The individualism which finds its expression in the abuse of physical force is checked very early in the growth of civilization, and we of to-day should in our turn strive to shackle or destroy that individualism which triumphs by greed and cunning, which exploits the weak by craft instead of ruling them by brutality.

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) American politician, statesman, conservationist, writer, US President (1901-1909)

Speech (1910-04-23), “Citizenship in a Republic [The Man in the Arena],” Sorbonne, Paris

(Source)

Quotations about:

greed

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

Money is miraculous. What miraculous facilities has it yielded, will it yield us; but also what never-imagined confusions, obscurations has it brought in; down almost to total extinction of the moral-sense in large masses of mankind!

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

Past and Present, Book 3, ch. 10 “Plugson of Undershot” (1843)

(Source)

It is an insanity to get more than you want. Imagine a man in this city, an intelligent man, say with two or three millions of coats, eight or ten millions of hats, vast warehouses full of shoes, billions of neckties, and imagine that man getting up at four o’clock in the morning, in the rain and snow and sleet, working like a dog all day to get another necktie! Is not that exactly what the man of twenty or thirty millions, or of five millions, does to-day? Wearing his life out that somebody may say, “How rich he is!”

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

Speech (1886-11-14), “A Lay Sermon,” American Secular Union annual congress, Chickering Hall, New York City

(Source)

Avarice iz like a grave yard, it takes all that it kan git, and givs nothing back.

[Avarice is like a graveyard; it takes all that it can get, and gives nothing back.]

Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 150 “Affurisms: Parboils” (1874)

(Source)

In vain do they think themselves innocent who appropriate to their own use alone those goods which God gave in common; by not giving to others that which they themselves receive, they become homicides and murderers, inasmuch as in keeping for themselves those things which would have alleviated the sufferings of the poor, we may say that they every day cause the death of as many persons as they might have fed and did not.

Gregory I (c. 540 - 604) Bishop of Rome, liturgist, Latin Father, Doctor of the Church [Gregorius I, Saint Gregory the Great, Saint Gregory the Dialogist]

(Attributed)

(Source)

Quoted in George D. Herron, Between Caesar and Jesus, ch. 4 "Christian Doctrine and Private Property" (1899).

The Rich knowes not who is his friend.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

Jacula Prudentum, or Outlandish Proverbs, Sentences, &c. (compiler), # 865 (1640 ed.)

(Source)

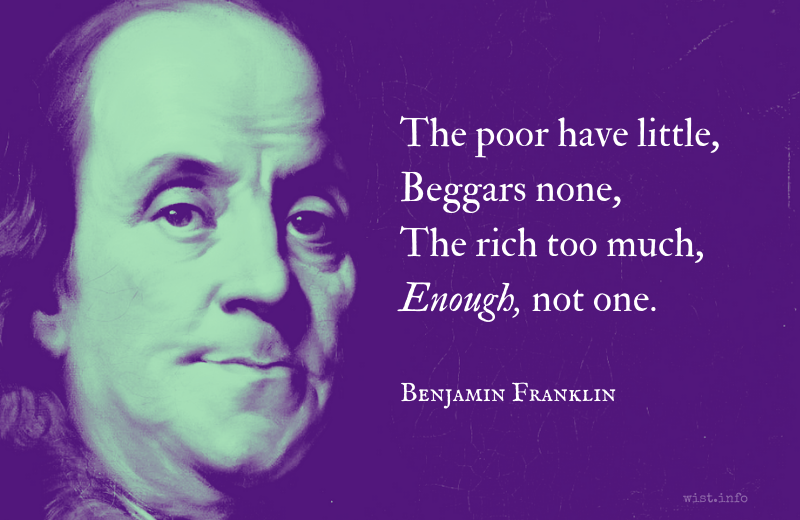

If you desire many things, many things will seem but a few.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1736 ed.)

(Source)

CYCLOPS: Little man, the wise regard wealth as the god to worship; all else is just prating and fine-sounding sentiments.

[ΚΥΚΛΩΨ: ὁ πλοῦτος, ἀνθρωπίσκε, τοῖς σοφοῖς θεός,

τὰ δ᾽ ἄλλα κόμποι καὶ λόγων εὐμορφία.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Cyclops [Κύκλωψ], l. 316ff (c. 424-23 BC) [tr. Kovacs (1994)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:POLYPHEME:Vile caitiff,

Wealth is the deity the wise adore,

But all things else are unsubstantial boasts,

And specious words alone.

[tr. Wodhull (1809)]CYCLOPS: Wealth, my good fellow, is the wise man's God, All other things are a pretence and boast.

[tr. Shelley (1824)]CYCLOPS: Wealth, manikin, is the god for the wise; all else is mere vaunting and fine words.

[tr. Coleridge (1913)]CYCLOPS: Wealth, master Shrimp, is to the truly wise

The one true god; the rest are mockeries

Of tall talk, naught but mere word-pageantries.

[tr. Way (1916)]

As wealth grows, worry grows, and thirst for more wealth.

[Crescentem sequitur cura pecuniam,

Maiorumque fames.]Horace (65-8 BC) Roman poet and satirist [Quintus Horacius Flaccus]

Odes [Carmina], Book 3, # 16, l. 17ff (3.16.17-18) (23 BC) [tr. Michie (1963)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:With growing riches cares augment,

And thirst of greater.

[tr. Fanshawe; ed. Brome (1666)]Care still attends encreasing store,

And craving Appetite for more

[tr. Creech (1684)]As riches grow, care follows: men repine

And thirst for more.

[tr. Conington (1872)]Care, and a thirst for greater things, is the consequence of increasing wealth.

[tr. Smart/Buckley (1853)]But as wealth into our coffers flows in still increasing store,

So, too, still our care increases, and the hunger still for more.

[tr. Martin (1864)]Care grows with wealth, with wealth the greed for more.

[tr. Bulwer-Lytton (1870)]The care of wealth, together with the thirst for more, attend increasing riches.

[tr. Elgood (1893)]But care with growing treasure grows,

And thirst for more.

[tr. Gladstone (1894)]Wealth, the faster it grows, is but the prey of care,

And of lusting for more.

[tr. Phelps (1897)]Care follows growing wealth, and thirst for more.

[tr. Garnsey (1907)]As riches grow, care follows, and a thirst

For more and more.

[tr. Marshall (1908)]Yet as money grows, care and greed for greater riches follow after.

[tr. Bennett (Loeb) (1912)]Increase of wealth and greed bring on

Care.

[tr. Mills (1924)]But gold brings both greed and

Trouble on its back.

[tr. Raffel (1983)]The more the money grows the more the greed

Grows too; also the anxiety of greed.

[tr. Ferry (1997)]But with increasing wealth, follow

anxiety and greed for more and more.

[tr. Alexander (1999)]Anxiety, and the hunger for more, pursues

growing wealth.

[tr. Kline (2015)]

Gradually we become tired of the old, of what we safely possess, and we stretch out our hands again. Even the most beautiful scenery is no longer assured of our love after we have lived in it for three months, and some more distant coast attracts our avarice: possessions are generally diminished by possession.

[Wir werden des Alten, sicher Besessenen allmählich überdrüssig und strecken die Hände wieder aus; selbst die schönste Landschaft, in der wir drei Monate leben, ist unserer Liebe nicht mehr gewiss, und irgend eine fernere Küste reizt unsere Habsucht an: der Besitz wird durch das Besitzen zumeist geringer.]Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) German philosopher and poet

The Gay Science [Die fröhliche Wissenschaft], Book 1, § 14 (1882) [tr. Kaufmann (1974)]

(Source)

Also known as La Gaya Scienza, The Joyful Wisdom, or The Joyous Science.

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:We gradually become satiated with the old, the securely possessed, and again stretch out our hands; even the finest landscape in which we live for three months is no longer certain of our love, and any kind of more distant coast excites our covetousness: the possession for the most part becomes smaller through possessing.

[tr. Common (1911)]We slowly grow tired of the old, of what we safely possess, and we stretch our our hands again; even the most beautiful landscape is no longer sure of our love after we have lived in it for three months, and some more distant coast excites our greed: possession usually diminishes the possession.

[tr. Nauckhoff (2001)]We gradually grow weary of the old, familiar things we securely hold, and again stretch forth our hands; even the most beautiful landscape lived in for three months is no longer assured of our love, and some more distant shore excites our avarice: what is had loses much in the having.

[tr. Hill (2018)]

Greed is not good. Being rapacious doesn’t make you a capitalist, it makes you a sociopath. And in an economy as dependent upon cooperation at scale as ours, sociopathy is as bad for business as it is for society.

Nick Hanauer (b. 1959) American entrepreneur and venture capitalist [Nicolas Joseph Hanauer]

Lecture (2019-07) “The Dirty Secret of Capitalism — and a New Way Forward,” TEDsummit, Edinburgh

(Source)

(Source (Video), 14:19)

Who are the greedy? Those who are not satisfied with what suffices for their own needs. Who are the robbers? Those who take for themselves what rightfully belongs to everyone. And you, are you not greedy? Are you not a robber? The things you received in trust as a stewardship, have you not appropriated them for yourself? Is not the person who strips another of clothing called a thief? And those who do not clothe the naked when they have the power to do so, should they not be called the same? The bread you are holding back is for the hungry, the clothes you keep put away are for the naked, the shoes that are rotting away with disuse are for those who have none, the silver you keep buried in the earth is for the needy. You are thus guilty of injustice toward as many as you might have aided, and did not.

Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-378) Christian bishop, theologian, monasticist, Doctor of the Church [Saint Basil the Great, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας]

“I Will Tear Down My Barns [καθελῶ μου τὰς ἀποθήκας],” Sermon # 6 [tr. Schroeder (2009)]

(Source)

He is not poore that hath little, but he that desireth much.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

Jacula Prudentum, or Outlandish Proverbs, Sentences, &c. (compiler), # 309 (1640 ed.)

(Source)

Poverty wants some things, Luxury many things, Avarice all things.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1735 ed.)

(Source)

Man never gives up his desire for gain and aggrandizement; as death draws near, a prey to bile, with withered face and palsied legs, he will speak of my fortune, my situation.

[L’on ne se rend point sur le désir de posséder et de s’agrandir: la bile gagne, et la mort approche, qu’avec un visage flétri, et des jambes déjà faibles, l’on dit: ma fortune, mon établissement.]Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 6 “Of Gifts of Fortune [Des Biens de Fortune],” § 51 (6.51) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:There is no end to a Man's desire of growing rich and great; when the Cough seizes him, when Death approaches, his Face shrivel'd, and his Legs weak, he cries, My Fortune, my Establishment.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]There is no end to a Man's Desire of growing rich and great; the Cough seizes him, Death approaches, his Face is shrivel'd, and his Legs weak, yet he cries, My Fortune, my Preferment.

[Curll ed. (1713)]There is no end of desiring Riches and Grandeur; before the Rattle seizes him, and Death approaches, though his Face be shriveled, and his Legs totter, yet he is ever talking of, my Fortune, my Preferment.

[Browne ed. (1752)]All that a man wishes for is riches and grandeur; he falls very ill, and death draws near, and though his face be shrivelled and his legs totter, yet he is still talking of his fortune and his post.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

When will the Miser’s Chest be full enough?

When will he cease his Bags to cram and stuff?

All Day he labours and all Night contrives,

Providing as if he’d an hundred Lives.

While endless Care cuts short the common Span:

So have I seen with Dropsy swoln, a Man,

Drink and drink more, and still unsatisfi’d,

Drink till Drink drown’d him, yet he thirsty dy’d.Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1735 ed.)

(Source)

If he is poor who is full of Desires, nothing can equal the Poverty of the Ambitious and the Covetous.

[S’il est vrai que l’on soit pauvre par toutes les choses que l’on désire, l’ambitieux et l’avare languissent dans une extrême pauvreté.]Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 6 “Of Gifts of Fortune [Des Biens de Fortune],” § 49 (6.49) (1688) [Browne ed. (1752)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:If he is only poor who desires much, and is always in want; the Ambitious and the Covetous languish in extreme Poverty.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]If a Man is poor, by all the things which he longs for, the Ambitious and Covetous languish in extreme Poverty.

[Curll ed. (1713)]If a man be poor who wishes to have everything, then an ambitious and a miserly man languish in extreme poverty.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]If it is true that poverty consists in desiring a great many things, the ambitious man and the miser suffer from extreme poverty.

[tr. Stewart (1970)]

My days of love are over; me no more

The charms of maid, wife, and still less of widow,

Can make the fool of which they made before, —

In short, I must not lead the life I did do;

The credulous hope of mutual minds is o’er,

The copious use of claret is forbid too,

So for a good old-gentlemanly vice,

I think I must take up with avarice.

A shrewd man has to arrange his interests in order of importance and deal with them one by one; but often our greed upsets this order and makes us run after so many things at once that through over-anxiety to have the trivial we miss the most important.

[Un habile homme doit régler le rang de ses intérêts et les conduire chacun dans son ordre. Notre avidité le trouble souvent en nous faisant courir à tant de choses à la fois que, pour désirer trop les moins importantes, on manque les plus considérables.]

François VI, duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680) French epigrammatist, memoirist, noble

Réflexions ou sentences et maximes morales [Reflections; or Sentences and Moral Maxims], ¶66 (1665-1678) [tr. Tancock (1959)]

(Source)

Present in the first, 1665 edition in a slightly longer form:Un habile homme doit savoir régler le rang de ses intérêts et les conduire chacun dans son ordre. Notre avidité le trouble souvent en nous faisant courir à tant de choses à la fois que, pour désirer trop les moins importantes, nous ne les faisons pas assez servir à obtenir les plus considérables.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:In this the prudent man is distinguishable from the imprudent, that he regulates his interests, and directs them to the prosecution of his designs each in their order. Our earnestness does many times raise a disturbance in them, by hurrying us after a hundred things at once. Thence it proceeds, that out of an excessive desire of the less important, we do not what is requisite for the attainment of the most considerable.

[tr. Davies (1669), ¶165]A wise Man should order his Designs, and set all his Interests in their proper places. This Order is often disturbed by a foolish greediness, which, while it puts us upon pursuing several things at once, makes us eager for matters of less consideration; and while we grasp at trifles, we let go things of greater Value.

[tr. Stanhope (1694), ¶67]An able man will arrange his interests, and conduct each in its proper order. Our greediness often hurts us, by making us prosecute so many things at once; by too earnestly desiring the less considerable, we lose the more important.

[pub. Donaldson (1783), ¶205; ed. Lepoittevin-Lacroix (1797), ¶65]An able man will arrange his respective interests;, and conduct each in its proper order. Ambition is often injurious, by tempting us to prosecute too much at once. By earnestly desiring the less considerable, we lose the more important.

[ed. Carville (1835), ¶473]A clever man should regulate his interests, and place them in proper order. Our avidity often deranges them by inducing us to undertake too many things at once; and by grasping at minor objects, we lose our hold of more important ones.

[ed. Gowens (1851), ¶67]A clever man ought to so regulate his interests that each will fall in due order. Our greediness so often troubles us, making us run after so many things at the same time, that while we too eagerly look after the least we miss the greatest.

[tr. Bund/Friswell (1871)]A wise man co-ordinates his interests, and develops them according to their merits. Cupidity defeats its own ends by following so many at once that in our greed for trifles we lose sight of important matters.

[tr. Heard (1917)]A clever man will know how to range his interests, and will pursue each according to its merits. Our greed, however, will often confuse our method; for we run after so many things at once that we frequently miss what is of importance in pursuit of what is negligible.

[tr. FitzGibbon (1957)]Clever men should arrange their desires in the proper order and seek each in turn. In our eagerness we often attempt too many things at once, and by striving too much after the small ones we lose the big.

[tr. Kronenberger (1959)]A wise man ought to arrange his interests in their true order of importance. Our greed often disturbs this order by making us pursue so many things at once that, for too much desiring the least important, we miss those that are most so.

[tr. Whichello (2016)]

“But whom do I treat unjustly,” you say, “by keeping what is my own?” Tell me, what is your own? What did you bring into this life? From where did you receive it? It is as if someone were to take the first seat in the theater, then bar everyone else from attending, so that one person alone enjoys what is offered for the benefit of all in common — this is what the rich do. They seize common goods before others have the opportunity, then claim them as their own by right of preemption. For if we all took only what was necessary to satisfy our own needs, giving the rest to those who lack, no one would be rich, no one would be poor, and no one would be in need.

[Καὶ ποῖον, λέγει, ἀδικῶ, μὲ τὸ νὰ κρατῶ γιὰ τoν ἐαυτόν μου αὐτὰ ποῦ μου ἀνήκουν; Ποία, εἰπέ μου, εἶναι αὐτὰ ποῦ σου ἀνήκουν; Ἀπὸ ποῦ τὰ ἔλαβες, καὶ τὰ ἔφερες στὴν ζωὴν αὐτήν; Ὅπως ἀκριβῶς κάποιος ποὺ εὑρίσκει στὸ θέατρο θέση μὲ καλὴν θέαν, ἐμποδίζει ἔπειτα τοὺς εἰσερχομένους, θεωρώντας ὡς ἰδικὸ τοῦ αὐτὸ ποὺ προορίζεται γιὰ χρῆσιν κοινήν, ἔτσι εἶναι καὶ οἱ πλούσιοι. Ἀφοῦ ἐκυρίευσαν ἐκ τῶν προτέρων τα κοινὰ ἀγαθά, τὰ ἰδιοποιοῦνται ἁπλῶς ἐπειδὴ τὰ ἐπρόλαβαν. Ἐὰν ὁ καθένας ἐκρατοῦσε ἐκεῖνο ποὺ ἀρκεῖ γιὰ τὴν ἱκανοποίηση τῶν ἀναγκῶν του, καὶ ἄφηνε τὸ περίσσευμα σ’ αὐτὸν ποὺ τὸ χρειάζεται, κανεὶς δὲν θὰ ἦταν πλούσιος, ἀλλὰ καὶ κανεὶς πτωχός.]

Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-378) Christian bishop, theologian, monasticist, Doctor of the Church [Saint Basil the Great, Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας]

“I Will Tear Down My Barns [καθελῶ μου τὰς ἀποθήκας],” Sermon # 6 [tr. Schroeder (2009)]

(Source)

In C. Paul Schroeder, ed., Saint Basil on Social Justice (2009).

This is that same Foulon named âme damnée du Parlement; a man grown gray in treachery, in griping, projecting, intriguing and iniquity: who once when it was objected, to some finance-scheme of his, “What will the people do?” — made answer, in the fire of discussion, “The people may eat grass”: hasty words, which fly abroad irrevocable, — and will send back tidings!

Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) Scottish essayist and historian

The French Revolution: A History, Part 1, Book 3, ch. 9 (1.3.9) (1837)

(Source)

Writing of Joseph-François Foullon de Doué (1715-1789), French politician, the "damned soul of the Parliament," and a Controller-General of Finances under Louis XVI. Widely hated by "the people" for such statements and actions, he was one of the early targets of the French Revolution, as told in Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities. He was marched from his country hiding place back to Paris, with the mob shoving grass and hay into his face and mouth. He became the first recorded person to have been lynched from a lamp post. (The rope broke three times, so he was instead beheaded and his grass-stuffed head marched about on a pike.)

He does not possess Wealth, it possesses him.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard (1734 ed.)

(Source)

In truth, it is not want, but rather abundance, that breeds avarice.

[De vray, ce n’est pas la disette, c’est plustost l’abondance qui produict l’avarice.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 1, ch. 14 “The Taste of Good and Bad Things Depends Mostly on the Opinion We Have of Them [Que le goust des biens et des maux despend en bonne partie de l’opinion que nous en avons]” (1572) (1.14) (1595) [tr. Frame (1943)]

(Source)

Though this chapter was written around 1572 for the 1580 edition, this text was added for the 1588 edition. The chapter as a whole was numbered ch. 14 in the 1580 and 1588 editions, moved to ch. 40 for the 1595 ed. Most modern translations use the original numbering.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Verily, it is not want, but rather plenty that causeth avarice.

[tr. Florio (1603), ch. 40]In plain truth, it is not Want, but rather Abundance, that Creates Avarice.

[tr. Cotton (1686), ch. 40]In truth, it is not want, but rather abundance, that creates avarice.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877), ch. 40]In truth, it is not want, but rather abundance, which gives birth to avarice.

[tr. Ives (1925)]And truly it is not want that produces avarice but plenty.

[tr. Screech (1987)]Truly, abundance rather than want causes stinginess.

[tr. HyperEssays (2023)]

Let us not envy a certain class of men for their enormous riches; they have paid such an equivalent for them that it would not suit us; they have given for them their peace of mind, their health, their honour, and their conscience; this is rather too dear, and there is nothing to be made out of such a bargain.

[N’envions point à une sorte de gens leurs grandes richesses; ils les ont à titre onéreux, et qui ne nous accommoderait point: ils ont mis leur repos, leur santé, leur honneur et leur conscience pour les avoir; cela est trop cher, et il n’y a rien à gagner à un tel marché.]Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 6 “Of Gifts of Fortune [Des Biens de Fortune],” § 13 (6.13) (1688) [tr. Van Laun (1885)]

(Source)

One translator suggestions the "certain class of men" refers to the partisans, or tax-farmers: private tax collectors, often of humble origin, who purchased the right to their job, and were notorious for turning tax collection into a profitable profession.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Let us not envy some Men their great Riches; their Burthens would be too heavy for us; we cou'd not Sacrifice, as they do, Health, Quiet, Honour and Conscience, to obtain 'em: 'Tis to pay so dear for them that there is nothing to be got by the Bargain.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]Let us not envy some Men their great Riches, their burden would be too heavy for us; we cou'd not sacrifice, as they do, Health, Quiet, Honour and Conscience, to obtain 'em: 'Tis to pay so dear for 'em, that there is nothing to be got by the Bargain.

[Curll ed. (1713)]Let us not envy some Men their accountable Riches; their Burthen would be too heavy for us; we could not sacrifice, as they do, Health, Quiet, Honour and Conscience, to obtain them. It is to pay so dear for them, that the Bargain is a Loss.

[Browne ed. (1752)]We need not envy certain people their great wealth; they acquired it at a heavy cost, which would not suit us; they staked their rest, their health, their honour and their conscience to acquire it; the price is too high, and there is nothing to be gained by such a bargain.

[tr. Stewart (1970)]

When all sinnes grow old, coveteousnesse is young.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

Jacula Prudentum, or Outlandish Proverbs, Sentences, &c. (compiler), # 18 (1640 ed.)

(Source)

To what extremes, O cursèd lust for gold

will you not drive man’s appetite?

[Per che non reggi tu, o sacra fame

de l’oro, l’appetito de’ mortali?]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 2 “Purgatorio,” Canto 22, l. 40ff (22.40-41) [Statius] (1314) [tr. Musa (1981)]

(Source)

Statius is quoting Virgil (whose shade stands in front of him) from The Aeneid, Book 3, ll. 56-57:Quid non mortalia pectora cogis,

Auri sacra fames?

Unlike the phrase in that pagan book, which is purely about the corrupting power of greed and gold-lust, Dante's Italian and some translators make reference to a "holy hunger," a virtue/rule of proper attitude toward money and spending, criticized here for it not restraining humans from the sins of being either spendthrifts or misers -- a nod to Aristotle making sin about extremes and virtue about moderation. See Ciardi, Durling, Kirkpatrick, Princeton, and Sayers for more discussion.

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:Why, thou cursed thirst

Of gold! dost not with juster measure guide

The appetite of mortals?

[tr. Cary (1814)]Why should'st thou not restrain accursèd thirst

Of gold, the appetite of mortals lost?

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]To what impellest thou not, O cursed hunger

Of gold, the appetite of mortal men?

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]Why restrainest thou not, O holy hunger of gold, the desire of mortals?

[tr. Butler (1885)]To what lengths, O thou cursed thirst of gold,

Dost thou not rule the mortal appetite?

[tr. Minchin (1885)]O cursed hunger of gold, to what dost thou not impel the appetite of mortals?

[tr. Norton (1892)]Wherefore dost thou not regulate the lust of mortals, O hallowed hunger of gold?

[tr. Okey (1901)]To what, O cursed hunger for gold, dost thou not drive the appetite of mortals?

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]O hallowed hunger of gold, why dost thou not

The appetite of mortal men control?

[tr. Binyon (1943)]With what constraint constran'st thou not the lust

Of mortals, thou devoted greed of gold!

[tr. Sayers (1955)]To what do you not drive man's appetite,

O cursèd gold-lust!

[tr. Ciardi (1961)]Why do you not control the appetite

Of mortals, O you accurst hunger for gold?

[tr. Sisson (1981)]Why cannot you, o holy hunger

for gold, restrain the appetite of mortals?

[tr. Mandelbaum (1982)]O sacred hunger for gold, why do you not rule human appetite?

[tr. Kline (2002)]Why do you, O holy hunger for gold, not

govern the appetite of mortals?

[tr. Durling (2003)]You, awestruck hungering for gold! Why not

impose a rule on mortal appetite?

[tr. Kirkpatrick (2007)]To what end, O cursèd hunger for gold,

do you not govern the appetite of mortals?

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]Accursed craving for money, what is there, in

This world, you don't lead human beings to?

[tr. Raffel (2010)]

How far, O rich, do you extend your senseless avarice? Do you intend to be the sole inhabitants of the earth? Why do you drive out the fellow sharers of nature, and claim it all for yourselves? The earth was made for all, rich and poor, in common. Why do you rich claim it as your exclusive right? The soil was given to the rich and poor in common — wherefore, oh, ye rich, do you unjustly claim it for yourselves alone? Nature gave all things in common for the use of all; usurpation created private rights. Property hath no rights. The earth is the Lord’s, and we are his offspring. The pagans hold earth as property. They do blaspheme God.

Ambrose of Milan (339-397) Roman theologian, statesman, Christian prelate, saint, Doctor of the Church [Aurelius Ambrosius]

(Attributed)

Frequently quoted in the early 20th Century in various social justice writings, and in the years since then, but all citations I can find fall back to its inclusion in Upton Sinclair, The Cry for Justice, Book 8 "The Church" (1915) (though it can be found somewhat earlier than that).

Why, if all the rich men in the world divided up their money amongst themselves, there wouldn’t be enough to go round!

Christina Stead (1902-1983) Australian writer

House of All Nations, sc. 12 “The Revolution” [Jules] (1938)

(Source)

Pooh-poohing the idea that confiscating wealth from the rich would provide enough money to the poor. The line is also included in the "Credo" at the beginning of the novel, attributed to the character, Jules Bertillon.

Whilst that for which all virtue now is sold,

And almost every vice, almighty gold ….Ben Jonson (1572-1637) English playwright and poet

“Epistle to Elizabeth, Countess of Rutland” (1599)

(Source)

Reprinted in The Forest, Poem 12.

The least vile of all merchants is he who says: “Let us be virtuous, since, thus, we shall gain much more money than the fools who are dishonest.” For the merchant, even honesty is a financial speculation.

[Le moins infâme de tous les commerçants, c’est celui qui dit: Soyons vertueux pour gagner beaucoup plus d’argent que les sots qui sont vicieux. — Pour le commerçant, l’honnêteté elle-même est une spéculation de lucre.]

Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) French poet, essayist, art critic

Journaux Intimes [Intimate Journals], “Mon cœur mis à nu [My Heart Laid Bare],” § 47 (1864–1867; pub. 1887) [tr. Isherwood (1930)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translation:The least despicable of merchants is the one who says: Let us be virtuous so that we can make far more money than those vice-ridden fools. -- For the merchant, even honesty offers a money-making opportunity.

[tr. Sieburth (2022)]

How deep is evil rooted in the breasts

Of all men! tho’ our pardon we extend not

To him, who, grasping at some great reward,

Becomes a sinner: yet since, in proportion

As he grows boldly profligate, he reaps

Greater advantages, he with more ease

The world’s reproachful language may sustain.[ὡς ἔμφυτος μὲν πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις κάκη”

ὅστις δὲ πλεῖστον μισϑὸν εἰς χεῖρας λαβὼν

κακὸς γένηται, τῷδε συγγνώμη μὲν οὔ,

πλείω δὲ μισϑὸν μείζονος τόλμης ἔχων

τὸν τῶν λεγόντων ῥᾷον ἂν φέροι Ῥόγον.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Bellerophon [Βελλεροφῶν], frag. 297 (TGF) (c. 430 BC) [tr. Wodhull (1809)]

(Source)

Nauck frag. 299. Barnes frag. 44, Musgrave frag. 9. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:All men have badness in their natures! The one who takes most pay into his hands, and proves bad, gets no pardon; but if he has more pay for greater audacity, he'll endure censorious talk more easily.

[tr. Collard, Hargreaves, Cropp (1995)]There is evil in all men. Whoever gets his hands on good money and is seen to be wicked, he is roundly condemned. But if he were yet more daring, gaining even greater reward, he would have less of a problem enduring being criticized by others.

[tr. Stevens (2012)]

But the rich man is tortured by fears, wasted with griefs, aflame with greed, never free from care, always restless and uneasy, out of breath from unending struggles with his enemies. It is true enough that he increases his holdings beyond measure by going through these miseries; but at the same time, thanks to that very increase, he also multiples his bitter cares. In contrast, the individual of moderate means is satisfied with his small and limited property; he is loved by family and friends; he enjoys sweet peace with his relations, neighbors, and friends; he is devout in his piety, benevolent of mind, sound of body, moderate in his style of life, unblemished in character, and untroubled in conscience. I do not know whether anyone would be so foolish as to have any doubt about which of the two to prefer.

[Alium praediuitem cogitemus; sed diuitem timoribus anxium, maeroribus tabescentem, cupiditate flagrantem, numquam securum, semper inquietum, perpetuis inimicitiarum contentionibus anhelantem, augentem sane his miseriis patrimonium suum in inmensum modum atque illis augmentis curas quoque amarissimas aggerantem; mediocrem uero illum re familiari parua atque succincta sibi sufficientem, carissimum suis, cum cognatis uicinis amicis dulcissima pace gaudentem, pietate religiosum, benignum mente, sanum corpore, uita parcum, moribus castum, conscientia securum. Nescio utrum quisquam ita desipiat, ut audeat dubitare quem praeferat.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

City of God [De Civitate Dei], Book 4, ch. 3 (4.3) (AD 412-416) [tr. Babcock (2012)]

(Source)

On wealth and power as the foundation for happiness.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Let my wealthy man take with him fears, sorrows, covetousness, suspicion, disquiet, contentions, making immense additions to his estate only by adding to his heap of most bitter cares; and let my poor man take with him sufficiency with little, love of kindred, neighbours, friends, joyous peace, peaceful religion, soundness of body, sincereness of heart, abstinence of diet, chastity of carriage, and security of conscience. Where should a man find any one so sottish as would make a doubt which of these to prefer in his choice?

[tr. Healey (1610)]But the rich man is anxious with fears, pining with discontent, burning with covetousness, never secure, always uneasy, panting from the perpetual strife of his enemies, adding to his patrimony indeed by these miseries to an immense degree, and by these additions also heaping up most bitter cares. But that other man of moderate wealth is contented with a small and compact estate, most dear to his own family, enjoying the sweetest peace with his kindred neighbors and friends, in piety religious, benignant in mind, healthy in body, in life frugal, in manners chaste, in conscience secure. I know not whether any one can be such a fool, that he dare hesitate which to prefer.

[ed. Dods (1871)]But, our wealthy man is haunted by fear, heavy with cares, feverish with greed, never secure, always restless, breathless from endless quarrels with his enemies. By these miseries, he adds to his possessions beyond measure, but he also piles up for himself a mountain of distressing worries. The man of modest means is content with a small and compact patrimony. He is loved by his own, enjoys the sweetness of peace, in his relations with kindred, neighbors, and friends, is religious and pious, of kindly disposition, healthy in body, self-restrained, chaste in morals, and at peace with his conscience. I wonder if there is anyone so senseless as to hesitate over which of the two to prefer.

[tr. Zema/Walsh (1950)]Let us suppose that the rich man is troubled by fears, pining with grief, burning with desire, never secure, always restless, panting in ceaseless struggles with his foes, though he does, to be sure, by dint of such suffering accumulate great additions to his estate even beyond measure, these additions adding also their quota of corrosive anxieties. Let the man of modest means, on the other hand, be self-sufficient on his trim and tiny property, beloved by his family, enjoying the most agreeable relations with his kindred, neighbours and friends, devoutly religious, kindly disposed, in good physical condition, leading a simple life, free from vice and untroubled in conscience. I don’t suppose that there is anyone so foolish as to think of doubting which one he would prefer.

[tr. Green (Loeb) (1963)]But the rich man is tortured by fears, worn out with sadness, burnt up with ambition, never knowing serenity of repose, always panting and sweating in his struggles with opponents. It may be true that he enormously swells his patrimony, but at the cost of those discontents, while by this increase he heaps up a load of further anxiety and bitterness. The other man, the ordinary citizen, is content with his strictly limited resources. He is loved by family and friends; he enjoys the blessing of peace with his relations, neighbours, and friends; he is loyal, compassionate, and kind, healthy in body, temperate in habits, of unblemished character, and enjoys the serenity of a good conscience. I do not think anyone would be fool enough to hesitate about which he would prefer.

[tr. Bettenson (1972)]The wealthy man, however, is troubled by fears; he pines with grief; he burns with greed. He is never secure; he is always unquiet and panting from endless confrontations with his enemies. To be sure, he adds to his patrimony in immense measure by these miseries; but alongside these additions he also heaps up the most bitter cares. By contrast, the man of moderate means is self-sufficient on his small and circumscribed estate. He is of his own family, and rejoices in the most sweet peace with kindred, neighbours and friends. He is devoutly religious, well disposed in mind, healthy in body, frugal in life, chaste in morals, untroubled in conscience. I do not know if anyone could be such a fool as to dare to doubt which to prefer.

[tr. Dyson (1998)]

You have reached the pinnacle of success as soon as you become uninterested in money, compliments, or publicity.

Orlando A. Battista (1917-1995) Canadian-American chemist, aphorist

Quotoons: A Speaker’s Dictionary, No. 3962 (1977 ed.)

(Source)

Often misattributed to Thomas Wolfe. More discussion about the origin of quotation: You Have Reached the Pinnacle of Success as Soon as You Become Uninterested in Money, Compliments, or Publicity – Quote Investigator®.

Money was made, not to command our Will,

But all our lawful pleasures to fulfil.

Shame and Woe to us, if we our Wealth obey;

The Horse doth with the Horseman run away.Abraham Cowley (1618-1667) English poet and essayist

“Paraphrase upon the 10th Epistle of the First Book of Horace,” l. 75ff.

(Source)

Where large sums of money are concerned, it is advisable to trust nobody.

Blind greed! Brainless rage!

In our brief lives they drive us beyond sense

And leave us misery for a heritage

Throughout eternity![Oh cieca cupidigia e ira folle,

che sì ci sproni ne la vita corta,

e ne l’etterna poi sì mal c’immolle!]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 1 “Inferno,” Canto 12, l. 49ff (12.49-51) (1309) [tr. James (2013)]

(Source)

On seeing Phlegethon, the river of boiling blood, in which those who violently injured others (through greed or wrath) are forced to stand for all eternity.

Some versions have this as something Virgil says; most make it an exclamation of Dante's.

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:O foolish Rage, O blind desire,

That spurs you on, in the short life above,

To such dire Acts as to eternity

Will keep you in this wretched bath below!

[tr. Rogers (1782), l. 45ff]O blind lust!

O foolish wrath! who so dost goad us on

In the brief life, and in the eternal then

Thus miserably o’erwhelm us.

[tr. Cary (1814)]Oh blinded lust! oh anger void of sense!

To spur us o'er the shorter life so bold,

So fell to steep us in the life immense!

[tr. Dayman (1843)]Oh blind cupidity [both wicked and foolish],

which so incites us in the short life, and then,

in the eternal, steeps us so bitterly!

[tr. Carlyle (1849)]O blind cupidity! O foolish wrath!

Thorough this short life, that spurs them to the sleep,

Eternally in tide like this to steep.

[tr. Bannerman (1850), from Virgil]Oh, blinded greediness! oh, foolish rage!

Which spur us so in the short world of life,

And then in death so drown us in despair!

[tr. Johnston (1867)]O blind cupidity, O wrath insane,

That spurs us onward so in our short life,

And in the eternal then so badly steeps us!

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]O blind covetousness! O foolish wrath! that dost so spur us in our short life, and afterward in the life eternal dost in such evil wise steep us!

[tr. Butler (1885)]O blind cupidity, O foolish ire,

Which spurs us on so in our life's short day,

And soaks us till Eternity expire!

[tr. Minchin (1885)]Oh blind cupidity, both guilty and mad, that so spurs us in the brief life, and then, in the eternal, steeps us so ill!

[tr. Norton (1892)]O sightless greed! O foolish wrath! that dost in our short life, so goad us; and after, in the life that hath no end, dost sink us in such evil plight.

[tr. Sullivan (1893), from Virgil]Oh, blind cupidity! Oh, senseless anger,

Which in the brief life spurs us on so hotly.

And in the eternal then so sadly dips us !

[tr. Griffith (1908)]O blind covetousness and foolish anger, which in the brief life so goad us on and then, in the eternal, steep us in such misery!

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]O blind greed and mad anger, all astray

That in the short life goad us onward so,

And in the eternal with such plungings pay!

[tr. Binyon (1943)]O blind, O rash and wicked lust of spoil,

That drives our short life with so keen a goad

And steeps our life eternal in such broil!

[tr. Sayers (1949)]Oh blind!

Oh ignorant, self-seeking cupidity

which spurs us so in the short mortal life

and steeps us so through all eternity!

[tr. Ciardi (1954)]O blind cupidity and mad rage, which in the brief life so goad us on, and then, in the eternal, steep us so bitterly!

[tr. Singleton (1970)]O blind cupidity and insane wrath,

spurring us on through our short life on earth

to steep us then forever in such misery!

[tr. Musa (1971)]O blind cupidity and insane anger,

which goad us on so much in our short life,

then steep us in such grief eternally!

[tr. Mandelbaum (1980)]O blind cupidity and senseless anger,

Which so goads us in our short life here

And, in the eternal life, drenches us miserably!

[tr. Sisson (1981)]O blind desire

Of covetousness, O anger gone insane --

That goad us on through life, which is so brief,

to steep in eternal woe when life is done.

[tr. Pinsky (1994)]Oh blind cupidity and mad rage, that so spur us in this short life, and then in the eternal one cook us so evilly!

[tr. Durling (1996)]O blind desires, evil and foolish, which so goad us in our brief life, and then, in the eternal one, ruin us so bitterly!

[tr. Kline (2002)]O blind cupidity, that brew of bile

and foolishness, which bubbles our brief lives,

before it steeps us in eternal gall!

[tr. Carson (2002)]What blind cupidity, what crazy rage

impels us onwards in our little lives --

then dunks us in this stew to all eternity!

[tr. Kirkpatrick (2006)]O blind covetousness, insensate wrath,

which in this brief life goad us on and then,

in the eternal, steep us in such misery!

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]O greedy blindness and rage, insane and senseless,

Spurring us on in this, our so short life,

Then immolating us forever and ever!

[tr. Raffel (2010)]

And who can suffer injury by just taxation, impartial laws and the application of the Jeffersonian doctrine of equal rights to all and special privileges to none? Only those whose accumulations are stained with dishonesty and whose immoral methods have given them a distorted view of business, society and government. Accumulating by conscious frauds more money than they can use upon themselves, wisely distribute or safely leave to their children, these denounce as public enemies all who question their methods or throw a light upon their crimes.

William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925) American lawyer, statesman, politician, orator

Speech, Madison Square Garden, New York (1906-08-30)

(Source)

Plato said that virtue has no master. If a person does not honor this principle and rejoice in it, but is purchasable for money, he creates many masters for himself.

Apollonius of Tyana (c. AD 15-100) Greek philosopher and religious leader [Ἀπολλώνιος]

Letters from Apollonius of Tyana, ep. 15, Letter to Euphrates [tr. Jones (2006)]

(Source)

The reference to Plato's Republic, X 617 E.

Every time you get a censor, you get a fool, and worse yet a knave, pretending to be a guardian of morality, while acting as a guardian of class greed.

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) American writer, journalist, activist, politician

Money Writes!, ch. 22 “The Bookleggers” (1927)

(Source)

Self-quoted in "Poor Me and Pure Boston," The Nation (1927-06-29)

If you make money your god, it will plague you like the devil.

(Other Authors and Sources)

English proverb

Sometimes "'twill plague you".

An anonymous proverb, recorded in Thomas Fielding, ed., Select Proverbs of All Nations (1824). Thomas Fielding was the pseudonym of John Wade (1788-1875), a British journalist and author.

Though Fielding was only a compiler of proverbs and aphorisms, the quotation then shows up in a variety of collections later in the 19th Century actually cited to "Fielding," e.g., H. Southgate, ed., Many Thoughts of Many Minds (1862); John Camden Hotten, ed. The Golden Treasury of Thought (1873); Edward Parsons Day, ed., Day's Collacon: an Encyclopaedia of Prose Quotations (1884).

In relatively short order, this "Fielding" then became conflated with the more famous English writer Henry Fielding (1707-1754), to whom this quotation is often credited.

Gold and silver are the gods you adore

In what are you different from the idolater,

save that he worships one, and you a score?[Fatto v’avete dio d’oro e d’argento;

e che altro è da voi a l’idolatre,

se non ch’elli uno, e voi ne orate cento?]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 1 “Inferno,” Canto 19, l. 112ff (19.112-114) [Dante] (1309) [tr. Ciardi (1954)]

(Source)

Chiding the damned shade of Pope Nicholas III (reigned 1280-1303), who was infamous for his corruption, extorting lands for the Church from nobles before giving his blessing, taking bribes, and selling holy offices (simonism); the last has landed him in the Eighth Circle, third Bolgia, with the other simoniacs.

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:But you of silver and gold have made

Your God: What differs your Idolatry

From that of others, but that they did one

Alone, and you a hundred Gods adore.

[tr. Rogers (1782), l. 109ff]Go, seek your Saviour in the delved mine.

And bid the Idolater the palm resign;

Thine is a Legion, his a single God!

[tr. Boyd (1802), st. 19]Of gold and silver ye have made your god,

Diff’ring wherein from the idolater,

But he that worships one, a hundred ye?

[tr. Cary (1814)]Silver and gold ye make your god: what more

Divides the brute idolater and you,

Save that he one, a hundred ye adore?

[tr. Dayman (1843)]Ye have made you a god of gold and silver; and wherein do ye differ from the idolater, save that he worships one, and ye a hundred?

[tr. Carlyle (1849)]Of gold and silver you have made your god,

Idols of yours and others to recount,

Theirs to one, to a hundred yours amount.

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]Or gold and silver ye your gods have made;

And what is 'twist th' idolater and you,

But he to one -- ye to a hundred pray.

[tr. Johnston (1867)]Ye have made yourselves a god of gold and silver;

And from the idolater how differ ye,

Save that he one, and ye a hundred worship?

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]Ye have made a god of gold and silver, and what else is there between you and the idolater save that he worships one, and you a hundred.

[tr. Butler (1885)]Ye've made your God of silver and of gold.

Ye from idolaters what line withdraws.

Save they sin once, and ye a hundredfold?

[tr. Minchin (1885)]Ye have made you a god of gold and silver: and what difference is there between you and the idolater save that he worships one and ye a hundred?

[tr. Norton (1892)]A god ye have made yourselves of gold and silver,

And from idolaters what else divides you,

Save that they pray to one and you a hundred?

[tr. Griffith (1908)]You have made you a god of gold and silver, and what is there between you and teh idolaters but that they worship one and you a hundred?

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]A God of silver and gold ye have made to adore;

And how do ye differ from the idolater

Sav e that he worships one, and ye five-score?

[tr. Binyon (1943)]You deify silver and gold; how are you sundered

In any fashion from the idolater,

Save that he serves one god and you an hundred?

[tr. Sayers (1949)]You have made you a god of gold and silver; and wherein do you differ from the idolaters, save that they worship one, and you a hundred?

[tr. Singleton (1970)]You have built yourselves a God of gold and silver!

How do you differ from the idolater,

except he worships one, you worship hundreds?

[tr. Musa (1971)]You’ve made yourselves a god of gold and silver;

how are you different from idolaters,

save that they worship one and you a hundred?

[tr. Mandelbaum (1980)]You have made a god of gold and silver:

And how do you differ from an idolater,

Except that he prays to one, and you to a hundred?

[tr. Sisson (1981)]You made a god of gold and silver: wherein

Is it you differ from the idolatrous --

Save that you worship a hundred, they but one?

[tr. Pinsky (1994), l. 105ff]You have made gold and silver your god; and what difference is there between you and the idol-worshipper, except that he prays to one, and you to a hundred?

[tr. Durling (1996)]You have made a god for yourselves of gold and silver, and how do you differ from the idolaters, except that he worships one image and you a hundred?

[tr. Kline (2002)]Silver and gold you have made your god. And what’s

the odds -- you and some idol-worshipper?

He prays to one, you to a gilded hundred.

[tr. Kirkpatrick (2006)]You have wrought yourselves a god of gold and silver.

How then do you differ from those who worship idols

except they worship one and you a hundred?

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]The god you made for yourself is silver and gold --

And where are you different, you and worshippers

Of idols? They have one, and you a hundred.

[tr. Raffel (2010)]You thieves reigned,

Making a God of gold and silver. Room

Does not exist between the idolaters

And you, except they worship one, and you

A hundred.

[tr. James (2013)]

For what is there more hideous than avarice, more brutal than lust, more contemptible than cowardice, more base than stupidity and folly? Well, then, are we to call those persons unhappy, who are conspicuous for one or more of these, on account of some injuries, or disgraces, or sufferings to which they are exposed, or on account of the moral baseness of their sins?

[Quid enim foedius auaritia, quid immanius libidine, quid contemptius timiditate, quid abiectius tarditate et stultitia dici potest? Quid ergo? Eos qui singulis uitiis excellunt aut etiam pluribus, propter damna aut detrimenta aut cruciatus aliquos miseros esse dicimus, an propter uim turpitudinemque uitiorum?]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Legibus [On the Laws], Book 1, ch. 19 / sec. 51 (1.19/1.51) [Marcus] (c. 51 BC) [tr. Barham/Yonge (1878)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For what is there more hideous than avarice, more ferocious than lust, more contemptible than cowardice, more base than stupidity and folly? Well, therefore, may we style unhappy, those persons in whom any one of these vices is conspicuous, not on account of the disgraces or losses to which they are exposed, but on account of the moral baseness of their sins.

[tr. Barham (1842)]For what can be thought of that is more loathsome than greed, what more inhuman than lust, what more contemptible than cowardice, what more degraded than stupidity and folly? Well, then, shall we say that those who are sunk deepest in a single vice, or in several, are wretched on account of any penalties or losses or tortures which they incur, or on account of the base nature of the vices themselves?

[tr. Keyes (1928)]What can be called more revolting than greed, more bestial than lust, more despicable than cowardice, more abject than dullness and stupidity? What then? Take those people who are conspicuous for one (or more than one) vice. Do we call them wretched because of the losses or damages or pain they suffer, or because of the power and ugliness of their vices?

[tr. Rudd (1998)]What is uglier than greed, what is more horrible than lust, what is more contemptible than cowardice, what is lower than sloth and stupidity? What then? People who are remarkable for single vices or even for several -- do we call them wretched because of material losses or torture, or because of the great dishonor from the vices themselves?

[tr. Zetzel (1999)]What could be called fouler than avarice, what more monstrous than lust, what more scorned than cowardice, what more despicable than dullness and foolishness? What then? Do we say about those who are conspicuous for their individual vices, or even many vices, that they are wretched because of losses or damages or tortures, or because of the significance and the disgrace of their vices?

[tr. Fott (2013)]

‘Tis unbecoming not to shed a tear

Over the wretched; he too is devoid

Of virtue, who abounds in wealth, yet scruples

Thro’ sordid avarice to relieve their wants.Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Antiope [Αντιοπη], frag. (c. 410 BC) [tr. Wodhall (1809)]

(Source)

Barnes frag. 62, Musgrave frag. 40.

It is supposed to be true that those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it. I don’t believe knowing can save us. What is constant in history is greed and foolishness and a love of blood, and this is a thing that even God — who knows all that can be known — seems powerless to change.

A conservative is a man who has plenty of money and doesn’t see any reason why he shouldn’t always have plenty of money.

Will Rogers (1879-1935) American humorist

Column (1933-03-26), “Weekly Article: We’re Off to a Flying Start”

(Source)

Collected in Steven Grager, ed., Will Rogers' Weekly Articles, Vol. 6 "The Roosevelt Years, 1933-1935" (2011 ed.). Also reprinted in abbreviated format, in Donald Day, ed., The Autobiography of Will Rogers (1949).

Fell lust of gold! abhorred, accurst!

What will not men to slake such thirst?[Quid non mortalia pectora cogis,

Auri sacra fames?]Virgil (70-19 BC) Roman poet [b. Publius Vergilius Maro; also Vergil]

The Aeneid [Ænē̆is], Book 3, l. 56ff (3.56-57) [Aeneas] (29-19 BC) [tr. Conington (1866)]

(Source)

Regarding the murder of Polydorus.

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:Dire thirst of gold, what dost not thou constrain

In mortall breasts!

[tr. Ogilby (1649)]O sacred hunger of pernicious gold!

What bands of faith can impious lucre hold?

[tr. Dryden (1697)]Cursed thirst of gold, to what dost thou not drive the hearts of men?

[tr. Davidson/Buckley (1854)]Cursèd thirst for gold,

What crimes dost thou not prompt in mortal breasts!

[tr. Cranch (1872), ll. 70-71]Accursed thirst for gold! what dost thou not compel mortals to do?

[Source (1882)]O accursed hunger of gold, to what dost thou not compel human hearts!

[tr. Mackail (1885)]O thou gold-hunger cursed, and whither driv'st thou not

The hearts of men?

[tr. Morris (1900)]Curst greed of gold, what crimes thy tyrant power attest!

[tr. Taylor (1907), st. 8, l. 72]O, whither at thy will,

curst greed of gold, may mortal hearts be driven?

[tr. Williams (1910)]To what crime do you not drive the hearts of men, O accursed hunger for gold?

[tr. Fairclough (1916)]There is nothing

To which men are not driven by that hunger.

[tr. Humphries (1951)]What lengths is the heart of man driven to

By this cursed craving for gold!

[tr. Day Lewis (1952)]To what, accursed lust for gold, do you

not drive the hearts of men?

[tr. Mandelbaum (1971), ll. 73-74]To what extremes

Will you not drive the hearts of men, accurst

Hunger for gold!

[tr. Fitzgerald (1981), ll. 79-81]Greed for gold is a curse. There is nothing to which it does not drive the minds of men.

[tr. West (1990)]Accursed hunger for gold, to what do you

not drive human hearts!

[tr. Kline (2002)]To what extremes won't you compel our hearts,

you accursed lust for gold?

[tr. Fagles (2006)]Unholy lust for gold! Is there nothing men won't do for you?

[tr. Bartsch (2021)]

It is in vain to Say that Democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious or less avaricious than Aristocracy or Monarchy. It is not true in Fact and no where appears in history. Those Passions are the same in all Men under all forms of Simple Government, and when unchecked, produce the same Effects of Fraud Violence and Cruelty. When clear Prospects are opened before Vanity, Pride, Avarice or Ambition, for their easy gratification, it is hard for the most considerate Phylosophers and the most conscientious Moralists to resist the temptation. Individuals have conquered themselves, Nations and large Bodies of Men, never.

John Adams (1735-1826) American lawyer, Founding Father, statesman, US President (1797-1801)

Letter to John Taylor (17 Dec 1814)

(Source)

For the old notions of civil liberty and social order did not benefit the masses of the people. Wealth increased, without relieving their wants. The progress of knowledge left them in abject ignorance. Religion flourished, but failed to reach them. Society, whose laws were made by the upper class alone, announced that the best thing for the poor is not to be born, and the next best, to die in childhood, and suffered them to live in misery and crime and pain. As surely as the long reign of the rich has been employed in promoting the accumulation of wealth, the advent of the poor to power will be followed by schemes for diffusing it. Seeing how little was done by the wisdom of former times for education and public health, for insurance, association, and savings, for the protection of labour against the law of self-interest, and how much has been accomplished in this generation, there is reason in the fixed belief that a great change was needed, and that democracy has not striven in vain.

John Dalberg, Lord Acton (1834-1902) British historian, politician, writer

“Review of Sir Erskine May’s Democracy in Europe,” The Quarterly Review (1878-01)

(Source)

Preacher preaching love like vengeance

Preaching love like hate

Calling for large donations

Promising estates

Rolling lawns and angel bands

Behind the pearly gates

You know he will have his in this life

But yours will have to wait

He’s immaculately tax freeJoni Mitchell (b. 1943) Canadian singer-songwriter and painter [b. Roberta Joan Anderson]

“Tax Free” Joni Mitchell (1985)

(Source)

Few men, indeed, are so mad that they do not know when they are doing wrong. But so avid is their pursuit of goods that wrongdoing has become an element of all they do. To protest that fact is idle. Our politics, our business — little and big, our professions, our labor, are smitten in every facet with a corruption occasioned by reckless determination to make not just a reasonable profit but all the profit that can be wrung from every enterprise. Our commonest man, emulating his superiors, forges ahead with a brick on the safety valve of his conscience. Think over your morning paper in that light.

Large banks are essentially large children in search of candy, except the candy is profits. The only thing preventing them from grabbing all the candy and making themselves sick are laws and regulations. We cannot rely on them to act morally. It’s not their nature.

Thornton McEnery (contemp.) American business journalist

“Jeffrey Epstein Should Be the Literal End of Deutshe Bank USA,” Above the Law (11 Jul 2019)

(Source)

We are all born brave, trusting and greedy, and most of us manage to remain greedy.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Second Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 9 (1966)

(Source)

There is always someone ready to be lured to ruin by hope of gain.

[ἀλλ᾽ ὑπ᾽ ἐλπίδων ἄνδρας τὸ κέρδος πολλάκις διώλεσεν.]

Sophocles (496-406 BC) Greek tragic playwright

Antigone, l. 221ff [Creon] (441 BC) [tr. Watling (1947)]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:

- "But backed by hope, lucre has ruined many." [tr. Donaldson (1848)]

- "Yet hope of gain hath lured men to their ruin oftentimes." [tr. Storr (1859)]

- "But hope of gain full oft ere now hath been the ruin of men." [tr. Campbell (1873)]

- "Yet by just the hope of it, money has many times corrupted men." [tr. Jebb (1891)]

- "Yet lucre hath oft ruined men through their hopes." [tr. Jebb (1917)]

- "Yet money talks, and the wisest have sometimes been known to count a few coins too many." [tr. Fitts/Fitzgerald (1939)]

- "But often we have known men to be ruined by the hope of profit." [tr. Wyckoff (1954)]

- "But love of gain has often lured a man to his destruction." [tr. Kitto (1962)]

- "But all too often the mere hope of money has ruined many men." [tr. Fagles (1982)]

- "But hope -- and bribery -- often have led men to destruction." [tr. Woodruff (2001)]

- "But profit with its hopes often destroys men." [tr. Tyrell/Bennett (2002)] https://diotima-doctafemina.org/translations/greek/sophocles-antigone/#post-1273:~:text=But%20profit,with%20its%20hopes%20often%20destroys%20men.

- "Yet there are men who the mere hope of winning has killed them." [tr. Theodoridis (2004)]

- "And yet men have often been destroyed because they hoped to profit in some way." [tr. Johnston (2005)]

- "But often profit has destroyed men through their hopes." [tr. Thomas (2005)]

- "But the profit-motive has destroyed many people in their hope for gain." [tr. @sentantiq (2018)]

If all men were rich, all men would be poor.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

Mark Twain’s Noteook (1935 ed) [ed. Paine]

(Source)

CREON: Prophecies? All your tribe wants is to make money.

TIRESIAS: And what about tyrants? Filthy lucre is all you want![Κρέων: τὸ μαντικὸν γὰρ πᾶν φιλάργυρον γένος.

Τειρεσίας: τὸ δ᾽ ἐκ τυράννων αἰσχροκέρδειαν φιλεῖ.]Sophocles (496-406 BC) Greek tragic playwright

Antigone, l. 1055ff (441 BC) [tr. Woodruff (2001)]

(Source)

Argument between Creon, the king, and Teiresias, his seer. Original Greek. Alternate translations:KREON: The race of seers is wholly given to pelf.

TEIRESIAS: The tyrant-race is given to filthy lucre.

[tr. Donaldson (1848)]CREON: Prophets are all a money-getting tribe.

TEIRESIAS: And kings are all a lucre-loving race.

[tr. Campbell (1873)]CREON: Desire of money is the prophet's plague.

TIRESIAS: And ill-sought lucre is the curse of kings.

[tr. Storr (1859)]CREON: Yes, for the prophet-clan was ever fond of money.

TEIRESIAS: And the race sprung from tyrants loves shameful gain.

[tr. Jebb (1891)]CREON: Your prophetic race are lovers all of gold.

TIRESIAS: Tyrants are so, howe'er illgotten.

[tr. Werner (1892)]CREON: Well, the prophet-tribe was ever fond of money.

TEIRESIAS: And the race bred of tyrants loves base gain.

[tr. Jebb (1917)]CREON: The generation of prophets has always loved gold.

TEIRESIAS: The generation of kings has always loved brass.

[tr. Fitts/Fitzgerald (1939)]CREON: I say all prophets seek their own advantage.

TEIRESIAS: All kings, I say, seek gain unrighteously.

[tr. Watling (1947)]CREON: Well, the whole crew of seers are money-mad.

TEIRESIAS: And the whole tribe of tyrants grab at gain.

[tr. Wyckoff (1954)]CREON: Prophets have always been too fond of gold.

TEIRESIAS: And tyrants, of the shameful use of power.

[tr. Kitto (1962)]CREON: You and the whole breed of seers are mad for money!

TIRESIAS: And the whole race of tyrants lusts for filthy gain.

[tr. Fagles (1982), l. 1171ff]CREON: Yes, for the whole family of prophets is philos to silver.

TIRESIAS: And the family of absolute rulers holds disgraceful profits as philoi.

[tr. Tyrell/Bennett (2002)]CREON: The whole race of prophets loves money.

TEIRESIAS: And the kings love their shameful profits.

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]CREON: The tribe of prophets --

all of them -- are fond of money.

TEIRESIAS: And kings?

Their tribe loves to benefit dishonestly.

[tr. Johnston (2005), l. 1180ff]TEIRESIAS: The race of tyrants loves shameful profit.

[tr. @senstantiq (2018)]

As soon as riches came to be held in honour, when glory, dominion, and power followed in their train, virtue began to lose its lustre, poverty to be considered a disgrace, blamelessness to be termed malevolence. Therefore as the result of riches, luxury and greed, united with insolence, took possession of our young manhood. They pillaged, squandered; set little value on their own, coveted the goods of others; they disregarded modesty, chastity, everything human and divine; in short, they were utterly thoughtless and reckless.

[Postquam divitiae honori esse coepere et eas gloria, imperium, potentia sequebatur, hebescere virtus, paupertas probro haberi, innocentia pro malivolentia duci coepit. Igitur ex divitiis iuventutem luxuria atque avaritia cum superbia invasere; rapere, consumere, sua parvi pendere, aliena cupere, pudorem, pudicitiam, divina atque humana promiscua, nihil pensi neque moderati habere.]

Sallust (c. 86-35 BC) Roman historian and politician [Gaius Sallustius Crispus]

Bellum Catilinae [The War of Cateline; The Conspiracy of Catiline], ch. 12, sent. 1-2 [tr. Rolfe (1931)]

(Source)

Original Latin. Alt. trans.:

- "Riches became the epidemic passion; and where honours, imperial sway, and power, followed in their train, virtue lost her influence, poverty was deemed the meanest disgrace, and innocence was thought to be no better than a mark for malignity of heart. In this manner riches engendered luxury, avarice, and pride; and by those vices the Roman youth were enslaved. Rapacity and profusion went on increasing; regardless of their own property, and eager to seize that of their neighbours, all rushed forward without shame or remorse, confounding every thing sacred and profane, and scorning the restraint of moderation and justice." [tr. Murphy (1807)]

- "When riches began to be held in high esteem, and attended with glory, honour, and power, virtue languished, poverty was deemed a reproach, and innocence passed for ill-nature. And thus luxury, avarice, and pride, all springing from riches, enslaved the Roman youth; they wantoned in rapine and prodigality; undervalued their own, and coveted what belonged to others; trampled on modesty, friendship, and continence; confounded things divine and human; and threw off all manner of consideration and restraint." [tr. Rose (1831)]

- "After that riches began to be an honour and glory, and command and power followed them, virtue began to languish, poverty to be accounted matter of reproach, and innocence to be considered as malignity. Therefore from riches, luxury and avarice with pride came in upon our youth. They ravaged and wasted every thing, their own property they valued at a trifle, that of other persons they coveted, and had not the least care for, or moderation in, shame, modesty, sacred or profane things, which were all the same to them." [Source (1841)]

- "When wealth was once considered an honor, and glory, authority, and power attended on it, virtue lost her influence, poverty was thought a disgrace, and a life of innocence was regarded as a life of ill-nature. From the influence of riches, accordingly, luxury, avarice, and pride prevailed among the youth; they grew at once rapacious and prodigal; they undervalued what was their own, and coveted what was another’s; they set at naught modesty and continence; they lost all distinction between sacred and profane, and threw off all consideration and self-restraint." [tr. Watson (1867)]

- "Riches became a means of distinction and glory, power and influence followed their possession. As a result the edge of virtue was dulled, poverty was accounted a disgrace, and uprightness a kind of ill-nature. Riches made the youth prey to luxury, avarice, and pride: at once grasping and prodigal, they valued lightly their own property, while the coveted that of others; all modesty and purity, alike things human and things divine, everything, in short, was despised and disregarded." [tr. Pollard (1882)]

- "After riches began to be a source of honour and to be attended by glory, command and power, prowess began to dull, poverty to be considered a disgrace and blamelessness to be regarded as malice. In the wake of riches, therefore, young men were attacked by luxury and avarice along with haughtiness; they seized, they squandered; they placed little weight on their own property and desired that of others; they considered propriety and unchastity, divine and human matters, as indistinguishable, and nothing as worth weight or restraint." [tr. Woodman (2007)]

Avarice, on the other hand, implies a zeal for money, an object for which no philosopher ever yearned. Tainting the body and mind of the strong, it weakens them as by some deadly poison; it is always boundless, always insatiable; plenty and want alike fail to lessen it.

[Avaritia pecuniae studium habet, quam nemo sapiens concupivit; ea quasi venenis malis imbuta corpus animumque virilem effeminat, semper infinita, insatiabilis est, neque copia neque inopia minuitur.]

Sallust (c. 86-35 BC) Roman historian and politician [Gaius Sallustius Crispus]

Bellum Catilinae [The War of Cateline; The Conspiracy of Catiline], ch. 11, sent. 3 [tr. Pollard (1882)]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- "Avarice, on the other hand, aims at an accumulation of riches; a passion unknown in liberal minds. It may be called a compound of poisonous ingredeients; it has power to enervate the body, and debauch the best understanding; always unbounded; never satisfied; in plenty and in want equally craving and rapacious." [tr. Murphy (1807)]

- "Avarice has money for its object, which no wise man ever coveted. This vice, as if impregnated with deadly poison, enervated both soul and body; is always boundless and insatiable; nor are its cravings lessened by plenty or want." [tr. Rose (1831)]

- "Avarice has a longing for money, which no wise man ever desired. This passion, as if it were imbued with deadly poisons, enervates the body and mind of man. It is always boundless, insatiable, is neither diminished by plenty nor want." [Source (1841)]

- "But avarice has merely money for its object, which no wise man has ever immoderately desired. It is a vice which, as if imbued with deadly poison, enervates whatever is manly in body or mind. It is always unbounded and insatiable, and is abated neither by abundance nor by want." [tr. Watson (1867)]

- "Avarice implies a desire for money, which no wise man covets; steeped as it were with noxious poisons, it renders the most manly body and soul effeminate; it is ever unbounded and insatiable, nor can either plenty or want make it less." [tr. Rolfe (1931)]

- "Avarice involves an enthusiasm for money (which no wise man has ever desired): as if saturated with a harmful poison, it feminizes the manly body and mind, knows neither limit nor surfeit, and lessened by neither sufficiency nor insufficiency." [tr. Woodman (2007)]

Their frail human nature was subjected to a strain greater than it was made for; the fires of greed had been lighted in their hearts, and fanned to a white heat that melted every principle and every law.

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) American writer, journalist, activist, politician

Oil!, ch. 2 (1927)

(Source)

In this decline of all public virtue, ambition, and not avarice, was the passion that first possessed the minds of men; and this was natural. Ambition is a vice that borders on the confines of virtue; it implies a love of glory, of power, and pre-eminence; and these are objects that glitter alike in the eyes of the man of honour, and the most unprincipled: but the former pursues them by fair and honourable means, while the latter, who finds within himself no resources of talent, depends altogether upon intrigue and fallacy for his success.

[Sed primo magis ambitio quam avaritia animos hominum exercebat, quod tamen vitium propius virtutem erat. Nam gloriam, honorem, imperium bonus et ignavus aeque sibi exoptant; sed ille vera via nititur, huic quia bonae artes desunt, dolis atque fallaciis contendit.]

Sallust (c. 86-35 BC) Roman historian and politician [Gaius Sallustius Crispus]

Bellum Catilinae [The War of Cateline], ch. 11, sent. 1-2 [tr. Murphy (1807)]

(Source)

Also known as Catilinae Coniuratio [The Conspiracy of Cateline]. (Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:At first, indeed, the minds of men were less influenced by avarice than ambition, a vice which has some affinity to virtue; for the desire of glory, power, and preferment is common to the worthy and the worthless; with this difference, that the one pursues them by direct means; the other, being void of merit, has recourse to fraud and subtlety.

[tr. Rose (1831)]But at first ambition more than avarice influenced the minds of the Romans. Which vice however was the nearer to virtue. For glory, honour, command, the good and slothful equally wish for themselves. But the former strives by the right course; to the latter because good qualities are wanting, he works by tricks and deceits.

[Source (1841)]At first, however, it was ambition, rather than avarice, that influenced the minds of men; a vice which approaches nearer to virtue than the other. For of glory, honor, and power, the worthy is as desirous as the worthless; but the one pursues them by just methods; the other, being destitute of honorable qualities, works with fraud and deceit.

[tr. Watson (1867)]At first it was not so much avarice as ambition which spurred men's minds, a vice, indeed, but one akin to virtue. Glory, distinction, and power in the state are equally desired by good and bad, though the first strives to reach his goal by the path of honor, the second, in the lack of honest arts, uses the weapons of falsehood and deceit.

[tr. Pollard (1882)]But at first men’s souls were actuated less by avarice than by ambitions -- a fault, it is true, but not so far removed from virtue; for the noble and the base alike long for glory, honour, and power, but the former mount by the true path, whereas the latter, being destitute of noble qualities, rely upon craft and deception.

[tr. Rolfe (1931)]At first people's minds were taxed less by avarice than by ambition, which, though a fault, was nevertheless closer to prowess: for the good man and the base man have a similar personal craving for glory, honour, and command, but the former strives along the truth path, whereas the latter, because he lacks good qualities, presses forward by cunning and falsity.

[tr. Woodman (2007)]

Hence the lust for money first, then for power, grew upon them; these were, I may say, the root of all evils. For avarice destroyed honour, integrity, and all the other noble qualities; taught in their place insolence, cruelty, to neglect the gods, to set a price on everything. Ambition drove many men to become false; to have one thought locked in the breast, another ready on the tongue; to value friendships and enmities not on their merits but by the standard of self-interest, and to show a good front rather than a good heart. At first these vices grew slowly, from time to time they were punished; finally, when the disease had spread like a deadly plague, the state was changed and a government second to none in equity and excellence became cruel and intolerable.

[Igitur primo imperi, deinde pecuniae cupido crevit: ea quasi materies omnium malorum fuere. Namque avaritia fidem, probitatem ceterasque artis bonas subvortit; pro his superbiam, crudelitatem, deos neglegere, omnia venalia habere edocuit. Ambitio multos mortalis falsos fieri subegit, aliud clausum in pectore, aliud in lingua promptum habere, amicitias inimicitiasque non ex re, sed ex commodo aestumare magisque voltum quam ingenium bonum habere. Haec primo paulatim crescere, interdum vindicari; post, ubi contagio quasi pestilentia invasit, civitas inmutata, imperium ex iustissumo atque optumo crudele intolerandumque factum.]

Sallust (c. 86-35 BC) Roman historian and politician [Gaius Sallustius Crispus]

Bellum Catilinae [The War of Catiline; The Conspiracy of Catiline], ch. 10, sent. 3-6 [tr. Rolfe (1931)]

(Source)

Discussing the corruption of Rome in the years after the final defeat of Carthage.