In teaching thy Child, rather dally with him, than terrify him: for no Art or Science entereth kindly into the Mind, that is driven in forcibly.

Thomas Fuller (1654-1734) English physician, preacher, aphorist, writer

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 1, # 1181 (1725)

(Source)

Quotations about:

learning

Note not all quotations have been tagged, so Search may find additional quotes on this topic.

In teaching thy Child, rather dally with him, than terrify him: for no Art or Science entereth kindly into the Mind, that is driven in forcibly.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

Introductio ad Prudentiam, Vol. 1, # 1181 (1725)

(Source)

Knowledge is, indeed, that which, next to virtue, truly and essentially raises one man above another. It finishes one half of the human Soul. It makes Being pleasant to us, fills the mind with entertaining views, and administers to it a perpetual series of gratifications. It gives ease to solitude and gracefulness to retirement. It fills a publick station with suitable abilities, and adds a lustre to those who are in possession of them.

Joseph Addison (1672-1719) English essayist, poet, statesman

Essay (1713-07-18), The Guardian, No. 111

(Source)

Don’t say “When I have time I will learn,” lest you never have time.

[וְאַל תֹּאמַר לִכְשֶׁאִפָּנֶה אֶשְׁנֶה, שֶׁמָּא לֹא תִפָּנֶה:]

Hillel (1st C. BC-1st C. AD) Jewish sage, rabbi [הלל]

Mishna, Seder Nezikin [Order of Damages], Pirkei Avot [Chapters of the Fathers] 2:4

(Source)

(Source (Hebrew)). Alternate translations:Say not, When I have leisure I will study; perchance thou mayest not have leisure.

[tr. Taylor (1897)]Say not: ‘when I shall have leisure I shall study;’ perhaps you will not have leisure.

[tr. Gorfinkle (1913)]Say not: ‘when I shall have leisure I shall study;’ perhaps you will not have leisure.

[tr. Kulp]Do not say: When I can free myself [of my affairs] I shall learn (Torah); perhaps you will not free yourself.

[tr. Shraga Silverstein]Do not say, "When I will be available I will study [Torah]," lest you never become available.

[Open Mishnah]Do not say "When I have leisure, I will study," perhaps you will not have leisure.

[Source]Say not, "When I have free time I shall study"; for you may perhaps never have any free time.

A fresh hope is astir. From many quarters comes the call to a new kind of education with its initial assumption affirming that education is life — not a mere preparation for an unknown kind of future living. Consequently all static concepts of education which relegate the learning process to the period of youth are abandoned. The whole of life is learning, therefore education can have no endings,

Eduard C. Lindeman (1885-1953) American educator

The Meaning of Adult Education, ch. 1 (1926)

(Source)

Poverty must not be a bar to learning, and learning must offer an escape from poverty.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) American politician, educator, US President (1963-69)

Speech (1964-05-22), Graduation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

(Source)

§ 94. But why should every individual not have been present more than once in this world?

§ 95. Is this hypothesis so ridiculous just because it is the oldest one? Because the human understanding hit up on it at once, before it was distracted and weakened by the sophistry of the schools?

§ 98. Why should I not come back as often as I am able to acquire new knowledge and new accomplishments? Do I take away so much on one occasion that it may not be worth the trouble coming back?

§ 100. Or am I not to return because too much time would be lost in so doing? — Lost? — And what exactly do I have to lose? Is not the whole of eternity mine?[§ 94. Aber warum könnte jeder einzelne Mensch auch nicht mehr als einmal auf dieser Welt vorhanden gewesen seyn?

§ 95. Ist diese Hypothese darum so lächerlich, weil sie die älteste ist? weil der menschliche Verstand, ehe ihn die Sophisterey der Schule zerstreut und geschwächt hatte, sogleich darauf verfiel?

§ 98. Warum sollte ich nicht so oft wiederkommen, als ich neue Kenntnisse, neue Fertigkeiten zu erlangen geschickt bin? Bringe ich auf Einmal so viel weg, daß es der Mühe wieder zu kommen etwa nicht lohnet?

§ 100. Oder, weil so zu viel Zeit für mich verloren gehen würde?—Verloren? —Und was habe ich denn zu versäumen? Ist nicht die ganze Ewigkeit mein?]Gotthold Lessing (1729-1781) German playwright, philosopher, dramaturg, writer

The Education of the Human Race [Die Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts] (1780)

(Source)

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:§ 94. But why should not every individual man have existed more than once upon this World?

§ 95. Is this hypothesis so laughable merely because it is the oldest? Because the human understanding, before the sophistries of the Schools had dissipated and debilitated it, lighted upon it at once?

§ 98. Why should I not come back as often as I am capable of acquiring fresh knowledge, fresh expertness? Do I bring away so much from once, that there is nothing to repay the trouble of coming back?

§ 100. Or is it a reason against the hypothesis that so much time would have been lost to me? Lost? -- And how much then should I miss? -- Is not a whole Eternity mine?

[tr. Robertson (1862)]§ 94. But why could not each individual man Have been existent on this earth more than once?

§ 95. Is this hypothesis therefore so absurd because it is the oldest, because the human understanding, ere enfeebled and scattered by sophistry, immediately hit upon it?

§ 98. Why may I not return as often as I am fit to acquire new knowledge, new skill? Do I bring away so much at once that there is not wherewith to recompense the burden of return?

§ 100. Or is it because too much time would thus for me be lost? Lost? And what have I to lose? Is not mine a whole eternity?

[tr. Haney (1908)]

The object of education for that mind should be the teaching itself how to react with vigor and economy. No doubt the world at large will always lag so far behind the active mind as to make a soft cushion of inertia to drop upon, as it did for Henry Adams; but education should try to lessen the obstacles, diminish the friction, invigorate the energy, and should train minds to react, not at haphazard, but by choice, on the lines of force that attract their world. What one knows is, in youth, of little moment; they know enough who know how to learn.

Henry Adams (1838-1918) American journalist, historian, academic, novelist

The Education of Henry Adams, ch. 21 (1907)

(Source)

Education is that which remains, if one has forgotten everything else he learned in school.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) German-American physicist

(Misattributed)

(Source)

Einstein cites this (as he agrees with it) as coming from a "wit" in a speech (1936-10-15), Convocation of University of New York, Albany [tr. Arronet]. Collected in "On Education" (1936), Out of My Later Years, ch. 9 (1950).

Pedantry crams our heads with learned lumber, and takes out our brains to make room for it.

Charles Caleb "C. C." Colton (1780-1832) English cleric, writer, aphorist

Lacon: Or, Many Things in Few Words, Vol. 2, § 20 (1822)

(Source)

The central task of education is to implant a will and facility for learning; it should produce not learned but learning people. The truly human society is a learning society, where grandparents, parents, and children are students together.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Reflections on the Human Condition, ch. 1, # 32 (1973)

(Source)

Elitism is repulsive when based upon external and artificial limitations like race, gender, or social class. Repulsive and utterly false — for that spark of genius is randomly distributed across all cruel barriers of our social prejudice. We therefore must grant access — and encouragement — to everyone; and must be increasingly vigilant, and tirelessly attentive, in providing such opportunities to all children. We will have no justice until this kind of equality can be attained. But if only a small minority respond, and these are our best and brightest of all races, classes, and genders, shall we deny them the pinnacle of their soul’s striving because all their colleagues prefer passivity and flashing lights? Let them lift their eyes to hills of books, and at least a few museums that display the full magic of nature’s variety. What is wrong with this truly democratic form of elitism?

Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002) American paleontologist, geologist, biologist

Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History, Part 5, ch. 18 “Cabinet Museums: Alive, Alive, O!” (1995)

(Source)

Only if a child feels right can he think right.

Haim Ginott (1922-1973) Israeli-American school teacher, child psychologist, psychotherapist [b. Haim Ginzburg]

Teacher and Child, ch. 4 “Congruent Communication” (1972)

(Source)

Writing, printing, and the Internet give a false sense of security about the permanence of culture. Most of the million details of a complex, living culture are transmitted neither in writing nor pictorially. Instead, cultures live through word of mouth and example. That is why we have cooking classes and cooking demonstrations, as well as cookbooks. That is why we have apprenticeships, internships, student tours, and on-the-job training as well as manuals and textbooks. Every culture takes pains to educate its young so that they, in their turn, can practice and transmit it completely. Educators and mentors, whether they are parents, elders, or schoolmasters, use books and videos if they have them, but they also speak, and when they are most effective, as teachers, parents, or mentors, they also serve as examples.

Jane Jacobs (1916-2006) American-Canadian journalist, author, urban theorist, activist

Dark Age Ahead, ch. 1 “The Hazard” (2004)

(Source)

Just as eating contrary to the inclination is injurious to the health, study without desire spoils the memory, and it retains nothing that it takes in.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Italian artist, engineer, scientist, polymath

MS. 2038, Bib. Nat. 34 r. [tr. McCurdy (1908)]

(Source)

Children learn what they experience. They are like wet cement. Any word that falls on them makes an impact.

Haim Ginott (1922-1973) Israeli-American school teacher, child psychologist, psychotherapist [b. Haim Ginzburg]

Between Parent and Child: Revised and Updated Edition, ch. 10 “Summing Up” (2003 ed.) [with A. Ginott and H. W. Goddard]

(Source)

Frequently paraphrased (e.g.) as "Children are like wet cement. Whatever falls on them makes an impression."

This is usually cited as being from the original 1965 edition of the book, but cannot be found there. Instead, it appears to be from the 2003 edition, as revised and updated by his wife, Dr Alice Ginott, and Dr H Wallace Goddard. It is unclear if Haim Ginott may have used this phrase in other contexts.

Why is it that we remember with effort but forget without effort? That we learn with effort but stay ignorant without effort? That we are active with effort, and lazy without effort?

[Quid est enim, quod cum labore meminimus, sine labore obliuiscimur; cum labore discimus, sine labore nescimus; cum labore strenui, sine labore inertes sumus?]Augustine of Hippo (354-430) Christian church father, philosopher, saint [b. Aurelius Augustinus]

City of God [De Civitate Dei], Book 22, ch. 22 (22.22) (AD 412-416) [tr. Green (Loeb) (1972)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:What is our labour to remember things, our labour to learn, and our ignorance without this labour? our agility got by toil, and our dullness if we neglect it?

[tr. Healey (1610)]For why is it that we remember with difficulty, and without difficulty forget? learn with difficulty, and without difficulty remain ignorant? are diligent with difficulty, and without difficulty are indolent?

[tr. Dods (1871)]How difficult it is to remember, how easy to forget; how hard to learn and how easy to be ignorant; how difficult to make an effort and how easy to be lazy.

[tr. Walsh/Honan (1954)]How is it that what we learn with toil we forget with ease? that it is hard to learn, but easy to be in ignorance? That activity goes against the grain, while indolence is second nature?

[tr. Bettenson (1972)]Why is it that we remember with such difficulty, but forget so easily? Why is it that we learn with such difficulty, yet so easily remain ignorant? Why is it that we are vigorous with such difficulty, yet so easily inert?

[tr. Dyson (1998)]

Shall I tell you the secret of the true scholar? It is this: Every man I meet is my master in some point, and in that I learn of him.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) American essayist, lecturer, poet

“Greatness,” Letters and Social Aims (1876)

(Source)

This appears to be the origin of the much more common paraphrase (not found in Emerson's works, but popularized by Dale Carnegie in How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936)): "In my walks, every man I meet is my superior in some way, and in that, I learn from him."

Thou art an heyre to fayre lyving, that is nothing, if thou be disherited of learning, for better were it to thee to inherite righteousnesse then riches, and far more seemely were it for thee to have thy Studie full of bookes, then thy pursse full of mony: to get goods is the benefit of Fortune, to keepe them the gift of Wisedome.

[Thou art an heir to fair living; that is nothing if thou be disinherited of learning, for better were it to thee to inherit righteousness than riches and far more seemly were it for thee to have thy study full of books than thy purse full of money. To get goods is the benefit of fortune, to keep them the gift of wisdom. (1916 ed.)]John Lyly (c. 1553-1606) was an English writer [also Lilly or Lylie]

Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit, “Letter to Alcius” (1579)

(Source)

Whence had you this illustrious name?

From virtue and unblemish’d fame.

By birth the name alone descends;

Your honour on yourself depends:

Think not your coronet can hide

Assuming ignorance and pride.

Learning by study must be won,

‘Twas ne’er entail’d from son to son.John Gay (1685-1732) English poet and playwright

“The Pack-Horse and Carrier (To a young Nobleman),” ll. 41-42

(Source)

Some printings of the poem leave off the prologue, of which this is a part.

Learning without thought ends in a blur. Thought without learning will soon totter.

[學而不思則罔、思而不學則殆。]Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 2, verse 15 (2.15) (6th C. BC – AD 3rd C.) [tr. Ware (1950)]

(Source)

Many (but not all) translators suggest that learning/study here is not general academics, but examining and maintaining the ancient traditions.

(Source (Chinese)). Alternate translations:Learning without thought is labour lost; thought without learning is perilous.

[tr. Legge (1861)]Learning with [sic] thought is a snare; thought without learning is a danger.

[tr. Jennings (1895)]Study without thinking is labour lost. Thinking without study is perilous.

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898)]Learning without thought is useless. Thought without learning is dangerous.

[tr. Soothill (1910)]Education without meditation is useless. Meditation without education is risky.

[tr. Soothill (1910), alternate]Research without thought is a mere net and entanglement: thought without gathering data, a peril.

[tr. Pound (1933)]He who learns but does not think, is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is in great danger.

[tr. Waley (1938)]If one learns from others but does not think, one will be bewildered. If, on the other hand, one thinks but does not learn from others, one will be in peril.

[tr. Lau (1979)]If one studies but does not think, one is caught in a trap. If one thinks but does not study, one is in peril.

[tr. Dawson (1993)]To study without thinking is futile. To think without studying is dangerous.

[tr. Leys (1997)]Learning without thinking is fruitless; thinking without learning is perplexing.

[tr. Huang (1997); additional translations.]Studying but not thinking, it is confused; Thinking but not studying, it is dangerous.

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998)]Learning without due reflection leads to perplexity; reflection without learning leads to perilous circumstances.

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]If he studies and does not reflect, he will be rigid. If he reflects but does not study, he will be shaky.

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998)]To learn and never think -- that's delusion. But to think and never learn -- that is perilous indeed!

[tr. Hinton (1998)]If you learn without thinking about what you have learned, you will be lost. If you think without learning, however, you will fall into danger.

[tr. Slingerland (2003)]Learning without thought is pointless. Thought without learning is dangerous.

[tr. Watson (2007)]If you learn but do not think, you will be dazed. If you think but do not learn, you will be in danger.

[tr. Chin (2014)]Learning from books without critical thinking results in confusion. Thinking vacuously without learning from books is perilous.

[tr. Li (2020)]

Take then good note of it. Nothing is too small. I counsel you, put down in record even your doubts and surmises. Hereafter it may be of interest to you to see how true you guess. We learn from failure, not from success!

Abraham "Bram" Stoker (1847-1912) Irish author, theater manager, journalist

Dracula, ch. 10, Dr. Seward’s Diary, 7 September [Abraham Van Helsing] (1897)

(Source)

Truth that has been merely learned is like an artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose; at best, like a nose made out of another’s flesh; it adheres to us only because it is put on. But truth acquired by thinking of our own is like a natural limb; it alone really belongs to us. This is the fundamental difference between the thinker and the mere man of learning.

[Hingegen klebt die bloß erlernte Wahrheit uns nur an, wie ein angeseßtes Glied, ein falscher Zahn, eine wächserne Nase, oder höchstens wie eine rhinoplastische aus fremdem Fleische. Die durch eigenes Denken erworbene Wahrheit aber gleicht dem natürlichen Gliede: fie allein gehört uns wirklich an. Darauf beruht der Unterschied zwischen dem Denker und dem bloßen Gelehrten.]Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) German philosopher

Parerga and Paralipomena, Vol. 2, ch. 22 “On Thinking for Oneself [Selbstdenken],” § 260 (1851) [tr. Saunders (1890)]

(Source)

Source (German). Alternate translations:Truth that has been merely learned adheres to us like an artificial limb, a false tooth, a waxen nose, or at best like one made out of another's flesh; truth which is acquired by thinking for oneself is like a natural member: it alone really belongs to us. Here we touch upon the difference between the thinking man and the mere man of learning.

[tr. Dircks (1897)]Truth that has merely been learnt adheres to us only as an artificial limb, a false tooth, a was nose does, or at most like transplanted skin; but a truth won by thinking for ourself is like a natural limb: it alone really belongs to us. This is what determines the difference between a thinker and a mere scholar.

[tr. Hollingdale (1970)]... other hand, the truth acquired through our own thinking is like the natural limb; it alone really belongs to us. On this rests the distinction between the thinker and the mere scholar.

[tr. Payne (1974)]

Real education precisely consists in the fact that we see beyond the symbols and the mere machinery of the age in which we find ourselves: education precisely consists in the realization of a permanent simplicity that abides behind all civilizations, the life that is more than meat, the body that is more than raiment. The only object of education is to make us ignore mere schemes of education. Without education, we are in a horrible and deadly danger of taking educated people seriously.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) English journalist and writer

“Our Note Book,” The Illustrated London News (1905-12-02)

(Source)

A successful man is simply one who doesn’t make a fool of himself in the same way more than two or three times running.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

A Little Book in C Major, ch. 3, § 5 (1916)

(Source)

I don’t think there is anything I have done that I wish I hadn’t done. Because I learn from everything I do. I’m in school every day. My diploma will be my tombstone.

Eartha Kitt (1927-2008) American singer and actress

In Lon Tuck, “It’s Been a Long Time But … Eartha’s Back!” Washington Post (1978-01-19)

(Source)

When a citation is given to this quotation, it's usually "Playbill 1978." It does indeed show up in an (unknown month) of Playbill Magazine in 1978, also in association with her starring role in the stage show Timbuktu, which opened on Broadway March 1st of that year, but this article appears to be the source. (see comments for the helpful tip).

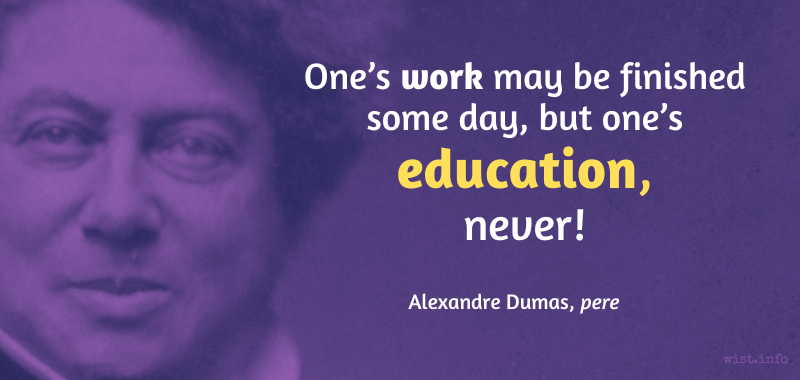

One’s work may be finished some day, but one’s education, never!

[L’oeuvre est terminée un jour; l’éducation jamais!]

Alexandre Dumas, père (1802-1870) French novelist and dramatist

My Memoirs [Mes Mémoires], ch. 113 (1852-1856) [tr. Waller (1907); 1826-1830: Vol. 3, Book 2, ch. 10]

(Source)

I am still learning.

[Ancora imparo.]

Michelangelo (1475-1564) Italian artist, architect, poet [Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni]

(Attributed)

Also rendered Anchora imparo. This is often described as a daily mantra of Michelangelo's. This association can be traced to Richard Duppa, The Lives and Works of Michael Angelo and Raphael (1806) [tr. Hazlitt]. Duppa misattributed to Michelangelo a drawing by Domenico Giuntalodi, which included the saying. The phrase itself was popular during the 16th Century.

While there's no indication that Michelangelo did not say this, or agree with the sentiment, it does not seem to have been solidly cited to him, or shown to be a personal motto, let alone being original to him.

More discussion: Michelangelo - Wikiquote.

What had men thought? What had men believed? How did they come by those thoughts and beliefs? How had men learned to govern themselves? Were the processes the same everywhere?

Did man build cities because of an inner drive, like that of a beaver to build dams? How much of what we do is free will, and how much is programmed in our genes? Why is each people so narrow that it believes that it, and it alone, has all the answers? In religion, is there but one road to salvation? Or are there many, all equally good, all going in the same general direction?

I have read my books by many lights, hoarding their beauty, their wit or wisdom against the dark days when I would have no book, nor a place to read.

I have known hunger of the belly kind many times over, but I have known a worse hunger: the need to know and to learn.

Louis L'Amour (1908-1988) American writer

Education of a Wandering Man: A Memoir, ch. 11 (1989)

(Source)

Nothing reveals more clearly men’s attitude to learning and literature, and what use they think these are to the State, than the low price they put on them, and their opinion of those who have chosen to practice them.

[Rien ne découvre mieux dans quelle disposition sont les hommes à l’égard des sciences et des belles-lettres, et de quelle utilité ils les croient dans la république, que le prix qu’ils y ont mis, et l’idée qu’ils se forment de ceux qui ont pris le parti de les cultiver.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 12 “Of Opinions [Des Jugements],” § 17 (12.17) (1688) [tr. Stewart (1970)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Nothing discovers better what disposition men have to Knowledge and Learning, and how profitable they are esteem'd to the Publick, than the price which is set on them, and the Idea they have formed of those who have taken the pains to improve them.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]Nothing discovers better what regard Men have to Science and polite Learning, and how profitable they esteem them to the Publick, than the price they set on them, and the Idea they form to themselves of those who have taken the pains to cultivate them.

[Curll ed. (1713)]Nothing better manifests the Regard paid to the Sciences and Literature, and Men's Sense of their Utility to the Public, than the Recompences assigned to them, and the Repute in which they stand who excel in them.

[Browne ed. (1752)]Nothing better demonstrates how men regard science and literature, and of what use they are considered in the State, than the recompense assigned to them, and the idea generally entertained of those persons who resolve to cultivate them.

[tr. Van Laun (1885)]

The day you stop learning is the day you begin decaying, and then you are no longer a human being.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

Commencement speech, Connecticut College (1975-05-25)

(Source)

Quoted in Peter Smith, ed., Onward! 25 Years of Advice, Exhortation, and Inspiration from America's Best Commencement Speeches (2000).

Every failure teaches a man something. For example, that he will probably fail again next time.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) American writer and journalist [Henry Lewis Mencken]

A Little Book in C Major, ch. 2, § 24 (1916)

(Source)

Variants:EXPERIENCE. A series of failures. Every failure teaches a man something, to wit, that he will probably fail again next time.

A Book of Burlesques, "The Jazz Webster" (1924)Every failure teaches a man something, to wit, that he will probably fail again next time.

Chrestomathy, ch. 30 "Sententiae" (1949)

With just enough of learning to misquote.

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824) English poet

“English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,” l. 66ff (1809)

(Source)

A real education takes place, not in the lecture hall or library, but in the rooms of friends, with earnest frolic and happy disputation. Wine can be a wiser teacher than ink, and banter is often better than books. That was my theory at least, and I was living by it.

Stephen Fry (b. 1957) British actor, writer, comedian

The Fry Chronicles: An Autobiography, Part 1 “College to Colleague” (2012)

(Source)

Let the writer take up surgery or bricklaying if he is interested in technique. There is no mechanical way to get the writing done, no shortcut. The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory. Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error.

William Faulkner (1897-1962) American novelist

“The Art of Fiction,” Interview by Jean Stein, Paris Review #12 (Spring 1956)

(Source)

Adept Kung said: “I do nothing to others that I wouldn’t want done to me.”

“That’s something you haven’t quite mastered, Kung,” the Master replied.

[子貢曰、我不欲人之加諸我也、吾亦欲無加諸人。

子曰、賜也、非爾所及也。]Confucius (c. 551- c. 479 BC) Chinese philosopher, sage, politician [孔夫子 (Kǒng Fūzǐ, K'ung Fu-tzu, K'ung Fu Tse), 孔子 (Kǒngzǐ, Chungni), 孔丘 (Kǒng Qiū, K'ung Ch'iu)]

The Analects [論語, 论语, Lúnyǔ], Book 5, verse 12 (5.12) (6th C. BC – AD 3rd C.) [tr. Hinton (1998)]

(Source)

The earliest appearance of the "Golden Rule" in world literature. See also 12.2, 15.24, and Matthew 7:12.

Originally numbered 5.11 by Legge and other early sources, as noted.

(Source (Chinese)). Alternate translations:Tsze-kung said, "What I do not wish men to do to me, I also wish not to do to men."

The Master said, "Ts'ze, you have not attained to that."

[tr. Legge (1861), 5.11]Tsz-kung made the remark: ‘That which I do not wish others to put upon me, I also wish not to put upon others.’

‘Nay,’ said the Master, 'you have not got so far as that.’

[tr. Jennings (1895), 5.11]A disciple said to Confucius, "What I do not wish that others should not do unto me, I also do not wish that I should do unto them."

"My friend," answered Confucius, "You have not yet attained to that."

[tr. Ku Hung-Ming (1898), 5.11]Tzŭ Kung said, "What I do not wish others to do to me, that also I wish not to do to them."

"Tzŭ!" observed the Master, "that is a point to which you have not attained."

[tr. Soothill (1910), 5.11]Tze-Kung said: What I don't want done to me, 1 don’t want to do to anyone else.

Confucius said: No, Ts'ze. you haven't got that far yet.

[tr. Pound (1933), 5.11]Tzu-kung said, What I do not want others to do to me, I have no desire to do to others.

The Master said, Oh Ssu! You have not quite got to that point yet.

[tr. Waley (1938), 5.11]Tuan-mu Tz'u said, "What I do not wish others to do unto me I also wish not to do unto others."

"You're not up to that!"

[tr. Ware (1950)]Tzu-kung said, "While I do not wish others to impose on me, I also wish not to impose on others."

The Master said, "Ssu, that is quite beyond you."

[tr. Lau (1979)]Zigong said: "If I do not want others to inflict something on me, I also want to avoid inflicting it on others."

The Master said: "Si, this is not a point you have yet reached."

[tr. Dawson (1993)]Zigong said: "I would not want to do to others what I do not want them to do to me."

The Master said: "Oh, you have not come that far yet!"

[tr. Leys (1997)]Zi-gong said: "What I do not wish others to impose on me, I also do not wish to impose on others."

The Master said: "Ci, this is beyond your reach."

[tr. Huang (1997)]Zigong said: "I do not want others to force anything on me, and I do not want to force anything on others, too."

Confucius said: "Si, it could not be reached by you."

[tr. Cai/Yu (1998), #104]Dž-gùng said, If I do not wish others to do something to me, I wish not to do it to them.

The Master said, Sz', this is not what you can come up to.

[tr. Brooks/Brooks (1998)]>Zigong said, "I do not want others to impose on me, nor do I want to impose on them."

Confucius replied, "Zigong, this is quite beyond your reach."

[tr. Ames/Rosemont (1998)]Zigong said, “What I do not wish others to do unto me, I also wish not to do unto others.”

The Master said, “Ah, Zigong! That is something quite beyond you.”

[tr. Slingerland (2003)]Zigong said, What I don’t want others to do to me, I want to avoid doing to others.

The Master said, Si (Zigong), you haven’t gotten to that stage yet.

[tr. Watson (2007)]Zigong said, "I do not wish others to impose what is unreasonable [jia] on me, and I do also not wish to impose what is unreasonable on others."

The Master said, "Si [Zigong], this is not something that is within your power."

[tr. Chin (2014)]Zi Gong said, "I hope other people will not impose on me against my will. Likewise, I will not impose on other people against their will too."

Confucius said, "Ci, you may not be able to do so all the time."

[tr. Li (2020)]

Usually one’s cooking is better than one thinks it is. And if the food is truly vile, as my ersatz eggs Florentine surely were, then the cook must simply grit her teeth and bear it with a smile — and learn from her mistakes.

Julia Child (1912-2004) American chef and writer

My Life In France, “Le Cordon Bleu,” sec. 2 (2006)

(Source)

Learn a little of anything, and you’re ready to proselytize.

Mignon McLaughlin (1913-1983) American journalist and author

The Neurotic’s Notebook, ch. 7 (1963)

(Source)

The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.

[Η αρχή της σοφίας είναι ο καθορισμός των όρων]

Socrates (c.470-399 BC) Greek philosopher

(Paraphrase)

Frequently attributed to Socrates (or, our source for most Socratic material, Plato), but not found as such in their works.

That said, there are places where Socrates indicates that searching out the meanings of ambiguities is important, and his "Socratic method" often involves calling definitions (or their implications) into question.

For example, in Phaedrus, 256d [tr. Jowett (1892)], Plato has Socrates note:First, the comprehension of scattered particulars in one idea; as in our definition of love, which whether true or false certainly gave clearness and consistency to the discourse, the speaker should define his several notions and so make his meaning clear.

[εἰς μίαν τε ἰδέαν συνορῶντα ἄγειν τὰ πολλαχῇ διεσπαρμένα, ἵνα ἕκαστον ὁριζόμενος δῆλον ποιῇ περὶ οὗ ἂν ἀεὶ διδάσκειν ἐθέλῃ. ὥσπερ τὰ νυνδὴ περὶ Ἔρωτος -- ὃ ἔστιν ὁρισθέν -- εἴτ᾽ εὖ εἴτε κακῶς ἐλέχθη, τὸ γοῦν σαφὲς καὶ τὸ αὐτὸ αὑτῷ ὁμολογούμενον διὰ ταῦτα ἔσχεν εἰπεῖν ὁ λόγος.]

Possibly from this sentiment, Socrates' student Antisthenes said the very similar to the subject quotation, As recorded in Arrianus, The Discourses of Epictetus [Epictetus Diatibai], Book 1, ch. 17 [tr. Long (1877)]:The beginning of education is the examination of terms.

[ἀρχὴ παιδεύσεως ἡ τῶν ὀνομάτων ἐπίσκεψις]

Arrianus was a student of Epictetus, who had been a pupil of Antisthenes. In the full passage, Epictetus ties this phrase back to Antisthenes and Socrates, possibly establishing the phrasing as a something directly said by Socrates.

More discussion of this quotation:

You are the sun who heals all clouded sight.

Solving my doubts, you bring me such content

That doubt, no less than knowing, is delight.[O sol che sani ogne vista turbata,

tu mi contenti sì quando tu solvi,

che, non men che saver, dubbiar m’aggrata.]Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) Italian poet

The Divine Comedy [Divina Commedia], Book 1 “Inferno,” Canto 11, l. 91ff (11.91-93) [Dante] (1309) [tr. Kirkpatrick (2006)]

(Source)

Flattering Virgil before he asks another question. (Source (Italian)). Alternate translations:O you, who like the Sun each weaken'd sight

Relieve, and give such pleasure when you clear

My doubts, that I to raise them oft desire.

[tr. Rogers (1782), l. 89ff]Can I repent my doubts! illumin'd Bard,

When thus thy heav'nly words my doubts reward?

[tr. Boyd (1802), st. 14]O Sun! who healest all imperfect sight,

Thou so content’st me, when thou solv’st my doubt,

That ignorance not less than knowledge charms.

[tr. Cary (1814)]O Sun, that healest every troubled sight!

So full content, thou solving, doth ensue,

Glads me no less to doubt, than judge aright.

[tr. Dayman (1843)]O Sun! who healest all troubled vision, thou makest so glad when thou resolvest me, that to doubt is not less grateful than to know.

[tr. Carlyle (1849)]Thou sun, that clearest every clouded sight,

You so content me to dissolve the knot,

To know is scarce so pleasing as to doubt.

[tr. Bannerman (1850)]Oh, sun! thou healer of the troubled sight,

What thou declarest makes me so content,

That as in knowledge I rejoice in doubt.

[tr. Johnston (1867)]O Sun, that healest all distempered vision,

Thou dost content me so, when thou resolvest,

That doubting pleases me no less than knowing!

[tr. Longfellow (1867)]O Sun that healest every troubled sight, so dost thou content me when thou solvest, that doubting gives me no less pleasure than knowing.

[tr. Butler (1885)]O Sun, that healest every troubled sight.

Thou so contentest me when thou mak'st clear

Doubts, that no less than knowledge they delight.

[tr. Minchin (1885)]O Sun that healest every troubled vision, thou dost content me so, when thou explainest, that doubt, not less than knowledge, pleaseth me.

[tr. Norton (1892)]O sun, that bringest healing unto all clouded vision, thou grantest unto me such satisfaction in thine unravelling, that doubting doth delight me.

[tr. Sullivan (1893)]Oh! sun, who makest whole all troubled vision.

Thou dost content me so when thou resolvest

That doubt is joy to me, no less than knowledge.

[tr. Griffith (1908)]O Sun that healest all troubled sight, so dost thou satisfy me with the resolving of my doubts that it is no less grateful to me to question than to know.

[tr. Sinclair (1939)]O Sun, who heal'st all troubled vision, and so

Contentest me where thou doest certify,

That to doubt pleaseth not less than to know ....

[tr. Binyon (1943)]O Sun that healest all dim sight, thou so

Doest charm me in resolving of my doubt,

To be perplexed is pleasant as to know.

[tr. Sayers (1949)]O sun which clears all mists from troubled sight,

such joy attends your rising that I feel

as grateful to the dark as to the light.

[tr. Ciardi (1954)]O sun that heal every troubled vision, you do content me so, when you solve, that questioning, no less than knowing, pleases me.

[tr. Singleton (1970)]O sun that shines to clear a misty vision,

such joy is mine when you resolve my doubts

that doubting pleases me no less than knowing!

[tr. Musa (1971)]O sun that heals all sight that is perplexed,

when I ask you, your answer so contents

that doubting pleases me as much as knowing.

[tr. Mandelbaum (1980)]O sun who clears every obscure perception

You give such satisfaction when you enlighten me

That, not less than knowledge, doubt is agreeable.

[tr. Sisson (1981)]O sun, that makes all troubled vision clear,

You give solutions I am so contented with

That asking, no less than knowing, pleases me.

[tr. Pinsky (1994), l. 87ff]O sun that heals every clouded sight, you content me so when you resolve questions, that doubting is no less pleasurable than knowing.

[tr. Durling (1996)]O Sun, that heals all troubled sight, you make me so content when you explain to me, that to question is as delightful as to know.

[tr. Kline (2002)]O sun, you who heal all troubled sight,

you so content me by resolving doubts

it pleases me no less to question than to know.

[tr. Hollander/Hollander (2007)]O shining sun, healer of troubled vision,

I'm satisfied so well, my mind so settled,

That knowledge pleases me no more than asking questions!

[tr. Raffel (2010)]"Bright sun," I said, you calm these doubts of mine

As you heal any troubled sight. Such ease

You bring me that to question pleases me

Like being answered."

[tr. James (2013)]

Profound ignorance makes a man dogmatical; he who knows nothing thinks he can teach others what he just now has learned himself.

[C’est la profonde ignorance qui inspire le ton dogmatique. Celui qui ne sait rien croit enseigner aux autres ce qu’il vient d’apprendre lui-même.]

Jean de La Bruyère (1645-1696) French essayist, moralist

The Characters [Les Caractères], ch. 5 “Of Society and Conversation [De la Société et de la Conversation],” § 76 (5.76) (1688) [tr. Van Laun (1885)]

(Source)

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Profound Ignorance makes a Man dogmatick. If he knows nothing, he thinks he can teach others what he is to learn himself.

[Bullord ed. (1696)]Profound Ignorance makes a Man dogmatick; he who knows nothing, thinks he can teach others what he just now has learn'd himself.

[Curll ed. (1713)]A dogmatic tone is generally inspired by abysmal ignorance. The man who knows nothing thinks he is informing others of something which he has that moment learnt.

[tr. Stewart (1970)]

Most people learn nothing from experience, except confirmation of their prejudices.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) English mathematician and philosopher

“The Lessons of Experience,” New York American (1931-09-23)

(Source)

In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned usually find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.

Eric Hoffer (1902-1983) American writer, philosopher, longshoreman

Reflections on the Human Condition, ch. 1, § 32 (1973)

(Source)

For a liberal arts education is not a tool like a hoe or a blueprint or an electric mixer. It is a true and precious stone which can glow just as wholesomely on a kitchen table as when it is put on exhibition in a jeweler’s window or bartered for bread and butter. Learning is a boon, a personal good. It is a light in the mind, a pleasure for the spirit, an object to be enjoyed. It is refreshment, warmth, illumination, a window from which we get a view of the world. To what barbarian plane are we descending when we demand that it serve only the economy?

Phyllis McGinley (1905-1978) American author, poet

“A Jewel in the Pocket,” Sixpence in Her Shoe (1964)

(Source)

The greatest of sages can commit one mistake, but not two; he may fall into error, but he doesn’t lie down and make his home there.

[En un descuido puede caer el mayor sabio, pero en dos no; y de paso, que no de asiento.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 214 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:The wisest man may very well fail once, but not twice; transiently, and by inadvertency, but not deliberately.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]A wise man may make one slip but never two, and that only in running, not while standing still.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]The wisest of men may slip once, but not twice, and that only by chance, and not by design.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

There’s a reason narcissists don’t learn from mistakes and that’s because they never get past the first step, which is admitting that they made one.

Robert Hogan (b. 1937) American psychologist

In Jeffrey Kluger, The Narcissist Next Door, ch. 6 (2014)

(Source)

Well, that’s Philosophy I’ve read,

And Law and Medicine, and I fear

Theology, too, from A to Zed;

Hard studies all, that have cost me dear.

And so I sit, poor silly man

No wiser now than when I began.[Habe nun, ach! Philosophie,

Juristerei und Medizin,

Und leider auch Theologie

Durchaus studiert, mit heißem Bemühn.

Da steh ich nun, ich armer Tor!

Und bin so klug als wie zuvor.]Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) German poet, statesman, scientist

Faust: a Tragedy [eine Tragödie], Part 1, sc. 4 “Night,” ll. 354ff (1808-1829) [tr. Luke (1987)]

(Source)

Some translations (and this site) include the Declaration, Prelude on the Stage, and Prologue in Heaven as individual scenes; others do not, leading to their Part 1 scenes being numbered three lower.

(Source (German)). Alternate translations:I've studied now Philosophy

And Jurisprudence, Medicine,

And even, alas! Theology

All through and through with ardour keen!

Here now I stand, poor fool, and see

I'm just as wise as formerly.

[tr. Priest (1808)]Now I have toil'd thro' all; philosophy,

Law, physic, and theology: alas!

All, all I have explor'd; and here I am

A weak blind fool at last: in wisdom risen

No higher than before.

[tr. Coleridge (1821)]I have now, alas, by zealous exertion, thoroughly mastered philosophy, the jurist's craft, and medicine -- and to my sorrow, theology too. Here I stand, poor fool that I am, just as wise as before.

[tr. Hayward (1831)]I have, alas! Philosophy,

Medicine, Jurisprudence too,

And to my cost Theology,

With ardent labour, studied through.

And here I stand, with all my lore,

Poor fool, no wiser than before.

[tr. Swanwick (1850)]Have now, alas! quite studied through

Philosophy and Medicine,

And Law, and ah! Theology, too,

With hot desire the truth to win!

And here, at last, I stand, poor fool!

As wise as when I entered school

[tr. Brooks (1868)]I've studied now Philosophy

And Jurisprudence, Medicine, --

And even, alas! Theology, --

From end to end, with labor keen;

And here, poor fool! with all my lore

I stand, no wiser than before:

[tr. Taylor (1870)]There now, I’ve toiled my way quite through

Law, Medicine, and Philosophy,

And, to my sorrow, also thee,

Theology, with much ado;

And here I stand, poor human fool,

As wise as when I went to school.

[tr. Blackie (1880)]I have studied, alas! Philosophy,

And Jurisprudence, and Medicine, too,

And saddest of all, Theology,

With arden labor, through and through!

And here I stick, as wise, poor fool,

As when my steps first turned to school.

[tr. Latham (1908)]I have, alas, studied philosophy,

Jurisprudence and medicine, too,

And, worst of all, theology

With keen endeavor, through and through --

And here I am, for all my lore,

The wretched fool I was before.

[tr. Kaufmann (1961)]Alas, I have studied philosophy,

the law as well as medicine,

and to my sorrow, theology;

studied them well with ardent zeal,

yet here I am, a wretched fool

no wiser than I was before.

[tr. Salm (1962)]I have pursued, alas, philosophy,

Jurisprudence, and medicine, And, help me God, theology,

With fervent zeal through thick and thin.

And here, poor fool, I stand once more,

No wiser than I was before.

[tr. Arndt (1976)]I've studied, alas, philosophy,

Law and medicine, recto and verso,

And how I regret it, theology also,

Oh God, how hard I've slaved away,

With what result? Poor foolish old man,

I'm not whit wiser than when I began!

[tr. Greenberg (1992)]Medicine, and Law, and Philosophy --

You've worked your way through every school,

Even, God help you, Theology,

And sweated at it like a fool.

Why labour at it any more?

You're no wiser now than you were before.

[tr. Williams (1999)]Ah! Now I’ve done Philosophy,

I’ve finished Law and Medicine,

And sadly even Theology:

Taken fierce pains, from end to end.

Now here I am, a fool for sure!

No wiser than I was before.

[tr. Kline (2003)]

Even when it comes to learning, the good student contradicts his teacher and makes him more eager to explain and defend the truth. Challenge someone discreetly and his teaching will be more perfect.

[Y aun para el aprender es treta del discípulo contradecir al maestro, que se empeña con más conato en la declaración y fundamento de la verdad; de suerte que la impugnación moderada da ocasión a la enseñanza cumplida.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 213 (1647) [tr. Maurer (1992)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:In matter of learning it is a cunning fetch in the Schollar to contradict his Master, inasmuch as it lays an obligation upon him, to labour to explain the truth with greater perspicuity and solidity.) So that moderate contradiction gives him that teaches occasion to teach thoroughly.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Also in learning it is a subtle plan of the pupil to contradict the master, who thereupon takes pains to explain the truth more thoroughly and with more force, so that a moderate contradiction produces complete instruction.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]A good trick on the party of the pupil is to bait his teacher, who thereby excites himself to greater effort in the declaration, and the foundations of this beliefs, whence it comes that well-moderated debate makes for most effective teaching.

[tr. Fischer (1937)]

We’re stronger because we’re democracies. We’re not afraid of free and fair elections, because true legitimacy can only come from one source — and that is the people. We’re not afraid of an independent judiciary, because no one is above the law. We’re not afraid of a free press or vibrant debate or a strong civil society, because leaders must be held accountable. We’re not afraid to let our young people go online to learn and discover and organize , because we know that countries are more successful when citizens are free to think for themselves.

Barack Obama (b. 1961) American politician, US President (2009-2017)

Speech, Nordea Concert Hall, Tallinn, Estonia (3 Sep 2014)

(Source)

You choose, you live the consequences. Every yes, no, maybe, creates the school you call your personal experience.

Progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning, then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; and in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive.

C. S. Lewis (1898-1963) English writer, literary scholar, lay theologian [Clive Staples Lewis]

Mere Christianity, Book 1, ch. 5 “We Have Cause to be Uneasy” (1952)

(Source)

Originally broadcast on BBC Radio (27 Aug 1941) under the title "What Can We Do About It?" Reprinted first in Broadcast Talks (1943) (US title The Case for Christianity (1944)).

I hope that in this year to come, you make mistakes.

Because if you are making mistakes, then you are making new things, trying new things, learning, living, pushing yourself, changing yourself, changing your world. You’re doing things you’ve never done before, and more importantly, you’re Doing Something.

So that’s my wish for you, and all of us, and my wish for myself. Make New Mistakes. Make glorious, amazing mistakes. Make mistakes nobody’s ever made before. Don’t freeze, don’t stop, don’t worry that it isn’t good enough, or it isn’t perfect, whatever it is: art, or love, or work or family or life.

Whatever it is you’re scared of doing, Do it.

Make your mistakes, next year and forever.Neil Gaiman (b. 1960) British author, screenwriter, fabulist

Blog entry (2011-12-31), “My New Year Wish”

(Source)

I do not approve the maxim which desires a man to know a little of everything. Superficial knowledge, knowledge without principles, is almost always useless and sometimes harmful knowledge.

Luc de Clapiers, Marquis de Vauvenargues (1715-1747) French moralist, essayist, soldier

Reflections and Maxims [Réflexions et maximes] (1746) [tr. Lee (1903)]

(Source)

Live with those from whom you can learn, — let friendly intercourse be a school for knowledge, and social contact, a school for culture; to make teachers of your friends is to join the need of learning to the joy of converse.

[Tratar con quien se pueda aprender. Sea el amigable trato escuela de erudición, y la conversación enseñanza culta; un hacer de los amigos maestros, penetrando el útil del aprender con el gusto del conversar.]

Baltasar Gracián y Morales (1601-1658) Spanish Jesuit priest, writer, philosopher

The Art of Worldly Wisdom [Oráculo Manual y Arte de Prudencia], § 11 (1647) [tr. Fischer (1937)]

(Source)

(Source (Spanish)). Alternate translations:Familiar Conversation ought to be the School of Learning and breeding. A man is to make his Masters of his Friends, seasoning the pleasure of conversing with the profit of instruction.

[Flesher ed. (1685)]Let friendly intercourse be a school of knowledge, and culture be taught through conversation; thus you make your friends your teachers and mingle the pleasures of conversation with the advantages of instruction.

[tr. Jacobs (1892)]Let friendly relations be a school of erudition, and conversation, refined teaching. Make your friends your teachers and blend the usefulness of learning with the pleasure of conversation.

[tr. Maurer (1992)]

“Darkness” is shorthand for anything that scares me — that I want no part of — either because I am sure that I do not have the resources to survive it or because I do not want to find out. The absence of God is in there, along with the fear of dementia and the loss of those nearest and dearest to me. So is the melting of polar ice caps, the suffering of children, and the nagging question of what it will feel like to die. If I had my way, I would eliminate everything from chronic back pain to the fear of the devil from my life and the lives of those I love — if I could just find the right night-lights to leave on.

At least I think I would. The problem is this: when, despite all my best efforts, the lights have gone off in my life (literally or figuratively, take your pick), plunging me into the kind of darkness that turns my knees to water, nonetheless I have not died. The monsters have not dragged me out of bed and taken me back to their lair. The witches have not turned me into a bat. Instead, I have learned things in the dark that I could never have learned in the light, things that have saved my life over and over again, so that there is really only one logical conclusion. I need darkness as much as I need light.

Barbara Brown Taylor (b. 1951) American minister, academic, author

Learning to Walk in the Dark, Introduction (2014)

(Source)

I believe that every human being with a physically normal brain can learn a great deal and can be surprisingly intellectual. I believe that what we badly need is social approval of learning and social rewards for learning. We can all be members of the intellectual elite and then, and only then, will a phrase like “America’s right to know” and, indeed, any true concept of democracy, have any meaning.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

“A Cult of Ignorance,” Newsweek (21 Jan 1980)

(Source)

All other knowledge is harmful to him who has not the knowledge of goodness.

[Toute autre science, est dommageable à celuy qui n’a la science de la bonté.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

Essays, Book 1, ch. 24 “Of Pedantry [Du pedantisme]” (c. 1572-78) (1.24) (1595) [tr. Ives (1925), ch. 25]

(Source)

While the original essay dates back to 1572-1578 and the first edition, this passage was added 1588–1592 for the 1595 edition.

(Source (French)). Alternate translations:Each other science is prejudciall unto him that hath not the science of goodnesse.

[tr. Florio (1603)]All other knowledge is detrimental to him who has not the science of becoming a good man.

[tr. Cotton (1686); Friswell (1868)]All other knowledge is hurtful to him who has not the science of goodness.

[tr. Cotton/Hazlitt (1877)]All other learning is hurtful to him who has not the knowledge of honesty and goodness.

[tr. Rector (1899)]Any other knowledge is harmful to a man who has not the knowledge of goodness.

[tr. Frame (1943), ch. 25]All other knowledge is harmful in a man who has no knowledge of what is good.

[tr. Screech (1987), ch. 25]

Self-education is, I firmly believe, the only kind of education there is. The only function of a school is to make self-education easier; failing that, it does nothing.

Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) Russian-American author, polymath, biochemist

Science Past, Science Future (1975)

(Source)

Learning and living. But they are really the same thing, aren’t they? There is no experience from which you can’t learn something. … And the purpose of life, after all, is to live it, to taste experience to the utmost, to reach out eagerly and without fear for newer and richer experience.

He [Napoleon III] was what I often think is a dangerous thing for a statesman to be — a student of history, and like most of those who study history, he learned from the mistakes of the past how to make new ones.

A. J. P. Taylor (1906-1990) British historian, journalist, broadcaster [Alan John Percivale Taylor]

“Mistaken Lessons from the Past,” The Listener (6 Jun 1963)

(Source)

No,

it’s no disgrace for a man, even a wise man,

to learn many things and not to be too rigid.

You’ve seen trees by a raging winter torrent,

how many sway with the flood and salvage every twig,

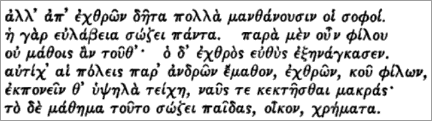

but not the stubborn — they’re ripped out, roots and all.[ἀλλ᾽ ἄνδρα, κεἴ τις ᾖ σοφός, τὸ μανθάνειν

πόλλ᾽, αἰσχρὸν οὐδὲν καὶ τὸ μὴ τείνειν ἄγαν.

ὁρᾷς παρὰ ῥείθροισι χειμάρροις ὅσα

δένδρων ὑπείκει, κλῶνας ὡς ἐκσῴζεται,

τὰ δ᾽ ἀντιτείνοντ᾽ αὐτόπρεμν᾽ ἀπόλλυται.]Sophocles (496-406 BC) Greek tragic playwright

Antigone, l. 710ff [Haemon] (441 BC) [tr. Fagles (1982), l. 794ff]

(Source)

Ancient Greek. Alternate translations:But that a man, how wise soe'er, should learn

In many things and slack his stubborn will,

This is no derogation. When the streams

Are swollen by mountain-torrents, thou hast seen

That all the trees wich bend them to the flood

Preserve their branches from the angry current,

While those which stem it perish root and branch.

[tr. Donaldson (1848)]The wisest man will let himself be swayed

By others' wisdom and relax in time.

See how the trees beside a stream in flood

Save, if they yield to force, each spray unharmed,

But by resisting perish root and branch.

[tr. Campbell (1873)]'Tis no disgrace even to the wise to learn

And lend an ear to reason. You may see

The plant that yields where torrent waters flow

Saves every little twig, when the stout tree

Is torn away and dies.

[tr. Storr (1859)]No, even when a man is wise, it brings him no shame to learn many things, and not to be too rigid. You see how the trees that stand beside the torrential streams created by a winter storm yield to it and save their branches, while the stiff and rigid perish root and all?

[tr. Jebb (1891)]True wisdom will be ever glad to learn,

And not too fond of power. Observe the trees,

That bend to wintry torrents, how their boughs

Unhurt remain; while those that brave the storm,

Uprooted torn, shall wither and decay.

[tr. Werner (1892)]No, though a man be wise, 'tis no shame for him to learn many things, and to bend in season. Seest thou, beside the wintry torrent's course, how the trees that yield to it save every twig, while the stiff-necked perish root and branch?

[tr. Jebb (1917)]It is not reason never to yield to reason!

In flood time you can see how some trees bend,

And because they bend, even their twigs are safe,

While stubborn trees are torn up, roots and all

[tr. Fitts/Fitzgerald (1939), l. 570ff]It is no weakness for the wisest man

To learn when he is wrong, know when to yield.

So, on the margin of a flooded river

Trees bending to the torrent live unbroken,

While those that strain against it are snapped off.

[tr. Watling (1947), l. 608ff]A man, though wise, should never be ashamed

of learning more, and must unbend his mind.

Have you not seen the trees beside the torrent,

the ones that bend them saving every leaf,

while the resistant perish root and branch?

[tr. Wyckoff (1954)]There's no disgrace, even if one is wise,

In learning more, and knowing when to yield.

See how the trees that grow beside a torrent

Preserve their branches, if they bend; the others,

Those that resist, are torn out, root and branch.

[tr. Kitto (1962)]But a wise man can learn a lot and never be ashamed;

He knows he does not have to be rigid and close-hauled.

You've seen trees tossed by a torrent in a flash flood:

If they bend, they're saved, and every twig survives,

But if they stiffen up, they're washed out from the roots.

[tr. Woodruff (2001)]But for a man, even if he is wise, to go on learning

many things and not to be drawn too taut is no shame.

You see how along streams swollen from winter floods

some trees yield and save their twigs,

but others resist and perish, root and branch.

[tr. Tyrell/Bennett (2002)]On the contrary, it is no shame for even a wise man to continue learning. Nor should a man be obstinate. One can see the trees on the heavy river-banks. Those that bend with the rushing current, survive, whereas those bent against it are torn, roots and all.

[tr. Theodoridis (2004)]For any man,

even if he’s wise, there’s nothing shameful

in learning many things, staying flexible.

You notice how in winter floods the trees

which bend before the storm preserve their twigs.

The ones who stand against it are destroyed,

root and branch.

[tr. Johnston (2005), l. 804ff]No, it's no disgrace for a man, even a wise man, to learn many things and not to be too rigid. You see how, in the winter storms, the trees yield that save even their twigs, but those who oppose it are destroyed root and branch.

[tr. Thomas (2005)]

Many much-learned men have no intelligence.

[Πολλοὶ πολυμαθέες νοῦν οὐκ ἔχουσιν.]

Democritus (c. 460 BC - c. 370 BC) Greek philosopher

Frag. 64 (Diels) [tr. Freeman (1948)]

(Source)

Diels citation "64. (190 N.) DEMOKRATES. 29."; collected in Joannes Stobaeus (Stobaios) Anthologium III, 4, 81. Freeman notes this as one of the Gnômae, from a collection called "Maxims of Democratês," but because Stobaeus quotes many of these as "Maxims of Democritus," they are generally attributed to the latter.

Alternate translations:

- "There are many who know many things, yet are lacking in wisdom." [tr. Bakewell (1907)]

- "Many who have learned much possess no sense." [tr. Barnes (1987)]

- "Many who have learned a lot do not have a mind." [tr. @sentantiq (2018)]

- "Many, though widely read, possess no sense." [Source]

Many who have not learned wisdom live wisely.

[Πολλοὶ λόγον μὴ μαθόντες ζῶσι κατὰ λόγον. ]

Democritus (c. 460 BC - c. 370 BC) Greek philosopher

Frag. 53 (Diels) [tr. Bakewell, 1907)]

(Source)

Diels citation "53. (122a N.) DEMOKRATES. 19.1."; collected in Joannes Stobaeus (Stobaios) Anthologium II, 15, 33. Often combined with fragment 53a. Bakewell lists this under "The Golden Sayings of Democritus." Freeman notes this as one of the Gnômae, from a collection called "Maxims of Democratês," but because Stobaeus quotes many of these as "Maxims of Democritus," they are generally attributed to the latter.

Alternate translations:

- "Many who have not learnt Reason, nevertheless live according to reason." [tr. Freeman (1948)].

- "Many live according to reason even if they have not learned it." [tr. @sentantiq (2020)]

- "Many do not learn reason but live in accordance with reason." [tr. Barnes (1987)]

For the man who rules efficiently must have obeyed others in the past, and the man who obeys dutifully appears fit at some later time to be a ruler.

[Nam et qui bene imperat, paruerit aliquando necesse est, et qui modeste paret, videtur qui aliquando imperet dignus esse.]

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Roman orator, statesman, philosopher

De Legibus [On the Laws], Book 3, ch. 2 / sec. 5 (3.2/3.5) [Marcus] (c. 51 BC) [tr. Keyes (1928)]

(Source)

(Source (Latin)). Alternate translations:For in order to command well, we should know how to submit; and he who submits with a good grace will some time become worthy of commanding.

[tr. Barham (1842)]For he who commands well, must at some time or other have obeyed; and he who obeys with modesty appears worthy of some day or other being allowed to command.

[tr. Barham/Yonge (1878)]A man who exercises power effectively will at some stage have to obey others, and one who quietly executes orders shows that he deserves, eventually, to wield power himself.

[tr. Rudd (1998)]For the good commander must necessarily at some time be obedient, and the person who is properly obedient seems like someone worthy at some time of commanding.

[tr. Zetzel (1999)]For it is necessary that he who commands well should obey at some time, and he who temperately obeys seems to be worthy of commanding at some time.

[tr. Fott (2013)]

The lesson of History is rarely learned by the actors themselves.

James A. Garfield (1831-1881) US President (1881), lawyer, lay preacher, educator

Letter to Professor Demmon (16 Dec 1871)

(Source)

He says, You have to study and learn so that you can make up your own mind about history and everything else but you can’t make up an empty mind. Stock your mind, stock your mind. It is your house of treasure and no one in the world can interfere with it. If you won the Irish Sweepstakes and bought a house that needed furniture would you fill it with bits and pieces of rubbish? Your mind is your house and if you fill it with rubbish from the cinemas it will rot in your head. You might be poor, your shoes might be broken, but your mind is a palace.

The essence of success is that it is never necessary to think of a new idea oneself. It is far better to wait until somebody else does it, and then to copy him in every detail, except his mistakes.

Aubrey Menen (1912-1989) British writer, novelist, satirist, theatre critic

The Abode of Love, Part 3, “The Random Wooings” (1956)

(Source)

Enter to grow in wisdom. / Depart to serve better thy country and thy kind.

Charles William Eliot (1834-1926) American academic

Lines inscribed on the 1890 (Dexter) Gate to Harvard Yard, Cambridge, Massachusetts

(Source)

On the front ("Enter") and back ("Depart") of the gate, which was erected in 1901 as a gift of the Harvard Class of 1890. Eliot also considered "Enter daily to grow in wisdom" and "Depart to serve better they country and mankind."

Paraphrases:

- "Enter to learn; go forth to serve."

- "Enter to learn; go forth to earn."

Each day grew older, and learnt something new.

Solon (c. 638 BC - 558 BC) Athenian statesman, lawmaker, poet

Quoted in Plutarch, “Solon,” Parallel Lives [tr. Dryden (1693); ed. Clough (1859)]

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

- "Old to grow, but ever learning." [tr. Stewart & Long (1881)]

- "I grow old in the pursuit of learning." [tr. Langhorne & Langhorne (1831)]

A learned fool is more foolish than an ignorant one.

[Un sot savant est sot plus qu’un sot ignorant.]

Molière (1622-1673) French playwright, actor [stage name for Jean-Baptiste Poquelin]

The Learned Ladies [Les Femmes Savantes], Act 4, sc. 3, l. 1296 [Clitandre] (1672)

(Source)

Alt. trans.:

A man may hear a thousand lectures, and read a thousand volumes, and be at the end of the process very much where he was, as regards knowledge. Something more than merely admitting it in a negative way into the mind is necessary, if it is to remain there. It must not be passively received, but actually and actively entered into, embraced, mastered. The mind must go half-way to meet what comes to it from without.

John Henry Newman (1801-1890) English prelate, Catholic Cardinal, theologian

The Idea of a University, Lecture 9 “Discipline of Mind,” sec. 4 (1852)

(Source)

Ah, it’s a lovely thing to know a thing or two.

[Ah, la belle chose que de savoir quelque chose.]

Molière (1622-1673) French playwright, actor [stage name for Jean-Baptiste Poquelin]

The Bourgeois Gentleman [Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme], Act 2, sc. 4 [M. Jourdain] (1670)

Title also translated as The Middle-Class Gentleman, The Tradesman turned Gentleman, The Middle-Class Aristocrat or The Would-Be Noble.

It is unclear where this highly common translation is from. Most identifiable sources are much more prosaic.

- "Ah! What a fine thing it is to know something!" [tr. Woolerey, Act 2, sc. 6; Jones; Page]

- "Ah, how wonderful it is to know something!" [tr. Applebaum (1998)]

- "How fine a thing it is but to know something!" [Source]

- "It's so reassuring to know something." [tr. Bermel (1987)]

- "Oh, what a beautiful thing it is to know something!" [tr. Pergolizzi (1999)]

- "It's wonderful to know so many things!" [tr. Rippon (2001), Act 1, sc. 3]

- Original French

EPOPS: You’re mistaken: men of sense often learn from their enemies. Prudence is the best safeguard. This principle cannot be learned from a friend, but an enemy extorts it immediately. It is from their foes, not their friends, that cities learn the lesson of building high walls and ships of war. And this lesson saves their children, their homes, and their properties.

CHORUS [LEADER]: It appears then that it will be better for us to hear what they have to say first; for one may learn something at times even from one’s enemies.

Aristophanes (c. 450-c. 388 BC) Athenian comedic playwright

The Birds, l. 375ff (414 BC) [tr. Anon. (1812), Ramage (1864)]

(Source)

Alt. trans. [Hickie (1853)]:

EPOPS: Yet, certainly, the wise learn many things from their enemies; for caution preserves all things. From a friend you could not learn this, but your foe immediately obliges you to learn it. For example, the states have learned from enemies, and not from friends, to build lofty walls, and to possess ships of war. And this lesson preserves children, house, and possessions.

CHORUS [LEADER]: It is useful, as it appears to me, to hear their arguments first; for one might learn some wisdom even from one's foes.

Alt. trans. [O'Neill (1938)]:

EPOPS: The wise can often profit by the lessons of a foe, for caution is the mother of safety. It is just such a thing as one will not learn from a friend and which an enemy compels you to know. To begin with, it's the foe and not the friend that taught cities to build high walls, to equip long vessels of war; and it's this knowledge that protects our children, our slaves and our wealth.

LEADER OF THE CHORUS: Well then, I agree, let us first hear them, for that is best; one can even learn something in an enemy's school.

The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those that cannot read or write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.

Alvin Toffler (1928-2016) American writer and futurist

(Paraphrase)

(Source)

Sometimes given as "The illiterate of the future ..." This ubiquitous (mis)quotation of Toffler is a conflation of two sentences in ch. 18 of Toffler's Future Shock (1970).

- On p. 414, Toffler writes, "By instructing students how to learn, unlearn and relearn, a powerful new dimension can be added to education."

- In the next paragraph, he quotes psychologist Herbert Gerjuoy: "Tomorrow's illiterate will not be the man who can't read; he will be the man who has not learned how to learn."

Success don’t konsist in never making blunders, but in never making the same one the seckond time.

[Success doesn’t consist in never making blunders, but in never making the same one the second time.]

A real writer learns from earlier writers the way a boy learns from an apple orchard — by stealing what he has a taste for and can carry off.

Archibald MacLeish (1892–1982) American poet, writer, statesman

In Charles Poore, “Mr. MacLeish and the Disenchantmentarians,” The New York Times (25 Jan 1968)

(Source)

Remember, too, that you have the right to make mistakes. Exercise it. Good judgment comes from experience, and often experience comes from bad judgment.

Rita Mae Brown (b. 1944) American author, playwright

Starting from Scratch, Part 4 (1988)

(Source)

Brown popularized the phrase, but it had been expressed before. More information: Good Judgment Depends Mostly on Experience and Experience Usually Comes from Poor Judgment – Quote Investigator.

Just as birds sometimes go in search of grain, carrying it in their beaks without tasting it to stuff it down the beaks of their young, so too do our schoolmasters go foraging for learning in their books and merely lodge it on the tip of their lips, only to spew it out and scatter it on the wind.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

The Complete Essays, I:25 “On Schoolmasters [Du pédantisme]”

(Source)

We readily inquire, “Does he know Greek or Latin?” “Can he write poetry and prose?” But what matters most is what we put last: “Has he become better and wiser?” We ought to find out not who understands most but who understands best.

[Nous nous enquerons volontiers: “Sçait-il du Gre ou du Latin? Estriil en vers ou en prose?” Mais sìl est devenu ou plus advisé, c’estoit le principal, et c’est ce qui demeure derrier. Il falloit sènquerir qui est mieux sçavant, non qui est plus sçavant.]

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

The Complete Essays, I:25 “On Schoolmasters [Du pédantisme]”

(Source)

As the true object of education is not to render the pupil the mere copy of his preceptor, it is rather to be rejoiced in, than lamented, that various reading should lead him into new trains of thinking.

William Godwin (1756-1836) English journalist, political philosopher, novelist

The Enquirer, Essay 15 “Of Choice in Reading” (1797)

(Source)

I gladly come back to the theme of the absurdity of our education: its end has not been to make us good and wise but learned. And it has succeeded. It has not taught us to seek virtue and to embrace wisdom: it has impressed upon us their derivation and their etymology. We know how to decline the Latin word for virtue: we do not know how to love virtue. Though we do not know what wisdom is in practice or from experience we do know the jargon off by heart.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) French essayist

The Complete Essays, II:17 “On Presumption” [tr. Screech (1987)]

(Source)

Books have led some to learning and others to madness, when they swallow more than they can digest.

Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374) Italian scholar and poet [a.k.a. Petrarch]

Remedies for Fortune Fair and Foul [De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae] [tr. Elton (1893)]

Alt. trans.: "Books have brought some men to knowledge, and some to madness. whilst they drew out of them more than they could digest." [tr. Dobson (1791)]

Alt. trans.: "Books have led some to knowledge and some to madness, who drew from them more than they could hold." [tr. Rawski (1991)]

Civilization is not inherited; it has to be learned and earned by each generation anew; if the transmission should be interrupted for one century, civilization would die, and we should be savages again.

William James (Will) Durant (1885-1981) American historian, teacher, philosopher

The Lessons of History, ch. 13 “Is Progress Real?” (1968) [with Ariel Durant]

(Source)

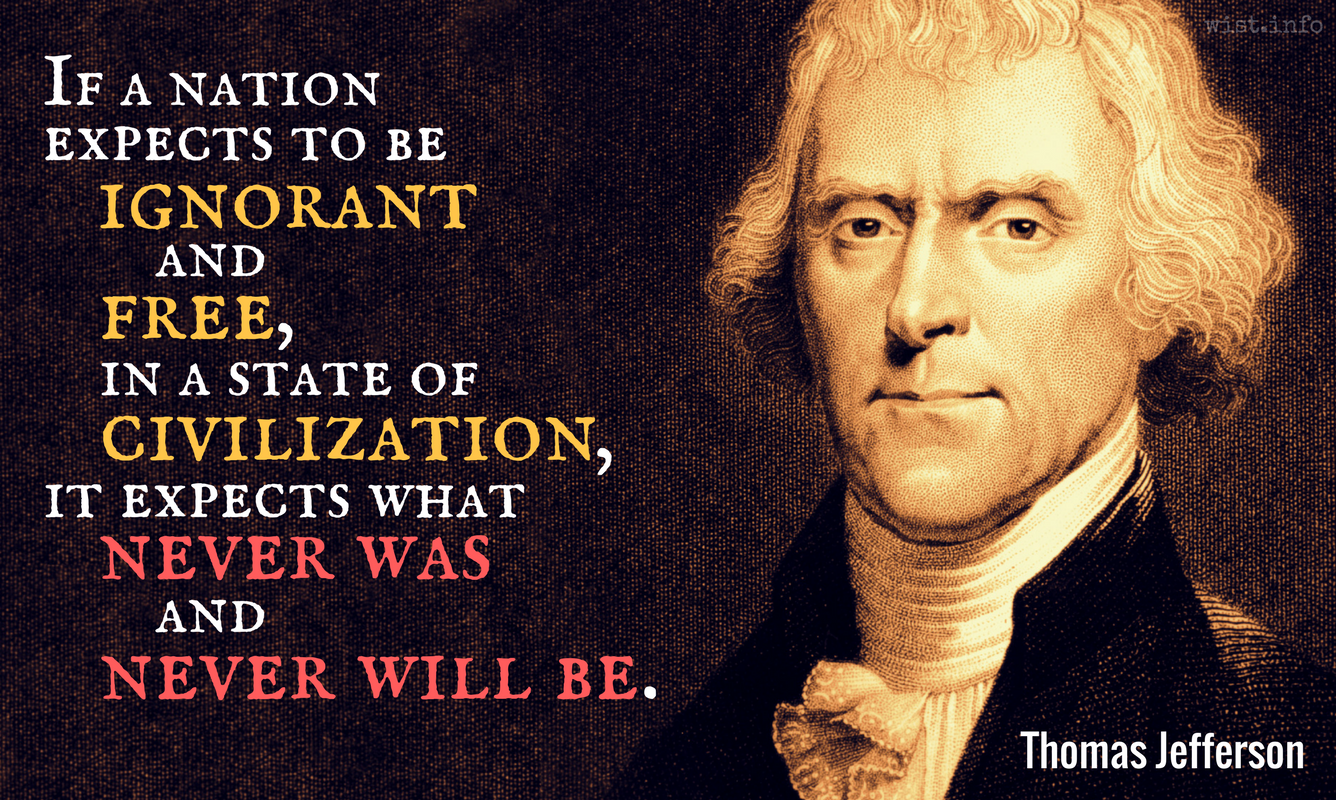

If a nation expects to be ignorant & free, in a state of civilisation, it expects what never was & never will be. The functionaries of every government have propensities to command at will the liberty & property of their constituents. there is no safe deposit for these but with the people themselves; nor can they be safe with them without information. Where the press is free and every man able to read, all is safe.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) American political philosopher, polymath, statesman, US President (1801-09)

Letter (1816-01-06) to Charles Yancey

(Source)

I am always for getting a boy forward in his learning; for that is a sure good. I would let him at first read any English book which happens to engage his attention; because you have done a great deal when you have brought him to have entertainment from a book. He’ll get better books afterwards.

From your parents you learn love and laughter and how to put one foot before the other. But when books are opened you discover you have wings.

We cannot blame the schools alone for that dismal decline in SAT verbal scores. […] What happens at home really matters. And when our kids come home from school, do they pick up a book, or do they sit glued to the tube watching music videos? Parents: don’t make the mistake of thinking your kids only learn from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. You are and always will be their first teachers.

George H. W. Bush (1924-2018) American politician, diplomat, US President (1989-1993)

Speech, Lewiston Comprehensive High School, Maine (3 Sep 1991)

(Source)

Often misattributed to his son, George W. Bush.

We can draw lessons from the past, but we cannot live in it.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-1973) American politician, educator, US President (1963-69)

Speech (1963-12-13), Consumer Advisory Council, Washington, D.C.

(Source)

If you live long enough, you’ll make mistakes. But if you learn from them, you’ll be a better person. It’s how you handle adversity, not how it affects you. The main thing is never quit, never quit, never quit.

“Men, Pencroft, however learned they may be, can never change anything of the cosmographical order established by God Himself.”

“And yet,” added Pencroft, “the world is very learned. What a big book, captain, might be made with all that is known!”

“And what a much bigger book still with all that is not known!” answered Harding.

[Les hommes, Pencroff, si savants qu’ils puissent être, ne pourront jamais changer quoi que ce soit à l’ordre cosmographique établi par Dieu même.

— Et pourtant, ajouta Pencroff, qui montra une certaine difficulté à se résigner, le monde est bien savant! Quel gros livre, monsieur Cyrus, on ferait avec tout ce qu’on sait!

— Et quel plus gros livre encore avec tout ce qu’on ne sait pas, répondit Cyrus Smith.]Jules Verne (1828-1905) French novelist, poet, playwright

The Mysterious Island, Part 3, ch. 14 (1874)

(Source)

But, on the other hand, Uncle Abner said that the person that had took a bull by the tail once had learnt sixty or seventy times as much as a person that hadn’t, and said a person that started in to carry a cat home by the tail was gitting knowledge that was always going to be useful to him, and warn’t ever going to grow dim or doubtful.

Mark Twain (1835-1910) American writer [pseud. of Samuel Clemens]

Tom Sawyer Abroad, ch. 10 (1894)

(Source)

Frequently misquoted as "A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way."