatem summum bonum statuens esse certe nullo modo potest.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Officiis [On Duties; On Moral Duty; The Offices], Book 1, ch. 2 (1.2) / sec. 5 (44 BC) [tr. Cockman (1699)]

(Source)

Attacking the Epicurean "highest good" of avoiding pain and seeking personal detachment; Cicero supported the Stoic virtues of courage and moderation.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:He who teaches that to be the chief good which hath no connection with virtue, which is measured by personal advantage, and not by honor; if he be consistent with himself, and not sometimes overcome by the benignity of nature, can neither cultivate friendship nor practice justice nor liberality. That man cannot be brave who believes pain the greatest evil; nor temperate, who believes pleasure the supreme good.

[tr. McCartney (1798)]For if a man should lay down as the chief good, that which has no connexion with virtue, and measure it by his own interests, and not according to its moral merit; if such a man shall act consistently with his own principles, and is not sometimes influenced by the good ness of his heart, he can cultivate neither friendship, justice, nor generosity. In truth, it is impossible for the man to be brave who shall pronounce pain to be the greatest evil, or temperate who shall propose pleasure as the highest good.