They will teach us to quarrel about God, as Catholics and Protestants do on the Nez Percé Reservation [in Idaho] and at other places. We do not want to do that. We may quarrel with men sometimes about things on earth, but we never quarrel about the Great Spirit. We do not want to learn that.

Chief Joseph (1840-1904) Leader of the Wallowa band of the Nez Percé [Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it]

Statement (1873-03-27) to T. B. Odeneal

(Source)

When asked by US government commissioners about allowing schools and Christian churches on a proposed Wallowa Valley Nez Percé reservation.

A slightly shorter version of this quotation is prominently displayed at the visitors center of the Crazy Horse Monument, South Dakota.

Quotations about:

argument

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

A good Cause doth not want any Bitterness to support it, as a bad one cannot subsist without it. It is indeed observable, that an Author is scurrilous in proportion as he is dull; and seems rather to be in a Passion, because he cannot find out what to say for his own Opinion, than because he has discovered any pernicious Absurdities in that of his Antagonists.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Essay (1716-06-29), The Freeholder, No. 55

(Source)

The difficult part of an argument is not to defend one’s opinion, but rather to know it.

André Maurois (1885-1967) French author [b. Émile Salomon Wilhelm Herzog]

Conversation, “Action in Conversation” (1930)

(Source)

LADY BRACKNELL: I dislike arguments of any kind. They are always vulgar, and often convincing.

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) Irish poet, wit, dramatist

The Importance of Being Ernest, Act 3 (1895)

(Source)

Arguments are like fire-arms, which a man may keep at home but should not carry about with him.

Samuel Butler (1835-1902) English novelist, satirist, scholar

Note-books, ch. 10 “The Position of a Homo Unius Libri,” “The Art of Propagating Opinion” [ed. Jones (1912)]

(Source)

There is this disadvantage to be endured in reading books by members of some party or faction, that they do not always give us the truth. Facts are distorted, opposing points of view are not stated with sufficient force or with complete accuracy; and the most longsuffering reader must tire at last of such a great number of harsh and insulting terms used against one another by these earnest men, who make a personal quarrel out of a doctrinal point or a disputed fact. The peculiar thing about these works is that they deserve neither the prodigious vogue they enjoy for a while nor the profound neglect into which they lapse when, passions and divisions having died down, they become like last year’s almanacs.

[L’on a cette incommodité à essuyer dans la lecture des livres faits par des gens de parti et de cabale, que l’on n’y voit pas toujours la vérité. Les faits y sont déguisés, les raisons réciproques n’y sont point rapportées dans toute leur force, ni avec une entière exactitude; et, ce qui use la plus longue patience, il faut lire un grand nombre de termes durs et injurieux que se disent des hommes graves, qui d’un point de doctrine ou d’un fait contesté se font une querelle personnelle. Ces ouvrages ont cela de particulier qu’ils ne méritent ni le cours prodigieux qu’ils ont pendant un certain temps, ni le profond oubli où ils tombent lorsque, le feu et la division venant à s’éteindre, ils deviennent des almanachs de l’autre année.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 1 “Of Works of the Mind [Des Ouvrages de l’Esprit],” § 58 (1.58) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

Some translators suggests this references polemical writings between the Jesuits and Jansenists.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:We have this disadvantage in reading Books written by Men of Party and Cabal: We seldom meet with the Truth in 'em; Actions are there disguised, the reasons of both sides are not alledg'd with all their force, nor with an entire exactness. He who has the greatest patience must read abundance of hard, injurious reflexions on the gravest men, with whom the Writer has some personal quarrel about a point of Doctrine, or matter of Controversie. These Books are particular in this, that they deserve not the prodigious Sale they find at their first appearance, nor the profound Oblivion that attends 'em after∣wards: When the fury and division of these Authors cease, they are forgotten, like an Almanack out of date.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]We have this Inconveniency in reading Books written by Men of Party and Cabal, we seldom meet Truth in them; Actions are there disguis'd, the Reasons of both sides not alledg'd with all their force, nor with an entire exactness. He who has the greatest Patience, must read abundance of hard and scurrilous Reflections on the gravest Men, who make a personal Quarrel about a Point of Doctrine, or Matter of Controversy. These Books are particular in this, that they deserve not the prodigious Sale they find at their first appearance, nor the profound Oblivion which attends 'em afterwards. When the Fury and Division of Parties cease, they are forgotten like Almanacks out of date.

[Curll ed. (1713)]This is the certain disadvantage of reading Books written by Men of Party and Cabal, Truth is not in them; Actions are disguised, the Reasons of both sides are not alledged with all their force, nor with an entire exactness. And, what no patience can bear, he must read abundance of scurrilous Reflections tost to and fro by grave Men, making a personal Quarrel about a Point of Doctrine, or controverted Fact. These Books are particular in this, that they deserve not the prodigious Sale they find at their first appearance, nor the profound Oblivion that attends them afterwards: When the Ebullitions of Parties subside, they are forgotten like an Almanack out of date.

[Browne ed. (1752)]The disadvantage of reading books written by people belonging to a certain party or a certain set is that they do not always contain the truth. Facts are disguised, the arguments on both sides are not brought forward in all their strength, nor are they quite accurate; and what wears out the greatest patience is that we must read a large number of harsh and scurrilous reflections, tossed to and fro by serious-minded men, who consider themselves personally insulted when any point of doctrine or any doubtful matter is controverted. Such works possess this peculiarity, that they neither deserve the prodigious success they have for a certain time, nor the profound oblivion into which they fall afterwards, when the rage and contention have ceased, and they become like almanacks out of date.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

You can see how infinitely laborious and fruitless it would be to try to refute every objection they offer, when they have resolved never to think before they speak provided that somehow or other they contradict our arguments.

[Quorum dicta contraria si totiens uelimus refellere, quotiens obnixa fronte statuerint non cogitare quid dicant, dum quocumque modo nostris disputationibus contradicant, quam sit infinitum et aerumnosum et infructuosum uides.]

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

City of God [De Civitate Dei], Book 2, ch. 1 (2.1) (AD 412-416) [tr. Bettenson (1972)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:If we should bind ourselves to give an answer to every contradiction that their impudence will thrust forth (how falsely they care not, for they do but make a show of opposition into our assertions), you see what a trouble it would be, how endless, and how fruitless.

[tr. Healey (1610)]Now, if we were to propose to confute their objections as often as they with brazen face chose to disregard our arguments, and so often as they could by any means contradict our statements, you see how endless, and fruitless, and painful a task we should be undertaking.

[tr. Dods (1871)]You can easily see what an endless, wearisome, and fruitless task it would be, if I were to refute all the unconsidered objections of people who pig-headedly contradict everything I say.

[tr. Zema/Walsh (1950)]If we were bound to refute their objections every time they make their bull-headed resolve not to consider the meaning of their words as long as they deny our arguments, no matter how, you see how endless and wearisome and unprofitable it would be.

[tr. McCracken (Loeb) (1957)]If we resolved to refute their contrary arguments as often as they resolve obstinately to contradict our reasoning in whatever way they can, without considering the truth of what they say, you see what an infinite and toilsome and fruitless task we should have.

[tr. Dyson (1998)]So you see how endlessly futile and fruitless it would be if we wanted to refute their objections every time they obstinately resolved not to think through what they say but merely to speak, just so long as they contradict our arguments in any way they can.

[tr. Babcock (2012)]

A bitter-tongued parent cannot teach respect for facts. Truth for its own sake can be a deadly weapon in family relations. Truth without compassion can destroy love. Some parents try too hard to prove exactly how, where and why they have been right. This approach will bring bitterness and disappointment. When attitudes are hostile, facts are unconvincing.

Haim Ginott (1922-1973) Israeli-American school teacher, child psychologist, psychotherapist [b. Haim Ginzburg]

Between Parent and Teenager, ch. 2 “Rebellion and Response” (1969)

(Source)

Sometimes mis-cited to the earlier Between Parent and Child (1965).

For most men (till by losing rendered sager)

Will back their own opinions by a wager.

It is astonishing how articulate one can become when alone and raving at a radio. Arguments and counter arguments, rhetoric and bombast flow from one’s lips like scurf from the hair of a bank manager.

Stephen Fry (b. 1957) British actor, writer, comedian

“Trefusis on Any Questions,” Loose Ends, BBC Radio 4 (c. 1987)

(Source)

Reprinted in Paperweight (1992)

I never diskuss politiks nor sektarianism; i beleave in letting every man fight hiz rooster hiz own way.

[I never discuss politics nor [religious] sectarianism; I believe in letting every man fight his rooster his own way.]Josh Billings (1818-1885) American humorist, aphorist [pseud. of Henry Wheeler Shaw]

Everybody’s Friend, Or; Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor, ch. 131 “Affurisms: Plum Pits (1)” (1874)

(Source)

The true spirit of conversation consists in building on another man’s observation, not overturning it.

Edward George Bulwer-Lytton (1803-1873) English novelist and politician

The Student, Vol. 2, “The New Phaedo,” Conversation 1 (1835)

(Source)

See La Bruyere.

A polite man is one who listens with interest to things he knows all about, when they are told him by a person who knows nothing about them.

Charles de Morny (1811-1865) French statesman [Charles Auguste Louis Joseph de Morny, 1st Duc de Morny]

(Attributed)

Earliest reference found here (1872).

Argument and flattery are but poor elements out of which to form a conversation.

[Widerspruch und Schmeichelei machen beide ein schlechtes Gespräch.]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) German poet, statesman, scientist

Elective Affinities [Die Wahlverwandtschaften], Part 2, ch. 4, “From Ottilie’s Journal [Aus Ottiliens Tagebuche]” (1809) [Niles ed. (1872)]

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translation:Contradiction and flattery both make bad conversation.

[tr. Hollingdale (1971)]

The delight of social relations between friends is fostered by a shared attitude to life, together with certain differences of opinion on intellectual matters, through which either one is confirmed in one’s own views, or else one gains practice and instruction through argument.

[Le plaisir de la société entre les amis se cultive par une ressemblance de goût sur ce qui regarde les moeurs, et par quelques différences d’opinions sur les sciences: par là ou l’on s’affermit dans ses sentiments, ou l’on s’exerce et l’on s’instruit par la dispute.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 5 “Of Society and Conversation [De la Société et de la Conversation],” § 61 (5.61) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:The pleasure of Society amongst Friends is cultivated by a likeness of Inclinations, as to Manners; and a difference in Opinion, as to Sciences: the one confirms and humours us in our sentiments; the other exercises and instructs us by disputation.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]The Pleasure of Society amongst Friends, is cultivated by a likeness of Inclinations, as to Manners, and by some difference in Opinion, as to Sciences: The one confirms us in our Sentiments, the other exercises and instructs us by Disputation.

[Curll ed. (1713)]The pleasure of social intercourse amongst friends is kept up by a similarity of morals and manners, and by slender differences in opinion about science; this confirms us in our sentiments, exercises our faculties or instructs us through arguments.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

By a pompous parade of words, some learned men have so managed it, that an unjust cause has often gained the victory, and reason submitted to sophistry and chicane.

[Gli uomini letterati, per pompa di parlare, fanno ben spesso che il torto vince, e che la ragione perde.]

Giovanni della Casa (1503-1556) Florentine poet, author, diplomat, bishop

Galateo: Or, A Treatise on Politeness and Delicacy of Manners [Il Galateo overo de’ costumi], ch. 29 (1558) [tr. Graves (1774)]

(Source)

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:But, we see that Learned men have suche art and cunning to persuade, and such filed wordes to serve their turne: that wrong doth carry the cause away, and Reason cannot prevaile.

[tr. Peterson (1576)]Men of letters, with their parade of high-flown language, very often make the wrong to prevail and the right to succumb.

[ed. Harbottle (1897)]We find that learned men, through their grandiose talk, very often manage to have the wrong side win and reason lose.

[tr. Eisenbichler/Bartlett (1986)]

Sharing the food is to me more important than arguing about beliefs. Jesus, according to the gospels, thought so too.

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020) English-American theoretical physicist, mathematician, futurist

“Progress in Religion,” Templeton Prize acceptance speech, Washington National Cathedral (9 May 2000)

(Source)

The arguments of tyranny are as contemptible as its force is dreadful.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) Anglo-Irish statesman, orator, philosopher

Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

(Source)

I cannot guess why it is so, but those who know the least speak the most.

[E non so io indovinare donde ciò proceda, che chi meno sa più ragioni.]

Giovanni della Casa (1503-1556) Florentine poet, author, diplomat, bishop

Galateo: Or, A Treatise on Politeness and Delicacy of Manners [Il Galateo overo de’ costumi], ch. 24 (1558) [tr. Einsenbichler/Bartlett (1986)]

(Source)

(Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:Nor can I guess at the cause, (though it is certainly fact) why he that knows the least, should always talk the most.

[tr. Graves (1774)]I cannot divine how it happens that the man who knows the least is the most argumentative.

[Source]

A clever speaker can speak on any

subject, either for or against.[ἐκ παντὸς ἄν τις πράγµατος δισσῶν λόγων

ἀγῶνα θεῖτ᾽ἄν, εἰ λέγειν εἴη σοφός.]Euripides (485?-406? BC) Greek tragic dramatist

Antiope [Αντιοπη], frag. 189 (TGF, Kannicht) [Chorus] (c. 410 BC)

(Source)

Barnes frag. 79, Musgrave 39. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:The skillful orator can either side

Maintain on every topic of debate.

[tr. Wodhall (1809)]A man could make an argument for two sides of any

matter, if he were a clever speaker.

[tr. Will (2015)]

Although we have already spoken in the First Part touching the utility of the definition of terms, it is nevertheless so important, that we cannot have it too much impressed on our minds, since we may by it clear up a number of disputes, which have as their subject often only the ambiguity of terms, which one takes in one sense, and another in another. So that some of the greatest controversies would cease in a moment, if one or the other of the disputants took care to make out precisely, and in a few words, what he understands by the terms which are the subject of dispute.

Antoine Arnauld (1612-1694) French theologian, philosopher, mathematician

Logic, or the Art of Thinking [La Logique ou l’art de penser; The Port-Royal Logic], Part 4, ch. 4 (1662) [with Pierre Nicole] [tr. Baynes (1850)]

(Source)

Alternate translation:Although we have already spoken in Part I about the usefulness of defining one's terms, this is, however, so important that we cannot bear it too much in mind, since this is how countless disputes are cleared up whose cause is often merely an ambiguity in terms that one person takes one way and another person another way. Accordingly, some very serious arguments would cease in an instant if either of the disputants took the care to indicate clearly, in a few words, the meanings of the terms that are the subject of dispute.

[tr. Buroker (1996)]

The river of truth is always splitting up into arms that reunite. Islanded between them, the inhabitants argue for a lifetime as to which is the mainstream.

Cyril Connolly (1903-1974) English intellectual, literary critic and writer.

The Unquiet Grave, Part 3 “La Clé des Chants” (1944)

(Source)

Often misquoted:Truth is a river that is always splitting up into arms that reunite. Islanded between the arms, the inhabitants argue for a lifetime as to which is the main river.

Even when you are right, it is good to make concessions: people will recognize you were right but admire your courtesy. More is lost through holding on than can be won by defeating others. One defends not truth but rudeness.

[Aun en caso de evidencia, es ingenuidad el ceder, que no se ignora la razón que tuvo y se conoce la galantería que tiene. Más se pierde con el arrimamiento que se puede ganar con el vencimiento; no es defender la verdad, sino la grosería.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 183 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:It is civil to yield, even in those things wherein we have greatest reason and certainty: for then all know, who had reason on their side: and besides the reason, Gallantry is also discovered in the procedure. There is more esteem lost, by a wilfull resistence, then there is got by carrying it by open force. For that is not so much a defending of truth, as a demonstration of Clownishness.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Even in cases of obvious certainty it is fine to yield: our reasons for holding the view cannot escape notice, our courtesy in yielding must be the more recognised. Our obstinacy loses more than our victory yields: that is not to champion truth but rather rudeness.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]Even with the proof on your side, it is well to make concession, for your reasons are known and your gentlemanliness is recognized; more is lost in contention than can be gained in consummation, for such does not defend the truth, but only exhibits bad manners.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

The vulgar ignorance of stubborn people makes them prefer contention to truth and utility. Prudent people are on the side of reason, not passion, whether because they foresaw it from the first, or because they improved their position later.

[Vulgaridad de temáticos, no reparar en la verdad, por contradecir, ni en la utilidad, por litigar. El atento siempre está de parte de la razón, no de la pasión, o anticipándose antes o mejorándose después.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 142 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:It is the custome of the head strong to regard neither truth in contradicting; nor profit in disputing. A wise man hath always reason on his side, and never falls into passion. He either prevents or retreats.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]'Tis the common failing of the obstinate that they lose the true by contradicting it, and the useful by quarrelling with it. The sage never places himself on the side of passion but espouses the cause of right, either discovering it first or improving it later.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]The vulgarity of these clowns, that they observe not the truth, because they lie, nor yet their own interest, because on the wrong side. A heedful man stands always on the side of reason, and never that of passion, either because he foresaw it from the first, or found it better afterwards.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

Many see the trees but not the forest, or bark up the wrong tree, speaking endlessly, reasoning uselessly, without getting to the heart of the matter. They go round and round, tiring themselves and us, and never get to what is important. This happens to people with confused minds who do not know how to clear away the brambles. They waste time and patience on what it would be better to leave alone, and later there is no time for what they left.

[Vanse muchos o por las ramas de un inútil discurrir, o por las hojas de una cansada verbosidad, sin topar con la sustancia del caso. Dan cien vueltas rodeando un punto, cansándose y cansando, y nunca llegan al centro de la importancia. Procede de entendimientos confusos, que no se saben desembarazar. Gastan el tiempo y la paciencia en lo que habían de dejar, y después no la hay para lo que dejaron.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 136 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:Many fetch a tedious compass of words, without ever coming to the knot of the business: they make a thousand turnings and windings, that tire themselves and others, without ever arriving at the point of importance. And that proceeds from the confusion of their understanding, which cannot clear it self. They lose time and patience in what ought to be let alone, and then they have no more to bestow upon what they have omitted.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Many lose their way either in the ramifications of useless discussion or in the brushwood of wearisome verbosity without ever realising the real matter at issue. They go over a single point a hundred times wearying themselves and others and yet never touch the all important centre of affairs. This comes from a confusion of mind from which they cannot extricate themselves. They waste time and patience on matters they should leave alone and cannot spare them afterwards for what they have left alone.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]Most roam around, in useless millings either about the edge, or in the scrub of a tiresome verbosity, without striking upon the substance of the matter, they make a hundred turns about a point, wearying themselves, and wearying others, yet never arriving at the centre of what is important,- it is the product of a scattered brain that does not know how to get itself together,- they spend time, and exhaust patience, over that which they should leave alone, and afterwards are short of both for what they did leave alone.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

In discussion it is not so much weight of authority as force of argument that should be demanded. Indeed the authority of those who profess to teach is often a positive hindrance to those who wish to learn; they cease to employ their own judgment, and take what they perceive to be the verdict of their chosen master as settling the question.

[Non enim tam auctoritatis in disputando quam rationis momenta quaerenda sunt. Quin etiam obest plerumque iis qui discere volunt auctoritas eorum qui se docere profitentur; desinunt enim suum iudicium adhibere, id habent ratum quod ab eo quem probant iudicatum vident.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Natura Deorum [On the Nature of the Gods], Book 1, ch. 5 / sec. 10 (1.10) (45 BC) [tr. Rackham (1933)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translation:For the force of reason in disputation is to be sought after rather than authority, since the authority of the teacher is often a disadvantage to those who are willing to learn; as they refuse to use their own judgment, and rely implicitly on him whom they make choice of for a preceptor.

[tr. Yonge (1877)]In discussion it is not so much authorities as determining reasons that should be looked for. In fact the authority of those who stand forward as teachers is generally an obstacle in the way of those who wish to learn, for the latter cease to apply their own judgment, and take for granted the conclusions which they find arrived at by the teacher whom they approve.

[tr. Brooks (1896)]For when we engage in argument we must look to the weight of reason rather than authority. Indeed, students who are keen to learn often find the authority of those who claim to be teachers to be an obstacle, for they cease to apply their own judgement and regard as definitive the solution offered by the mentor of whom they approve.

[tr. Walsh (2008)]

A good rule for discussion is to use hard facts and a soft voice.

Dorothy Sarnoff (1914-2008) American opera singer, actress, image consultant

Speech Can Change Your Life (1970)

(Source)

For thousands of years people have been trying to force other people to think their way. Did they succeed? No. Will they succeed? No. Why? Because brute force is not an argument.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

Speech to the Jury, Trial of C. B. Reynolds for Blasphemy, Morristown, New Jersey (May 1887)

(Source)

Experts are never right or wrong; they win or lose. Right and wrong are decided by proof; winning and losing are decided by who is doing the talking or talks the loudest, has the last, latest, or only word, and is quoted by reporters.

Silence is a great peacemaker.

When I talk about the death penalty to people, there are a zillion pragmatic arguments to make that the death penalty is more expensive, that you could make mistakes with the death penalty. I try to never use them, because I believe that as soon as I use them, I have dropped what matters to me. Because those arguments are disingenuous. To say, “What if we put an innocent person to death?” I am then telling you that if you can promise me we won’t put any innocent people to death that I’m somehow OK with that, and I’m fucking not. Killing people is wrong. Government shouldn’t fucking do it. End of story.

Penn Jillette (b. 1955) American stage magician, actor, musician, author

Interview by Kahterine Mangu-Ward, Reason (Jan 2017)

(Source)

What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.

Christopher Hitchens (1949-2011) English intellectual, polemicist, socio-political critic

“Mommie Dearest,” Slate (20 Oct 2003)

Sometimes referred to as Hitchens' Razor. The concept is not new (consider the Latin phrase "Quod gratis asseritur, gratis negatur"), but was popularized by Hitchens in discussion of contemporary discussion of religion, including in his work God Is Not Great (2007).

While cited by a number of sources to the 2003 Slate article on the canonization of Mother Teresa, the phrase does not appear in the 2016 reprint of the article at the time she was actually declared a saint.

More information (including the original Slate text): The long history of Hitchens' Razor • Background Probability.

And the funny thing was that people who weren’t entirely certain they were right always argued much louder than other people, as if the main person they were trying to convince were themselves.

A man’s tongue is a glib and twisty thing …

plenty of words there are, all kinds at its command —

with all the room in the world for talk to range and stray.

And the sort you use is just the sort you’ll hear.[Στρεπτὴ δὲ γλῶσσ᾽ ἐστὶ βροτῶν, πολέες δ᾽ ἔνι μῦθοι

παντοῖοι, ἐπέων δὲ πολὺς νομὸς ἔνθα καὶ ἔνθα.

ὁπποῖόν κ᾽ εἴπῃσθα ἔπος, τοῖόν κ᾽ ἐπακούσαις.]Homer (fl. 7th-8th C. BC) Greek author

The Iliad [Ἰλιάς], Book 20, l. 248ff (20.248) [Aeneas] (c. 750 BC) [tr. Fagles (1990), l. 287ff]

(Source)

Original Greek. Alternate translations:A man’s tongue is voluble, and pours

Words out of all sorts ev’ry way. Such as you speak you hear.

[tr. Chapman (1611), ll. 228-29]Armed or with truth or falsehood, right or wrong,

So voluble a weapon is the tongue;

Wounded, we wound; and neither side can fail,

For every man has equal strength to rail.

[tr. Pope (1715-20)]The tongue of man is voluble, hath words

For every theme, nor wants wide field and long,

And as he speaks so shall he hear again.

[tr. Cowper (1791), ll. 309-11]The language of mortals is voluble, and the discourses in it numerous and varied: and vast is the distribution of words here and there. Whatsoever word thou mayest speak, such also wilt thou hear.

[tr. Buckley (1860)]For glibly runs the tongue, and can at will

Give utt’rance to discourse in ev’ry vein;

Wide is the range of language; and such words

As one may speak, another may return.

[tr. Derby (1864)]Glib is the tongue of man, and many words are therein of every kind, and wide is the range of his speech hither and thither. Whatsoever word thou speak, such wilt thou hear in answer.

[tr. Leaf/Lang/Myers (1891)]The tongue can run all whithers and talk all wise; it can go here and there, and as a man says, so shall he be gainsaid.

[tr. Butler (1898)]Glib is the tongue of mortals, and words there be therein many and manifold, and of speech the range is wide on this side and on that. Whatsoever word thou speakest, such shalt thou also hear.

[tr. Murray (1924)]The tongue of man is a twisty thing, there are plenty of words there

of every kind, the range of words is wide, and their variance.

The sort of thing you say is the thing that will be said to you.

[tr. Lattimore (1951)]Men have twisty tongues, and on them speech of all kinds; wide is the grazing land of words, both east and west. The manner of speech you use, the same you are apt to hear.

[tr. Fitzgerald (1974)]Pliant and glib is the tongue men have, and the speeches in it are many and various -- far do the words range hither and thither; such as the word you speak is the word which you will be hearing.

[tr. Merrill (2007)]

Each party abuses the other; the profane and the infidel believe both sides, and enjoy the fray; the reputation of religion in general suffers, and its enemies are ready to say, not what was said in the primitive times, Behold how these Christians love one another, — but, Mark how these Christians HATE one another! Indeed, when religious people quarrel about religion, or hungry people about their victuals, it looks as if they had not much of either among them.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Letter to Jane Mecom (23 Feb 1769)

(Source)

On the vociferous denominational debate in America over whether a new bishop should be sent from the Church of England to the Colonies.

Language is civilization itself. The Word, even the most contradictory word, binds us together. Wordlessness isolates.

Thomas Mann (1875-1955) German writer, critic, philanthropist, Nobel laureate [Paul Thomas Mann]

The Magic Mountain [Der Zauberberg], Part 6, “A Good Soldier” (1924) [tr. Woods]

(Source)

Alt. trans.: "Speech is civilization itself. The word, even the most contradictory word, preserves contact -- it is silence which isolates." [tr. Lowe-Porter]

The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.

Howard G. "Ward" Cunningham (b. 1949) American computer scientist

“Cunningham’s Law”

(Source)

Cunningham himself denies having said this. It was attributed to him (and so named) by Steven McGeady in the early 1980s.

Great causes are never tried on their merits; but the cause is reduced to particulars to suit the size of the partisans, and the contention is ever hottest on minor matters.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“Nature,” Essays: Second Series (1844)

(Source)

All men have a reason, but not all men can give a reason.

William Ralph Inge (1860-1954) English prelate [Dean Inge]

“Implicit Reason and Explicit Reason,” St. Peter’s Day sermon, sec. 9, Oxford University (29 Jun 1840)

(Source)

It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!

Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) American writer, journalist, activist, politician

I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, ch. 20 (1935)

(Source)

A regular comment of his on the campaign trail. The wording is Sinclair's, though there are earlier references with the same sentiment (see here for more discussion).

Often misattributed to H. L. Mencken. (e.g., "Never argue with a man whose job depends on not being convinced") though not found in his work.

It is as absurd to argue men, as to torture them, into believing.

John Henry Newman (1801-1890) English prelate, Catholic Cardinal, theologian

“The Usurpations of Reason,” Sermon, Oxford, England (11 Dec 1831)

(Source)

And I have no desire to get ugly,

But I cannot help mentioning that the door of a bigoted mind opens outwards so that the only result of the pressure of facts upon it is to close it more snugly.

Ogden Nash (1902-1971) American poet

“Seeing Eye to Eye is Believing,” Good Intentions (1942)

(Source)

Maturity begins when we’re content to feel we’re right about something without feeling the necessity to prove someone else wrong.

Sydney J. Harris (1917-1986) Anglo-American columnist, journalist, author

(Attributed)

Frequently attributed to Harris, but the original source has not been found. Earliest citation I could find was in Reader's Digest (1973), where it is further credited to the Publishers-Hall Syndicate.

When blithe to argument I come,

Though armed with facts, and merry,

May Providence protect me from

The fool as adversary,

Whose mind to him a kingdom is

Where reason lacks dominion,

Who calls conviction prejudice

And prejudice opinion.Phyllis McGinley (1905-1978) American author, poet

“Moody Reflections,” The New Yorker (13 Feb 1954)

(Source)

BOB: But that’s okay, because what’s important is that Mommy and I are always a team. We’re always united, against, uh, the forces of, uh —

HELEN: Pig-headed-ness?

BOB: Uh, I was gonna say, “Evil.”Brad Bird (b. 1957) American director, animator and screenwriter [Phillip Bradley Bird]

The Incredibles (2004)

(Source)

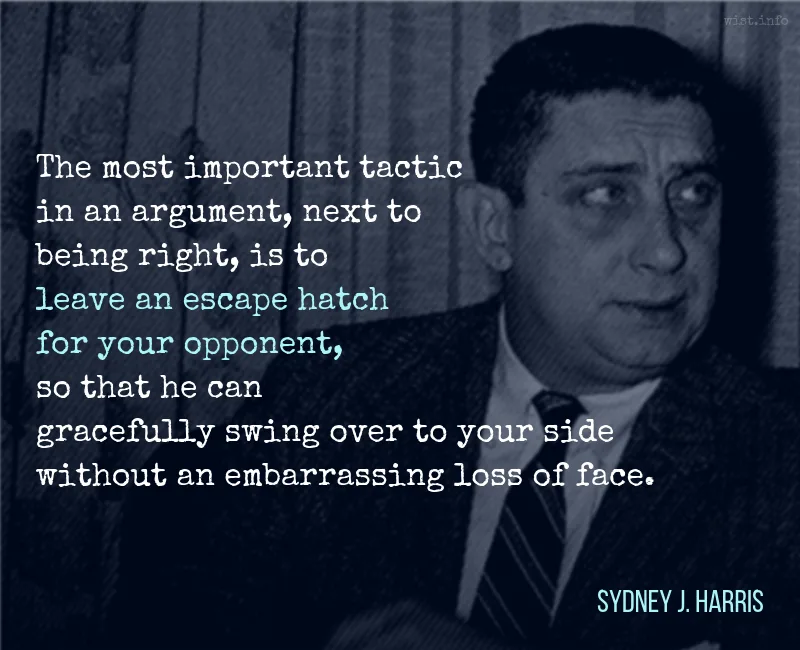

The most important tactic in an argument, next to being right, is to leave an escape hatch for your opponent, so that he can gracefully swing over to your side without an embarrassing loss of face.

Sydney J. Harris (1917-1986) Anglo-American columnist, journalist, author

Pieces of Eight (1982)

(Source)

Frequently misquoted: "The most important thing in an argument, next to being right, is to leave an escape hatch for your opponent, so that he can gracefully swing over to your side without too much apparent loss of face."

Anger blows out the lamp of the mind. In the examination of a great and important question, every one should be serene, slow-pulsed and calm.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

“The Christian Religion,” Article 3, The North American Review (1881)

(Source)

Our disputants put me in mind of the scuttle-fish, that when he is unable to extricate himself, blackens all the water about him, till he becomes invisible.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

The Spectator, #476 (5 Sep 1712)

(Source)

The intoxication of anger, like that of the grape, shows us to others, but hides us from ourselves; and we injure our own cause, in the opinion of the world, when we too passionately and eagerly defend it.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon, Vol. 1, #240 (1820)

(Source)

Every man has a certain sphere of discretion, which he has a right to expect shall not be infringed by his neighbors. This right flows from the very nature of man. First, all men are fallible: no man can be justified in setting up his judgment as a standard for others. We have no infallible judge of controversies; each man in his own apprehension is right in his decisions; and we can find no satisfactory mode of adjusting their jarring pretensions. If every one be desirous of imposing his sense upon others, it will at last come to be a controversy, not of reason, but of force.

William Godwin (1756-1836) English journalist, political philosopher, novelist

Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Book 2, ch. 5 (1793)

(Source)

To have a discussion coolly waived when you feel that justice is all on your side is even more exasperating in marriage than in philosophy.

George Eliot (1819-1880) English novelist [pseud. of Mary Ann Evans]

Middlemarch, Book 3, ch. 24 (1871)

(Source)

One of the greatest advantages of the totalitarian elites of the twenties and thirties was to turn any statement of fact into a question of motive.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) German-American philosopher, political theorist

(Spurious)

This is frequently cited to Arendt, often to The Origins of Totalitarianism, (1951), but is not found as such in her works. The source appears to be a paraphrase of Arendt in a 1999 New Yorker article.

Stuart Elden suggested the following from The Origins of Totalitarianism, Part 3, ch. 11, might be original quotation the paraphrase was built on, though the overall meaning is different:The elite is not composed of ideologists; its members’ whole education is aimed at abolishing their capacity for distinguishing between truth and falsehood, between reality and fiction. Their superiority consists in their ability immediately to dissolve every statement of fact into a declaration of purpose.

Yet at this very point it becomes quite clear that only an act of liberation, not instruction, can overcome stupidity. Here we must come to terms with the fact that in most cases a genuine internal liberation becomes possible only when external liberation has preceded it. Until then we must abandon all attempts to convince the stupid person. This state of affairs explains why in such circumstances our attempts to know what “the people” really think are in vain and why, under these circumstances, this question is so irrelevant for the person who is thinking and acting responsibly.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) German Lutheran pastor, theologian, martyr

“On Stupidity” (1942)

(Source)

Stupidity is a more dangerous enemy of the good than malice. One may protest against evil; it can be exposed and, if need be, prevented by use of force. Evil always carries within itself the germ of its own subversion in that it leaves behind in human beings at least a sense of unease. Against stupidity we are defenseless. Neither protests nor the use of force accomplish anything here; reasons fall on deaf ears; facts that contradict one’s prejudgment simply need not be believed — in such moments the stupid person even becomes critical — and when facts are irrefutable they are just pushed aside as inconsequential, as incidental. In all this the stupid person, in contrast to the malicious one, is utterly self-satisfied and, being easily irritated, becomes dangerous by going on the attack. For that reason, greater caution is called for when dealing with a stupid person than with a malicious one. Never again will we try to persuade the stupid person with reasons, for it is senseless and dangerous.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) German Lutheran pastor, theologian, martyr

“On Stupidity” (1942)

(Source)

If I know your sect, I anticipate your argument.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“Self-Reliance,” Essays: First Series (1841)

(Source)

Aravis also had many quarrels (and, I’m afraid even fights) with Cor, but they always made it up again: so that years later, when they were grown up they were so used to quarreling and making it up again that they got married so as to go on doing it more conveniently.

When the debate is lost, slander becomes the tool of the loser.

Socrates (c.470-399 BC) Greek philosopher

(Spurious)

Of recent coinage. See here for more discussion.

To avoid dissensions we should ever be on our guard, more especially with those who drive us to argue with them, with those who vex and irritate us, and who say things likely to excite us to anger. When we find ourselves in company with quarrelsome, eccentric individuals, people who openly and unblushingly say the most shocking things, difficult to put up with, we should take refuge in silence, and the wisest plan is not to reply to people whose behavior is so preposterous.

Those who insult us and treat us contumeliously are anxious for a spiteful and sarcastic reply: the silence we then affect disheartens them, and they cannot avoid showing their vexation; they do all they can to provoke us and to elicit a reply, but the best way to baffle them is to say nothing, refuse to argue with them, and to leave them to chew the cud of their hasty anger. This method of bringing down their pride disarms them, and shows them plainly that we slight and despise them.

If a couple could see themselves twenty years later they might not recognize their love, but they would recognize their argument.

James Richardson (b. 1950) American poet

Vectors: Aphorisms and Ten-Second Essays, # 20 (2001)

(Source)

Reasoning will never make a Man correct an ill Opinion, which by Reasoning he never acquired.

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) English writer and churchman

“Letter to a Young Clergyman” (9 Jan 1720)

(Source)

Earliest version of this general sentiment, which has been attributed to (or at times borrowed by) figures such as Sydney Smith, Fisher Ames, and Lyman Beecher.

For more information about this quotation: You Cannot Reason People Out of Something They Were Not Reasoned Into – Quote Investigator.

Everyone is prejudiced in favor his own powers of discernment, and will always find an argument most convincing if it leads to the conclusion he has reached for himself; everyone must then be given something he can grasp and recognize as his own idea.

Earthly minds, like mud walls, resist the strongest batteries: and though, perhaps, sometimes the force of a clear argument may make some impression, yet they nevertheless stand firm, and keep out the enemy, truth, that would captivate or disturb them. Tell a man passionately in love that he is jilted; bring a score of witnesses of the falsehood of his mistress, it is ten to one but three kind words of hers shall invalidate all their testimonies.

This is the character of truth: it is of all time, it is for all men, it has only to show itself to be recognized, and one cannot argue against it. A long dispute means that both parties are wrong.

Voltaire (1694-1778) French writer [pseud. of Francois-Marie Arouet]

Philosophical Dictionary, “Sect” (1764) [tr. Gay (1962)]

(Source)

Our errors and our controversies, in the sphere of morality, arise sometimes from looking on men as though they could be altogether bad, or altogether good.

[Nos erreurs et nos divisions dans la morale viennent quelquefois de ce que nous considérons les hommes comme s’ils pouvaient être tout à fait vicieux ou tout à fait bons.]

Luc de Clapiers, Marquis de Vauvenargues (1715-1747) French moralist, essayist, soldier

Reflections and Maxims [Réflexions et maximes], # 31 (1746) [tr. Stevens (1940)]

(Source)

It would be almost unbelievable, if history did not record the tragic fact that men have gone to war and cut each other’s throat because they could not agree as to what was to become of them after their throats were cut. Many sins have been committed in the name of religion. Alas! the spirit of proscription is never kind. It is the unhappy quality of religious disputes that they are always bitter. For some reason, too deep to fathom, men contend more furiously over the road to heaven, which they cannot see, than over their visible walks on earth.

In disputes upon moral or scientific points, ever let your aim be to come at truth, not to conquer your opponent: so you never shall be at a loss in losing the argument, and gaining a new discovery.

James Burgh (1714-1775) British politician and writer

The Dignity of Human Nature, Sec. 5 “Miscellaneous Thoughts on Prudence in Conversation” (1754)

(Source)

An eagerness and zeal for dispute on every subject, and with every one, shows great self-sufficiency, that never-failing sign of great self-ignorance.

If you mean to make your side of the argument appear plausible, do not prejudice the people against what you think truth by your passionate manner of defending it.

James Burgh (1714-1775) British politician and writer

The Dignity of Human Nature, Sec. 5 “Miscellaneous Thoughts on Prudence in Conversation” (1754)

(Source)

What Tully said of war may be applied to disputing: “It should be always so managed as to remember that the only true end of it is peace.” But generally true disputants are like true sportsmen, — their whole delight is in the pursuit; and the disputant no more cares for the truth than the sportsman for the hare.

Prejudice, not being founded on reason, cannot be removed by argument.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) English writer, lexicographer, critic

(Spurious)

(Source)

Frequently attributed without citation, and not found in Johnson's works. However, the phrase can be found in other contexts:

- "This objection on the score of color is founded upon prejudice, and hence cannot be removed by argument, for prejudice is blind and listens not to reason." -- Rep. Godlove S. Orth of Indiana, speech before the House of Representatives (5 Apr 1869) on the question of admitting the Dominican Republic as a US territory.

- "This persuasion of the power of the priest is, as we have said, a traditional prejudice; it is not founded on any reasons or proofs addressed to the understanding, and therefore it cannot be removed by argument." -- John Eliot Howard, The Island of the Saints (1855), quoting from the Achill Herald (Jun 1855).

But in stating prudential rules for our government in society I must not omit the important one of never entering into dispute or argument with another. I never yet saw an instance of one of two disputants convincing the other by argument. I have seen many of their getting warm, becoming rude, & shooting one another. Conviction is the effect of our own dispassionate reasoning, either in solitude, or weighing within ourselves dispassionately what we hear from others standing uncommitted in argument ourselves.

When a subject is highly controversial — and any question about sex is that — one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one’s audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the limitations, the prejudices, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker.

An association of men who will not quarrel with one another is a thing which never yet existed, from the greatest confederacy of nations down to a town meeting or a vestry.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American political philosopher, polymath, statesman, US President (1801-09)

Letter to John Taylor (4 Jun 1798)

(Source)

In the end is it not futile to try and follow the course of a quarrel between husband and wife? Such a conversation is sure to meander more than any other. It draws in tributary arguments and grievances from years before — all quite incomprehensible to any but the two people they concern most nearly. Neither party is ever proved right or wrong in such a case, or, if they are, what does it signify?

Don’t argue with idiots because they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.

Greg King (b. 1964) American author and biographer

(Attributed)

Often attributed to Twain (compare to this), Bob Smith, George Carlin, and John Guerrero, all without citation. See also Proverbs 26:4.

Never argue with a fool; onlookers may not be able to tell the difference.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

(Spurious)

Frequently attributed to Twain and also to Immanuel Kant (but never, in either case, with any citation). The phrase first makes recognizable (if anonymous) appearance in the late 19th Century; attributions to Twain begin in the late 1990s. See also Proverbs 26:4. For more discussion (and a shout-out to WIST) see here.

I never make the mistake of arguing with people for whose opinions I have no respect.

Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) English historian

(Attributed)

Answer not a fool according to his folly, lest thou also be like unto him.

The Bible (The Old Testament) (14th - 2nd C BC) Judeo-Christian sacred scripture [Tanakh, Hebrew Bible], incl. the Apocrypha (Deuterocanonicals)

Proverbs 26:4 [KJV (1611)]

(Source)

Alternate translations:Do not answer a fool in the terms of his folly for fear you grow like him yourself.

[JB (1966)]If you answer a silly question, you are just as silly as the person who asked it.

[GNT (1976)]Do not answer a fool in the terms of his folly for fear you grow like him yourself.

[NJB (1985)]Don’t answer fools according to their folly,

or you will become like them yourself.

[CEB (2011)]Do not answer fools according to their folly,

lest you be a fool yourself.

[NRSV (2021 ed.)]Do not answer a dullard in accord with his folly,

Else you will become like him.

[RJPS (2023 ed.)]

In a Debate, rather pull to Pieces the Argument of thy Antagonist than offer him any of thy own; for thus thou wilt fight him in his own Country.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 1, # 766 (1725)

(Source)

It is only when they cannot answer your reasons, that they wish to knock you down.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“The Assault upon Mr. Sumner,” speech, Concord (1856-05-26)

(Source)

I am bound to furnish my antagonists with arguments, but not with comprehension.

Everyone is in favor of free speech. Hardly a day passes without its being extolled, but some people’s idea of it is that they are free to say what they like, but if anyone says anything back, that is an outrage.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965) British statesman and author

Debate, House of Commons (13 Oct 1943)

(Source)

More discussion of this quotation: If Anyone Says Anything Back, That Is an Outrage – Quote Investigator.

Passionate expression and vehement assertion are no arguments, unless it be of the weakness of the cause that is defended by them, or of the man that defends it.

William Chillingworth (1602-1644) English churchman and theologian

(Attributed)

(Source)

Quoted in The Parliamentary History of England, Vol. 15, 29 George II, "Debate on a Motion for a Vote of Censor on the Treaties with Russia and Hesse Cassel (1755)" (1813)

To keep your marriage brimming,

With love in the loving cup,

Whenever you’re wrong, admit it;

Whenever you’re right, shut up.Ogden Nash (1902-1971) American poet

“A Word to Husbands,” Marriage Lines: Notes of a Student Husband (1964)

(Source)

Be brief, be pointed, let your matter stand

Lucid in order, solid and at hand;

Spend not your words on trifles but condense;

Strike with the mass of thought, not drops of sense;

Press to close with vigor, once begun,

And leave, (how hard the task!) leave off, when done.

We ought in fairness to fight our case with no help beyond the bare facts: nothing, therefore, should matter except the proof of those facts. Still, as has been already said, other things affect the result considerably, owing to the defects of our hearers.

[δίκαιον γὰρ αὐτοῖς ἀγωνίζεσθαι τοῖς πράγμασιν, ὥστε τἆλλα ἔξω τοῦ ἀποδεῖξαι περίεργα ἐστίν: ἀλλ᾽ ὅμως μέγα δύναται, καθάπερ εἴρηται, διὰ τὴν τοῦ ἀκροατοῦ μοχθηρίαν.]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Rhetoric [Ῥητορική; Ars Rhetorica], Book 3, ch. 1, sec. 5 (3.1.5) / 1404a (350 BC) [tr. Roberts (1924)]

(Source)

On style vs. substance in shaping judgment. (Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:For justice would be to contend with the facts only, so that every thing else beside the mere demonstration is superfluous; nevertheless, it [style] is of great influence, as has been said, owing to the corruption of the hearers.

[Source (1847)]Our facts ought to be our sole weapons, making everything superfluous which is outside the proof; owing to the infirmities of the hearer, however, style, as we have said, can do much.

[tr. Jebb (1873)]For justice should consist in fighting the case with the facts alone, so that everything else that is beside demonstration is superfluous; nevertheless, as we have just said, it [style] is of great importance owing to the corruption of the hearer.

[tr. Freese (1926)]Although [...] in justice, litigants should appeal only to the facts to contest the case, so that everything apart from demonstration is superfluous, it remains the case, as I have aid, that, thanks to the audience's moral weakness, delivery is very effective.

[tr. Waterfield (2018)]

It is very natural for young men to be vehement, acrimonious and severe. For as they seldom comprehend at once all the consequences of a position, or perceive the difficulties by which cooler and more experienced reasoners are restrained from confidence, they form their conclusions with great precipitance. Seeing nothing that can darken or embarrass the question, they expect to find their own opinion universally prevalent, and are inclined to impute uncertainty and hesitation to want of honesty, rather than of knowledge.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) English writer, lexicographer, critic

The Rambler, #121 (14 May 1751)

(Source)

DICKINSON: Mr. Jefferson, Mr. Lee, Mr. Hopkins, Dr. Franklin, why have you joined this — incendiary little man, this BOSTON radical? This demagogue, this MADMAN?

ADAMS: Are you calling me a madman, you, you — you FRIBBLE!

FRANKLIN: Easy, John.

ADAMS: You cool, considerate men — you hang to the rear on every issue so that if we should go under, you’ll still remain afloat!

DICKINSON: Are you calling me a coward?

ADAMS: Yes — coward!

DICKINSON: Madman!

ADAMS: Landlord!

DICKINSON: LAWYER!

[A brawl breaks out]

If a donkey bray at you, don’t bray at him.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

(Attributed)

Often attributed to Herbert, but not found in his works. Elsewhere listed simply as a proverb.

I love to see two truths at the same time. Every good comparison gives the mind this advantage.

[J’aime à voir deux vérités à la fois. Toute bonne comparaison donne à l’esprit cet avantage.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], Introduction, “L’auteur Peint par Lui-Même [The Author’ Self-Portrait]” (1850 ed.) [tr. Auster (1983)], 1796]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:I like to see two truths at once. Every good comparison gives the mind this advantage.

[tr. Calvert (1866), "Notice"]I like to see two truths at once. Every good comparison gives the mind that advantage.

[tr. Collins (1928)]

In the middle ages of Christianity opposition to the State opinions was hushed. The consequence was, Christianity became loaded with all the Romish follies. Nothing but free argument, raillery, and even ridicule will preserve the purity of religion.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American political philosopher, polymath, statesman, US President (1801-09)

“Notes on Religion” (1776-10?)

(Source)

Labeled by Jefferson "Scraps Early in the Revolution." Modern phrasing. Original:In the middle ages of Xty opposition to the State opins was hushed. The consequence was, Xty became loaded with all the Romish follies. Nothing but free argument, raillery & even ridicule will preserve the purity of religion.

Do not think of knocking out another person’s brains because he differs in opinion from you. It would be as rational to knock yourself on the head because you differ from yourself ten years ago.

To refuse a hearing to an opinion because they are sure that it is false, is to assume that their certainty is the same thing as absolute certainty. All silencing of discussion is an assumption of infallibility.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) English philosopher and economist

On Liberty, ch. 2 “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion” (1859)

(Source)

Goe not for every griefe to the Physitian, nor for every quarrell to the Lawyer, nor for every thirst to the pot.

George Herbert (1593-1633) Welsh priest, orator, poet.

Jacula Prudentum, or Outlandish Proverbs, Sentences, &c. (compiler), # 290 (1640 ed.)

(Source)

Be not magisterial in thy Dictates, nor pertinaciously contentious in ordinary discourse for thy Opinion; no nor for even a Truth of small Consequence. If thou thinkest good, declare thy Reasons; if they be not accepted, be quiet, and let them alone. Thou are not bound to convert all the World to Truth.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 1, # 1557 (1725)

(Source)

I have seen a man of genius who made one think if other men were like him, cooperation were impossible. Must we always talk for victory, and never once for truth, for comfort, and joy?

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“Table Talk,” American Life, lecture, Boston (1864-12-18)

(Source)

Speaking of Thoreau's style of conversation. Originally a Journal entry of 29 Feb 1856. Also part of the lecture "Social Aims".

He that hath the worst Cause, makes the most Noise.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs, #2153 (1732)

(Source)

Intellectual honesty and obvious sincerity carry more conviction than was ever accomplished by mere utterance. The advocate can make no greater mistake than to ignore or attempt to conceal the weak points in his case. The most effective strategy is at an early stage of the argument to invite attention to your weakest point before the court has discovered it, then to meet it with the best answers at your disposal, to deal with all the remaining points with equal candor, and to end with as powerful a presentation of your strongest point as you are capable of making.

George W. Pepper (1867-1961) American lawyer, law professor, politician

Letter to Eugene Gerhart (1951-12-10)

(Source)

Quoted in Gerhart, America's Advocate: Robert H. Jackson, ch. 24 (1958).

The end of an argument or discussion should be, not victory, but enlightenment.

[Le but de la dispute ou de la discussion ne doit pas être la victoire, mais l’amélioration.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 8, ¶ 41 (1850 ed.) [tr. Collins (1928), ch. 7]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:The aim of disputation and discussion should not be victory, but improvement.

[tr. Calvert (1866), ch. 8]The aim of argument, or of discussion, should not be victory, but progress.

[tr. Lyttelton (1899), ch. 7, ¶ 31]

You mustn’t exaggerate, young man. That’s always a sign your argument is weak.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

“Redbook Dialogue,” interview by Tommy Robbins, Redbook (1964-09)

(Source)

Reprinted in Russell Society News, #37 (1983-02), p. 24.

So then, I am simply in favor of intellectual hospitality — that is all. You come to me with a new idea. I invite you into the house. Let us see what you have. Let us talk it over. If I do not like your thought, I will bid it a polite “good day.” If I do like it, I will say: “Sit down; stay with me, and become a part of the intellectual wealth of my world.” That is all.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

“The Limits of Toleration,” debate at the Nineteenth Century Club, New York (8 May 1888)

(Source)

Great virtues may draw attention from defects, they cannot sanctify them. A pebble surrounded by diamonds remains a common stone, and a diamond surrounded by pebbles is still a gem. No one should attempt to refute an argument by pronouncing the name of some man, unless he is willing to adopt all the ideas and beliefs of that man. It is better to give reasons and facts than names. An argument should not depend for its force upon the name of its author. Facts need no pedigree, logic has no heraldry, and the living should not awed by the mistakes of the dead.

Robert Green Ingersoll (1833-1899) American lawyer, agnostic, orator

“The Great Infidels” (1881)

(Source)

Many a long dispute among Divines may be thus abridg’d, It is so; It is not so. It is so; It is not so.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) American statesman, scientist, philosopher, aphorist

Poor Richard’s Almanack (1743)

(Source)

I used to say that, as Solicitor General, I made three arguments in every case. First came the one I had planned — as I thought, logical, coherent, complete. Second was the one actually presented — interrupted, incoherent, disjointed, disappointing. The third was the utterly devastating argument that I thought of after going to bed that night.

Robert H. Jackson (1892-1954) US Supreme Court Justice (1941-54), lawyer, jurist, politician

“Advocacy Before the Supreme Court,” Morrison Lecture, California State Bar (23 Aug 1951)

(Source)

Reprinted in the Cornell Law Quarterly (Fall 1951). Legal citation "Advocacy Before the Supreme Court," 37 A.B.A.J. 801, 803 (1951).

[Arguments] seem unable to influence the masses in the direction of what is noble and good. For the masses naturally obey fear, not shame, and abstain from shameful acts because of the punishments associated with them, not because they are disgraceful.

[τοὺς δὲ πολλοὺς ἀδυνατεῖν πρὸς καλοκαγαθίαν προτρέψασθαι: οὐ γὰρ πεφύκασιν αἰδοῖ πειθαρχεῖν ἀλλὰ φόβῳ, οὐδ᾽ ἀπέχεσθαι τῶν φαύλων διὰ τὸ αἰσχρὸν ἀλλὰ διὰ τὰς τιμωρίας]

Aristotle (384-322 BC) Greek philosopher

Nicomachean Ethics [Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια], Book 10, ch. 9 (10.9.3-4) / 1179b.10ff (c. 325 BC) [tr. Crisp (2000)]

(Source)

(Source (Greek)). Alternate translations:[Talking and writing] plainly are powerless to guide the mass of men to Virtue and goodness; because it is not their nature to be amenable to a sense of shame but only to fear; nor to abstain from what is low and mean because it is disgraceful to do it but because of the punishment attached to it

[tr. Chase (1847), ch. 8]But, for most men, mere precept is powerless to dispose them to noble conduct. For their nature is such, that they are not ruled by a proper sense of shame, but only by fear, and do not abstain from vice because of the disgrace which attaches to it, but because of the punishment which its practice involves.

[tr. Williams (1869)][Theories] are impotent to inspire the mass of men to chivalrous action; for it is not the nature of such men to obey honour but terror, nor to abstain from evil for fear of disgrace but for fear of punishment.

[tr. Welldon (1892)]Yet [theories] are powerless to turn the mass of men to goodness. For the generality of men are naturally apt to be swayed by fear rather than by reverence, and to refrain from evil rather because of the punishment that it brings than because of its own foulness.

[tr. Peters (1893)][Arguments] are not able to encourage the many to nobility and goodness. For these do not by nature obey the sense of shame, but only fear, and do not abstain from bad acts because of their baseness but through fear of punishment.

[tr. Ross (1908)]Yet [theories] are powerless to stimulate the mass of mankind to moral nobility. For it is the nature of the many to be amenable to fear but not to a sense of honor, and to abstain from evil not because of its baseness but because of the penalties it entails.

[tr. Rackham (1934)][Arguments are] unable to encourage ordinary people toward noble-goodness. For ordinary people naturally obey not shame but fear and abstain from base things not because of their shamefulness but because of the sanctions involved.

[tr. Reeve (1948)][Arguments] cannot exhort ordinary men to do good and noble deeds, for it is the nature of these men to obey not a sense of shame but fear, and to abstain from what is bad not because this is disgraceful but because of the penalties which they would receive.

[tr. Apostle (1975)][Discourses] are incapable of impelling the masses toward human perfection. For it is the nature of the many to be ruled by fear rather than by shame, and to refrain from evil not because of the disgrace but because of the punishments.

[tr. Thomson/Tredennick (1976)]But [arguments] seem unable to turn the many toward being fine and good. For the many naturally obey fear, not shame; they avoid what is base because of the penalties, not because it is disgraceful.

[tr. Irwin/Fine (1995)]

We cannot define anything precisely! If we attempt to, we get into that paralysis of thought that comes to philosophers who sit opposite each other, one saying to the other, “You don’t know what you are talking about!”. The second one says, “What do you mean by know? What do you mean by talking? What do you mean by you?” and so on.

Richard Feynman (1918-1988) American physicist

The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Volume I, 8-2 “Motion” (20 Oct 1961)

(Source)

To argue with a man who has renounced the use and authority of reason, and whose philosophy consists in holding humanity in contempt, is like administering medicine to the dead, or endeavoring to convert an Atheist by scripture.

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) American political philosopher and writer

The American Crisis #5, “To General Sir William Howe” (23 Mar 1778)

(Source)

Sometimes shortened as: "To argue with a man who has renounced his reason is like giving medicine to the dead."

The most perfidious way of damaging a cause is deliberately to defend it with faulty arguments.

[Die perfideste Art, einer Sache zu schaden ist, sie absichtlich mit fehlerhaften Gründen vertheidigen.]

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) German philosopher and poet

The Gay Science [Die fröhliche Wissenschaft], Book 3, § 191 (1882) [tr. Nauckhoff (2001)]

(Source)

Also known as La Gaya Scienza, The Joyful Wisdom, or The Joyous Science.

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:The most perfidious manner of injuring a cause is to vindicate it intentionally with fallacious arguments.

[tr. Common (1911)]The most perfidious way of harming a cause consists of defending it deliberately with faulty arguments.

[tr. Kaufmann (1974)]One injures a cause in the most perfidious manner by deliberately defending it with erroneous reasons.

[tr. Hill (2018)]

The idea that any kind of free society can be constructed in which people will never be offended or insulted is absurd. So too is the notion that people should have the right to call on the law to defend them against being offended or insulted. A fundamental decision needs to be made: do we want to live in a free society or not? Democracy is not a tea party where people sit around making polite conversation. In democracies people get extremely upset with each other. They argue vehemently against each other’s positions. (But they don’t shoot.)

Salman Rushdie (b. 1947) Indian novelist

“Do we have to fight the battle for the Enlightenment all over again?” The Independent (22 Jan 2005)

(Source)

At Cambridge University I was taught a laudable method of argument: you never personalise, but you have absolutely no respect for people’s opinions. You are never rude to the person, but you can be savagely rude about what the person thinks. That seems to me a crucial distinction: people must be protected from discrimination by virtue of their race, but you cannot ring-fence their ideas. The moment you say that any idea system is sacred, whether it’s a religious belief system or a secular ideology, the moment you declare a set of ideas to be immune from criticism, satire, derision, or contempt, freedom of thought becomes impossible.

Salman Rushdie (b. 1947) Indian novelist

“Do we have to fight the battle for the Enlightenment all over again?” The Independent (22 Jan 2005)

(Source)

DISCUSSION, n. A method of confirming others in their errors.

Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914?) American writer and journalist

“Discussion,” The Cynic’s Word Book (1906)

(Source)

Included in The Devil's Dictionary (1911). Originally published in the "Devil's Dictionary" column in the San Francisco Wasp (1882-04-02).

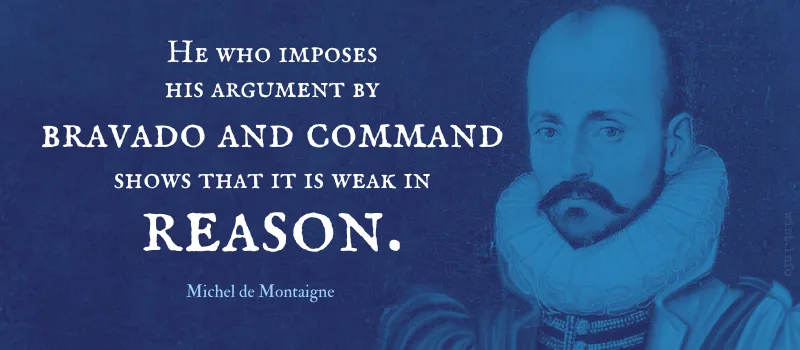

He who imposes his argument by bravado and command shows that it is weak in reason.

[Qui establit son discours par braverie et commandement, montre que la raison y est foible.]Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 3, ch. 11 “Of Cripples [Des Boyteux]” (1587) (3.11) (1595) [tr. Frame (1943)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:He that with braverie and by comaundement will establish his discourse, declareth his reason to be weake.

[tr. Florio (1603), "Of the Lame or Cripple"]Who will establish his Discourse by Authority and Huffing, discovers his Reason to be very weak.

[tr. Cotton (1686)]He who will establish this proposition by authority and huffing discovers his reason to be very weak.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877), "On the Lame"]He who establishes his argument by defiance and by command shews that his reasoning is weak.

[tr. Ives (1925)]Any man who supports his opinion with challenges and commands demonstrates that his reasons for it are weak.

[tr. Screech (1987), "On the Lame"]He who establishes his argument by noise and command shows that his reason is weak.

[Source]

Truth is great and will prevail if left to herself. She is the proper and sufficient antagonist to error, and has nothing to fear from conflict, unless by human interposition disarmed of her natural weapons, free argument and debate, errors ceasing to be dangerous when it is permitted freely to contradict them.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American political philosopher, polymath, statesman, US President (1801-09)

“Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom,” Preamble (1776-06-18; enacted 1786-01-16)

(Source)

How many a debate could have been deflated into a single paragraph if the disputants had dared to define their terms?

William James (Will) Durant (1885-1981) American historian, teacher, philosopher

The Story of Philosophy, ch. 2 “Aristotle and Greek Science,” sec. 3 “The Foundation of Logic” (1926)

(Source)

This quotation is frequently misattributed (without citation) to Aristotle (sometimes using "dispute" instead of "debate"), but none of the sources pre-date this passage by Durant. Durant is speaking of Aristotle's development of logic, and his focus on definitions, but the full passage in context is clearly not a quotation:There was a hint of this new science in Socrates’ maddening insistence on definitions, and in Plato’s constant refining of every concept. Aristotle’s little treatise on Definitions shows how his logic found nourishment at this source. “If you wish to converse with me,” said Voltaire, “define your terms.” How many a debate would have been deflated into a paragraph if the disputants had dared to define their terms! This is the alpha and omega of logic, the heart and soul of it, that every important term in serious discourse shall be subjected to strictest scrutiny and definition. It is difficult, and ruthlessly tests the mind; but once done it is half of any task.

There are two things which cannot be attacked in front: ignorance and narrow-mindedness. They can only be shaken by the simple development of the contrary qualities. They will not bear discussion.

John Dalberg, Lord Acton (1834-1902) British historian, politician, writer

Letter (1861-01-23) to Richard Simpson

(Source)

Matters of religion should never be matters of controversy. We neither argue with a lover about his taste, not condemn him, if we are just, for knowing so human a passion.

George Santayana (1863-1952) Spanish-American poet and philosopher [Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruíz de Santayana y Borrás]

The Life of Reason or The Phases of Human Progress, Vol. 3 “Reason in Religion,” ch. 6 “The Christian Epic” (1905-06)

(Source)

Anyone who in discussion relies upon authority uses, not his understanding, but his memory.

Faced with the choice between changing one’s mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy on the proof.

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908-2006) Canadian-American economist, diplomat, author

Economics, Peace and Laughter (1971)

(Source)

(also called "Galbraith's Law")

It is better to debate a question without settling it, than to settle it without debate.

[Il vaut mieux remuer une question sans la décider, que la décider sans la remuer.]

Joseph Joubert (1754-1824) French moralist, philosopher, essayist, poet

Pensées [Thoughts], ch. 8 “De la Famille et de la Société, etc. [On the Family and Society]” ¶ 71 (1850 ed.) [tr. Attwell (1896), ¶ 115]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:It is better to stir a question without deciding it, than to decide it without stirring it.

[tr. Calvert (1866), ch. 8]It is better to turn over a question without deciding it, than to decide it without turning it over.

[tr. Lyttelton (1899), ch. 7, ¶ 61]It is better to stir up a question without deciding it, than to decide it without stirring it up.

[tr. Collins (1928), ch. 7]It is better to debate a question without settling it than to settle a question without debating it.

[Variant]

He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) English philosopher and economist

On Liberty, ch. 2 “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion” (1859)

(Source)

He uses statistics as a drunkard uses a lamppost — for support rather than for illumination.

Andrew Lang (1844-1912) Scottish writer, journalist, historian

(Attributed)

Original source not found, but attributed by several sources to Lang in 1937, possibly derived from a comment by A. E. Houseman. More information here.

Men will wrangle for religion; write for it; fight for it; die for it; anything but — live for it.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon: Or, Many Things in Few Words, Vol. 1, § 25 (1820)

(Source)

‘Twas the saying of an ancient Sage, “That Humour was the only Test of Gravity, and Gravity of Humour. For a Subject which would not bear Raillery is suspicious; and a Jest which would not bear a serious Examination is certainly false Wit.”

Anthony Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713) English politician and philosopher

Sensus Communis: An Essay on the Freedom of Wit and Humour, Part 1, Sec. 5 (1709)

(Source)

Often incorrectly attributed to Aristotle. Shaftesbury, according to his footnote, is paraphrasing from Aristotle quoting Gorgias Leontinus. The Latin translation is "Seria risu, risum seriis discutere" ("In arguing one should meet serious pleading with humor, and humor with serious pleading"). Shaftesbury's second sentence is his own commentary.

In Lord Chesterfield, in a letter to his son (6 Feb 1752), rendered it, "Ridicule is the best test of truth."